Читать книгу Targeted: My Inside Story of Cambridge Analytica and How Trump, Brexit and Facebook Broke Democracy - Brittany Kaiser - Страница 8

Оглавление1

A Late Lunch

EARLY 2014

The first time I saw Alexander Nix, it was through a thick pane of glass, which is perhaps the best way to view a man like him.

I had shown up late for a business lunch that had been hastily arranged by my close friend Chester Freeman, who was acting, as he often did, as my guardian angel. I was there to meet with three associates of Chester’s, two men I knew and one I didn’t, all of whom were looking for talent at the intersection of politics and social media. I counted this area as part of my political expertise, having worked on Obama’s 2008 campaign; though I was still busy researching my dissertation for my PhD, I was also on the market for a well-paying job. I had kept the fact secret from nearly everyone except Chester, but I was in urgent need of a stable source of income, to take care of myself and help out my family back in Chicago. This lunch was a way for me to obtain a potentially short-term and lucrative consultancy, and I was grateful to Chester for the well-timed assist.

By the time I arrived, however, lunch was nearly over. I’d had appointments that morning, and though I’d hustled to get there, I was late, and I found Chester and the two friends of his I already knew huddled together in the cold outside the Mayfair sushi restaurant, smoking post-meal cigarettes in view of the neighborhood’s Georgian mansions, stately hotels, and expensive shops. The two men were from a country in Central Asia, and like Chester, they, too, were passing through London on business. They had reached out to him for help in connecting with someone who could aid them with digital communications (email and social media campaigns) in an important upcoming election in their country. Though I knew neither of them well, both were powerful men I’d met before and liked, and by gathering us there for the lunch, Chester intended only to do all of us a favor.

Now, in welcome, he rolled me my own cigarette and leaned in to light it for me. Chester, his two friends, and I caught up with one another, chatting brightly and shielding ourselves from the rising wind. As Chester stood there in the afternoon light, ruddy cheeked and happy, I couldn’t help but be impressed by his journey. He’d recently been appointed as a diplomat for business and trade relations by the prime minister of a small island nation, but back when I’d first met him, at the Democratic National Convention in 2008, he’d been an idealistic, shaggy-haired nineteen-year-old wearing a blue dashiki. The convention had been in Denver that year, and Chester and I had both been standing in a long line outside Broncos Stadium, waiting to see Hillary Clinton endorse Barack Obama as the party’s nominee, when we bumped into each other and started talking.

We had come a long way since then, and each of us now had a hodgepodge of political experience under our proverbial belts. He and I had long shared the dream of “growing up” to do international political work and diplomacy, and recently he’d proudly sent me a picture of the certificate he received upon his diplomatic appointment. And while the Chester who now stood before me outside the restaurant looked the part of a newly minted diplomat, I still recognized him as the genius chatterbox friend I’d known from the beginning, as close to me as a brother.

As we smoked, Chester apologized to me for the last-minute, cobbled-together lunch. And by way of acknowledging what a motley crew he’d assembled there, he gestured to the plate glass window, through which I glimpsed the third person he’d invited—the man, still seated inside, who would change my life and, later, the world.

The fellow appeared to be an average, cut-from-the-cloth Mayfair business type, cell phone held tightly to his ear, but as Chester explained, he was not just any businessman. His name was Alexander Nix and he was the CEO of a British-based elections company. The company, Chester went on, was called the SCL Group, short for Strategic Communications Laboratories, which struck me as the sort of name a board of directors would give a glorified advertising firm it wanted to sound vaguely scientific. In point of fact, Chester said, SCL was a wildly successful company. Over a span of twenty-five years, it had procured defense contracts worldwide and run elections in countries across the globe. Its basic function, he said, was putting into power presidents and prime ministers and, in many cases, ensuring that they stayed there. Most recently, the SCL Group had been working on the reelection campaign of the prime minister for whom Chester now worked, which was how I presumed Chester had come to know this Nix character.

It took me a moment to digest it all. Chester’s intention in putting us all together that afternoon was certainly a tangle of potentially conflicting interests. I was there to pitch my services to the two friends, but it now seemed clear that the elections CEO was there to do so as well. And it occurred to me that in addition to my lateness, my youth and lack of experience no doubt meant that, instead, the CEO would likely already have secured the business I wished to have with Chester’s two friends.

I peered through the window at the man. I saw him now as someone more than average. With his phone still to his ear, he suddenly looked terribly serious and consummately professional. Clearly, I was outclassed and outdone. I was disappointed, but I tried hard not to let it show.

“I thought you might like to meet him,” Chester offered. “You know,” he went on, “he’s a good connection and all that,” meaning, perhaps, future paying work. “Or,” Chester suggested, alternatively, “at least interesting fodder for your dissertation.”

I nodded. He was probably right. As disappointed as I might be about what I presumed was already a lost business opportunity, I was academically curious. What did the CEO of such a company actually do? I’d never heard of an elections company.

From my time with Obama and from my recent volunteer work in London with the Democratic Party expat organization Democrats Abroad and with the super PAC Ready for Hillary, my own experience was that campaign managers ran campaigns, working in their own country with, of course, the support of a small but elite group of highly paid experts and an army of underpaid staff, volunteers, and unpaid interns, as I had been. After the 2008 Obama campaign, I’d certainly come across a few people who later became professional campaign consultants, such as David Axelrod, who had been chief strategist for Obama and had gone on to advise the British Labour Party; and Jim Messina, once called “the most powerful person in Washington that you haven’t heard of,”1 who had helmed Obama’s 2012 campaign, had become Obama’s White House chief of staff, and would go on to advise foreign leaders ranging from David Cameron to Theresa May. Still, it had never occurred to me that there existed entire companies dedicated to the goal of getting people elected to political office abroad.

I regarded the figure through the restaurant’s plate glass window with equal parts curiosity and puzzlement. Chester was right. I might not get any work at the moment, but maybe I would in the future. And I certainly could use the afternoon as research.

The restaurant was pleasant enough, brightly lit from above, with pale wooden floors and cream-colored walls along which Japanese artwork had been tidily hung. Approaching the table, I surveyed the man whom I had been watching from outside. He’d finished his phone call, and Chester made the introductions.

At closer range now, I could see that Nix wasn’t your typical Mayfair business type after all. He was what the British call “posh.” Immaculate and traditional, he was dressed in a dark, bespoke navy suit and a woven silk tie knotted at the neck of a starched button-down—pure Savile Row, right down to his shoes, which had been shined to a blinding polish. He had beside him a well-worn-in leather briefcase with an old-fashioned brass lock; it looked like it could have been his grandfather’s. Though I was a full-blooded American, I had lived in the United Kingdom ever since I graduated from high school, and I knew a member of the British upper crust when I saw one.

Alexander Nix, though, was what I’d call upper-upper crust. He was handsome in a British boarding school sort of way—Eton, as it turned out—and he was trim, with a sharp, arrow-like chin and the slightly bony build of someone who doesn’t spend any time at the gym. His eyes were a striking, opaque bright blue, and his complexion was smooth and unwrinkled, as though he’d never known a moment of worry in his life. In other words, it was the face of utter privilege. And as he stood before me in that West End London restaurant, I could easily have imagined him helmeted astride a galloping polo pony with a custom-made wooden mallet in hand.

I tried to guess his age. If he were as successful as Chester had claimed, he was likely older than I was by at least a decade, and his posture, equal parts upright and confident, yet somehow also relaxed, suggested an early middle-aged life, one that was aristocratic with a pinch of meritocracy thrown in. He looked as though he’d come into the world with a pretty good leg up, but that he’d used those legs, if Chester was right, in order to stand on his own two feet.

Nix greeted me warmly, as if I were an old friend, shaking my hand with vigor. As we took our seats at a large table tucked away from most of the others in the restaurant, he quickly, though not impolitely, turned his attention to Chester’s other two friends and effortlessly picked up the thread of what must have been the conversation they were having before I arrived.

With little revving up, Nix entered full-pitch mode. I recognized what that was because I knew how to do it myself. In order to support myself through all my studies, I’d taught myself how to pitch clients for consulting work, although I could see how skilled Nix was at it. I had neither half his charm nor his experience, and I certainly didn’t have his polish. His delivery was as bright as the shine on his expensive shoes.

I listened as he laid out the long history of the company for which he worked. The SCL Group had been established in 1993. Since then, it had run more than two hundred elections and had carried out defense, political, and humanitarian projects in some fifty countries worldwide; when Nix listed them, it sounded like the roster of countries on a United Nations subcommittee: Afghanistan, Colombia, India, Indonesia, Kenya, Latvia, Libya, Nigeria, Pakistan, the Philippines, Trinidad and Tobago, and more. Nix himself had been with SCL for eleven years at that point.

The sheer accumulation of experience and the volume of his work was astonishing to me, and humbling. I couldn’t help but note that I was six years old the year of SCL’s founding, and in the period of time when I was in kindergarten, grade school, and high school, Nix had been part of building a small but powerful empire. While next to those of my peers, my résumé looked pretty good—I’d done a great deal of international work while living abroad and since my time interning on the Obama campaign—but I couldn’t compete with Nix.

“So, we’re in America now,” Nix was saying, with barely contained enthusiasm.

Just recently, SCL had established a nascent presence there, and Nix’s short-term aim was to run as many of the upcoming American midterms in November 2014 as he could, and then go on and corner the elections business in the United States as a whole, including a presidential campaign if he could get his hands on it.

It was an audacious thing to say. But he had already secured the midterm campaigns of some notable candidates and causes. He’d signed the likes of a congressman from Arkansas by the name of Tom Cotton, a wunderkind Harvard grad and Iraq War veteran who was running for a seat in the Senate. He’d signed the entire slate of GOP candidates across all the races in the state of North Carolina. And he’d snagged the business of a powerful and deep-pocketed political action committee, or super PAC, belonging to UN ambassador John Bolton, a controversial figure on the right with whom I was all too familiar.

I had lived in the United Kingdom for years, but I knew at least some of the American neoconservative standouts such as Bolton. He was the kind of figure it was hard to ignore: a hawkish lightning rod who, along with a host of other neocons, had recently been revealed to be the brains and cash behind a shadowy organization called Groundswell, the intention of which, among other things, was to undermine the Obama presidency and hype the Hillary Clinton Benghazi controversy,2 the latter issue with which I was personally familiar. I had worked in Libya and had known Ambassador Christopher Stevens, who died there due in part to the poor decision making of the U.S. State Department, I thought.

I sat sipping my tea and took careful note of Nix’s list of clients. At a glance, they may have sounded like many other Republicans, but the politics of each was so profoundly the opposite of my own beliefs that they formed a veritable rogues’ gallery of nemeses to most of my heroes, such as Obama and Hillary. The people Nix named were, to my mind, political pariahs—or even better, piranhas, fish in whose pond I could never have imagined myself taking a safe swim.

Never mind that the special interest groups Nix was working for, with causes ranging from gun rights to pro-life advocacy, were anathema to me. For all my life, I had supported causes that leaned distinctly to the left.

Nix was thrilled with himself, with his company, and with the people and groups he’d managed to lasso. You could see it in his eyes. He was terribly busy, he said, so busy and so hopeful for the future that the SCL Group had had to spin off an entirely new company just to manage the work in the United States alone.

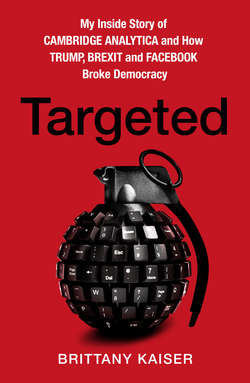

That new company was called Cambridge Analytica.

It had been in business for just under a year, but the world had best pay attention to it, Nix said. Cambridge Analytica was about to cause a revolution.

The revolution Nix had in mind had to do with Big Data and analytics.

In the digital age, data was “the new oil.” Data collection was an “arms race,” he said. Cambridge Analytica had amassed an arsenal of data on the American public of unprecedented size and scope, the largest, as far as he knew, anyone had ever assembled. The company’s monster databases held between two thousand and five thousand individual data points (pieces of personal information) on every individual in the United States over the age of eighteen. That amounted to some 240 million people.

Nix paused and looked at Chester’s friends and at me, as if to let the number sink in.

But merely having Big Data wasn’t the solution, he said. Knowing what to do with it was the key. That involved more scientific and precise ways of putting people into categories: “Democrat,” “environmentalist,” “optimist,” “activist,” and the like. And for years, the SCL Group, Cambridge Analytica’s parent company, had been identifying and sorting people using the most sophisticated method in behavioral psychology, which gave it the capability of turning what was otherwise just a mountain of information about the American populace into a gold mine.

Nix told us about his in-house army of data scientists and psychologists who had learned precisely how to know whom they wanted to message, what messaging to send them, and exactly where to reach them. He had hired the most brilliant data scientists in the world, people who could laser in on individuals wherever they were to be found (on their cell phones, computers, tablets, on television) and through any kind of medium you could imagine (from audio to social media), using “microtargeting.” Cambridge Analytica could isolate individuals and literally cause them to think, vote, and act differently from how they had before. It spent its clients’ money on communications that really worked, with measurable results, Nix said.

That, he said, is how Cambridge Analytica was going to win elections in America.

While Nix spoke, I glanced over at Chester, hoping to make eye contact in order to figure out what opinion he might have formed of Nix, but I wasn’t able to catch his attention. As for Chester’s friends, I could see from the looks on their faces that they were duly wowed as Nix went on about his American company.

Cambridge Analytica was filling an important niche in the market. It had been formed to meet pent-up, unmet demand. The Obama Democrats had dominated the digital communications space since 2007. The Republicans lagged sorely behind in technology innovation. After their crushing defeat in 2012, Cambridge Analytica had come along to level the playing field in a representative democracy by giving the Republicans the technology they lacked.

As for what Nix could do for Chester’s friends, whose country didn’t have Big Data, due to lack of internet penetration, SCL could get that started for them, and it could use social media to get their message out. Meanwhile, it could also do more traditional campaigning, everything from writing policy platforms and political manifestos to canvassing door-to-door to analyzing target audiences.

The men complimented Nix. I was well enough acquainted with the two by now, though, to see how his pitch had overwhelmed them. I knew their country hadn’t the infrastructure to carry out what Nix was planning to do in America, and his strategy didn’t sound particularly affordable, even to two men with reasonably deep pockets.

For my part, I was shocked at what Nix had shared—stunned, in fact. I’d never heard anything like it before. He’d described nothing less than using people’s personal information to influence them and, hence, to change economies and political systems around the world. He’d made it sound easy to sway voters to make irreversible decisions not against their will but, at the very least, against their usual judgment, and to change their habitual behavior.

At the same time, I admitted, if only to myself, that I was gobsmacked by his company’s capabilities. Since my first days in political campaigning, I had developed a special interest in the subject of Big Data analytics. I wasn’t a developer or a data scientist, but like other Millennials, I had been an early adopter of all sorts of technology and had lived a digital life from my earliest years. I was predisposed to see data as an integral part of my world, a given, at its worst benign and utilitarian, and at its best possibly transformative.

I myself had used data, even rudimentarily in elections. Aside from being an unpaid intern on Obama’s New Media team, I had volunteered for Howard Dean’s primary race four years earlier, and then both John Kerry’s presidential campaign, as well for both the DNC itself and Obama’s senatorial run. Even basic use of data to write emails to undecided voters on what they cared about was “revolutionary” at the time. Howard Dean’s campaign broke all existing fund-raising records by reaching people online for the first time.

My interest in data was coupled with my firsthand knowledge of revolutions. A lifelong bookworm, I’d been a student forever but had always engaged in the wider world. In fact, I had always felt that it was imperative for academics to find ways to spin the threads of the high-minded ideas they came up with in the ivory tower into cloth that was of real use to others.

Even though it involved a peaceful transfer of power, you could say that the Obama election was my first experience of a revolution. I had been a part of the spirited celebration in Chicago on the night Obama won his first presidential election, and that street party of millions felt like a political coup.

I’d also had the privilege, and had sometimes experienced the danger, of being on the ground in countries where revolutions were happening silently, had just broken out, or were about to. As an undergraduate, I studied for a year in Hong Kong, where I volunteered with activists shuttling refugees from North Korea via an underground railroad through China and out to safety. Immediately upon graduating from college, I spent time in parts of South Africa, where I worked on projects with former guerrilla strategists who’d helped overthrow apartheid. And in the aftermath of the Arab spring, I worked in post-Gaddafi Libya, and have continued to be interested and involved in independent diplomacy for that country for many years. I guess you could say I had the uncanny habit of putting myself in the middle of places during their most turbulent times.

I had also studied how data could be used for good, looking at how people empowered by it had used it to seek social justice, in some cases to expose corruption and bad actors. In 2011, I had written my master’s thesis using leaked government data from Wikileaks as my primary source material. The data showed what had happened during the Iraq War, exposing numerous cases of crimes against humanity.

From 2010 onward the “hacktivist” (i.e., activist hacker) Julian Assange, founder of the organization, had declared virtual war on those that had waged literal war on humanity by widely disseminating top secret and classified files that proved damning to the American government and the U.S. military. The data dump, called “The Iraq War Files,” prompted public discourse on protection of civil liberties and international human rights from abuses of power.

Now, as part of my PhD dissertation in diplomacy and human rights, and a continuation of my earlier work, I was going to combine my interest in Big Data with my experience of political turbulence, looking at how data could save lives. I was particularly interested in something called “preventive diplomacy.” The United Nations and nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) across the globe were looking for ways to use real-time data to prevent atrocities such as the genocide that occurred in Rwanda in 1994, where earlier action could have been taken if the data had been available to decision makers. “Preventive” data monitoring—of everything from the price of bread to the increased use of racial slurs on Twitter—could give peacekeeping organizations the information they needed to identify, monitor, and peacefully intervene in high-risk societies before conflicts escalated. The proper gathering and analysis of data could prevent human rights violations, war crimes, and even war itself.

Needless to say, I understood the implications of the capabilities Nix was alleging the SCL Group possessed. His talk of data, combined with his words about revolutions, left me unsettled about his intentions and the risks his methods might pose. This made me reluctant to share what I knew about data or what my experience with it was, and I was grateful that day in London to see that he was already wrapping up with Chester’s friends and preparing to leave.

Fortunately, Nix had paid me little attention. When he wasn’t talking about his company, we had chatted in general about my work on campaigns, but I was relieved he hadn’t picked my brain about anything specific to do with Obama’s New Media campaign, any of my work on prevention and exposure of war crimes and criminal justice, or my passion for the use of data in preventive diplomacy. I saw Nix for what he was: someone who used data as a means to an end and who worked, it was clear, for many people in the United States whom I considered my opposition. I seemed to have dodged a bullet.

I thought Chester’s friends wouldn’t choose to work with Nix. His presence and presentation were too large and extravagant, too big for them and for the room. His ebullience had been charming and persuasive; he had even tempered his immodesty with exquisitely honed British manners, but his bluster and ambition were out of proportion with their needs. Nix, though, seemed oblivious to the men’s reserve. As he packed up to leave the restaurant, he prattled on about how he could help them with specially segmented audiences.

When Nix got up from the table, I realized I’d still have time to pitch Chester’s friends. Once Nix was out the door, I intended to approach them now privately, with a simple and modest proposal. But as Nix began to go, Chester gestured to me that I ought to join him in saying a proper good-bye.

Outside in the cold, with the afternoon light waning, Chester and I stood with Nix in a few long seconds of awkward silence. But for as long as I had known him, Chester had never been able to tolerate silence of any length.

“Hey, my Democrat consultant friend, you should hang out with my Republican consultant friend!” he blurted out.

Nix flashed Chester a sudden and strange look, a combination of alarm and annoyance. He clearly didn’t like being caught off guard or told what to do. Still, he reached into his suit coat pocket and pulled out a messy stack of business cards and began shuffling through them. The cards he’d taken out clearly weren’t his. They were of varied sizes and colors, likely from businessmen and potential clients like Chester’s visiting friends, other men to whom he must have pitched his wares on similar Mayfair afternoons.

Finally, when he fished out one of his own cards, he handed it to me with a flourish, waiting while I paused to take it in.

“Alexander James Ashburner Nix,” the card read. From the weight of the paper stock on which it was printed to its serif typeface, it screamed royalty.

“Let me get you drunk and steal your secrets,” Alexander Nix said, and laughed, but I could tell he was only half joking.