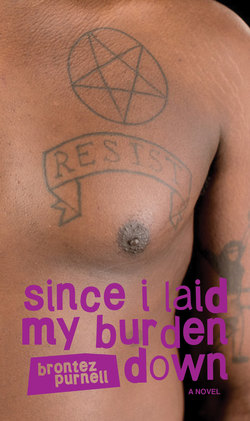

Читать книгу Since I Laid My Burden Down - Brontez Purnell - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPROLOGUE

Hate is a strong word, but sometimes it’s not a strong enough word. DeShawn hated this.

He knew what had brought him back to Alabama. It was all that drinking, drugging, and fucking all those fucking worthless men. It was not any one catastrophe in particular, but all his failures in general. His uncle’s death was just happenstance.

DeShawn got the call while in bed, in California: Your uncle is dead. The sentence punched him in the stomach, hard. He stayed in bed for two days, got up, packed, got on a plane, landed in Nashville, and drove an hour straight to the church. It was tucked deep in the woods, through the cotton fields, and sat on a grassy hill. The creek where he had been baptized almost thirty years earlier ran at the bottom of the hill. He remembered the cold, dirty water, and the preacher with one leg dunking him underwater like a little rag doll.

DeShawn peeked into the church he grew up in, and was shocked by how much hadn’t changed. Maybe it was even moving backward. He entered and was handed a fan by the ushers, the same kind he was handed some thirty years ago as a little boy. It had a wooden handle with a picture of Martin Luther King Jr. or Frederick Douglass or Booker T. Washington. He couldn’t believe they were still using these fans, which were a symbolic gesture, as they really didn’t protect one from the oppressive humidity. Plus, the church had central cooling. As a child in the late eighties, a time before the church had an air conditioner or even a PA system, they only had the fans in the subtropical summer heat. That heat was a nuisance. As a child he would sit on the first pew and look back at the sea of black faces, all frantically fanning.

Before the coming of the PA system, the church choir’s prerequisite was not that one could actually sing, but that one could project their voice to the back of the church. For this reason, DeShawn had led many songs in the children’s choir. He couldn’t carry a tune to save his life, but he could project. These things become metaphors for life if you’re not careful. DeShawn learned it well; projection of voice was everything—be it literal or on paper—as was judicious use of its divine opposite, silence.

DeShawn sat some twenty feet from his uncle’s body and thought about how all open-casket funerals are a son of a bitch. DeShawn told his mother, should anything happen, he wanted to be cremated. “Where do you want your ashes thrown?” asked his mother. “IN THE EYES OF MY ENEMIES!”

There had been this hysterical disease in his family’s bloodline. Growing up, DeShawn watched his granddad and uncle behave like unchecked crazy people. The two men were often drunk, overly emotional, usually crying, exceptionally hysterical, and easily excitable. He remembered that his uncle and granddad had come to blows once when Uncle was eighteen because Granddad wouldn’t let him have the puppy he wanted. All hell broke loose, people took sides, and it ended in a fistfight, a bloody nose, and a gun being pulled. Some children were more susceptible to the hysteria than others. DeShawn grew up and caught the family bug like a motherfucker. Sitting in the church with his baby nephew on his lap, DeShawn wondered if he was going to be a stark raving lunatic too. Only time would tell. He cried and held the baby closer.

Uncle was goddamn handsome as all hell, and hypermasculine. Little DeShawn would wait for him on the porch to get home from high school. He drove a green ’67 Dodge pickup truck. As a little boy, DeShawn would peek at him in the bathroom trying to see him naked. That’s what a man is. Now Uncle really was dead. He was only forty. He’d had cancer since he was thirty-two, but refused to quit smoking. He couldn’t be bothered, really.

The congregation began to rustle in preparation for Sister Pearl. Sister Pearl had been the choir headmistress for forever and a day. She claimed many times that she lost her voice singing for the devil. Sometime in her twenties she decided she wanted to sing the dirty blues, like Aretha Franklin. She quit the church and started singing along the Chitlin Circuit in Chattanooga, Nashville, Louisville, and on up to Chicago. One day, she said, the Lord took her voice away, and that’s when she returned to church. Even as a boy, DeShawn modeled his singing voice after Sister Pearl’s. It wasn’t pretty—it was real. It sounded scratched, beaten, and pulsing with conviction, like she was trying to expel something. DeShawn didn’t care much for her “devil” explanation; like any unrepentant prodigal son, he held that running away with the devil was highly underrated. Sister Pearl’s voice lifted, and she sang “Since I Laid My Burden Down,” the same song she’d sung at his baptism when he was five.

As the processional to the graveyard began, DeShawn’s Auntie Margret got the spirit in her something fierce. She fell to the ground and started screaming, grabbed the casket and wouldn’t let it go. Auntie set off the spark and everyone in the goddamn church lost it; it was a symphony of screams and hollers. Somehow, they made it to the graveyard. DeShawn saw the grave marked JATIUS MCCLANSY and a chill ran though him. But Jatius was a memory for later. He looked away, down the hill to the creek. His baptism was the memory for right now.

DeShawn remembered being five and standing on the steps of the church in a matching white baptism gown and headwrap. All around him the adults were wearing white too. His grandmother kissed his head, and they made the procession down the hill to the creek. Some were holding lit white candles. Two of his girl cousins held his hands, the adults around him holding candles leading him on down to the creek and his uncle, who was chasing away any snakes or snapping turtles that might be lingering. The preacher at the time had lost his right leg to diabetes and had to be helped into the water. He recalled a floating feeling as he was brought midway into the creek to meet his uncles, who were deacons in the church, and the one-legged preacher. “This child has believed with his heart and confessed with his mouth,” said the preacher as he covered DeShawn’s face and pushed him under the creek water; it was cold as hell. DeShawn stood there, submerged, a feeling he could in no way explain.

Up on the bank, Sister Pearl let out a song.

Burden down, Lord.

Burden down.

People don’t treat me like they used too since I laid my burden down.

Every round goes higher and higher . . .

DeShawn’s little soul popped right back up out of the water, feeling cold and wet and not as new as he thought it would.