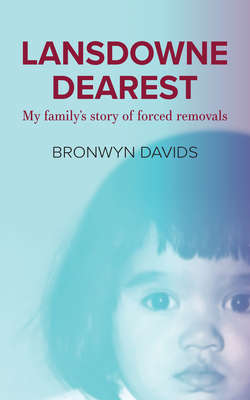

Читать книгу Lansdowne dearest - Bronwyn Davids - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

In my thoughts

ОглавлениеA LONG TIME AGO I used to have another life, very different from the one that I have now. I used to have people I could go to. And they provided a sense of home, generosity and warmth that I am unlikely to find again in this city or anywhere else in the world, come to think of it.

Sometimes I take a trip down memory lane to revisit that life.

I travel by train on the Cape Flats line to Lansdowne Station and take my time walking up Lansdowne Road. I stop off at Shoprite and at Half Price Store to buy colourful balls of yarn for the little girl whose mom I am going to visit.

I pop in at Queen Bess Store and look in at the windows of Mrs Israel’s mishmash of a store. I spend a long time at the Book Swop Shop. Then I stop off at the surgery on the corner of Hanbury Avenue to greet Dor through the dispensary window. Finally, I cross over to the field at bus stop 12 and into Dale Street, to enter the family property via the long, wide backyard driveway.

If I’d come by bus from Claremont, I would have disembarked at bus stop 11 and walked down Lansdowne Road, again stopping off at all the quaint shops: Hamid’s, chock-full of all kinds of everything, Tobias Clothing and Haberdashers, then over the road to see what was playing at The Broadway Bioscope, cross back over to Niefies to check out their British magazines, then back to Lee-Pan’s shop where there are more interesting goods to marvel at – the soft, textured paper, the fountain pens and the different colour inks.

Before the walkabout, I always buy plain Simba or Messaris Chilli chips to munch on, and a Groovy Grapefruit or a Double ‘O’ drink. It’s thirsty and hungry work absorbing the details and images of a place where life was bipolar.

It’s not far to walk down Heatherley Road to reach the side gate to the property. I crunch along the grey gravel aggregate driveway, careful not to get the loose stones in my shoes, past a riot of hedges and creepers on my left. Sometimes I can’t resist climbing up the mound of ochre-coloured gravel – my great-grandfather’s unfinished ideas – impacted hard over decades, before the wooden shuttered window on that side of the house.

On the right side of the driveway, which has parking space for at least four cars, sandstone rocks are placed along the zinc fence draped with morning glory. At the end of the driveway is a pitch-roof garage with barn-style doors, tall enough for a lorry to pass through easily.

Linking the garage to the house is a three-metre-high courtyard wall, originally constructed with grey stone blocks. The walls are covered with lichen, with flashes of bright green moss in the crevices.

I have to jiggle the latch to open the weathered grey shed gate with letterbox number 10. The gate could do with a lick of varnish.

Through the wooden gate, I’m greeted with a cheery ‘Hello, Pretty!’ from the red-plumed parrot Polly. The parrot’s cage is perched on a sandstone rockery, out of which a metres-high Queen of the Night cactus grows. It blooms once a year in the moonlight from dusk to dawn, an event my aunt’s husband likes to record by taking time-lapse photos.

Visits to Lansdowne never fail to provide a feast for the senses, mostly visual. I long to be able to draw or photograph what I see, to capture the many fleeting impressions that change with the seasons.

As soon as I step through that gate, the children stop their games and crowd around me to bombard me with questions or to regale me with far-fetched tales. I know all their names and their odd quirks of character and their even odder turns of phrase.

Whenever I hear the Joan Baez song ‘Children and all that jazz’, which is not often these days, I think of those kids. They don’t live at this house – they only came to play. It is the kind of place and time when children play outdoors all day long, quibbling over the rules of the games and often making up their own as they go along.

And they cross-question unsuspecting visitors about why they’ve been gone so long.

‘I went far away,’ I tell them.

‘Why? Did you go to England? We know lots of aunties who go to England!’

I grin at them. ‘I went away to learn how to listen to people. So that I could write a book.’

‘What book? One with pictures, like Peter Pan?’

‘You bis,’ I say, laughing. Bis their word for ‘busybody’, used when someone asks too many questions.

I tug a few plaits and tickle some stick-people necks. ‘I went away so that I could learn to write an epitaph for a time and a place that no longer exists.’

‘Ohhh!’ they say, in unison. And just like that, they jostle each other to get back to their game, no longer heeding me as I make my way to the always-open grey stable kitchen door.

‘Hello, stranger!’ Mavie says, all smiles. ‘Long time no see! Come in. Sit. Sit, and we’ll have some tea while we chat. There’s still chocolate cake from the weekend.’

She’s excited, as she always is, at the prospect of sharing a good yarn or two. ‘Look at you, burnt to a crisp! And look how long your hair has grown! How was it, over there? How was Spain? How was Portugal?’

Mavie and the house at 10 Heatherley Road is exactly what it is in these journeys: home. My home in Lansdowne, a suburb about ten kilometres southeast of central Cape Town.

At times when the kitchen would be particularly busy, usually with cooking and baking, I would wait out the storm in the sprawling garden, breathing in the fragrances from the fruit trees and luxuriating in the cool shade. Some days I would swing in the swing tied to a branch of the 40-year-old oak tree and dream.

On these trips down memory lane, I go to see how things had turned out for Mavie and family.

Not well, I’m afraid. So much loss and sadness. ‘Home’ was situated in the time of apartheid’s forced removals. There were moves afoot that would drastically alter the lives of hundreds of thousands of people, including my family, the one at Heatherley Road. All these people had the same uncertainty in common. What now? Where to next?

In the 1960s, throughout the city, there was a funereal pall, coupled with a pervasive atmosphere of shame and sadness. There was anger and disappointment at being unfairly treated, humiliated, disrespected, betrayed. All wrapped in a mantle of anxiety, insecurity and tension.

The winds of change blowing through the African continent, that British Prime Minister Harold Macmillan warned the South African government about in February 1960, were gathering momentum. But instead of bringing freedom to South Africans, the wind created disruption and chaos on an unprecedented scale. It would soon reach hurricane status. It lasted for decades, and to this day, the toll is still being counted on the violence-torn Cape Flats.

This is the story of what happened to my family and to me and to everyone we knew during those dark and tumultuous years when whole communities and entire ways of living were lost.

Jose and Minnie Antonio in 1903 with three-year-old Florie beside her mother and cousin Anne.

A young Joey on Chapman’s Peak.

Florentina Antonio in 1913 on her Confirmation day.

Grandma Florie gardening in Goedverwacht, 1962.

A pensive Grandpa Jack, 1950s.

Grandpa Jack, 1963.

A young William outside the wine farm, Vergelegen in Somerset West. Some of Sophie Visser McBain’s family worked and lived here.