Читать книгу Decorative Decoy Carver's Ultimate Painting & Pattern Portfolio, Revised Edition - Bruce Burk - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеGetting Started

FLOATING DECOY CARVINGS

The patterns included in this book depict only the part of the floating bird that is normally seen above the water (the approximate waterline is located at the lower edge of the profile view). If the decoy is to be of the floating type, the height of the body must be increased to provide the necessary buoyancy.

The amount of body that must be added varies, depending on the density of the wood used, the extent of body hollowing, the weight of ballast (if used), and the weight and buoyancy of keel (if used). Usually, one-half to one inch must be added to the body height to make the decoy float with the correct amount of exposed profile.

The carving, hollowing, and floating of decoys are thoroughly covered in other books, therefore no attempt will be made here to cover these design details. (See Bibliography.)

TOPOGRAPHY OF A DUCK

PAINT MIXING

Instructions for mixing the different colors required for the painting of each duck have been included as an aid to the amateur painter who has difficulty in this phase of realistic bird carving.

Standard tube colors (e.g., burnt umber, raw sienna, Thalo blue) vary somewhat, depending on the manufacturer and whether they are oils, acrylics or alkyds. The color-mixing instructions in this book have been based on Grumbacher’s Pre-Tested Oils.

It is most difficult to specify exact proportions of two or more colors required to produce a given color. Also, there may be more than one combination of colors that will give the desired color. The method used here will usually give fair approximations.

The beginner should practice mixing the color formulas described for each duck. This method is also useful when recording for future use the mixing of a color that may have been particularly hard to duplicate.

When matching colors, it may be easier for the amateur painter to cover the color pattern he is using with plastic wrap (or a similar transparent material) and apply a dab of paint directly on the part of the bird being duplicated.

COMPETITION DECOYS

Many carvers are interested in entering their work in some of the decoy contests held in various parts of the country each year. Competition, both formal and informal, has been an important factor in the steady improvement of realistic bird carving from its rather humble beginning to its highly developed present state. Carvers, from the rankest amateur to the seasoned professional, can learn a great deal by participating in these contests. Most carvers are friendly and helpful and are willing to share their experiences and provide constructive criticism. A carver with an open mind cannot go home from one of these shows without having acquired new ideas and better techniques—plus having had a good time and having renewed his enthusiasm for his hobby.

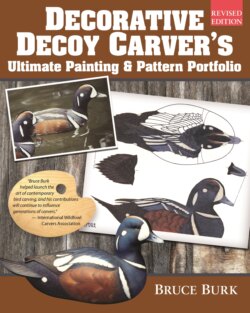

Fig. 1: Fine harlequin drake decorative floating decoy by Joe Girtner, Brea, California. (Photo by Joe Girtner.)

There are three popular classes for decoy carvers in most competitive shows. The floating decorative decoy class (sometimes designated by other names) is the most popular. Decoys in this class are made to depict the actual duck as realistically as possible, not only in shape and detail but also in colors. These carvings may be as elaborate and as detailed as desired—fragility is not a factor. They must float realistically but need not be self-righting. Most carvings in this class are hollow and are usually without keels (see Fig. 1).

Fig. 2: Ring-necked drake and lesser scaup drake service or gunning stool class decoys by author. (Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Keith Rogers, Burbank, California.)

The service, or gunning stool, class is probably the second most popular. These decoys are made somewhat like the old working decoys. They must bear an unmistakable likeness, in form and color, to the species and sex they represent. Usually incorporating much less detail than decorative decoys, they are made more ruggedly, with no fragile parts. Tails are made much thicker and the wing primaries are not raised, or undercut, from the body. They must float realistically and must be self-righting, a feature that necessitates keels. Anchor attachments must be provided. Their surfaces are usually not textured (see Fig. 2).

Fig. 3: Pintail hen by the author. Typical decorative non-floating decoy. (Collection of Tim Eagan, California.)

The strictly decorative non-floating class is the least popular, mainly because these carvings must compete with elaborate, full-bodied standing or flying carvings. The requirements are the same as for the floating decorative class except that these decoys are never floated (see Fig. 3).

The Ward Foundation World Championship Wildfowl Carving Competition held at Ocean City, Maryland, features a fourth class called the World Championship Class Competition Grade Floating Waterfowl. Both the male and the female of the species must be entered as a pair. These carvings may be as detailed and as elaborate as desired and are often full-bodied, complete with legs and feet. They must float realistically but need not be self-righting.

Inasmuch as there are some variations in the rules for the different decoy shows, the carver should ascertain them in advance before spending a lot of time on his entries.

To promote interest in competitive decoy shows, a definite distinction is made in regard to experience and proficiency. Most shows have broken this competition phase into three categories: novice, amateur and professional classes. Again, there are variations in the rules, and carvers who are not in the professional class should establish their personal status prior to entering.

PATTERN CHANGES

The serious bird carver should make every effort to introduce changes to patterns done by others. At present, there is such an abundance of material designed to aid the beginning and intermediate bird carver that it is very easy to follow the path of least resistance and copy existing patterns and carvings rather than to do the research and planning required for original work. The successful carvers and blue-ribbon winners of today take full advantage of all available reference materials to aid them in the planning and execution of their unique works. In addition (and of equal importance), they study live birds at every opportunity to ascertain and check details. An original design usually requires a great deal of work; nevertheless, the personal satisfaction of knowing one has created, rather than copied, is well worth the effort involved.

Making changes to existing patterns is a start toward gaining the experience required for developing the original drawings. Head rotation is the simplest modification to make. Instead of making the decoy’s head point straight ahead, you can rotate it up to about 30 degrees in either direction without greatly affecting the neck lines. (See here.) If you decide to rotate the head, make the head-body joint parallel to the base of the carving; otherwise, the turned head will be tilted to one side. The duck in a sleeping position is a good example of extreme head rotation (see Fig. 4, 5, 6). Convolutions of the neck in this pose are complex. To duplicate this position accurately, photographs such as those referred to above are a necessity.

Fig. 4, 5, and 6: Classical sleeping pose.

The next easiest change is to alter the head position (see Fig. 7–10). The position of the head is most important as it usually establishes the activity of the duck—relaxing, preening, displaying, drinking, feeding, attacking and so on. At least three alternate head positions are included in this book for each sex of the various species. It is a simple matter to develop others. Start out by tracing the profile of the head and bill onto a piece of paper, and then cut it out. Place this cutout on the color pattern, move it to the desired position, and blend in the neck and chest lines. Next, make a new profile pattern by tracing off the original body and the newly positioned head. Photographs of live birds in different positions can be most helpful in developing new head positions and working out new neck and chest lines.

Fig. 7: Ring-necked drake with head turned.

Fig. 8: Drinking position.

Fig. 9: Rear view of a canvasback drake.

Fig. 10: An alert canvasback drake.

Opening or closing the tail is another relatively easy change to make. When on the water, the duck normally has its tail closed. The tail is expanded during some activities such as preening, attacking, stretching and others. Most of the patterns in this book show the tail somewhat expanded so that the shape and size of the individual feathers can be ascertained.

Raising or lowering the tail relative to the water, with a resulting change in angle, is also a simple alteration. Raising the tail can impart a feeling of alertness, and the resulting overall configuration is usually more pleasing (see here). Diving ducks, however, unlike dabbling ducks, generally hold their tails low, often in the water. Exceptions to this generalization can be seen in the photographs accompanying the patterns of the diving ducks in this book.

Fig. 11: Preening female harlequin duck. Note the exposed wing.

Fig. 12: Barrow’s goldeneye drake in an aggressive pose.

Fig. 13: Barrow’s goldeneye male scratching his head.

Changing the angle of the duck’s body relative to the water is another easily achieved modification. Ducks, when swimming or feeding, often submerge more of their breasts and chests, exposing more of the rear part of their bodies. Typically, the bodies of diving ducks are more nearly parallel to the water than those of dabbling ducks.

The feeling of aggression can be simulated by the head position and the open bill (see Fig. 12). Raising the folded primary wing-feather groups can also impart the feeling of alertness and aggressiveness.

When relaxing, ducks often lower their wings, sometimes uncrossing them (see here).

Advanced amateur and intermediate carvers should attempt more complicated alterations. The preening bird offers a variety of very pleasing and artistic poses (see here). Often, the wing is partially exposed, adding new challenges for the carver (see Fig. 11). Floating ducks sometimes roll over on one side while preening and expose one leg and foot, providing still another advanced pose. In a similar position, the duck may use its foot to scratch its head, supplying the ingredients for another interesting, if rather difficult, pose to duplicate (see Fig. 13).

It is strongly recommended that the amateur decoy carver use the books listed in the bibliography, not only for carving and painting instruction but also for making alterations to existing drawings or patterns and for making new drawings.