Читать книгу Backpacking Arizona - Bruce Grubbs - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеIntroduction

This book is a backpacker’s guide to hiking in Arizona. While many hiking guides cover Arizona, all of them emphasize day hikes. Backpacking Arizona primarily describes backpacking trips of three to six days, although a few overnight hikes and several trips of a week or longer are included.

Experienced local hikers know that backpacking is one of the best ways to enjoy Arizona’s incredible diversity and beauty. Carrying all you need to live comfortably in the wilderness for days at a time gives the hiker a satisfying feeling of self-sufficiency. Such a “house on your back” enables the backpacker to travel deep into the backcountry, far beyond the reach of hikers limited to a single day. In all but a few places, Arizona backpackers are free to camp nearly anywhere, at sites whose pristine beauty is beyond the imagination of the legions of vehicle recreationists who camp in a few designated campgrounds or heavily overused roadside campsites. Backpacking loads don’t have to be heavy, although some trips do require you to carry heavy water loads. Modern lightweight equipment greatly reduces the load on your back, and there’s a large selection of high-tech packs available that make carrying your gear surprisingly comfortable.

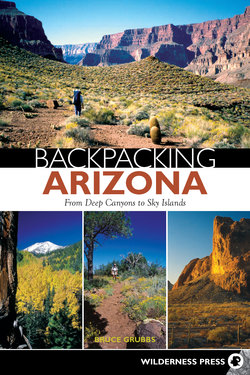

In Arizona, you can hike through deep canyons, listening to the music of a desert creek and the soft rustle of cottonwood leaves. You can walk the crest of a forested mountain range through cool sylvan glades, observing the shimmering heat of the desert vistas far below through the trembling aspen leaves. You can spend ten days or more wandering the depths of a great canyon system, where even human footprints are rare. You can loop from cactus-studded desert to forested mountains and back to the desert, without seeing another person for days on end, and never be more than fifty miles from the state’s largest city.

The backpacking trips described in this book are necessarily a reflection of my experience. While I have attempted to present a selection of the best backpack trips in the state, no roomful of Arizona backpackers could ever agree on such a list. You’ll notice right away that the majority of trips are loops. In my opinion, loops are the best backpack trips. Loops eliminate the need for a second vehicle for a car shuttle, and they make the most of your valuable backpacking vacation time. The last thing a backpacker wants to do is spend a day bouncing over dusty roads instead of walking gently through the backcountry. You’ll find only two out-and-back hikes in this book, both through country so unique and beautiful that you’ll not mind seeing the same scenery twice. Of course, there are some great backpack trips that just can’t be done as loops. These trips use trailheads that are as close together as possible, or have commercial shuttle services or public transit available.

Guidebook writers face an unpleasant dilemma. Such books tend to attract large crowds of people to the described areas. On the other hand, without people who have experienced and appreciated the backcountry, wilderness will have no defenders. Long ago I decided that the risks of large invasions are more than offset by the larger voice they create for the defense of wild country. And make no mistake—the forces of development, driven by people who honestly feel that every corner of the planet should be exploited for human use and corporate profit, are relentless. Only an aware citizenry can stand up for places and creatures that cannot speak for themselves.

That said, every backpacker shares the responsibility to leave no trace of his or her presence. Arizona wilderness is dry, plants are slow growing, and litter lasts for centuries. Adopt the United States Forest Service’s “Pack it in, pack it out” slogan. Simply put, if you carried it in, you can carry it out. Never bury or burn any sort of trash. Animals dig up food scraps, and man-made materials such as plastics degrade slowly or not at all. Most backcountry litter is accidental, and we can all help by packing out a bit of litter on every trip.

When following a trail, stay on it and do not cut switchbacks. Taking shortcuts greatly increases erosion and trail maintenance costs, and you’ll always expend more energy than if you followed on the trail. When hiking cross-country, avoid fragile terrain such as cryptobiotic soil as much as possible. Cryptobiotic soil is a thin crust of cooperating plants that forms in desert areas, and especially in pinyon pine and juniper forests. The fragile crust protects the sandy soil from erosion and takes many years to reform once crushed. Don’t build rock cairns to mark your cross-country route. Such markers diminish the next backpacker’s experience and aren’t necessary.

Desert scenery along the Tonto Plateau

Many hikers, including some backpackers, enjoy experiencing the wilderness with their four-footed companions. I like dogs, but please remember that not every backpacker does, and no one appreciates having their backcountry experience marred by dogs that bark or run up to them in an intimidating way. Also, dogs are a menacing presence to most wildlife, and certain predators will attempt to entice your dog away from you. Dogs are not allowed on trails or in the backcountry of most national parks. In national forests, dogs must be kept under control at all times, either by voice command or leash. If your dog runs up to other backpackers, chases wildlife, and does not come instantly at your command, it is not under control and must be on a leash or left at home.

Camping causes the most damage to the backcountry, but good equipment and technique can alleviate nearly all impact. The use of high-quality shelters (tarps, bivi sacks, or tents), sleeping bags, and sleeping pads completely eliminate the need to “improve” a site for comfort, warmth, or safety. The worst campsite “improvement” is a campfire ring. Campfire scars, often full of unburnable trash, mar far too many beautiful places. Never build campfires, except in an emergency. If you have a lightweight, warm sleeping bag and jacket, you’ll stay warmer than you would huddling around a campfire. You’ll also get to enjoy the wider worlds of night sounds, smells, and sky instead of a small circle of smoky light.

If you do build a campfire, never leave it unattended. Before leaving camp, put your fire out completely. To do this, mix the coals with water repeatedly until there is no heat or smoke, then feel the ashes with your hands to make certain it is out. If you can’t do this, your fire is not out. If you don’t have enough water, use dirt. This accomplishes the same thing as water but takes longer. Never leave a campfire or bury it in dirt. Campfires can easily escape from under a layer of dirt. Abandoned campfires have caused some of Arizona’s worst wildfires, including one that burned the entire Four Peaks Wilderness in 1966: more than 60,000 acres were burned. Smoking is another common cause of wildfires. In the national forests, it is illegal to smoke while traveling along the trails or cross-country. Smokers are required to stop and clear a two-foot circle to bare earth, and then make certain that all smoking materials are extinguished before leaving.

Superstition Wilderness

Once away from facilities, most people have little knowledge of basic human sanitation. Fortunately, the word has spread among backpackers and most seem to know what to do, but Arizona’s dry climate warrants special consideration. Since springs, water pockets, creeks, and rivers are especially precious here, make an extra effort to answer the call of nature at least one hundred yards from any water, preferably further. The normal practice of digging a small “cat hole” for your waste works well, except in barren, sandy soil. Try to find a spot where the soil is rich in organic material, if possible. Most rangers and land managers now recommend that all used toilet paper should be carried out. It is slow to degrade in the dry climate, and burning it poses an unacceptable fire hazard much of the year. Pack it out in doubled zipper plastic bags, and add a bit of baking soda to control the odor.

Camp at Fish Creek, Superstition Wilderness, Trip 21

HOW TO USE THIS GUIDE

Scenery

This is the author’s opinion of the trip’s overall scenic beauty, on a scale of 1 (ugly) to 10 (unsurpassed). Obviously this rating is highly subjective and dependent on the author’s tastes. Remember that all of the trips have been carefully selected from a plethora of candidates, and all of them are scenic. Some are more scenic than others, so use this rating as a guide to relative scenic qualities.

Solitude

Most backpackers prize solitude. With this rating, you can get an idea of the degree of solitude to expect, from 1 (you’ll be elbowing your way through crowds) to 10 (you won’t see a soul, even on holiday weekends). Remember that even popular, crowded areas may be very lonely during mid-week and off-season. On the other hand, a quiet, remote area may be invaded by a large group sponsored by an organization.

Difficulty

This is another subjective rating that is intended to rate a trip’s difficulty in relation to other backpack trips. Dayhikers unaccustomed to carrying heavy loads will probably find the easiest of these trips to be strenuous, and couch potato non-hikers will have a very tough time. If you have some backpacking experience, expect a 1 to be a straightforward hike on good trails. At the other extreme, you’ll find that a 10 will probably have such obstacles as serious cross-country walking, tedious bushwhacking, difficult navigation, scarce water sources, and possible rock scrambling where packs may have to be hauled and some group members may want a belay. Backpackers attempting these most difficult trips should be fit, and at least one member of the party should be an experienced desert backpacker. Most trips in this book fall in between these limits.

Miles

This is basic mileage for the primary trip, with no side trips or options. Since official trail mileage varies widely in accuracy, the author measured the trip distance on 1:24000 scale U.S.G.S. topographic maps. Such map-derived distances tend to be slightly shorter than mileages measured with a trail wheel on the ground, but they are very consistent. A second mileage figure in parentheses below the primary number gives the total distance for the primary trip and all optional side trips described. Some of the loop trips have short-cut options that make the loop shorter. In this case the mileage in parentheses is less than the main loop mileage.

Elevation Gain

This number is an attempt to give the total elevation gain on the primary trip. It doesn’t count minor ups and downs that are too small to show on a U.S.G.S. 1:24000 topographic map. A second number in parentheses shows the elevation gain or loss for the primary trip plus all optional side trips. Some of the loop trips have short-cut options. In this case the elevation gain in parentheses may be less than that of the main loop.

Days

One hiker’s three-day backpack trip is another’s dayhike! Nevertheless, this number is the author’s recommendation, based on an average of 8 miles per day—a reasonable figure with a big pack in rough country. This figure is strongly influenced by the availability and spacing of water sources and good campsites. A second number in parentheses below the first gives the number of days required for the primary trip and all optional side trips in the description. Some of the loop hikes have an optional short cut, so the number of days required may be less.

Shuttle Mileage

If this number is 0, and the trip is a loop or an out-and-back hike, no shuttle is required. Otherwise, it shows the shortest driving distance between the beginning and ending trailheads. Remember to schedule enough time at the start and end of your hike to drive the shuttles. In a few areas, it’s possible to hire a shuttle service that will drop you off at the starting trailhead, and then move your vehicle to the exit trailhead. Such services save a lot of time, and are listed under the contact information if available.

Maps

Each hike in the book includes an accurate sketch map to give you a general idea of the layout of the trip. You should also carry a topographic map covering the area. The most detailed maps are the U.S.G.S. 7.5 minute series of quadrangles, and the names of the maps covering the hike are always listed. If there is also an agency-issued or privately produced wilderness or recreation map covering the hike, its name is listed. These maps may have less terrain detail, but road and trail information is usually updated more often.

Season

The months listed are those in which the hike is possible, either snow-free for mountain hikes, or when the weather is reasonably cool for desert hikes.

Best

These months represent my opinion of when it’s the best time to do the trip, a decision that is strongly influenced by the availability of water. Lesser factors include fall colors and wildflowers. Of course, most areas are at their most crowded during the best season; if solitude is your primary consideration, consider an off-season.

Water

The availability of water controls the planning of most Arizona backpack trips. This section lists all known springs, natural tanks, water pockets, and streams along the hike. I use the term “seasonal” to refer to creeks and springs that may have water only during the cool season and after wet weather. Very few water sources can be considered permanent.

Warning: Never depend on any single water source, and always have an alternate route, or even retreat, in mind if water sources are unexpectedly dry. All backcountry water should be purified before use, by chemical treatment, a water filter, or by boiling.

Permits

Permits are required for some of the hikes in this book, and in certain areas only a limited number of backpackers are allowed. The permit requirements at the time of writing are described, but since the permit situation is changing rapidly on Arizona public lands, you should contact the land management agency before your trip for the latest information.

Rules

As land managers deal with increasing impact on the backcountry, they are often forced to impose special rules on hikers, such as campfire restrictions and group size limits. These rules are listed here, but do not include common backcountry rules such as the requirement to leave no trace, keep pets quiet and under control, and pack out everything you brought in.

Contact

This is the telephone number for the local land management agency that is responsible for the area of the hike. I also list a web site if a useful one is available. It’s a good idea to call ahead and check on road and trail conditions, as well as permits and special requirements.

Highlights

This paragraph focuses on outstanding features such as the opportunity to see wildlife, exceptional views, narrow canyons, and other appealing attributes.

Problems

Unusual difficulties such as lack of water, poorly maintained trails, rough access roads, crowds, and other potential problems are listed here. Please remember that it’s impossible for a book to list all the problems you may encounter in remote country.

How to Get There

This section describes the best access route from the nearest sizable town. Alternate routes are listed where appropriate, as is the route to the end of the hike if a shuttle is required. With a few exceptions, you’ll need a vehicle to get to these backpack trips. While you can reach some trailheads on paved roads, most require travel on dirt roads that can be traversed by a normal vehicle. Some approaches do require high-clearance or four-wheel-drive vehicles. Because some trailheads are very remote, it’s a good idea to carry extra water, food, and a change of clothes in your vehicle.

Description and Tips and Warnings

The detailed description includes clear navigation directions using natural landmarks and trail signs. Directions are given as left and right, and are backed up with the compass direction in parentheses. Although mileages between trail junctions are provided, the emphasis is placed on natural landmarks since mileage is difficult to measure in the backcountry and trail signs may be damaged or missing. Cross-country routes are described entirely by landmarks. Tips and Warnings are based on the author’s experience and are embedded in the text to call your attention to things that may make your trip safer and more enjoyable.

Possible Itinerary

A suggested plan for the primary trip is listed after the description, based on the author’s experience on the route. This may or may not include side trips. Side trips are clearly labeled as such. Treat itinerary as a starting point for your own trip planning, remembering that such things as water availability, trail conditions, and the fitness and experience level of the group will affect your final itinerary.

Optional Side Hikes, Shortcuts, and Alternate Routes

These are mentioned by name in the main description of each hike. An optional side hike offers you the chance to explore a feature, trail, or route off the main hike. These are usually done as out-and-back dayhikes. A shortcut is an optional route that shortens the length of the overall trip. An alternate route is an optional trail or route that is the same length or longer than the main trip.

Conquistador Aisle from The Esplanade, Grand Canyon National Park