Читать книгу Balinese Temples - Bruce Granquist - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеOf Gods and Men

Unlike their Indian counterparts, Balinese shrines and sanctuaries do no: generally include a physical representation of the deity to whom they are dedicated. There are, however, exceptions, as i the case of the Pura Penulisan, situated high on the crater walls surrounding Gunung Batur, where one finds this fine example of a stone lingga (below). In Hindu iconography, the lingga is a representation of the god Siwa, the phallic symbolism of the image being a celebration of the creative aspect of the deity. The veneration of the Hindu god Siwa plays an important role in Balinese religion, but lingga are usually found only in the oldest sanctuaries. Evidently the disappearance of a physical representation of the deity is something that happened after the introduction of Hinduism to Bali.

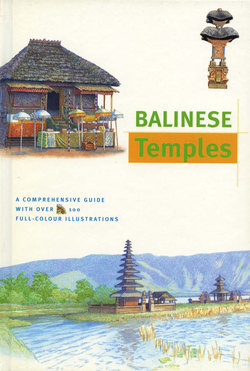

There are literally tens of thousands of temples and shrines on the island of Bali, a proliferation of religious architecture which probably is not equalled anywhere else in the world. Glimpsed through a screen of trees, or.across a swathe of verdant rice fields, the Balinese temple seems almost to be a part of the natural order of things. Closer to hand, the crumbling brick work and lichen-cohered statuary convey a sense of considerable antiquity, while the astonishing sculptural repertoire of demonic masks, multi-limbed deities and lurid depictions of sexuality that confront the Western eye, conjure up an exotic otherness of 'lost' civilisations and licentious natives—the 'Mysterious East' of all good Orientalist fantasies.

But Balinese temples need not be quite so mysterious if one takes an informed look at the underlying logic which determines the layout of the sanctuary and the symbolic significance of individual structures in the temple precincts.

Balinese Religion

The religion of Bali represents an eclectic blend of Hindu and Buddhist beliefs laid over a much older stratum of indigenous animism, and it is this combination of native and exotic influences which informs so much of Balinese life. The introduction of Indian religious beliefs to Southeast Asia began about the time of Christ and represents not so much a story of conquest and colonisation as one of cultural assimilation which followed in the wake of burgeoning trade links with the subcontinent. In the case of Bali, bronze edicts, written in Old Balinese, testify to the existence of an Indian-style court by the end of the 9th century, but Balinese Hinduism, as we know it today, owes more to East Javanese influences between the 14th and 16th centuries. The latter have subsequently been shaped by local traditions to create a singular form of Hinduism peculiar to the island.

Reincarnation and a Cosmic Order

Hinduism is founded on the assumption of a cosmic order which extends to every aspect of the universe right down to the very smallest particle. This organising principle, or dhama, manifests itself in the persona of the gods, while demonic figures represent agents of disorder and chaos. As far as man is concerned he must try to conduct himself in a manner which is in keeping with his own personal dharma, the ultimate aim here being to gain liberation (moksa) from the endless cycle of reincarnation or rebirth to which he is otherwise destined. This objective can only be achieved by establishing a harmonious relationship with the rest of the universe, a beatific state which requires the subjugation of all worldly desires.

Microcosm and Macrocosm

Being in harmony with the rest of the universe requires, among other things, that one be correctly oriented in space. These ideas are represented, on the ground so to speak, in terms of local topographical features and the cardinal directions, which are attributed specific ritual and cosmological significations. In this respect, the island of Bali is conceived as a replica of the universe in miniature—a microcosm of the macrocosm.

Central to this scheme of things, is the idea of a tripartite universe consisting of an underworld (bubr), inhabited by demons and malevolent spirits; the world of men (buwah); and the heavens (swah), where the gods and deified ancestors reside. In Bali, the mountains are conceived as the holiest part of the island while the sea is cast as a region of impurity and malign influences; mankind is sandwiched in between, tending to his rice fields and visiting his temples to pay his obeisances to the gods and placate the forces of evil.

A Tripartite Universe

The Balinese division of the universe (tri loka) into three domains-buhr, buwah and swah-dovetails with the concept of tri angga which posits that everything in the Balinese cosmos can be similarly divided into three components: nista, madya and utama. These categories are hierarchically ordered in terms of a set of spatial coordinates-high, middle and low-which in the case of human beings find a corporeal correspondence in a division of the body into three constituent parts-head, torso and feet. Buildings and other man-made objects can similarly be divided into three components. A simple column, for example, consists of a base, a shaft and a capital. This tripartite scheme of things ultimately extends to everything in the universe, from the Hindu trinity (trimurti) of Brahma, Siwa and Vishnu, to the works of man, including the temples that he builds, reflecting an essential unity underlying the whole of creation.