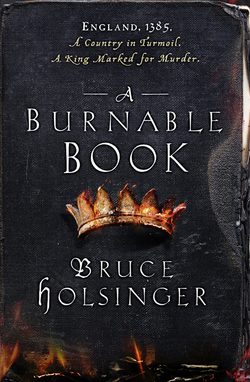

Читать книгу A Burnable Book - Bruce Holsinger - Страница 24

FOURTEEN Cutter Lane, Southwark

ОглавлениеHook out the belly, knot up the guts, snip out the anus – all that was fine, but Gerald still had trouble with the hiding. How to keep it one piece when it wants to split apart at the shoulders, that was the thing. As Grimes liked to remind him, a split hide wasn’t worth half a whole, and you’ll get the hole, boy, get it right through your pate ’f you split another vellum on me.

This time it worked. Gerald grunted happily as he felt the spine, pared to the haunch, begin to loosen against the gored skin. Spines had their own smell, too, that chalky air of fresh bone. He pulled it free. Hard part of this calf was done. He felt his arms loosen, the knife working its magic as he sliced and split with the ease of a stronger, bigger man.

Gerald loved butchery, felt he was born to cut up these beasts. Only bad part was Grimes. His master was inside now, prattling with that priest. He’d first shown up two weeks ago. This was his third visit. Gerald could hear them all the way from the cutting floor, their voices raised in an argument of some kind. Same as last time.

The priest’s comings and goings were putting Grimes in a bad state, even worse than usual. More blows to the cheek, more boxes to the ear, more threats of worse to come. Part of him knew his brother was right – well, his sister – his broster, his sither, whichever way in God’s name Edgar–Eleanor was swerving these days, it was true that Grimes’s shop wasn’t a safe place for a boy Gerald’s age. Better to be back in London, with its laws. But what could he do about it? What could Edgar do, for that matter – let alone Eleanor? He shook his head, trying to put it all out of his mind and concentrate on the carcass swinging in his face.

Tom Nayler came in, wiping his hands. ‘I’m off, then,’ he said, tossing his chin in the direction of the high street. ‘Got a coney to slit up the market. This’ll wait, yeah?’

‘Suit yourself,’ Gerald said, wondering who the lucky girl was this time. Tom had a way with the daughters of oystermongers and maudlyns. ‘I’ll finish this one up. Not a lot left.’

Tom ambled off. Gerald sliced and cut contentedly for a while longer. Flanks, legs, heart, with the offal for the dogs. The master’s shop had grown quiet, though he hadn’t seen the priest leave. He stepped off the floor and glanced up the alley. Tom Nayler was long gone. After a look in the other direction he wiped his blade, set it down on a board, and stared at the shop, his thoughts churning.

What was it with Grimes and this priest? Wasn’t a parson of the parish, that was sure. Gerald knew the local parson, just like he’d known the parson at St Nicholas Shambles in his younger days. No, this one wasn’t a Southwark man. Not even a Londoner. A northerner, maybe. Or a Welshman. Talked with a gummy twang, like his words were tangled up in brambles and couldn’t get out.

The only window on this side of the shop was shuttered, as usual when important visitors came to talk to Grimes. The butcher liked to keep his inquisitive apprentices at bay. Taking his time, Gerald walked over to the shop, found the right spot, and pressed his ear to the gap between the boards. More than once he’d saved his hide this way, catching snatches of the master’s complaints about his apprentices and correcting himself accordingly.

He heard the priest, speaking low. At first none of it made sense. A lot of talk about how Grimes had to listen, had to do this and that, think about his future. Then, a stream of verse. ‘Listen to it, Nathan Grimes. It’s you this prophecy is talking about, you and your cutters over here.

By bank of a bishop shall butchers abide,

To nest, by God’s name, with knives in hand,

Then springen in service at spiritus sung.

Butchers, Nathan. Butchers bearing knives. They’re to be the blood of it, and you the heart.’

Grand words. But what did they mean? Gerald heard Grimes clear his throat. ‘Lots of butchers in London, Father, over in the Shambles and such. There’s nothing in the verse to say it’s to be a Southwark meater, is there?’

‘Not exactly, no,’ said the priest slowly. ‘But “bank of a bishop”? And later it reads “In palace of prelate with pearls all appointed.” That’s Winchester’s palace, my son, you know it as well as I. And who’s the closest master butcher to Winchester’s palace? Nathan Grimes, that’s who.’

‘Nathan Grimes,’ said the butcher, tasting his name.

‘That’s right. “By kingmaker’s cunning a king to unking.” Do you see?’

‘Well—’

‘It’s plain as the shining sun, Nathan Grimes. Look in the glass. You’re to be the kingmaker, sure as I’m standing here.’

‘The kingmaker,’ Grimes repeated.

‘Wouldn’t be the first time you’ve been at the centre of such great events,’ said the priest, lowering his voice. ‘You were on the bridge with Wat Tyler, Nathan. You walked right behind him. And I saw you myself on Blackheath, standing at Ball’s feet. You could have taken out King Richard at Mile End, with a cleaver or a long knife.’

Gerald felt a chill, finally understanding the priest’s cryptic talk. It had been four years since the Rising, when the commons of Essex and Kent, infuriated by the poll taxes and the harshness of their levy, had flooded London by the thousands, burning buildings, beheading bishops and treasurers and chancellors, imprisoning the young King Richard himself in the Tower and nearly executing him at Smithfield.

The butchers of London and Southwark had marched along with the rest, and Gerald could still remember the exuberance on the streets as word spread of John Ball’s sermon on Blackheath. When Adam delved and Eve span, who was then the gentleman? Words of hope, and a promise of a better life for England’s poor. Though things were now much the way they had been before the Rising, its wounds were still fresh, the city and the realm braced with suspicion of the commons. You could still see it on the faces of the beadles and aldermen, in the tense stance of lords and ladies as they rode through the streets, trading hostile glances with clusters of workers breaking stone, or lame beggars idling by the gates.

Now, it seemed, the talk of treason was back. That priest in with Grimes, he was trying to convince the master butcher to raise arms again, and this time have a real go at the king. He thought of the priest’s verses. By bank of a bishop shall butchers abide. Not one butcher, not Nathan Grimes alone, but butchers. So what did that mean for him, Gerald Rykener?

The scrape of a bench. Gerald turned his head so his eye was against the gap. The priest rose and clapped Grimes on the back. ‘This is fate, my son. It’s prophecy, as sure as the Apocalypse itself. God sees our futures and our glories in ways we mortals cannot, Nathan. This is yours. Embrace it, my son!’

Grimes sat there, staring at the far wall of his shop, kneading his swarthy chin. Gerald watched him, almost seeing the muddled thoughts in his master’s brain, like a rocker churning cream. Then the butcher looked up at the priest, a gleam in his eye. He stood, inhaled deeply, and nodded.

‘I’m in, Father.’ His nod strengthened as his certainty swelled. The priest stepped in and embraced him.

Gerald felt his stomach heave. He turned away, his eyes cast at the ground as he trudged back to the kill shed. He leaned against the rough board wall, pondering what he’d heard.

The butchers of Southwark. A new Rising. Knives and cleavers and axes and a crowd of meaters, massing over the bridge, intent on killing the very King of England. To what end? He shook his head, the answer as clear as his memory. A rain of arrows, the swish of a garrison’s swords, and it would all be over. A slaughter in the streets, the blood of the poor running between the pavers. Just like last time.

And who would the hangman come for first, once the king’s men discovered who sparked this certain treason? Gerald looked up, the fear clenching at his middle so he could hardly stand straight. Nathan Grimes, that’s who – and his two apprentices, all of them about as safe as the butchered veal calf hanging there before him.