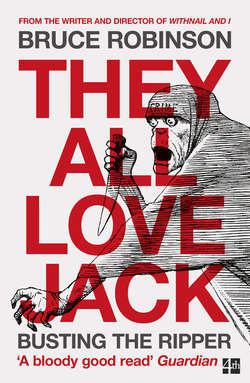

Читать книгу They All Love Jack: Busting the Ripper - Bruce Robinson - Страница 12

5 The Savages

ОглавлениеClench the fingers of the right hand, extend the thumb, place it on the abdomen, and move it upwards to the chin, as if ripping open the body with a knife.

Richardson’s Monitor of Freemasonry (1860)

The ‘Double Event’, as the Stride/Eddowes murders were christened by their perpetrator, is not original to the ‘Saucy Jacky’ postcard he sent, but was a vulgar colloquialism of the age. It meant to simultaneously suffer venereal disease of both the anus and the genitals. Jack’s choice of such a pleasantry may be trivial, but I don’t think it is. Although characteristic of a pun, I think it had a more substantive meaning for the murderer, and I interpret the ‘Double Event’ as both sobriquet and expression of disgust.1

The Ripper’s choice of target was opportunistic, but not accidental. Self-evidently he was looking for a ‘type’, his selection of a victim in life no less specific than the signature he wrote into their deaths. This fabulously cruel man didn’t rip the ‘sex’ out of East End whores because he lacked the wit to kill elsewhere. He killed in Whitechapel as part of his statement. He wanted ‘sex’ as low as it got. The furnace of his rage was in his victim’s womb, the ‘filthiest part’ of her being, and he was disgusted with her for what his hatred would have him do.

Theories seeking to link these women to their killer (as in Clarence) are as risible as the use Freemasonry attempts to make of them. The victims were linked only in circumstance, and insomuch as they were available. As far as this narrative is concerned, Catherine Eddowes’ life lasted about thirty-five minutes: from the time she left the police lock-up to the time the Ripper killed her. Many accounts detail what’s known of her past, her lousy life and those in it, but none of that is of much interest here. Eddowes’ biography matters no more to me than it did to the man who eviscerated her. On her drunken arrest earlier that evening she gave her name as ‘Nothing’, and that’s just about it. She was just another bit of trash in the ugly East End rain.

A psychopath is at his most dangerous when he’s having fun. Jack was having a lot of fun, playing off the angels and the ogres in his own homicidal fairy tale. Authority would feel the weight of his spite, and women the depths of his revenge. Angels don’t fuck, and in the vernacular of his hatred, I believe that’s how Jack saw women, as either mother-angels or whores. It’s my view that he killed these women as surrogates, punishing them for the sexuality of another, and I believe one woman in particular was on his mind. She was a mother-angel who had proved herself lower than the filthiest whore. Until he got to her, and destroyed her, he owned her in Eddowes and the rest, cut out her mother-part for a trophy, like a huntsman with the head of a vanquished animal. He was ‘walking with God’, as the great detective Robert Ressler characterises the mindset of such a psyche, and what fault there was belonged to the victims.

‘It wasn’t fuckin’ wrong,’ claimed American serial killer Kenneth Bianchi. ‘Why’s it wrong to get rid of some cunts?’2

‘Four more cunts to add to my little collection,’ brags a letter signed ‘Jack the Ripper’ (dismissed with infantile pomp by Ripperology as a hoax).

Eddowes was a cunt, and the Ripper put his hands inside her and excoriated what he pulled out, literally hated her guts.

The question, then as now, is: who was he? Dozens of writers – some admirable, many not – have taken their shot. The list of candidates is phenomenal. If all the Rippers had been in the East End on the same night they’d have been elbowing into each other up the alleyways. There would have been about thirty Fiends out there at first fog. It’s worth a glance at a few of the names. They were (and are) Kosminski, Ostrog, Druitt, Klosowski, Clarence, Pizer, Gull, Austin, Cutbush, Cream, Sickert, Isenchmid, and James Maybrick.

None of the above was remotely plausible as far as I was concerned. But when the name Maybrick turned up, I was interested. As I intended to set out in the Author’s Note at the beginning of this book, but didn’t, my curiosity about tackling a murder mystery kicked off with reading Raymond Chandler. In his memoir, published in 1962, the inimitable crime writer nominated the case of Florence Maybrick as one of classic forensic interest. Exploring it over about a dozen pages, he concludes that evidence of her guilt is cancelled out by evidence of her innocence, and that the resulting conundrum remains insoluble. What made the name Maybrick interesting to me was that it was not only already associated with an unresolved murder mystery but, many years after Chandler’s death, with the mother mystery of them all.

This development, reprising the name Maybrick, came via a ‘scrapbook’ that emerged in Liverpool in 1992, provenance unexplained. Ludicrously misnamed as ‘The Diary of Jack the Ripper’,3 it implicated James Maybrick as our famous purger. Beyond Chandler, I knew nothing about James Maybrick, or the mystery surrounding his wife either, but considering both were accused (albeit over a hundred years apart) of being famous murderers, I thought both were worth a closer look.

In 1880 James Maybrick was a forty-one-year-old Liverpool-based cotton broker who had met and wooed Florence Chandler, a seventeen-year-old Alabama beauty, on an Atlantic crossing. Their wedding the following year was the biggest mistake of her life. Eight years later, and now with two kids, Florence was about to take her seat in the front row of a nightmare.

It doesn’t take long to dismiss James (or ‘Jim’, as he was nicknamed) as Jack. As a candidate for the Fiend, he suffers from two immediately apparent disqualifications. Firstly, in May 1889 he was supposed to have been murdered by Florence, who in gaslit tradition poisoned him with arsenic soaked out of flypapers. A bowl of such liquid was discovered at their Liverpool residence, and bingo – the System that framed her had both evidence and motive. Florence (who was having an affair with a younger man) was accused of disposing of her much older husband with periodic doses of her lethal soup. The problem with this scenario is that James Maybrick was a lifelong arsenic addict, or as Raymond Chandler put it, ‘Why Doesn’t an Arsenic Eater Know When He’s Eating Arsenic?’ If Florence had been attempting to cull him with his favourite hit, he’d have sought out her stash, quaffed the lot, and probably asked for more. The second and insurmountable problem for the fans of James is self-evident. Jack the Ripper was in the business of murdering women, not being murdered by one of them – particularly not by Florence, who in the scrapbook is apparently the focus of his homicidal rage.

Anyone who thinks this fifty-one-year-old arsenic-head was going to sprawl on his deathbed while some scatterbrained girl murders him with his drug of choice might not be best qualified to examine the complexities of the so-called ‘Maybrick Mystery’. But ‘the Liverpool Document’ suggests just that. Its misleading christening by excited publishers as a ‘diary’ is something I don’t want to get into.

As a matter of fact, I don’t want to get into this document at all. Argument and counter-argument as to its authenticity is entirely counterproductive. Apparently various scientists, graphologists, ionising-ink experts, ultraviolet paper buffs, and even a clairvoyant have examined it. One proves it’s genuine, another proves it isn’t, and they’re all wasting their time. Personally, I couldn’t give a toss whether it’s real, fake, or written in Sanskrit. This document and its association with the word ‘mystery’ means you’ve got to junk all the crap and start thinking sideways. There’s an ancient Chinese adage: ‘When a finger points at the moon, the imbecile looks at the finger.’ Not that I’m accusing devotees of James Maybrick of imbecility, simply that they’re up the right arsehole on the wrong elephant.

Only two things about this document are of any interest to me: 1) The name Maybrick (which the text doesn’t actually mention); and 2) Its potent association with Freemasonry (which the text doesn’t mention either).

James Maybrick’s Freemasonry has been guarded as a precious ingredient of the ‘mystery’ for about 130 years, and as far as I’m aware is here made public for the first time. In a later chapter it will become clear why such effort has been lavished on keeping it a secret, and when you know it, you understand why.

James was a prominent Liverpool businessman, a provincial Mason of zeal and eminence, ‘initiated into the mysteries and privileges of Freemasonry’ on 28 September 1870, although he was clearly unaware of what kind of ‘mystery’ he was going to get. He remained an enthusiastic Freemason until the day of his murder in Liverpool in May 1889.4

It was almost certainly James who introduced his younger and equally zealous Freemasonic brother Michael to the Craft. He was initiated into the Athenaeum Lodge (1491), London, on 3 May 1876, at the age of thirty-five. Michael was a successful singer, songwriter and composer, a rising star heading for the glittering pinnacle of Victorian society. He knew everyone who was worth knowing, sharing especial friendship with Sir Arthur Sullivan and Sir Frederick Leighton, intimates of the Prince of Wales. Both Michael and James were Master Masons (M.M.) as well as initiates of Christian degrees (both eighteenth-degree) as practised under the aegis of the Holy Royal Arch.

But a more comprehensive biography must wait. For the moment, I want only to demonstrate how these brothers – both blood and Craft – were associated by Masonic osmosis with the Victorian Establishment, what Henry Austin called ‘government within government’, and my grandfather called ‘wheels within wheels’.5

I need briefly to return to the squabble of experts over the veracity of the Liverpool Document. The nub of the issue rests on a discovery made in the City of London archives by Mr Donald Rumbelow, a historian of notable expertise in Whitechapel matters to whom the record owes much. In 1987 Mr Rumbelow unearthed an original police list of Catherine Eddowes’ possessions, taken at or about the time her mutilated body was undressed for autopsy.

An officer, probably a policeman, recorded them as another called them out. One of the items he listed was

Tin Matchbox Empty

These three words are absolutely vital to the association of the name Maybrick with Jack the Ripper. ‘Tin Matchbox Empty’ is a perfectly reasonable statement for a copper in a gaslit shed in London in September 1888, but it tends to look a bit iffy on its reappearance in a scrapbook discovered in Liverpool about a hundred years later. The salient question is framed accurately by Mr Martin Fido, who writes: ‘This undoubted fact [the existence of the empty tin matchbox] was not in the public domain until 1987, so the journal [scrapbook] is either genuine or a very modern forgery.’6

It couldn’t be clearer, and I couldn’t agree more. If whoever wrote the scrapbook had means of knowing about the ‘Tin Matchbox Empty’ contemporaneously with the Ripper, then it is genuine, and has an unimpeachable association with the name Maybrick.

On the other hand, if there is no discernible source for this information, we’re left with the animated opinion of veteran Ripperologist Mr Melvin Harris. ‘Fido printed the police-list of Eddowes’ belongings,’ he writes, ‘and this provided the “diary” fakers with some telling references, and [Ripper author] Paul Feldman fell for them.’

And so did a lot of others. There are entrenched arguments on either side, with a lot of exclamation marks in between. On one side are disciples of the Harris school of certainties, and on the other individuals with a more open mind. I let Mr Harris speak for the former, disseminating characteristic misconceptions with his usual small-calibre popgun.

‘Feld’, as he uncharitably calls Feldman, ‘creates a little drama around one item [the empty matchbox]’, and ‘goes on to take up a page brooding over the mystery’. ‘There is no mystery,’ he squawks, ‘since the Diary is a modern forgery.’ The tin matchbox ‘was not in print until 1987, the fakers seizing on the box and other items, simply in order to scribe lines of doggerel’:

One whore no good, decided Sir Jim strike another

I showed no fright, and indeed no light.

Damn it, the tin box was empty.7

I’m sorry Mr Harris is no longer with us, but as my grandmother used to say of such personages, he was all hat and no drawers. Had he got off his one-eyed microscope and been able to widen his field of vision, he might well have been intrigued by a piece in Lloyd’s Weekly, dated 30 September 1888, published literally within hours of the ‘Double Event’.

Lloyd’s was the first newspaper in London to carry an account of the murders. It was a scoop shared in part by the Observer, which also reported the slaying of Mrs Stride and Mrs Eddowes on the very morning following their deaths.

The first thing I wanted to know was, who was the author of the Lloyd’s report?

At an early hour this [Sunday] morning two women were found murdered in the East End of London … many of the horrors of the recent Whitechapel murders are found to be repeated … Information of the crimes was quickly sent to the police stations of the district, and doctors were immediately summoned, the first to arrive being Mr F. Gordon Brown and Mr Sequeria. They made a minute examination of the body [Eddowes], Dr Gordon Brown taking a pencil sketch of the exact position in which it was found. This he most kindly showed to the representative of Lloyd’s when subsequently explaining the frightful injuries inflicted upon the body of the deceased.8

The emphasis is mine, banged in to demonstrate that Dr Gordon Brown was not averse to showing confidential material to certain friends in the press. The Lloyd’s reporter was there with his notebook while the frightful injuries were ‘explained’, and equally present while the police composed their list, ‘Tin Matchbox Empty’ and all. He was the only reporter allowed into the Golden Lane mortuary that night, where he could have taken notes in respect of Dr Brown’s sketch, a copy of the police itinerary, or anything else from the accommodating City Police physician. Indeed, there is first-hand evidence that he did, that Dr Brown shared ‘secrets’ with this journalist – ‘more than could be published’, he wrote. We will come to them by and by.

‘At twenty minutes past five [a.m.],’ records the Lloyd’s reporter, ‘we left the mortuary after the interview most kindly accorded by Dr Gordon Brown.’9 The journalist who conducted this exclusive interview in the presence of Eddowes’ corpse and effects was Bro Thomas Catling, Worshipful Master of the Savage Lodge, habitué of the Savage Club, and intimate of fellow member Bro Michael Maybrick.

The ‘Savage’ was a bohemian hangout for writers, artists, musicians and journalists. According to an official club memoir of the time, ‘There is no place in the world, perhaps, where more amusing copy can be picked up than is to be had for the asking at the Savage Club.’10 Everyone in London was talking about Jack, and it’s no stretch to imagine what an informed ‘Ripper insider’ might be telling his fellow members in the smoking room of the Savage – and Catling was known for his mouth. ‘Mr Catling tells us of his astounding feats in nosing out copy,’ continues the memoir, ‘in obtaining the earliest information in respect of murder … For obvious reasons many of the good things are not for publication.’ This was the currency of smoking-room gossip, ‘to be had for the asking’ at the club.11

Thus, from Catling’s notebook to a dozen eager ears (including those, I hazard, of Michael Maybrick), the unpublishable details of Mitre Square were told. That a Liverpool cotton broker could have known about an empty tin matchbox in London’s East End is, I’m afraid, no great mystery, but is in fact rather mundane. From Bro Catling to Bro Michael, and then passed just as easily to James. He was Michael’s brother, and a frequent visitor to his London residence at Regent’s Park. Had either written the so-called ‘Diary’, the mysterious ‘inside information’ becomes no mystery at all.

Does that not blow a rather sizeable hole in Harris’s misplaced certainty that prior to 1987 there is no possible way that James Maybrick could have known about the matchbox? Either one of the Brothers Maybrick could comfortably have been aware of this information ninety-nine years before Mr Rumbelow rediscovered it. Ergo, the Liverpool ‘scrapbook’ purporting to have been written by Jack the Ripper can easily be associated with the name Maybrick, via Bro Thomas Catling.

Too abstruse for the Harris school? All right, let’s knock Catling out of the equation and go directly to the source. I refer to none other than the man up to his elbows in Catherine Eddowes’ guts, forty-five-year-old surgeon to the City Police and fellow of the ‘Mystic Tie’ since 1868, Bro Dr Frederick Gordon Brown.

Brown, with his gregarious tongue, would have been even more worth listening to than Catling – presupposing you had a particular interest in the case, and were inclined to ask. Like Catling, Dr Brown was a regular on the Maybrick circuit, sharing more than one enclave of rendezvous. He was a member of both the Savage Club and the Savage Club Lodge (2190), a pal of top London nobs and a familiar figure on the social scene.12

According to the weekly The Freemason, under the heading ‘Grand Lodge Representatives’ we learn that ‘To represent another Grand Body near one’s own is considered a very high honour.’ Bro Dr Gordon Brown and Bro Michael Maybrick did precisely that at a Grand Soirée at the Holborn Restaurant, a favoured haunt of members of Orpheus Lodge. Maybrick was co-founder of Orpheus Lodge and Chapter (1706), which later in this book will get a chapter of its own. On the night in question, Saturday, 26 October 1889, ‘Grand Lodge was represented by Bros Edwin Lott P.G.O., Doctor Gordon Brown G.S. and Michael Maybrick P.M.’

When the speeches started, it is recorded that ‘In responding for the Grand Lodge Officers, Bro Maybrick remarked that the position he held as G.Org. [Grand Organist] reflected honour upon the Lodge, because he believed he owed his office to the fact of his being Past Master of the Lodge.’ Bro Dr Gordon Brown ‘made effective replies for the visitors who were strong in force’. ‘The commendably short speeches,’ continues The Freemason, ‘were interrupted with music. Bro Maybrick sang the solos of the National Anthem.’13

Though the events of the evening took place in 1889, there is abundant evidence that Dr Brown and Michael Maybrick were well known to each other a good time before that. The initials ‘GS’ after Brown’s name stand for Grand Steward. He was first elected in this capacity of service to Grand Lodge in 1887. The following year he took a breather, becoming PGS (Past Grand Steward), and we find him as such together with GO Michael Maybrick at a Grand Lodge celebration in that same year, its ensuing banquet presided over by none other than ‘I thought they were girls’ the Earl of Euston. ‘A beautiful vocal and instrumental concert was given under the direction of Bro Sir Arthur Sullivan,’ one of Maybrick’s close melodious pals.

The Lord Mayor of London, Bro Sir Polydore de Keyser, was a prominent member of the exalted who were present. Among the newly elected Senior Grand Deacons was Bro Edmund Ashworth, a fellow member of James Maybrick’s St George’s Lodge of Harmony at Liverpool. Bro the Earl of Lathom was in the chair, supported by Bro Hugh Sandeman, thirty-third degree, Past Grand District Master of Bengal and member of Michael Maybrick’s St George’s Chapter (42), London.

The ‘Mystic Tie’ could not be more in evidence, and it returns us briefly to the Liverpool of James Maybrick. ‘It is a truism,’ announced The Freemason of 20 October 1888, ‘to say that West Lancashire (wherein is Liverpool) is one of the strongholds of Freemasonry in this country.’ A Past Master and very present member of James Maybrick’s St George’s Lodge of Harmony was Colonel Le Grande Starkie, an enormously wealthy landowner with 12,000 acres of Lancashire to prove it. Another member was Lord Skelmersdale, a.k.a. the above-mentioned Earl of Lathom, who like Starkie had a few fields out of town. Lathom was old money and a lot of it, and, second only to the Prince of Wales himself, the most important Freemason in England. At his seat at Ormskirk in 1888 he threw a week of parties celebrating a visit to the province by the Prime Minister Lord Salisbury and his wife, but under less festive circumstances his duties were usually confined to London.

Earl Lathom was Lord Chamberlain to Her Majesty the Queen, entrusted with the ‘well being of her swans’ and, on a more prosaic level, vetting guest lists for the Palace soirées. To this end he wore an enormous symbolic ceremonial key, a reminder that ‘everyone the Queen receives must wear the white flower of a blameless life’ – which makes one wonder how half her relatives got in. The picture opposite shows him in business at the Palace (he’s the man in tights with the long beard), standing next to Edward’s wife, the Princess of Wales, who was herself standing in for Queen Victoria. The Prince himself is to the right, under the chandelier, and to his right is the bald bulk of Prime Minister Lord Salisbury.

Concurrent with the ceremonial key and the organisation of the Masonic affairs of Lancashire, the Earl, among a select few, was also a member of a London Obligation, once again named in honour of St George. This was St George’s Chapter (42), a confluence of well-heeled members of the Masonic hierarchy wherein we discover fellow member Bro Michael Maybrick. Thus, with membership of (32) in Liverpool and (42) in London, Lord Chamberlain to the Queen Bro the Earl of Lathom forms a distinctive link between the Masonic activities of Bros Michael and James Maybrick.

But you would never know it, unless you were prepared for a very protracted search indeed. As far as the records at Freemasons’ Hall in London are concerned, James Maybrick wasn’t even a Freemason. As will become clear, he has been quite spirited away. This presents a dilemma for the researcher, to which we can add the elusiveness of Chapter (42). Like Lord Euston’s exclusive ‘Encampment of the Cross of Christ’, of which Michael was also a member, (42) is not to be found on Michael Maybrick’s c.v. Indeed, there is a palpable absent-mindedness surrounding it.

Meanwhile, on 23 April 1888, St George’s Chapter (42) presented an MWS Jewel (Most Wise Sovereign of a Rose Croix Chapter) to Bro Michael Maybrick ‘for services rendered during the past year’.14 His award was conferred by a galaxy of eminence, representing some of the most distinguished names in English Masonry. Only one need detain us.

Colonel Thomas Henry Shadwell Clerke, author of the quote at the beginning of Chapter 3, Grand Secretary of English Freemasons and liaison officer between Masonry and the Prince of Wales, was a close personal friend of Michael Maybrick.15 Whenever Edward failed to show, which was just about always, it was Shadwell Clerke who made the apologies. ‘As regards H.R.H.,’ he was oft to say, ‘the brethren must not fancy, because they do not see him at their meetings, that he is neglectful of the Craft.’ He (Clerke) could assure them from personal knowledge that HRH ‘took the greatest interest in all that concerned Masonry’. When their MWGM (Most Worshipful Grand Master) was in London, he (Clerke) ‘was in constant attendance at Marlborough House, for all matters of importance were submitted to H.R.H.’. And further, if they couldn’t have the fat man, ‘The names of Lord Carnarvon and Lathom were well known, for these two Brethren exercised a watchful care over all that affected Freemasonry.’

In the matter of James Maybrick, more watchful eyes could hardly be imagined. But back to Bro Michael, who was no less eminent a Mason than Lathom and Clerke, serving, as they did, as an Officer of the Grand Lodge, a body constituting the zenith of Freemasonic authority in the land.

I put Michael Maybrick into the picture not with the intention of impugning anyone around him, but to demonstrate just how much a part of the picture he was. Maybrick was no less a public celebrity than he was (in occult places) a celebrated Freemason, both facts that put him inside the inner social circles of London’s greatest past-master of decadence, Edward, Prince of Wales.

Nothing encapsulates this more succinctly than his membership of the Savage. Maybrick joined on 5 July 1880, preceding His Royal Highness’s initiation by a couple of years. By the time Maybrick walked through its portals at 6–7 Adelphi Terrace, the club had elevated itself into something of significance, opening its doors to ‘practitioners of every branch of science, including the law, with the result that Music Hall Stars, political cartoonists and actor-managers rubbed shoulders with distinguished lawyers such as Bro Lord Justice Moulton, Bro Sir Richard Webster, Bro Sir Edward Clerke Q.C.’ and many more who have made or will make themselves known to this narrative.

The most illustrious of them all, Edward, Prince of Wales, was invited to become a lifetime honorary member on the occasion of the club’s twenty-fifth anniversary, in April 1882. He was further invited to nominate one or two pals as special guests, and selected a duo who wouldn’t have spoiled Michael Maybrick’s evening, because, at the risk of labouring it, Sir Arthur Sullivan and Sir Frederick Leighton were special friends of his too.

It’s perhaps worth pointing out that, just as Michael Maybrick was one of Sullivan’s closest friends, so too was Sir Charles Russell QC MP, making subsequent events at the High Court in Liverpool more than somewhat mind-blowing. (It was Russell who was to ‘defend’ Florence Maybrick against the charge of murdering her husband James.)

But I’ve run out of detour, and return to the Savage and its special gala night. It was what the Victorians liked to describe as ‘a singular occasion’, with actors, musicians, singers and wits all eager to do their dazzling thing. Among them was Wilhelm Ganz, a leading light in Masonic and musical circles, and long a friend of Michael Maybrick. By coincidence, Ganz lived a few doors down from Sir Charles Russell in Harley Street.

‘The entertainment which followed the annual dinner, was similar to that which occurs every Saturday evening,’ wrote the man from the Illustrated London News, ‘and Mr Harry Furniss has happily depicted the best points of it in our engraving.’

Michael Maybrick is represented at the piano (middle row, second from right). His performance that evening was preceded by Mr George Grossmith’s rendition of ‘Itinerant Niggers’, the fun of which must have contrasted agreeably with the pathos of Maybrick’s ‘The Midshipmite’, his hit song from 1879.

Leighton, Sullivan, Russell and Maybrick were fellow Savages and fellow Masons. They were among the men ‘in the know’, as Rudyard Kipling put it, who between politics and Freemasonry and the law knew just about everything there was to know. Like His Royal Highness’s plenipotentiary Bro Sir Francis Knollys, ‘who saw everything, heard everything, and was consulted about everything for forty-two years’, and who, above all, ‘knew how to be silent’, so did this confederacy of savages.16

In 1888 the Worshipful Master of the Savage Lodge was J. Somers Vine MP, installed in February of that year at Freemasons’ Hall by Maybrick’s fraternal pal Bro Colonel Thomas Shadwell Clerke, in the presence of a distinguished assembly that included the Earl of Lathom. Almost exactly a year later the proceedings were replicated for the incoming Worshipful Master, Bro Thomas Catling. On the grand night of installation, Catling put all propriety aside and rose amidst the toasts to propose ‘the election of an honorary member of the Savage Club Lodge, the Right Worshipful H.R.H., Prince Albert Victor, the Duke of Clarence’.

Clarence’s membership was unanimously approved and applauded, but not every member had been able to attend. The future Commander of Her Majesty’s Army, Bro Lord Wolseley, regretted that the pressure of official duties precluded his presence, a sentiment echoed by the Lord Chancellor, Bro Lord Halsbury. Further apologies were received from a Brother who wrote that he ‘had been looking forward with great pleasure to the evening’s entertainment, but was prevented by sudden indisposition’, leaving one wondering just what Police Commissioner Sir Charles Warren was busy with.17

With Thomas Catling and Dr Gordon Brown (and possibly even Sir Charles Warren) as fraternal associates of Michael Maybrick, both (short of murdering her themselves) were as intimate as it got to the slaying of Catherine Eddowes. It becomes incredible to claim their supposed first publication in 1987 as a disqualification for the authenticity of the words ‘Damn it, the tin box was empty’ in the Liverpool Document.

It was in the course of my research into Michael Maybrick that I discovered that his brother James was a Freemason. This wasn’t without interest, because I was certain Michael had murdered James, and framed James’s wife Florence for the deed. I was also certain that the flagrancy of the Masonic ‘clues’ decorating the crime scenes in Whitechapel was grist to the enterprise, as indeed was his so-called ‘diary’. In other words, they were the work of a crazy Mason, or someone trying to blame one. It wasn’t just Florence who was to be framed. It was also Brother Jim. James was not only married to an American, but had spent years living in the United States. Hence the ‘Americanisms’ in the Ripper correspondence (of which more later). The clues Jack left were the servants of a unique criminal, and presented an intriguing scenario.

But with James Maybrick in ceremonial apron, the jigsaw began to shape up. The Ripper was flaunting Freemasonry, and James was a murdered Freemason whose Masonry was suppressed by Freemasons. You don’t have to be Sherlock Holmes to find something of interest in that. As has been mentioned, James has been considered by some as a Ripper candidate. Mr Paul Feldman wrote a sizeable book about just such a possibility,18 as did Mrs Shirley Harrison. Between them these two authors share perhaps a decade of research, yet neither of them, and subsequently no one plaguing the internet for twenty years after, has ever discovered James Maybrick’s ‘Masonic secret’.19

The obvious question is, why not? The equally obvious answer is that certain parties had gone to quite astonishing lengths to cover it up. In fact, as much effort has gone into exorcising James Maybrick’s Masonic career as has been applied to camouflaging the Ripper’s Masonic pantomime in the East End. They are opposite ends of the same stick, each lopped off for precisely the same reason. Jack’s Masonic contribution was expunged by the police as they pretended to investigate his crimes, while James’s Masonic secret was posthumously imposed by Freemasons themselves.

As far as publicly available records are concerned, James Maybrick was not a Freemason. Freemasons’ Hall in London had never heard of him. ‘Further to your enquiry we have checked our records for the above name without success,’ was their honest response – honest because he’d been cleaned out a very long time ago. Such frustrations were ignored as I looked for another source, my researcher Keith later mining a basement at a Liverpool library where we finally got lucky. I now had an abundance of proof that the poor murdered bastard was a Bro. Intense enquiry at last resulted in a letter from Supreme Council (Royal Arch), together with a document. It purports to suggest that James was indeed a Freemason, but only briefly, between perfection (i.e. induction) on 24 January 1873 and resignation in 1874.

Although it looks the part – i.e. it is Victorian – it took only seconds to realise that this document was decidedly iffy. It’s titled ‘Return of Members of the *** *** *** Liverpool Chapter *** Liverpool’.

Liverpool Chapter by the name and number of what? (Apparently by the name and number of ****.) By now I knew rather a lot about my subject, was familiar in fact with most of the long-forgotten names that appeared with James on the Chapter’s members’ list. Like him, many were cotton brokers, and one or two instantly stood out. Horace Seymour Alpass, by way of example, was listed as ‘mort’ (dead) in 1881, when in reality he was very much alive, expiring, according to his death certificate, on 31 August 1884. By contrast, James Gaskell, soundly dead on 26 April 1868, is here listed as paying his Masonic dues in November 1873. James Maybrick’s ‘resignation’ is equally problematic. Reliance on this document would give the impression that he quit Masonry in 1874, when in fact at that date his Masonic career was poised to flourish.

Meanwhile, a fascinating paradox has presented itself. We now consider two candidates who were Freemasons – a half-witted homosexual son of the heir to the throne of England, and an arsenic-eating middle-aged cotton broker from Liverpool. Bro Clarence and Bro James share Masonry in common, but manifest vastly different provenances. It was a distinguished Freemason, the aforementioned Bro Thomas Stowell, who brought Clarence’s name into the public domain as a bogus Ripper suspect, and it was Freemasonry that since 1889 had kept James Maybrick out of it. Upon Maybrick’s demise the System was panicked into believing it had urgent reason for denying his Masonry, and simultaneously silencing his wife. When the time came, the Establishment closed ranks, abandoning James like a man with plague, denying his Masonry even if it meant hanging an innocent woman. The Crown got up phoney charges against Florence, and in a ‘trial’ as filthy and corrupt as any on God’s earth, consigned her to life imprisonment. This is known as ‘the Maybrick Mystery’, an adjunct of mind-boggling wickedness sharing its taproot with ‘the Mystery of Jack the Ripper’.

Both ‘mysteries’ were fabricated to protect the ruling elite, and Bro Michael Maybrick was the nucleus of both.