Читать книгу Marx and Freud in Latin America - Bruno Bosteels - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPREFACE

The least that may be said today about Marxism is that, without attenuating prefixes such as “post” or “neo,” its mere mention has become an unmistakable sign of obsolescence. Thus, while the old manuals of historical and dialectical materialism from the Soviet Academy of Sciences keep piling up in secondhand bookstores from Mexico City to Tierra del Fuego, almost nobody seems any longer to be referring to Marxism as a vital doctrine of political or historical intervention. Rather, in the eyes of the not-so-silent majority, Marx and Marxism have become things of the past. In the best of all scenarios, they simply constitute an object for nostalgic or academic commemorations; in the worst, they stand accused in the world-historical tribunal of crimes against humanity. “Guevarists, Trotskyists, libertarians, revolutionary syndicalists, radical third worldists, and anti-Stalinist communists have all been sent back to the dock to appear before the prosecutors of ‘really-existing’ capitalism in the great trial of communism,” Olivier Besancenot and Michael Löwy write in their recent proposal to retrieve the figure of Ernesto Guevara. “This is a trial that places executioners and victims, revolutionaries and counter-revolutionaries side by side. Not to accept capitalism is a crime in itself.”1 And while the same fate has not befallen the works of Freud and his followers, even in their case hardly anyone can keep a straight face when remembering the attempts to weld together the Marxist and psychoanalytical notions of praxis—respectively, the political revolution and the talking cure—into a combined Freudo-Marxism.

Not only have the scientific credentials of psychoanalysis come under increasing attack but so too has the idea of an emancipatory potential behind the discovery of the unconscious. Even on purely therapeutic grounds, the virtues of psychoanalysis seem to have been trumped by the pharmaceutical industry. In 1993, Time magazine thus famously was able to put the Viennese doctor on its cover alongside the rhetorical question “Is Freud dead?” Yet, as Anthony Elliott admonished, “Despite the fluctuating fortunes of psychoanalysis, Freud’s impact has perhaps never been as far-reaching,” albeit now for reasons that are more political than clinical. “In a century that has seen totalitarianism, Hiroshima, Auschwitz and the prospect of a nuclear winter, intellectuals have demanded a language able to grapple with culture’s unleashing of its unprecedented powers of destruction. Freud has provided that conceptual vocabulary.”2 Beyond providing a far-reaching, if also gloomy, diagnostic of the human condition as well as an intriguing conceptual vocabulary that has penetrated everyday use, however, the question is still very much open as to whether Freud’s work might also enable us to envision the radical transformation of our current political situation in ways reminiscent of the promise behind the legacy of Marx and Marxism.

Álvaro García Linera, the current vice-president of Bolivia under Evo Morales, in an important text from 1996 written from prison, where he was being held in maximum security conditions on charges of subversive and terrorist activity—a text titled “Three Challenges for Marxism to Face the New Millennium,” and included in the collective volume The Arms of Utopia: Heretical Provocations in Marxism—describes the situation as follows:

Yesterday’s rebels who captivated the poor peasants with the fury of their subversive language, today find themselves at the helm of dazzling private companies and NGOs that continue to ride the martyred backs of the same peasants previously summoned . . . Russia, China, Poland, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Communist and socialist parties, armed and unarmed “vanguards” without a soul these days no longer orient any impetus of social redemption nor do they emblematize any commitment to just and fair dissatisfaction; they symbolize a massive historical sham.3

With regard to the destiny of Marx’s works and the politics associated with them, however, something else appears to be happening as well. The story is not just the usual one of crime, deception, and betrayal. There are whole generations who know little or nothing about those “rebels of yesteryear,” and much less understand how they would have been able to “captivate” the impoverished peasants and workers with the “fury” of their language.

On the one hand, all memory seems to have been broken, and many radical intellectuals and activists from the 1960s and ’70s—for a variety of motives that include guilt, shame, the risk of infamy, or purely and simply the fear of ridicule if they were to vindicate their old fidelities—are accomplices to the oblivion insofar as they refuse to work through, in a quasi-analytical sense of the expression, the internal genealogy of their militant experiences. Thus, the fury of subversion remains, unelaborated, in the drawer of nostalgias, with precious few militants publicly risking the ordeal of self-criticism. What is more, the situation hardly changes if, on the other hand, we are also made privy to the opposite excess, as a wealth of personal testimonies and confessions accumulates in which the inflation of memory seems to be little more than another, more spectacular form of the same forgetfulness. As in the case of the polemic about militancy and violence unleashed in Argentina by the recent epistolary confession of Óscar del Barco (“No matarás: Thou shalt not kill”4), we certainly are treated to a heated debate, but what still remains partially hidden from view is the politico-theoretical archive and everything that might be contained therein, in terms of relevant materials for rethinking the effective legacy of Marx and Marxism in Latin America. And we could argue that the same is true, though with less spectacular effect because oblivion also has been more spontaneous, of that strange hybrid of Freudo-Marxism in Latin America.

How to go against the complacency that is barely concealed behind this bipolar consensus, with its furtive silences on the one hand and its clamorous self-accusations on the other? In the first place, we should insist on something that we know only too well when it comes to domestic appliances, but that we prefer to ignore when we approach the creations of the intellect—namely, the fact that everything that is produced and consumed in this world bears from the start a certain expiration date, or the stamp of a planned obsolescence. Theories do not escape this rule, no matter how much it pains scholars and intellectuals to admit it. As a secondary effect of this obsolescence, however, we should also consider the possibility that novelty may be nothing more than the outcome of a prior oblivion. As Jorge Luis Borges remarks in the epigraph to his story “The Immortal,” quoting Francis Bacon’s Essays: “Solomon saith: There is no new thing upon the earth. So that as Plato had an imagination, that all knowledge was but remembrance; so Solomon giveth his sentence, that all novelty is but oblivion.”5 This grave pronouncement applies equally to the products of criticism and theory. Here, too, all novelty is perhaps but oblivion.

In fact, the history of the concepts used in studies of politics, art, literature, and culture as well as their combination in what we can still call critical theory today appears to be riddled with holes that are very much due to the kind of silence mentioned above—a not-saying that is partly the result of voluntary omissions and partly the effect of unconscious or phantasmatic slippages. Forgetfulness, in other words, is never entirely by chance, nor can it be attributed simply to a taste for novelty on the part of overzealous artists or intellectuals in search of personal fame and fortune. After all, as the Situationist Guy Debord had already observed more than twenty years ago, in his Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, itself a reflection upon his book from twenty years before: “Spectacular domination’s first priority was to eradicate historical knowledge in general; beginning with just about all rational information and commentary on the most recent past.” And, about the events of 1968 in particular, Debord adds: “The more important something is, the more it is hidden. Nothing in the last twenty years has been so thoroughly coated in obedient lies as the history of May 1968.”6 If today, more than forty years after the original publication of The Society of the Spectacle, the vast majority of radicals from the 1960s and ’70s dedicate mere elegies to the twilight of their broken idols, those who were barely born at the time can only guess where all the elephants have gone to die while radical thinking disguises itself in one fancy terminology after another, each more delightfully innovative and invariably pathbreaking than the previous novelty. Thus, instead of a true polemic, let alone a genealogical work of counter-memory, what comes to dominate is a manic-depressive oscillation between silence and noise, easily coopted and swept up in the frenzied celebrations in honor of the death of communism and the worldwide victory of neoliberalism.

The current appeal of cultural studies, for example, beyond its official birthplaces in the Frankfurt and Birmingham Schools, is inseparable from a process of oblivion or interruption whereby critics and theorists seem to have lost track of the once very lively debates about the causality and efficacy of symbolic practices—debates that until the late 1960s and early ’70s were dominated by the inevitable legacies of Marx and Marxism. In the United States, where these legacies never achieved a culturally dominant status to begin with, any potential they might have had was further curtailed by the effects of deconstruction, whose earlier textual trend was then only partially compensated for both by deconstruction’s own turn to ethics and politics and by its short-lived rivalry with new historicism. As for Latin America, if we were to ask ourselves in which countries the model of cultural studies, or cultural critique, has achieved a notable degree of intellectual intensity and academic respectability, the answers—Argentina, Chile, Brazil—almost without exception include regions where the military regimes put a violent end to the radicalization of left-wing intellectual life, including a brutal stop to all public debates about the revolutionary promise of Marxism, while in other countries—Mexico or Cuba, for instance—many authors for years might seem to have been doing cultural criticism already, albeit sans le savoir, like Molière’s comedian, perhaps because in these cases the influence of Marxism, though certainly also waning today, has nevertheless remained a strong undercurrent.

In Latin America, the reasons for amnesia are if possible even more complex. Not only has there been an obvious interruption of memory due to the military coups and the onslaught of neoliberalism but, in addition, this lack of a continuous dialogue with the realities of the region can already be found in the works of Marx and Freud themselves. In fact, we could say that the history of the relation of Marx and Freud to Latin America is the history of a triple desencuentro, or a three-fold missed encounter.

In the first place, we find a missed encounter already within the writings of Marx. Thanks to José Aricó’s classic and long out-of-print study, Marx y América Latina, now finally reissued, we can unravel the possible reasons behind Marx’s inability to approach the realities of Latin America with even a modicum of sympathy. His infamous attack on Simón Bolívar (whom Marx in a letter to Engels labels “the most dastardly, most miserable and meanest of blackguards”7) or his and Engels’s notorious early support for the US invasion of Mexico (about whose inhabitants Marx, in another letter to his collaborator, wrote: “The Spanish are completely degenerate. But a degenerate Spaniard, a Mexican, is an ideal. All the Spanish vices, braggadocio, swagger and Don Quixotry, raised to the third power, but little or nothing of the steadiness which the Spaniards possess”8) are indeed compatible with three major prejudices that Aricó attributes to Marx: a belief in the linearity of history; a generalized anti-Bonapartism; and a theory of the nation-state inherited, albeit in inverted form, from Hegel, according to which there cannot exist a lasting form of the state without the prior presence of a strong sense of national unity at the level of bourgeois civil society—a sense of unity and identity whose absence or insufficiency, on the other hand, tends to provoke precisely the intervention of despotic or dictatorial figures à la Bonaparte and Bolívar. In this sense, the three prejudices are intimately related: it is only due to a supposedly linear conception of history that all countries must necessarily pass through the same process of political and economic development in the formation of a civil society sufficiently strong to support the apparatuses of the state.

One paradox alluded to in Aricó’s study, however, still deserves to be unpacked in greater detail. Especially in his final texts on Ireland, Poland, Russia, or India, after 1870, Marx indeed begins to catch a glimpse of the logic of the uneven development of capitalism, which could have served him as well to reinterpret the postcolonial condition of Latin America. “From the end of the decade of the 1870s onward, Marx never again abandons his thesis that the uneven development of capitalist accumulation displaces the center of the revolution from the countries of Western Europe to dependent and colonial countries,” writes Aricó. “We find ourselves before a true ‘shift’ in Marx’s thinking, which opens up a whole new perspective for the analysis of the conflicted problem of the relations between the class struggle and the national liberation struggle, that genuine punctum dolens in the entire history of the socialist movement.”9 Henceforth, Marx not only explicitly rejects the interpretation that would turn his analysis of capitalist development into a universal philosophy of history, applicable to any and all national situations; he also acknowledges the possibility that in so-called backward, dependent or colonial countries socialism may come about through a retrieval of pre-capitalist forms of communitarian production in superior conditions. If, in spite of this paradigm shift, provoked by his reflection on the supposed backwardness of cases such as Ireland or Russia, Marx is still unable to settle his accounts with Latin America by critically re-evaluating the revolutionary role of peripheral countries, this continued inability would be due, according to Aricó, to the stubborn persistence of Marx’s anti-Bonapartist bias and his unwitting fidelity to the legacy of Hegel’s theory of civil society and the state.

In his painstaking study of Marx’s complete oeuvre from the point of view of the national question in peripheral countries, On Hidden Demons and Revolutionary Moments: Marx and Social Revolution in the Extremities of the Capitalist Body, García Linera nevertheless raises two objections to Aricó’s interpretation. First, the Bolivian theorist accuses his Argentine comrade, exiled in Mexico, of proceeding too hastily to accept the absence of a massive or even national-popular capacity for rebellion in Latin America. According to García Linera, Marx himself never ceases to insist, against his allegedly regressive Hegelian baggage, on the importance of mass action, whereas Aricó would somehow be seduced by the autonomy of the political and the direct revolutionary potential of the state. The “blindness” or “incomprehension” of Marx toward Latin America, then, would be due to the lack of historical sources and reliable studies on the indigenous rebellions that had shaken the region since at least the end of the eighteenth century. “This is the decisive factor. In the characteristics of the masses in movement and as a force, their vitality, their national spirit, and so on, there lay the other components that Aricó does not take into account but that for Marx are the decisive ones for the national formation of the people,” affirms Linera. “There exists no known text from Marx in which he tackles this matter, but it is not difficult to suppose that this is because he did not find any at the time of his setting his eyes on America.”10 The missed encounter between Marx and Latin America, therefore, would be due not to the lingering presence of Hegelianisms so much as to the fact that “this energy of the masses did not come into being as a generalized movement (at least not in South America); it was for the most part absent in the years considered by Marx’s reflections.”11 In other words, it would be Aricó, not Marx, who misjudges the Latin American reality due to a blinding adherence to Hegel.

In fact, García Linera goes so far as to suggest that the supposed “not-seeing” on the part of Marx is the result of a “wanting-to-see” on the part of his most famous and prolific interpreter from Argentina: “The terrain on which Aricó places us is not that of the reality or that of Marx’s tools for understanding this reality, but rather the reality that Aricó believes it to be and the tools that Aricó believes to be those of Marx.”12 In the final analysis, however, even for García Linera it cannot be a matter of denying the unfortunate missed encounter, or desencuentro, between Marx and Latin America. To the contrary, in a recent lecture titled “Marxismo e indianismo” (“Marxism and Indigenism”), García Linera in turn speaks himself of a desencuentro between two revolutionary logics—the Marxist and the indigenist—before providing an overview of the different factors that hampered their finding a middle ground throughout most of the twentieth century, all the way to the tentative promise of a possible re-encounter among a small fraction of indigenous intellectuals in the last decade, especially in the Andean region: “Curiously, these small groups of critical Marxists with the utmost reflective care have come to accompany, register, and disseminate the new cycle of the indigenist horizon, inaugurating the possibility of a space of communication and mutual enrichment between indigenisms and Marxisms that will probably be the most important emancipatory concepts of society in twenty-first-century Bolivia.”13

Following Aricó’s example in the case of Marx, we could elaborate a similar critique of the missed encounter between Freud and Latin America. Georges Politzer, in his 1928 Critique of the Foundations of Psychology—a work that would take three-quarters of a century to be translated into English but that was widely read and discussed in Spanish-speaking countries—already tried to unmask some of these prejudices. Politzer thus criticizes Freud’s “fixism,” which tends to give his thought an idealist-metaphysical rather than a concrete-historical bent. As the Argentine psychoanalyst José Bleger concludes after giving an overview of Politzer’s writings on Freud,

We can observe two fundamental limitations: the first is that the key in the development of normal and pathological behavior turns out to be libidinal fixations and in this way the emphasis is put on the repetitive element, so that evolution becomes an epigenesis; the second limitation is a consequence of abstraction: to the extent that psychoanalytic theory becomes more abstract and replaces human realities with forces, entities, instances, the criterion of evolution becomes lost, in favor of a “fixism” of metaphysical allure.14

This might begin to account for some of Freud’s more glaring blindnesses with regard to the world outside of Western Europe, particularly the New World.

In fact, even if he saw himself as the Columbus of the unconscious, the founder of psychoanalysis never refers specifically to the realities of Latin America—at least not beyond his personal and anthropological interest in pre-Hispanic artifacts, and especially his fascination with the culture of the Bolivian coca leaf. There are, to be sure, a number of eyebrow-raising assertions similar to what Marx or Engels have to say early on about Mexicans, as when Freud refers metaphorically to the unconscious, in his paper of the same title from 1915, by speaking of the mind’s “aboriginal population”—or again, elsewhere, of the “dark continents.”15 And in Freud’s case, too, we could try to systematize the underlying prejudices, aside from a certain metaphysical fixity of concepts, which lead to such affirmations: the universalist trend of his interpretation of evolution, with identical stages for all of humanity; the correspondence between the phylogenetic and the ontogenetic aspects of development, which leads to the utilization of metaphors of primitivism above all with reference to neurosis and the early stages of infanthood, as in his 1913 text Totem and Taboo, significantly subtitled Some Points of Agreement between the Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics; and the Lamarckian faith in the possibility of the hereditary transmission of acquired traits, which likewise renders superfluous the study of other or earlier cultures beyond the confines of modern Western Europe. “These assumptions,” as Celia Brickman notes, “did not invalidate the potential of psychoanalysis, but their presence lent credence to readings of psychoanalysis that could perpetuate and seemingly legitimate colonialist representations of primitivity with their associated racist implications, in much the same way that psychoanalytic representations of femininity were able to be enlisted for some time as an ally in the subordination of women.”16

And yet, we might as well invert the conclusion to be drawn from Freud’s prejudices. The fixed, timeless, and phylogenetically inherited nature of the unconscious, even while being modeled upon evolutionary schemes of development from, and regression to, primitivism, could thus be read as a radical subversion of the superiority of the West: “Supposedly primitive behaviors were seen to lurk not only in the pathological and in the past, but in the everyday customs and in the great cultural institutions of modern European civilized public and private life,” Brickman is quick to add. “In the end, we are all more or less neurotic; we are all more or less primitive; we are all saurians among the horsetails.”17 Or, to make the same point in the words of Ana, the sickly artist-character from José Martí’s novel Lucía Jerez: “Of wild beasts I know two kinds: one dresses in skins, devours animals, and walks on claws; the other dresses in elegant suits, eats animals and souls, and walks with a walking stick or umbrella. We are nothing more than reformed beasts.”18 Similarly, Freud writes in The Interpretation of Dreams; “What once dominated waking life, when the mind was still young and incompetent, seems now to have been banished into the night—just as the primitive weapons, the bows and arrows, that have been abandoned by adult men, turn up once more in the nursery.”19 What we could infer from this, aside from a conventional gender portrayal, is the possibility of a truly revolutionary—rather than merely evolutionary—awakening of that which lies dormant in the present. This possibility resembles the way in which Marx imagines his task as a radical thinker in a letter to Arnold Ruge:

It will become evident that the world has long possessed the dream of something, of which it has only to be conscious in order to possess it in reality. It will become evident that it is not a question of drawing a great mental dividing line between past and future, but of realizing the thoughts of the past. Lastly, it will become evident that mankind begins no new work, but consciously brings its old work to completion.20

What is more, in Freud’s case, too, we come across an interesting paradox similar to Marx’s tardy discovery of the logic of uneven development. As the late Edward Said showed in his lecture Freud and the Non-European, not only might we expect Freud to have arrived at a critique of the ideological notion of primitivism, based on his own experience with the ideologies of racism and anti-Semitism in Europe which forced him to seek refuge in London and eventually brought him back for a visit to America—“Little do they know we are bringing them the plague,” Freud is famously said to have proclaimed when, just a little over 100 years ago he first disembarked, with Carl Jung and Sándor Ferenczi, in New York, perhaps still secretly comparing himself to Columbus, only now in terms of the discoverer’s epidemic effects. But, furthermore, the later so-called “social” or “culturalist” works of Freud, above all Group Psychology and Analysis of the Ego, Civilization and Its Discontents and Moses and Monotheism, also contain radical concepts of the structural lack of adaptation of the human species and the presence of a kernel of non-identity at the heart of every identity, including that of the Jewish faith, which could have brought the founding father of psychoanalysis to the point of questioning the effects of his own limited historicism and the temptations of Eurocentrism. “For Freud, writing and thinking in the mid-1930s, the actuality of the non-European was its constitutive presence as a sort of fissure in the figure of Moses—founder of Judaism, but an unreconstructed non-Jewish Egyptian none the less,” proposes Said. “Yahveh derived from Arabia, which was also non-Jewish and non-European.”21 Had he applied this radical principle of non-identity to other non-European cultures, our discoverer of the unconscious also could have had more than just a metaphorical connection to Latin America.

In addition to these missed encounters between Marx and Latin America, or between Freud and Latin America, we also have to take into account the obstacles that stand in the way of a proper articulation between Marx and Freud themselves. These are the obstacles that the various attempts at formulating some type or other of Freudo-Marxism have tried to overcome—to varying and, in the eyes of many, highly questionable degrees of success—from the earliest efforts by Wilhelm Reich and Otto Fenichel, via the parallel yet unfortunately non-synchronous tracks of the likes of Herbert Marcuse or Erich Fromm in the Frankfurt School in the 1950s and 1960s, and French thinkers such as Jean-François Lyotard, or the combination of Gilles Deleuze and Félix Guattari, who in the 1970s threw Nietzsche into the Marx-Freud mix, all the way to the recent work of someone like Slavoj Žižek who, rather than a Freudo-Marxist, would have to be considered a proponent of Lacano-Althusserianism by way of Hegel. In Latin America, though this too tends to be forgotten, there also exists a fascinating tradition in this regard—from the presence of Fromm in Mexico between 1950 and 1973 or the establishment of a psychoanalytical community between 1961 and 1964 in a Cuernavacan monastery by the soon-to-be-excommunicated Benedictine monk of Belgian origin, Gregorio Lemercier, via the collective project for a Freudian Left spearheaded throughout much of the region, from Uruguay to Argentina to Mexico, by the Jewish-Austrian exile Marie Langer (co-founder of the Argentine Psychoanalytical Association who described her own trajectory as a journey “from Vienna to Managua” under the Sandinistas), all the way to the Sartrean-inflected Lacanianism of Oscar Masotta in Argentina, or the Brazilian Suely Rolnik’s schizoanalytical collaborations with Guattari.22

Here, I should admit, we might be victims of amnesia to the second degree. Indeed, as I realized only recently, already in Social Amnesia: A Critique of Contemporary Psychology from Adler to Laing, the historian of Western Marxism Russell Jacoby ironically enough began with a critique of obsolescence that is strictly speaking identical to the one I am advocating here. “In the name of a new era past theory is declared honorable but feeble; one can lay aside Freud and Marx—or appreciate their limitations—and pick up the latest at the drive-in window of thought,” Jacoby writes, with great sarcasm: “The intensification of the drive for surplus value and profit accelerates the rate at which past goods are liquidated to make way for new goods; planned obsolescence is everywhere, from consumer goods to thinking to sexuality.”23 Nowhere does the dilemma posed by this obsolescence make itself felt more clearly than in the case of the debates surrounding attempts to amalgamate a certain Freudo-Marxism. The difficult task of articulation in this context consists in avoiding a purely external relation of complementarity between the social and the psychic, the collective and the individual, the political and the sexual. “The various efforts to interpret Marx and Freud have been plagued by reductionism: the inability to retain the tension between individual and society, psychology and political economy,” Jacoby remarks, before proposing what he calls a dialectical counter-articulation, inspired by the example of the Frankfurt School: “Critical theory does not know a sharp break between these two dimensions; they are neither rendered identical nor absolutely severed. In its pursuit of this dialectical relationship it has resisted the two forms of positivism that lose the tension: psychologism and sociologism.”24 Marxism and psychoanalysis can be articulated, in other words, only if the articulation at the same time retains the antagonistic kernel that defines the core of their respective discourses.

Through the critique of amnesia and oblivion, however, we should not come to overestimate the importance of memory either. History and memory, too, whether in personal memoires, nostalgic reminiscences, or public apostasies, have today become commodities that risk concealing more than they may be able to reveal. Nor should we ignore the recent past by resorting exclusively to the alleged orthodoxy of the founding texts of Marxism and psychoanalysis. “The critique of sham novelty and the planned obsolescence of thought cannot in turn flip the coin and claim that the old texts—be they of Marx or Freud—are as valid as when written and need no interpretation or rethinking,” warns Jacoby. “To the point that the theories of Marx and Freud were critiques of bourgeois civilization, orthodoxy entailed loyalty to these critiques; more exactly dialectical loyalty. Not repetition is called for but articulation and developments of concepts; and within Marxism—and to a degree within psychoanalysis—precisely against an Official Orthodoxy only too happy to freeze concepts into formulas.”25 Whence the need not just for remembrance to break the spell of amnesia, but also for a form of active forgetting to avoid the commodification, or what we might also call the becoming-culture, of memory.

As Gilles Deleuze posits in “Five Propositions on Psychoanalysis,” a text from 1973 included in the posthumous collection Desert Islands and Other Texts,

In the end, a Freudo-Marxist effort proceeds in general from a return to origins, or more specifically to the sacred texts: the sacred texts of Freud, the sacred texts of Marx. Our point of departure must be completely different: we return not to the sacred texts that must be, to a greater or lesser extent, interpreted, but to the situation as is, the situation of the bureaucratic apparatus in psychoanalysis, which is an effort to subvert these apparatuses.26

At the most fundamental level of our theoretical and quasi-ontological presuppositions, this means that the articulation of Freudianism with Marxism must proceed by undoing the developmental logic that would be common to both. Deleuze adds:

In Marxism, a certain culture of memory appeared right at the beginning; even revolutionary activity was supposed to proceed to this capitalization of the memory of social formations. It is, if one prefers, Marx’s Hegelian aspect, included in Das Kapital. In psychoanalysis, the culture of memory is even more apparent. Moreover, Marxism, like psychoanalysis, is shot through with a certain ideology of development: psychic development from a psychoanalytic point of view social development or even the development of production from a Marxist point of view.27

To deconstruct this ideology of memory and development, we might even be able to find an unexpected resource in the very notion of the missed encounter that is said to define the relation of Marx and Freud to Latin America.

Indeed, there is still a third perspective from which we might tackle our problem—namely, by taking the logic of the desencuentro itself as a key to understanding the emancipatory nature of the contributions made by Marxism and psychoanalysis and then using this key to approach the realities of Latin America. The founders of these discourses, to be sure, intended their work to be read as laying the foundation for new sciences, respectively, of history and of the unconscious. However, what these sciences at bottom encounter, despite their subsequent fixation and positivization, is something that does not belong to the realm of hard facts so much as it signals a symptomatic interruption of all factual normality:

Marx sets out, absolutely, not from the architecture of the social, deploying its assurance and its guarantee after the fact, but from the interpretation-interruption of a symptom of hysteria of the social: the uprisings and parties of the workers. Marx defines himself by listening to these symptoms according to a hypothesis of truth regarding politics, just as Freud listens to the hysteric according to a hypothesis regarding the truth of the subject.28

If Marxism and psychoanalysis can still be called scientific against all odds, it is not because of the objective delimitation of a specific and empirically verifiable instance or domain of the social order—political, psychic, or libidinal economies—but because they link a category of truth onto a delinking, an unbinding, or a coming-apart of the social bond in moments of acute crisis. Even if the new discourse he is commending does not amount to a philosophical worldview, Freud is quite explicit about the importance of the category of truth for psychoanalysis. “I have told you that psychoanalysis began as a method of treatment,” he tells his audience in his New Introductory Lectures on Psychoanalysis, “but I did not want to commend it to your interest as a method of treatment but on account of the truths it contains, on account of the information it gives us about what concerns human beings most of all—their own nature—and on account of the connections it discloses between the most different of their activities.”29 Freud immediately goes on to tackle the question about the problematic status of psychoanalysis as a worldview and as a science, before concluding, as is only to be expected, by engaging in a brief polemical dialogue with Marxism.

This dialogue is indeed to be expected, insofar as the notion of truth that both Marx and Freud can be said to uphold does not refer to a stable reality to be uncovered with the objectivity of a positive or empirical science, nor is the discourse for which they lay the foundation the result of a purely philosophical self-reflection. Rather, truth here is tied to a certain experience of the real that interrupts and breaks with the normal course of things. More so than as positive sciences or as philosophical worldviews, therefore, the discourses of Marx and Freud are better seen as doctrines of the intervening subject. “Even though psychoanalysis and Marxism have nothing to do with one another—the totality they would form is inconsistent—it is beyond doubt that Freud’s unconscious and Marx’s proletariat have the same epistemological status with regard to the break they introduce in the dominant conception of the subject,” Alain Badiou writes in Theory of the Subject: “‘Where’ is the unconscious? ‘Where’ is the proletariat? These questions have no chance of being solved either by an empirical designation or by the transparency of a reflection. They require the dry and enlightened labour of analysis and of politics. Enlightened and also organized, into concepts as much as into institutions.”30

The commonality between Marx and Freud, in other words, lies in their willingness and ability to propose the hypothesis of a universal truth of the political or desiring subject in answer to the crises of their time—whether these are the uprisings of the 1840s to which Marx and Engels respond in The Communist Manifesto with the hypothesis of an unheard-of proletarian capacity for politics, or the hysteric fits and outbursts that spread like wildfire through fin-de-siècle Vienna to which Freud responds with his hypothesis regarding the universality of a certain pathological subject of desire—as in his “Fragment of an Analysis of a Case of Hysteria,” better known as Dora’s case. A certain logic of the missed encounter, as structural-historical antagonism or as constitutive discontent, would thus be the ultimate “truth” about politics and desire that is the conceptual core of the respective doctrines of Marx and Freud.

These two figures, however, did not merely follow vaguely comparable or parallel tracks in the direction of a radical kernel of antagonism. Rather, the true insight behind the various attempts at amalgamating a form of Freudo-Marxism derives from the hypothesis that the questions of political, economic, and libidinal causality that the work of these two thinkers poses also mutually, yet without any neat symmetry, presuppose each other. As the Argentine León Rozitchner writes in Freud y el problema del poder (Freud and the Problem of Power), a book whose title should not hide the extent to which it puts Freudian psychoanalysis in dialogue both with Marxism and with the theory of war of Carl von Clausewitz,

I think that the problem at issue is the following: on one hand we have the development of state power since the French revolution to this day—whether capitalist or socialist—and, at the same time, the emergence of a power of the masses which with ever more vehemence and activism has begun to demand participation in it. This access gained by those who are distanced from power all the while being its foundation presents us with a need linked to the search for the possible efficacy as well as the explication of the failure in which many attempts to reach it culminated: the need to return to the subjective sources of that objective power formed, even in its collective grandeur, by individuals. Trying to understand this place, which is also individual, where that collective power continues somehow to generate itself and at the same time—as is all too clear—to inhibit itself in its development. In short: What is the significance of the so-called “subjective” conditions in the development of collective processes that tend toward a radical transformation of social reality? Is the condition of radicality not determined precisely by deepening this repercussion of the so-called “objective” conditions in subjectivity, without which politics is bound to remain ineffective?31

Such would be, in the broadest possible terms, the long-term presuppositions that undergird the search for an articulation between psychoanalysis and Marxism.

After all, as Rozitchner also observes, Marx had already pointed out this unity of the subjective and the objective, as opposed to the usual opposition between the “merely” internal and the “merely” external. Especially in the notebooks from 1857–58 known as the Grundrisse: Foundations of the Critique of Political Economy, speaking of the objectification of labor, which turns individuals immediately into social beings, Marx writes: “The conditions which allow them to exist in this way in the reproduction of their life, in their life’s process, have been posited only by the historic economic process itself; both the objective and the subjective conditions, which are only the two distinct forms of the same conditions.”32 Conversely, in Group Psychology and Analysis of the Ego, Freud famously starts out by insisting that to speak of a social psychology is perhaps more redundant than truly insightful, insofar as the unconscious is always already socialized through and through: “In the individual’s mental life someone else is invariably involved, as a model, as an object, as a helper, as an opponent; and so from the very first individual psychology, in this extended but entirely justifiable sense of the words, is at the same time social psychology as well.”33 This also means that power and repression are not simply external to the subject; instead, they feed on what we otherwise consider to be our innermost idiosyncrasy. For Rozitchner, this paradox of the subjective inscription of power is ultimately what psychoanalysis, as an intervening doctrine which is not restricted to the therapeutic space of the couch in the consultation room, strives to uncover: “It is the emergence, beyond censorship and repression, of significations, lived experiences, feelings, thoughts, relations, drives, etc., present in our subjectivity, very often without their having reached consciousness, but actualized in objective relations, which break with that stark opposition that the system has organized in ourselves as though it were—as in some way it is—our own.”34

Of course, this relation of mutual presupposition between the psychic-libidinal and the politico-economic should not serve to hide the profound asymmetries between the two. Marxism and psychoanalysis do not simply complement each other by filling the gap in their neighbor’s discourse. Nor should the invocation of what Freud calls overdetermination, as a feature supposed to be common to both fields, lead us to ignore the shifting priorities variously given to one instance or the other—the socio-historical or the psychic—by the different followers of Marx and Freud. Indeed, the question of knowing which would be determining in the final instance is still open, and the chapters that follow certainly do not claim to answer this question definitively. The aim is rather to dwell on the tensions of the struggle between the subjective and the objective, between the psychic and the historical, precisely as struggle, as combat and as transaction. “Transaction: objective-subjective elaboration of an agreement, the result of a prior struggle, of a combat in which the one who will become subject, that is, the I or the ego, is not that sweet angelical being called child, such as the adult imagines it, which would come to be molded with impunity by the system without resistance,” Rozitchner insists. “If there is transaction, if the I is its locus, there was a struggle at the origin of individuality: there were winners and losers, and the formation of the subject is the description of this process.”35 Indeed, it is with an eye on studying the intricacies of such a struggle that I turn in the following pages to a small corpus of texts and artworks from Latin America.

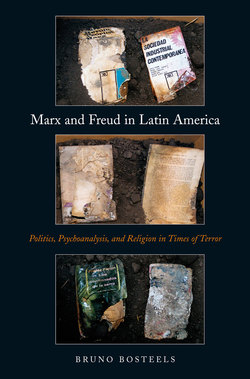

More so than as a work of commemoration, not to mention nostalgia, I envision the studies that follow as exercises in a kind of counter-memory, not unlike the installation The Wretched of the Earth from the Argentine photographer Marcelo Brodsky. This installation includes a series of books that its owner—like so many students and intellectuals in the mid-1970s when the military junta in Argentina considered all such books potential proof of subversive activity that could lead to imprisonment, torture, and death—decided to bury in her backyard, where almost twenty years later they were dug up by her two adult children. Although time and the elements have eaten away at the books to the point of making them nearly unrecognizable, most readers familiar with the literature from the period will be able to discern that among the books on display in Brodsky’s installation are Spanish translations of Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth (Los condenados de la tierra), Louis Althusser’s For Marx (La revolución teórica de Marx), a collection of essays by Erich Fromm, Herbert Marcuse, André Gorz, and Víctor Olea Franco (La sociedad industrial contemporánea), as well as a totally disheveled and nearly coverless copy of Materialismo histórico y materialismo dialéctico (Historical Materialism and Dialectical Materialism), with texts by Althusser and Badiou, published in the book series Pasado y Presente edited by José Aricó. In a handwritten letter accompanying the installation, the original owner explains that, since she no longer remembered where exactly she had buried the books, her two sons had to dig several holes over the course of four days before finding the “treasure.” She adds: “The screams of joy from our kids contrasted sharply with the image of the destroyed books and everything they represented.”36

Much of what I hope to do with the studies included in the present book can be said to consist in an effort to dig similar holes and tell the story of what happened with those works and others like them that were censored, forgotten, buried, or destroyed since the mid-1970s, in sharp contrast to the time in the late 1960s and early 1970s when many of them still represented obligatory reading materials for students, writers, intellectuals, militants, and artists alike. This effort in constructing an archive of counter-memory concerns not only the books that were actually buried and, in some cases, disinterred: what happened, for example, between the coup of 1976 in Argentina, when the books listed above were abandoned to the criticism of worms, and the supposed return to democracy during which, in 1994, they were brought back into broad daylight and exhibited to the public? Counter-memory also concerns the ideas, dreams and projects that were otherwise forced to find a more figurative hiding place in the inner recesses of the psychic apparatus of their original readers and proponents.

The questions that I have in mind are similar to the ones that León Rozitchner asks of Óscar del Barco, for instance, regarding the long period of silence that separates his recent epistolary confession in “Thou Shalt Not Kill” from the historical acts of violence for which—forty years later—he offers his loud mea culpa. “Are we sure that one can pass, just like that, from one theory to another, from one concept to another?” asks Rozitchner. “So then what happened to our body, to our imagination, to our affects?”37 Del Barco may well have found a way to abandon Che Guevara’s deadly model of guerrilla warfare in favor of a post-metaphysical ethics of respect for the other inspired by Emmanuel Levinas. Yet he does not touch upon the subjective roots—both psychical and corporeal—of this seemingly purely theoretical shift. Nor does he clarify the personal coherence, or lack thereof, behind the decisions of those who were militants then and are anti-militants now. “But beyond the act of personal contrition that allows them to put their lives back together, what really matters, for us, is that these facts, which they did not assume, remained congealed like hard cores, or black holes, in the collective consciousness. They determined the past which for us is this future—the future past—that we are living today.”38 What remains in the shadows thus involves the motives, illusions, dreams and misprisions by which the subject becomes part of a historical truth that is still in the making. Where did the guilt, the shame, the anxiety, the rage, the pain, or the fear of death go to hide during all those years—before erupting into a loud confession that revolves around a Judeo-Christian commandment? In part following Rozitchner’s approach, the point of the exercises of genealogical counter-memory that I am proposing here is not to retrieve such subjective elements by inserting them into a nostalgic re-objectification of the past, but rather to reactivate their silent and still untapped resources for the sake of a critique of the present. “If at the time one had assumed as a social responsibility that which later underwent a metamorphosis and became a purely individual guilt,” Rozitchner continues, “one might have permitted the creation of something which fashionable thinking today calls an event, and thus the creation of a new meaning that would vanquish the determinism that marked us all.”39 Along these lines, incidentally, what in European theory and philosophy is called an “event” or “act” will also receive a rather different—frequently polemical—interpretation thanks to the confrontation with the conceptual trajectories behind similar notions in Latin America.

Given this critical and theoretical orientation, my project is only indirectly related to the many “left turns” in the recent political history of Latin America, where at he start of 2010 we had democratically elected center-left, left-populist, or self-proclaimed socialist governments in power in at least eleven countries. “Two centuries after the wars of independence, one century after the Mexican Revolution, half a century after the Cuban Revolution, the new mole has re-emerged spectacularly in the continent of José Martí, Bolívar, Sandino, Farabundo Martí, Mariátegui, Fidel, Che and Allende,” writes Emir Sader, borrowing the famous mole-metaphor from Hegel and Marx. “It has taken on new forms in order to continue the centuries-old struggle for emancipation of the peoples of Latin America and the Caribbean.”40 This circumstance, which constitutes the favorite topic for sociologists and political scientists writing about Latin America today, certainly contributes to the recent resurgence of interest in the intellectual and ideological debates of the 1960s and 1970s. Testimonies and anthologies thus proliferate, as do the often state-sponsored facsimile republication of books and even entire runs of left-wing journals. For the most part, though, the rich documentary and testimonial literature that has come out of the different left turns has yet to produce an equivalent intensification in the overall critical analysis and theoretical elaboration of Marxism and psychoanalysis in Latin America—a collective project to which I hope to make a small contribution in the case studies that follow.

The present book thus seeks to reassess the untimely relevance of certain aspects of the work of Marx (but also of Lenin and Mao) and Freud (but also of Lacan) in and for Latin America, with select case studies drawn from Mexico, Argentina, Chile, and Cuba. Starting from the abovementioned premise that Marxism and Freudianism strictly speaking are neither philosophical worldviews nor positive sciences, but rather intervening doctrines of the subject respectively in political and clinical-affective situations, I argue in the chapters of the book that art and literature—the novel, poetry, theater, film—no less than the militant tract or the theoretical treatise, provide symptomatic sites for the investigation of such processes of subjectivization. I will discuss almost none of the major recognized figures behind the various Communist (Marxist-Leninist, Trotskyist, Guevarist, Maoist) parties in Latin America—such as Julio Antonio Mella in Cuba, José Carlos Mariátegui and Víctor Raúl Haya de la Torre in Peru, Farabundo Martí and Roque Dalton in El Salvador, Vicente Lombardo Toledano in Mexico, René Zavaleta Mercado and Guillermo Lora in Bolivia, Marta Harnecker in Chile, Cuba and Venezuela, Luis Carlos Prestes or Caio Prado Júnior in Brazil, Luis Emilio Recabarren or Salvador Allende in Chile, Rodney Arismendi in Uruguay, or Aníbal Ponce and Otto Vargas in Argentina.41 Nor do I have any pretension—or the wherewithal—to retell the official history of the different national affiliates of the International Psychoanalytical Association (IPA), many of which are gathered in overarching organizations such as the FEPAL, or Federación Psicoanalítica de América Latina (Psychoanalytic Federation of Latin America, formerly known as COPAL, or Coordinating Committee of Psychoanalytic Organizations of Latin America).42 My justification for not taking this canonical route is twofold: first, because large parts of the history of the reception of Marx and Freud in their national and institutional venues have already been published; and, second, because the heretical treatments of Marxism and Freudianism in literary, artistic, and critical-theoretical form are often far more acutely aware of the shortcomings and the as-yet-untapped resources of Marx and Freud in and for Latin America. Besides, I might add that, just as I do not discuss any of the major intellectuals of the different Internationals linked to the legacies of Marx and Freud, so too most of the figures discussed in this book are absent from the extant histories of the reception of Marxism and psychoanalysis in Latin America—the principal exception in this last regard being the Cuban writer and freedom fighter José Martí.

To be sure, not all ten chapters of this book combine, or even seek to combine, equal parts from both Marxism and psychoanalysis. None aim to refer the works under discussion either to some prior orthodoxy or to some longed-for univocity based on these two discourses. Some chapters even discuss texts such as a series of pulp-fiction detective novels that may appear at first sight to be only remotely related to the topic of Marx and Freud in Latin America. In each case, however, I attempt to tease out a theoretical framework from the texts themselves, to the point where an author who is the object of analysis in one chapter can become the methodological reference point with which to analyze the objects of study in another. In fact, if there exists a standard against which I would like this book to be measured, aside from a penchant to go against the grain of accepted readings, it would be the idea of breaking down the traditional lines of demarcation between object and subject, criticism and theory, or literature and philosophy. Marxism and psychoanalysis, in this sense, serve as jumping-off points toward a renewed understanding of what I would gladly call “critical theory”—an intellectual practice for which criticism is not simply an ancillary qualification of theory but instead refers back to the specific tasks of close reading, as in literary or film criticism.43 Finally, at key points in this book and again at the very end, politics and psychoanalysis enter into dialogue with religion not only by way of a historical critique of Christianity or of the role of liberation theology in Latin America, but also through a brief return to “On the Jewish Question”—that is, to Marx’s text, as well as to some of the broader issues surrounding the question of religion whereof echoes can still be heard in the many writings by and on Freud such as The Future of an Illusion.

There is yet a third reason why I sidestep all discussion of the orthodox traditions of Marxism and Freudianism in Latin America—namely that, chronologically speaking, all the works analyzed in this book (again with the exception of José Martí’s writings) belong to a period in the latter half of the twentieth century marked by the internal crisis and critique of orthodox Marxism, and a concomitant revision of, and critical return to, Freud. If Martí is part of this book, it is because his chronicle on the occasion of Karl Marx’s death on March 14, 1883, especially when read in conjunction with Martí’s only novel, his 1885 Lucía Jerez (also known as Amistad funesta), anticipates a number of principles—in particular the logic of uneven development and the melodramatic responses that this logic often seems to elicit—that will recur in subsequent articulations of culture, politics, and psychoanalysis in the second half of the twentieth century, when we gradually cross beyond a post-revolutionary horizon. The events of 1968 clearly mark a threshold along this trajectory, and their influence can therefore be felt throughout the book. Thus, José Revueltas, thrown in jail by the government of President Gustavo Díaz Ordaz for his alleged role as intellectual instigator behind the revolt of this watershed year in Mexico, constitutes one of the book’s central theoretical reference points, together with the work of the Argentine Freudo-Marxist León Rozitchner. More specifically, Revueltas’s 1964 novel Los errores (The Errors) and his posthumous Dialéctica de la conciencia (Dialectic of Consciousness), written in the 1970s in the Lecumberri prison, are analyzed in Chapters 2 and 3 in terms of a critique of Stalinism and the ethico-theoretical revision of Marxism. Together with a little book by Paco Ignacio Taibo II, Revueltas’s interpretation of the events of 1968 is also read in Chapter 6 as a counterpoint to Octavio Paz’s poem about the massacre that took place in Tlatelolco on October 2, 1968—a poem that Paz sent to the cultural supplement of the magazine Siempre! right after the massacre, while at the same time submitting his resignation as the ambassador for Mexico in India to President Díaz Ordaz. Rozitchner’s little-known book Moral burguesa y revolución (Bourgeois Morality and Revolution), on the other hand, provides an important subtext for the Cuban filmmaker Tomás Gutiérrez Alea’s 1968 movie Memorias del subdesarrollo (Memories of Underdevelopment), which I study in Chapter 4 in conjunction with Gutiérrez Alea’s own Dialéctica del espectador (The Viewer’s Dialectic). Rozitchner’s work in Freudo-Marxism in general, and his critique of Christianity in particular through the reading of Augustine’s Confessions in his 1997 book La Cosa y la Cruz (The Thing and the Cross), constitutes the topic of Chapter 5.

Subsequent chapters, by contrast, inquire into the melancholy paths of the post-1968 Left. Chapter 7 provides an analysis of the Maoist legacy in the writings of the Argentine novelist and critic Ricardo Piglia, especially his 1975 novella “Homenaje a Roberto Arlt” (“Homage to Roberto Arlt”), included in Nombre falso (Assumed Name). This analysis leads to a critique of the political economy of traditional concepts of art and literature that persist even within the revolutionary Left, from Bakunin to Lenin to Trotsky. In Chapter 8, I read the play Feliz nuevo siglo Doktor Freud (Happy New Century, Dr Freud), which the Mexican playwright Sabina Berman in 2000 devoted to a reworking of Freud’s famous Dora case, in light of the question of cultural democratization and the emancipatory potential of psychoanalysis. In Chapter 9, the series of nine novels (ten if we include Muertos incómodos, or The Uncomfortable Dead, coauthored with Subcomandante Marcos from the EZLN or Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional) that, between 1976 and 1993, Paco Ignacio Taibo II structured around his hardboiled detective Héctor Belascoarán Shayne, are interpreted as contributions to a narrative history of the Left in Mexico. In Chapter 10, through an analysis of the novels Plata quemada (Money to Burn) by Ricardo Piglia and Mano de obra (Labor Power or Manual Labor) by the Chilean Diamela Eltit, I discuss the recurrent temptation of seeking a radical anarchistic alternative, often figured as the gift of a giant potlatch, to the crisis of neoliberalism and the formation of that new world order which Michael Hardt and Antonio Negri famously describe as Empire in their book of the same title—a book which was widely circulated and debated in the Southern Cone, especially around the time of the economic crisis of December 2001 in Argentina. Finally, the Epilogue revisits a question that runs through each of the previous chapters as seen in particular through the twin matrices of melodrama and the crime story—namely, the shifting relationship of hierarchy between ethics and politics that resulted from the moralization of political militancy among the post-1968 Left.