Читать книгу Broken Doll - Burl Barer - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеChapter 1

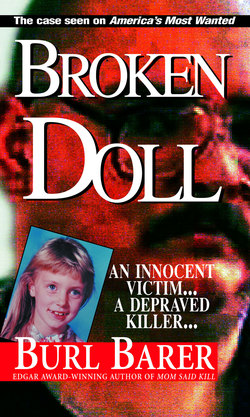

On the final night of her life, Roxanne Doll spent the hour before bedtime watching a Disney video with her mother, sister, and brother. It was Cinderella, the fairy-tale romance about castles, glass slippers, and an adorable, exploitable young girl rescued by love and magic from a life of mistreatment and toil. Roxanne didn’t live to see sunrise.

Sometime during the night, she was abducted from her bed, raped, and stabbed to death. Her body was found on April 8, 1995, dumped down a brushy north Everett hillside. The blond-haired, blue-eyed second grader lay there for a week, partially buried under a heap of grass clippings and other yard debris.

Roxanne’s disappearance and death struck a nerve in Snohomish County. Hundreds of people beat the brush around south Everett looking for the missing child near her home. When her body was found, hundreds more openly mourned her. Family, friends, and strangers wept at the funeral—a funeral that her parents, on their own, could ill afford.

“If it wasn’t for some very wonderful strangers,” said Roxanne’s mother, Gail Doll, “Roxanne’s funeral would have been nearly impossible to do. So many people gave to us so we could bury her with more dignity and the respect she deserved.” A makeshift roadside shrine was erected where two children picking berries discovered her body.

The man arrested, charged, and convicted of this most heinous crime was no stranger to Roxanne Doll or Feather Rahier. According to the newspaper, the twenty-six-year-old suspect lived in a garage on Lombard Street. His name was Richard M. Clark.

Snohomish County prosecutors, seeing similarities between the 1988 incident involving Feather and the 1995 kidnapping/murder of Roxanne Doll, subpoenaed Feather in February 1997. “When it was opened and she read it, she became very angry,” recalled Gelo.

“I refuse, I’ll not testify. I don’t want to be in the courtroom,” Feather said. “I don’t want to remember what happened to me.”

Clark’s defense attorneys also wanted a deposition, which she reluctantly provided that very month. During the deposition, Feather repeatedly deflected questions by saying, “I don’t remember.” In truth, she remembered.

“I knew Feather had disclosed things to me that would have answered some of those questions,” recalled Gelo. “And so I asked her, I said, you didn’t tell him everything, did you? She hung her head and kind of got tears in her eyes. She said, ‘No, I didn’t. I could have answered just about all of his questions, but I don’t want to remember. I get so scared and I get so sad that I’m afraid of what I might do, and what others might do. I just don’t want to think about it; I don’t want to talk about it.’”

Feather’s anger and resentment soon influenced all aspects of her life. “I started getting telephone calls from her school,” recalled Gelo. “They told me that she was losing control in the classrooms, yelling at the teachers, saying that she had to get out of the classroom, that she felt she was being closed in. Then, on Sunday, February twenty-third, she lost control at our house and threatened to hurt herself or to kill herself, and to hurt another child in my home. She ran away, going out her bedroom window.”

The police found Feather fifteen miles away—she had walked the entire distance. When Gelo arrived at the Everett Police Department, Feather was in handcuffs because she was still threatening to hurt herself or hurt others.

“At this point,” said Gelo, “it was decided to take her to Everett General Hospital. She was released from handcuffs for a while at the hospital and she took a paper clip and was trying to carve in her arm. Two mental-health professionals evaluated her at the hospital that night, and had her transported by ambulance to the Fairfax Psychiatric Hospital in Kirkland, Washington, arriving about five in the morning on Monday the twenty-fourth.”

Gelo took Feather to Harborview Hospital for an involuntary-commitment hearing, requesting that the youngster be held for fourteen days for a complete psychiatric evaluation. The involuntary-commitment order was declined, Gelo explained, because “Despite Feather’s threats, there had never been any actual harm done to another child in my home, and because the scratching and the carving on her arm had not drawn blood.”

The Department of Social and Health Services decided that it would not be safe for Feather to return to Gelo’s home until there were other services in place to make sure she would not carry through with her threats.

“At that point, she was placed in a facility called Cedar House from Tuesday, the twenty-fifth of February, until Monday, March third,” said Gelo. “I had numerous contacts with her while in Cedar House, and we worked on things such as family reconciliation, and we worked on getting additional services in place to make it possible for Feather to return to my home, which she did on March third.”

Feather returned under close supervision and heavy medication, including twenty milligrams of Prozac, one milligram of Klonopin, and forty milligrams of Ritalin. Near comatose from Klonopin, she sleepwalked through school on Tuesday, March 4, before that medication was removed from her regimen.

“We also had, in addition to once-a-week group therapy sessions, a case manager and outreach worker appointed for her by LifeNet Mental Health,” Gelo said. “We had no-harm contracts drawn up between Feather and our household and a crisis-intervention plan was set into place. And with that, she seemed to level off for a little while.”

Tuesday, March 11, Feather came home after a session with the outreach worker and told Gelo that she had something to show her. “She took me into the kitchen and showed me that on the inside of her right ankle that she had started to carve initials, initials of a boy. These actually were cut into the skin,” Gelo recalled. “It was not a scratch, and it was an actual cut done by a razor blade. We then put into place more precautions at home, locking up all knives, even dinner knives and kitchen knives, taking away all mirrors, everything that we could find that could be potentially dangerous.”

The following day, March 12, deputy prosecutor Ronald Doersch sent Feather a fax via Lori Vanderberg at LifeNet Health. The transmission contained an avalanche of embarrassing and troubling questions.

Doersch requested the girl’s recollection of how often she was touched, what she felt, what it felt like, what he said before, during and after she was tied up, where she was touched after being tied up, and what parts of Richard Clark’s body touched her body. He also asked if Richard touched himself while touching her, and what parts of his body were touched, why and when he stopped touching her, what he did after the touching stopped, and if Richard Clark told her not to tell anyone, or he threatened her in any way.

“Thank you in advance for your cooperation in this matter,” wrote Doersch. “We realize how difficult this is for you.” It was more difficult than Doersch knew.

“She completely lost her appetite,” recalled Gelo. “She was now down to ninety-eight pounds and was being monitored twice a week by the pediatrician because we were really concerned about her weight loss and her not wanting to eat.”

A few days after receiving Doersch’s fax, Feather requested adoption by Gelo and her husband. “She wanted to be able to use our last name, that she wanted to know that she was going to be safe and in our home forever, and not ever have to leave.”

The desire for adoption did not spring fully grown from Feather’s heart in a sudden burst of inspiration. Adoption was an ongoing topic at Gelo’s, and Feather witnessed the process firsthand. Gelo took Feather’s request seriously, advising her to discuss it with her court-appointed guardian.

“Gelo’s remarkable sensitivity to Feather’s personal issues,” said a woman familiar with Gelo’s unquestioned dedication to those in her charge, “is well known in the foster-care community. Gelo’s own life, and personal challenges, are not only inspirational, but mirror in many ways those of her troubled foster children.”

Born and raised in a North Dakota alcoholic home, Gelo was drinking out of her dad’s beer bottles as early as she can remember. Her first major drunk was at thirteen. At fourteen, she met her first husband. He was nineteen and on his way to Vietnam for his first of two tours of duty.

Gelo was always with kids older than herself, and by age sixteen, she was spending most of her free time on the college campus drinking three to four nights a week. When her husband came home after two years in Vietnam, his drinking fit right in with her alcohol-based lifestyle. They partied every weekend, said Gelo, and she did “controlled” drinking a couple of times during the week.

Pregnant at seventeen, she denied the condition until almost her sixth month, and kept up her drinking lifestyle. Two days after Gelo’s eighteenth birthday, her first child was born. A daughter, Faith, was only six pounds twelve ounces, and eighteen inches long. All through school and with the subsequent birth of two more children, Gelo realized that Faith was different. She struggled in school and with relationships, but she graduated from high school at nineteen without much special help from the schools.

Gelo stopped drinking when Faith was eight years old, divorced her first husband, and married again five years later to another alcoholic, but one who was in recovery. Moving to Washington State, they became foster parents. Nothing prepared them, however, for the difficulties of their first foster children. One day her second daughter came home from high school and told her about Linda LaFever, a woman from whom she heard about fetal alcohol spectrum disorders. Fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol effect (FAS/FAE) are disorders of the brain resulting from exposure to alcohol while in the mother’s womb. FAS is the most severe form; FAE, although not as physically visible in its outward signs, has equally serious behavioral impact. LaFever’s son, Danny, was seriously affected by her drinking during pregnancy.

The most serious characteristics of FAS/FAE are the invisible symptoms of neurological damage, including mental illness, disrupted school experience, incarceration, alcohol/drug abuse, and inappropriate sexual behavior. Almost half of individuals with FAS/FAE between the ages of twelve to twenty commit crimes against persons, such as theft, burglary, assault, murder, domestic violence, running away, and child molestation.

Gelo’s young foster children manifested many traits symptomatic of FAS. They were all obstinate and defiant, failed to bond with anyone, had no sense of personal boundaries, and did self-injurious things. Gelo had her two foster boys diagnosed; both had FAS. Faith, Gelo’s firstborn child, was also affected.

Feather Rahier was part of the Gelo household in July 1996 when the Gelos adopted two of their foster children, a boy and a girl. The boy was diagnosed with atypical FAS and his sister with neurobehavioral disorder—alcohol and cocaine exposed. They both had a diagnosis of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). The young boy also had reactive attachment disorder, oppositional defiance, and conduct disorder. The female had post-traumatic stress disorder, separation anxiety, and depression.

Soon another child, a boy, was added to the mix. A succession of other foster children came and went before the boy’s brother came to live with the Gelos. Two years later, another brother joined the family—a delicate child afflicted with febrile seizures. During the course of getting a CAT scan for the seizures, it was found that he had diffuse atrophy through his entire brain. There was a hole in the left temporal lobe attributed to alcohol exposure.

In June 1995, one month after Feather Rahier moved in, Gelo received a call from a caseworker asking her to take a ten-day-old baby who had been a full-term breech delivery on the streets of Seattle, but the infant only weighed a little over five pounds. He almost suffocated at birth, and tested positive for syphilis. Fetal alcohol syndrome was strongly suspected.

When the child was three months old, a neurologist said that the boy would always be severely retarded. “He may never roll over or even respond to people,” reported the specialist. Other doctors speculated that he would not live a full year. “He did not sit up alone until eleven months,” recalled Gelo. “He crawled at thirteen months, walked with an orthopedic walker at twenty-two months, and on his second birthday took his first independent steps. He survived and thrived, although his mother didn’t.”

Shortly after requesting that her parental rights be terminated so the child could be adopted by “the only mom and dad he has ever known,” her drinking and drugging took their toll. She had cirrhosis, meningitis, hepatitis, renal failure, sepsis, and had been assaulted and beaten at a party. After two weeks in a coma and on a respirator, she woke up, looked at Julie Gelo and the pictures of her children, and passed on. “She was twenty-eight years old at her death, and both her parents died in their early thirties from alcohol,” recalled Gelo. The adoption was completed in October 1995.

Illumed by the above history, Feather Rahier’s request for adoption by Gelo would appear both logical and prudent. Seeking outward stability as an anchor for inward instability, Feather sought a situation of inclusive permanence.

Sadly, there was nothing permanent in Feather’s immediate future, least of all her own moods. Troubled and volatile, Feather was often found crying in her closet. “The next minute, she could be exploding in anger,” said Gelo. “It was very hard on her and on the rest of our family.”

The youngster’s pediatrician wrote to the prosecutor’s office asking, if possible, that Feather be excused from having to testify. “He felt that all of this was having a real negative impact on her mental health,” said Gelo. “He was afraid that we would end up losing her totally.”

Gelo repeatedly assured Feather that everyone was doing everything in his or her power to keep everything as easy, nontraumatic, and safe for her as possible. These assurances failed to calm Feather’s fears.

“I would go in to check on her at night, and sometimes she would be thrashing around in her sleep. If I went to lay my hand on her shoulder, and went to talk with her and say, ‘Feather, it’s okay,’ she would kind of thrash at me with her hands and say, ‘Don’t touch me, don’t touch me, leave me alone.’”

Feather’s behavior became more troublesome as the date of Clark’s trial grew closer. “She was attempting to draw attention to herself or cry out for help in some ways,” said Gelo. “She would come and tell me what she was doing and they were behaviors that she knew would get consequences, or knew would get attention, you know, from me and from the other people in her life. And it was things like accepting a bottle of cider from a winery down the hill from us that had alcohol in it and drinking part of that bottle, but bringing the rest of it home and giving it to me.”

Feather also wore very provocative clothing to school—outfits that were not provocative when first purchased. “She was taking all of the new clothing that we had bought her and cutting it up and making it very sexualized—cutting, you know, the pants to be very short, or the T-shirt, so that they would expose her midriff,” Gelo said. “That isn’t what she would leave the house in the morning with, but she would carry these clothes in her backpack and change. And I would get calls from the school asking that I bring her more appropriate clothing.”

One day, Feather vanished from school after first period. Students and teachers overheard her say that she was leaving with two boys. “The story was that they were going to a boy’s house,” Gelo recalled, “because the boys wanted to do drugs. Feather wanted to go along to do her ‘wild thing’ that day. She was back in school by the beginning of fourth hour, and didn’t appear intoxicated or under the influence of drugs. Feather knew that when she got home, she would be getting consequences at home, and yet she came home straight off the bus.”

Advised by Gelo that skipping class was not a prudent decision, and one that entailed consequences, Feather had no objections. “She was not the least defiant,” said Gelo. “She was pleasant and cooperative.”

Spring break started that day, and Feather was put on restriction. “Again, there was no arguing, not even the sullen look that I would have seen from any of my other teenagers. Saturday morning, she got up very compliant, asked me, ‘What can I do to help you today?’”

Feather helped with the children while Gelo went grocery shopping. “She asked if she could go outside and rollerblade, and my husband said it was okay as long as she was on the corner of our house, and not across the street. That was fine with Feather, it seemed. She soon returned, and my husband suggested that they go downstairs and watch a movie together. He went on down and waited for her, but she didn’t come down.”

He looked upstairs, and out on the deck, but Feather wasn’t there. “He looked out the living-room window just in time to see her rollerblading by our house with a backpack on her back and a little bag in her hand. And a few minutes later,” said Gelo, “my nineteen-year-old daughter, Faith, came to our house and she had seen Feather down at the 7-Eleven with what looked like a cigarette in her hand. By that time, I had come home, and we went down looking for her and she was gone; we couldn’t find her. And,” said Julie Gelo, in 1997, “that’s the last time anyone has seen or heard from her.”

Rather than again relive her childhood trauma, Feather packed basic belongings into a backpack, then rollerbladed down the block, around the corner, and out of sight.

She would never be a witness for the prosecution against the man charged in the brutal, sexually motivated slaying of seven-year-old Roxanne Doll—the big man from the dark garage whose fractured family, abusive upbringing, and interpersonal malaise were tragically similar to her own—a young man who manifested each stereotypical trait of the fetal alcohol spectrum disorders: Richard Mathew Clark.