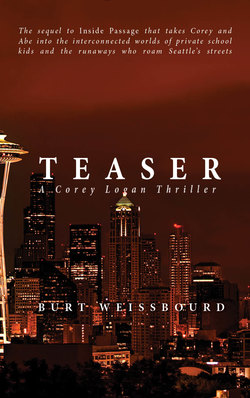

Читать книгу Teaser - Burt Weissbourd - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER ONE

Corey Logan was online, checking out VampireFreaks.com/Gothic Industrial Culture. One of the kids she was looking for was a “Goth,” and Corey was trying to figure out just what that meant. She was reading about New Orleans, the vampire and voodoo mecca of America.

She turned away from her screen, setting her boots on the window sill. Through her window she could see a Japanese container ship slowly bearing down the shipping lane past downtown Seattle.

Corey could just shut down her lovely face, make it hard and lifeless. When she didn’t, her face was like some kind of barometer, giving an instant reading of whatever was brewing inside. At the moment she was thinking, on the edge of something. The corners of her mouth had turned up, just a little; the fine lines around her pale grey eyes had disappeared, and the patch of freckles that spread across her nose had crept onto the gentle rise of her cheeks. She relaxed when she was thinking. She just liked it. Her husband, Abe, guessed it was her time in prison. Corey thought it began earlier, during the long days at sea. Her smile, when it came, was open and warm.

Her boots shifted as she tilted her head back, and the scar running from her ear to her collarbone made a thin pink line. Corey was thinking about her son, Billy. When she’d called earlier Billy was upstairs, “getting it together,” an expression, she’d discovered, that covered almost any activity. She imagined him at his computer, checking out some edgy web site, listening to music, and texting his friends.

On the phone, she and Billy had worked out the timing and the driving for his school’s eleventh-grade family night dinner. It was a potluck, which Corey hated because it meant she had to bring something that other people would eat. Last time she’d come empty-handed, and a mother from the parent organization had explained to her that “potluck” was a Native American word for sharing.

The buzzer was too loud, and unexpected. Corey went through the empty reception area. The half glass door said: Corey Logan, in big block letters. On the glass she saw a woman’s shadow. The buzzer rang again. Who was that?

“Coming,” she called to the silhouette on the glass, then she opened the door. In the hall a skinny, teenage girl was staring at the floor, using her middle finger to twist a knot in her flaming red hair. She wore over-sized black sunglasses. “Annie, what…?”

Annie toed the hardwood floor.

“Come in.”

Annie sat down, took off her sunglasses. There were cuts on her hands, forearms, neck, and face, and sticky mats of blood in her hair. One of her eyes was blackened. “He found me,” the girl said.

“Luther?”

When Annie nodded, ever so slightly, Corey felt pressure inside, like she was overheating. Her skin was cold though, clammy. She sat beside Annie, taking her hand. Corey was a detective who was hired out exclusively to find runaways—on one condition: once found, the runaway became the client. And once found, Corey worked with these young people to make sound decisions about their lives. Usually, they had a reason to leave home, and though returning home was always an option they considered, it was not necessarily the goal.

Annie liked living with her mom when her uncle wasn’t around. But she couldn’t live there if he was stopping by. So she ran away ten days before Uncle Luther was released from prison. When Corey found Annie, four weeks later, she checked in with Luther’s Community Corrections Officer (CCO) who confirmed that Uncle Luther had rented his own room in one of the few buildings that still accepted registered sexual offenders. Corey had talked several times with Uncle Luther and his CCO about staying away from Annie under any and all circumstances. Luther had convincingly promised Corey and his CCO that he would do that. His CCO had vouched for him and agreed to monitor, and, because of these things, Corey had worked with all of them so that Annie could live at home. For just an instant, Corey let down her guard, and her face turned haggard.

Annie took a series of quick breaths, then she leaned over in her chair. When Corey touched her shoulder Annie melted back into the chair, her cut hands covering her face.

Corey put a pillow behind her head, then she gently took off Annie’s shirt. She could see purple bruises on her arms, a bone-deep cut across her left elbow. She lifted Annie’s T-shirt. There were welts snaking across her back. A broken rib pushed out the skin under her left arm.

Corey kissed Annie’s brow, undone.

Abe Stein was reading a file as he sat at the big oak table he used as his desk. He was six feet tall and weighed two hundred and twenty-five pounds. His short salt-and-pepper hair was tousled, his closely-cut beard needed a trim, and behind his old table, he looked puzzled. Blackened pipes and his pipe-smoking paraphernalia held down scattered piles of papers. An abandoned Diet Coke can sat beside a stone ashtray. His favorite tweed sport coat was rumpled, and it had a hole in the pocket where a hot ash from his pipe had burned through.

He reread a portion of the file on Theodore “Teaser” White. Abe was a psychiatrist, and he often evaluated prisoners. Still, this file was unsettling. Something had gone wrong for Teaser in prison. He’d become more unstable and, Abe sensed, even more dangerous.

Lou Ballard, a police sergeant built like a pear, sat in the worn leather chair across from Abe, waiting for him to finish.

Abe looked over at Lou. “This guy doesn’t belong on the street.”

“This guy did his time,” Lou replied.

“I know that. But suppose ‘Teaser’ wants another little girl?” Abe was soft-spoken, and he chose his words carefully. He tapped the open file on his desk. “Suppose it’s what he likes?”

“What are you suggesting here?”

Abe studied a spot on the ceiling. “Make him get help. Put him in a program.”

“I can’t do that. He’s already out. And he doesn’t want to be in a program.”

“Talk to him.” Abe leaned forward, focused. “Lean on him. Be yourself.”

Lou snickered. “I’m the one’s supposed to be the hard-ass.”

Try diplomacy, Abe chided himself. He and Lou helped each other often, though they rarely agreed. Making it Lou’s idea sometimes made it easier to find common ground. Abe lit a pipe, tossed the match into a wastebasket beside his desk. “Why’d you send me the file?”

“His CCO red flagged it. I’ve dealt with Teaser, so it came to me. There’s weird shit in there, so I thought of you.” He sat back, smiling meanly.

Abe nodded, oblivious. “The self-mutilation?”

“Right. How about pulling out his own damn toenails?” Lou cracked his knuckles. “He told the doctor he couldn’t feel anything.”

“He was disturbed when he went in. I’d say prison made it worse. Teaser needs help.”

“And be still my bleeding heart.” Lou shook his head. “Doc, he’s in for drug possession with intent to deliver—not some psycho-crime.”

Forget diplomacy. “A plea bargain. Before the girl ran away, Teaser was charged with rape of a child in the second degree. This girl, Holly, she was twelve and she was pregnant.” Abe set his pipe in the stone ashtray. He thought about what to say. “Lou, he was having sex with her for three months. She was eleven when he took her off the street. In prison he says he stopped feeling things. According to the file, Teaser’s unusually bright. What do you think he’s capable of now?”

Lou pointed at the smoke rising from the fire in Abe’s wastebasket. Abe stood, frustrated and surprised, as always, by his own absent-mindedness.

Lou laughed out loud, a gravelly sound.

The phone rang. “Abe Stein,” he said, pouring the remains of the Diet Coke onto the fire set by his tossed match. “Oh no…” Lou shook his head, watching the smoke. Abe whispered something then hurriedly cradled the phone. “Gotta go,” he muttered and tapped Lou on the shoulder on his way out the door.

Fifteen minutes later Abe ran up the wide stairs of the old hardware building just south of Pioneer Square. The paramedics were packing up when he burst from the elevator, running toward Corey’s office. Annie was on a gurney being wheeled out the door. Abe took her hand, squeezing gently. Annie smiled at him, a thin, sad smile. The lines in his face deepened as he watched her being wheeled out.

When the last paramedic had left, Corey put her arms around him. “It’s my fault.”

“Our fault.”

“You said it could happen.”

“Could, not would. A possibility.”

“He found her on the Ave, brought her to an abandoned building in the trunk of his car. She jumped through a locked window to get away.”

He held Corey close. He knew how troubled she’d been about bringing Annie home. How she’d labored over that decision. He’d encouraged Corey to meet with Luther and his CCO to work it out. He stepped back, trying to get his bearings. The price for their mistake was too high.

“The police are there now,” she said quietly. “Mom is saying Annie fell. She swears Luther didn’t do it, that he was out with her.”

“Let’s make sure Annie’s safe, then we’ll deal with them.”

“Abe, I blew this. It’s—”

He touched a big hand to the small of her back. “She’s still alive, babe. Let’s do what we can for her.”

Billy’s eleventh-grade family night was at 5:30 on Queen Anne Hill. Abe and Corey agreed to meet there at 6:00, after his last appointment. She’d pick up Billy as planned.

Corey cancelled a meeting and went to check on Annie at the hospital. She stayed at Harborview until Annie was sleeping soundly, safe and settled, then Corey called her lawyer, Jason Weiss.

She told him about Luther and Annie. When she asked him to get a court order to keep Luther away from the battered girl, he said, “It doesn’t often work.”

“I’m going to talk with him,” she replied. “I need a starting place.”

She could picture him, thinking about it, rubbing his right ear lobe between thumb and forefinger. “That could work,” he admitted.

Some time later, she didn’t know how long, Corey made her potluck purchase, then she went home to pick up her son.

Billy was brooding. When she pulled up, he was sitting on the front porch bench looking up at the clouds. On the way to the truck he just stared at his phone scrolling through old text messages, shrugging noncommittally when she asked how he was doing. Now he was leaning against the window of their black pick-up, staring at the faces on Broadway. They lived on Capitol Hill, and Corey was coming south on Tenth, anticipating the soft right past the Harvard Exit Theater, toward Lake Union. At the last moment she veered left, following Billy’s eyes down the busy street.

Broadway wasn’t picturesque, like the waterfront, or old, like Pioneer Square. It was, however, Broadway, and it was, in its way, a Seattle phenomenon: quirky street life, hip stores, the “hot” spots, the fringe. Corey drove slowly, trying to see it through his eyes. Wild hair colors. Pierced body parts. Cross dressing. Ethnic restaurants. Gay bars. Straight bars. Edgy clothing stores wedged between fast food franchises. Tourists. Tattoo parlors. Homeless people. A fancy market (the QFC). Sex shops. Smoke shops. A trendy mall. Dick’s Drive-in. College kids. Street kids spanging, asking for spare change. Suburban kids. City kids. Cruising. Drugs scored at ice cream parlors, pizzerias, hamburger stands.

Much of her work led to this odd adolescent mecca. She found runaways and this was one of the places they ran to. And though she knew the kids, knew every shop and every stoop, Broadway was still as foreign to her as the mountains on the moon. Growing up, she worked summers on a fishing boat, and after school at the wharf, canning fish. As a teenager Corey didn’t have free time. Billy smiled, a girl with blue and green streaks in her hair was blowing bubbles. “You’re awfully quiet,” she said. “Something wrong?”

“Mom.” It came out ma-umm.

“Okay. Sorry.”

At the light, a woman in rags pushed a shopping cart full of garbage in front of their car and into the QFC parking lot.

“I can’t reach Aaron.”

“What do you mean?”

“He’s not responding when I text. I call, I go straight to voicemail, which is full. He’s not at school. Two days now… Today I couldn’t find Maisie.”

“Won’t Aaron be there tonight?”

“Un-unh, I don’t think so.”

“And that’s okay? It’s his house.”

Billy shrugged. “His dad stays out of stuff, unless Aaron says fireman instead of firefighter.”

“Easy—”

“Sorry. He’s just so serious…his mom’s in New York.”

She turned down Denny, thoughtful. “His dad’s pretty high up at Olympic—”

“Yeah, a dean.”

“Just what does he do?”

“Tries to figure out what’s going on, I guess.” Billy tapped his thumb on the seat. “If there’s a problem, he decides what’s okay. Like where you can use your phone. Or if something’s racist.”

“I see…I could ask him about Aaron tonight.”

“That’d be okay. Don’t talk about me.”

“Hmm-hmm.” It was quiet until Corey asked, “Storm game tomorrow night?”

“Cool.”

At Seattle Center they turned up the hill to Aaron Paulsen’s family’s home. The Paulsen’s house was a series of glass and metal planes, cleverly assembled to form cleanly-articulated, overhanging rooms with sweeping views. From the front door Corey looked south, toward downtown. Cream-colored clouds and flat skyscrapers were etched in a hard, blue sky. A sunset played streaky pink off the vast reaches of glass. The islands to the southwest were fir-green mounds floating in the dark waters of the Sound. The snow-capped Cascades circled behind the city to rest against Mount Rainier, glistening pink in the sunset. Corey turned away from the view. Backlit by the cream and pink striated northern sky, the Paulsen’s dream house was a little chilly.

“What’d you bring?” Billy asked.

“Sweet and sour pork.” She raised her eyebrows, a question. “From Chungee’s.”

He put his arm around her. “It’s okay, mom.” At the door, she leaned against her boy. They had the same lithe, athletic bodies, though he was half a head taller; the same black hair, though hers was cut short, and his was tied back in a pony tail. She wore form-fitting jeans and a sweater. His jeans were older. He had a tear in his left back pocket and a hole at his right knee. Billy’s T-shirt was from a rock concert at the Gorge. Some group she didn’t know.

She glanced up at her teenage son fidgeting on the doorstep, his arm draped around her. Along with Abe, he was the person she liked best in the world. Billy’s arm dropped to his side as the door opened.

Inside, modern art mixed it up with French Provincial furniture. The potluck offerings were spread across a vast pine table. She saw lots of pasta and vegetable casseroles. Corey finally set her Chinese take out alongside a fancy platter of spinach lasagna.

Billy found a friend and disappeared into the basement. Corey looked around for someone she knew. After more than a year with these people, she still felt like she had to work to keep from making a mistake. Near the window one of the soccer moms, Susan Hodges, a single mother who had a big job at Amazon, was talking with Aaron’s dad, Toby Paulsen, the dean at Olympic and their host at the potluck. Another mom she didn’t know was listening in.

“Hey, Corey,” Toby called as she came over.

He wore a brown corduroy sport coat and old grey Dockers. Shoulder length brown hair framed a thin face. Toby was serious, the descendant of Danish school teachers. The one time she’d seen him angry, Corey remembered him as stern, rather than fierce—more kindly reverend than Viking. Toby shook her hand. “Nice,” he said, noticing the tattoo on her wrist.

“This?” She raised her wrist, showing off a bracelet braided with red, turquoise and black strands. “I was seventeen.”

“Ahead of your time.”

Hardly. “I didn’t mean to interrupt,” Corey said, wanting to talk about other things.

“You’re not,” Toby assured her, then looking at the two women he had been talking with, “I’d like to hear how Corey feels about this.”

“About what?”

“We’re considering a presentation on bisexuality.” Toby adjusted his bifocals, attentive. “Maybe a bisexual support group.”

“A what?”

“A group at school to read and discuss issues. Bisexuality is a viable option for the young people in this community,” he explained.

It is? She hesitated. “You sure you want my opinion?”

Susan nodded.

“Of course,” Toby added.

“I was in prison. In that community, there was a bisexual action group. I put a fork through a woman’s cheek to stay out of it.”

“Uh…I’m sorry,” Susan said. “I didn’t know.”

“It’s okay. Listen. These kids have enough trouble with regular, old-fashioned—”

“Regular?” Toby frowned.

“Uh…gimme a break here, Toby.”

The other mom excused herself and went to the buffet.

Toby hesitated, made a steeple with his fingers. “Corey, how well do you understand homophobia?”

“C’mon, I don’t care who these kids have sex with—so long as they come to it fairly—”

“Fairly, yes—”

“Because they want to, not because they think it’s a viable option.”

“Isn’t that Abe?” Susan interrupted, pointing out the window.

Corey’s husband was getting out of a burgundy-colored ’99 Oldsmobile with freshly-painted white trim. Abe was looking at the sky, scratching his salt-and-pepper beard, trying to figure something. The car was driven by an elderly Chinese.

“Who’s driving?” Toby asked.

“Abe doesn’t drive,” she explained. “That’s Sam, his driver.”

“Why doesn’t he drive?”

“He sideswipes parked cars. Abe’s often pre-occupied.” As if to make her point, Sam took Abe’s arm, steering him around a puddle.

“I see,” Toby said.

She changed the subject. “Where’s Aaron?”

“He’s staying with his grandmother while his mom’s in New York.”

“Billy’s been trying to find him.”

Toby wrote the number on a napkin.

“Thanks.” Corey took the napkin, then saw Abe. “’Scuse-me.”

Abe was near the metal front door. She waved, caught his eye. He was getting an earful from several parents. His half smile—Abe was drifting—made her feel better. Corey saw him take out his pipe, a sure-fire crowd disperser. She hurried over.

Abe’s bearing changed. He put his pipe in his jacket pocket, straightened up, then wrapped his arm around his wife’s slender waist.

Corey leaned against him, relaxing a little.

Stay cool in your mind, Teaser was thinking. He was working the grill at the Mex drive-thru. Sweating. His eyes were watering and burning from the smoke. He had to keep this job. It was part of the plan. So he had to pay attention to his boss, Raoul, who thought cooking freeze-dried greaser food for minimum wage was some kind of an honor.

While he grilled chicken and vegetables for the fajitas, he was getting ready. Going over the list in his head. Taking his time about it. He had four things left to do today. And everything had to be perfect—just so. He thought about Maisie. He could picture her now. He’d watched her from the shadows. Invisible. He’d learned to be careful. Finally. And he’d learned that if you were careful, if you took your time, your time would come.

Just like that, Raoul was there with a spatula, turning the soft, shriveled-up green peppers right in front of him, yelling in his ear about how he had to pay attention, take pride in his work. Teaser could feel the heat, inside. The drive-thru cook telling him to be careful? His thin lower lip slid between his teeth as he numbed up. Teaser looked at Raoul, said “Sorry, sir,” then nodded at everything.

On his break he stepped outside. Under a tree Teaser stuck the point of a plastic toothpick under his thumbnail. He watched it disappear under his skin. Later he pressed on his nail, wondering how to let the bad blood out. When he raised his thumb it caught the moonlight, and he thought he saw a little blue line.

The Logan-Steins lived on 14th Avenue East, near Roy. After serious negotiating—Corey wanted Ballard, a port-oriented neighborhood; Abe favored downtown, or anywhere close—they compromised on Capitol Hill. It was an older residential area ten minutes from downtown. Capitol Hill had a mix of grand old homes, wood-framed houses, stucco, brick—apartments, condos, commercial—a little bit of everything. It was also a comfortable mix of families, seniors, students, and singles and couples of every sexual orientation. Fifteenth Avenue East, with its busy stretch of neighborhood shops, markets, and restaurants, parted the hill at its highest point. Five blocks below, Broadway was an artery, pumping life through the Hill. Pike Street, a trendy, though still-funky, commercial and nightlife center, ran down the south slope. Part of Capitol Hill’s charm was the tree-lined residential streets so close to the shops, the cafes, the fringe theaters, the lakes and the leather bars. Volunteer Park, with its cruising gay men and pick-up frisbee games, fronted some of the oldest mansions in Seattle.

Their street was quiet, mostly three and four-bedroom Victorians, with a sprinkling of condos. At their corner the rundown stone mansion was often for sale. They piled out of the pick-up at 9:00 p.m.

“You got homework?” Abe asked Billy.

“Not much.”

And then they were home. The Logan-Steins’ traditional, wood-framed house had been built in 1927. The day they bought it, Corey insisted that it be repainted. She chose grey, then forest green trim. Inside, the walnut woodwork was kept as perfectly as the trim on her 1930s hardtop wooden yacht, the Jenny Ann II.

“Sit,” Corey said to Billy. She lit a fire in their fireplace, then sat on the stone hearth facing him. “What’s a bisexual support group?”

Billy frowned. “Mom, you didn’t start in on that, did you? It’s like Toby’s new big thing.”

“Why?” Corey asked, confounded.

“Why what?”

She took a measured breath. “Nevermind. You still like Olympic?”

“It’s okay.” Billy shrugged. “You picked it.”

“When I got out of jail, you were failing two courses in public school. Most days, you weren’t showing up. We needed to do something. We couldn’t get you into Northwest, or University Prep. Olympic was new. They meant well…” Corey let it go; she was rationalizing.

“And now he’s getting good grades and showing up,” Abe pointed out.

“I’m not bisexual, mom. I don’t have a boyfriend or a girlfriend. And I still miss Morgan. Okay?”

Corey held back a smile. “Okay…have you heard from her?”

“Just an email, maybe two weeks ago. She loves New York City. She’s not coming back for Christmas. She didn’t ask me to come out there either. I’m sure she’s got a new boyfriend.”

“Did you respond to her email?”

“Not yet.”

Corey bit her tongue, pretty sure that Morgan was still Billy’s girl. A mom’s intuition, she was well aware, but she knew what she knew. And, she knew to stay out of it. Corey changed the subject, “Oh, here’s Aaron’s phone number.” She handed him the napkin. “He’s at his grandmother’s.”

“That’s weird.” He shrugged. “I’ll try again.” Billy loped up the stairs.

Corey watched him, silently offering thanks that family night came just once a year.

“Cor, why are you so down on Olympic?” Abe asked after Billy was in his room upstairs. He was facing the fire, comfortably settled into their worn couch.

Corey came over, unsure how to answer. She sank into the couch beside him. Just thinking about this made her tense. Eventually she turned. “I’m worried, I guess, that something’s not working at that school.”

“What are you thinking?”

She wasn’t sure. “Okay. At Olympic they have like their own very demanding little world: character contracts, a social justice club, anything and everything to get into an Ivy League college. And in this world, everything is supposed to be a certain way. Fine. I could live with that,” she hesitated, “except they don’t get it about kids.” She took another moment. “I mean teenagers are supposed to bounce around. They’re confused… You and I expect that.” She watched him nod; sure, of course. “At Olympic, the adults expect the kids to be, I dunno, fully formed…” Corey just stopped, unable to fathom this. “Since when are kids supposed to know what to believe, what to eat, even—for Godsake—how to feel?” And leaning in, “When I was growing up, I didn’t know anything.” She made a rueful face; it was true. “What I did, I learned to start with what’s real. Including the bad stuff. They start with what they think something should be. It’s the opposite of what I do. I think that’s the problem—I’m not like them. And I don’t want my son to be like them either.”

“People who send their children to private schools aren’t all the same—”

“Okay, maybe it’s me. I’m different. I mean I think it’s fine if Billy goes to a community college. I don’t really know what a start up is. And I like hot dogs. These people make me feel like I should apologize for those things.” Corey sat back, frowning.

“Cor—” Abe brought her back.

“Sorry. Bear with me. I’m starting to get this. What I think is that at Olympic, they hand down all these ideas about how to be, they tell these kids what they should feel, then they leave them to work it out on their own. I mean they made Billy sign a contract about being a good person, told him ‘bisexuality was an option,’ but no one notices when he’s lonely or low. It scares me. There’s no safety net. No regular, reliable, grounded conversation. The grown-ups come on so righteous, so certain of where these kids need to go, what they need to be, and then they don’t even see it when a kid feels bad.”

Abe was looking at the fire. “What’s worse,” he turned, “I’m afraid the kids know that.”

“Yeah, they do. He’s my son, Abe. No one in my family has ever gone to college. His grandmother raised me on a fishing boat…”

“How old were you when she died?”

“Seventeen. Same as Billy. And don’t start that psycho mumbo jumbo with me.”

“Right.”

“Toby asked Billy to volunteer at a shelter in a church on Broadway. He said it would look good on his college applications. When he was locked out of foster care, Billy used to sleep at that shelter. When I explained that to Toby he said, ‘Not to worry. The take away from Billy’s time in foster care and Juvie is that it will help his story for an Ivy.’ His words—no kidding.” She took Abe’s hand. “Billy won’t tell his friends we go duck hunting. And he eats tofu burgers. I didn’t know what tofu was until he started at that school.”

“Your son is just like you.”

“You think so?”

“Forget what he eats. Watch how he thinks, how he handles hard things—in every important way, he’s his mother’s son.”

“Huh,” was all she said. Corey leaned against him, pensive, wondering if this could be true. She loved the idea, but she couldn’t stay with it. She closed her eyes. What was bothering her? Something more about Olympic. It took a moment to get at it. She was worried, she realized, that these people would make Billy feel ashamed, yeah, like the things she’d taught him were old-fashioned, or even silly. And then, without meaning to, they’d come between her and her son, break the connection they’d built so carefully, when things were at their worst.

From the day he was born, she knew what Billy was feeling. But before Billy turned thirteen, his dad disappeared, and drugs were planted on her boat. At her trial a man warned her that Billy could disappear too. In prison she learned violence. It was part of life. Twice she hurt people. It made her feel out of control, stunned by what she could do. When she came out of prison, twenty-two months later, she and Billy had become strangers. Billy said he’d decided that bad things just happened to him.

Here it was, less than two years later, and she, Billy and Abe talked to each other. Checked in. Worked things out.

She glanced up at Abe. Billy was in private school, and Abe thought he was just like her. Her face softened. What a nice thing to say. And it was partly true.

She put her arm across his chest and held him. After a while she whispered, “He’s your son, too.”

Star’s efficiency apartment was in a red brick four story building on Regent, a block and a half east of Broadway. The street had small, run-down, wood houses wedged between newer, cheaply-built apartments and older buildings. A spattering of commercial spilled over from Broadway. From her third floor unit Star could see Alden’s Hair Salon and a used bookstore.

She had one large room with an alcove. Centered on the floor was a king-sized mattress with a baby blue blanket. Beside it there was a Coors lamp and a side table made from two cinder blocks and a piece of plywood. Star kept her bureau against the wall. Her beat-up laptop was on the bureau. In the little kitchen alcove she’d squeezed in a table and two stools. One wide window faced the street.

An empty wine bottle stood on the side table next to a mirror with two lines of cocaine. A half-smoked joint still smoldered in the ashtray, surrounded by cigarette butts. Star, Aaron, and Maisie were on the mattress, naked. Maisie was on her back. Aaron lay beside her, kissing her. Star’s hands were on Maisie’s thighs, spreading her legs. When Star lowered her head, Maisie gently pushed Aaron away. He watched, flushed, as, moments later, Maisie began to tremble. She seemed to relax as her body rocked in orgasm, her second. It was quiet for a moment, then Maisie put a hand behind Star’s neck. She slowly guided Star’s head toward Aaron. Star took him in her mouth. Aaron closed his eyes, leaning back on his hands. After he reached orgasm Aaron fell back onto the mattress beside Maisie.

Maisie leaned in, her short, brown hair pasted by sweat to her forehead. She was intense and sensuous, her adolescent breasts still growing. Maisie ran her tongue along her upper lip, not at all self-conscious, savoring her post-coital feelings. This was new for her and she loved it. Gently, she ran her forefinger along Aaron’s eyebrow then across his cheekbone to the stud in his lower lip. He turned toward her. Aaron was Chinese, adopted at birth. His eyes were brown, steady. His features were sharp, chiseled into his round face. A bright red Z zigzagged through his short, black hair down the left side of his head.

Maisie smiled, sweet and sultry. “We missed family night,” she said.