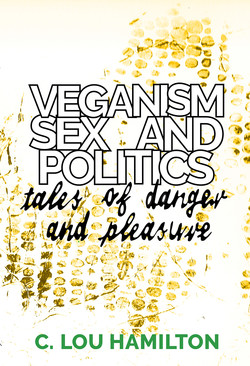

Читать книгу Veganism, Sex and Politics - C. Lou Hamilton - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеINTRODUCTION

Sometime around midsummer 2014, a few months after I started practising veganism, I strolled home from a party in the wee hours, heels in one hand, bag thrown over the opposite shoulder. A hint of sunlight squeezed through the trees. In my head I was still dancing. As I reached the corner near my flat, a fox crossed the empty street and stopped on the pavement some fifty metres before me. She turned my way, looked me in the eyes, and slipped under a bush.

I’d had countless encounters with foxes before this one. London’s vulpine population is thriving, and the animals are second only to squirrels and pigeons for wildlife in my neighbourhood. But this meeting felt different. As I looked at the fox and fancied that she returned my gaze — intentionally, knowingly — I sensed a sudden connection that I intuitively attributed to the fact that I had stopped eating animals.

I am well versed in the concept of anthropomorphism, and in the magic born of dawn dreaming. I have long since abandoned the fantasy that a vegan diet means a human body free from the traces of dead animals, or non-complicity in the exploitation of animals. What I have not lost is that sense of curiosity about other creatures and my kinship with them. While I examine, in the pages that follow, some of the ways that veganism gets tangled up in politics — sexual politics in particular — and what those knots tell us about contemporary identities and other conflicts, I carry with me the memory of this and other trans-species encounters. I open this book with my crossing with the fox because, as I ask a series of sometimes difficult questions about what it means to practise veganism in the early twenty-first century, I want to keep alive this sense of wonder, my ongoing amazement at veganism’s always more-than-political powers.

Why veganism now?

Veganism is hot.

During the second decade of the twenty-first century, veganism in the West has gone from a political practice associated first and foremost with animal rights activism to an increasingly popular approach to eating and living. According to one survey from early 2018, in the United Kingdom 7% of the population now identifies as vegan, a substantial rise since 2016.1 A year later The Economist announced that 2019 would be “the year of the vegan.”2 While surveys and New Year’s predictions need to be taken with a grain of salt, it is clear that more and more people are implementing or considering a plant-based diet.

Veganism’s rising popularity can be attributed to a range of factors. In the first place, it is evidence of the success of animal rights and welfare activists in documenting, publicising and challenging the exploitation of animals raised for food, especially on modern industrial farms, since the second half of the twentieth century. In Western countries such as Britain and the United States, agriculture underwent a transition to greater intensification after World War Two. Technological developments, pesticides, new breeding techniques and the use of vitamins and antibiotics facilitated the rapid expansion of intensive animal agriculture.3 By the 1960s and 1970s, animal advocates were increasingly concerned about the conditions on what were soon dubbed “factory farms.” Ruth Harrison’s 1964 book Animal Machines and, a decade later, Peter Singer’s Animal Liberation: A New Ethics for Our Treatment of Animals, were instrumental in raising awareness of welfare issues related to industrial farming in Britain and the U.S.4 During the same period, scientific research increasingly demonstrated that the animals raised for food or used in scientific experimentation are intelligent and sentient beings who experience and express emotions and feel physical pain.5

By the early twenty-first century there is also increasing evidence that animal agriculture is dangerous for people’s health and for the very future of the planet. The survey cited above names the growing concern about climate change as the most significant factor in veganism’s newfound popularity.6 Parallel to this we have seen a growth in movements for clean eating and living that often promote plant-based diets. In the digital age, information about the negative impacts of animal agriculture and the consumption of animal products, along with alternatives, circulate readily and rapidly to large audiences, increasing access to information about veganism.7 According to the presenter of a BBC radio programme on vegan diets broadcast in February 2019, “When I ask people why they would like to give it [veganism] a try they usually say that something they saw on the television or on social media has changed the way they’ll think about meat and dairy forever.”8 Some people celebrate the growing enthusiasm for veganism as proof of increased compassion for animals and greater awareness about the dangers of climate change, especially among younger people. But not everyone is happy about veganism going mainstream. Some fear that it is losing its political edge, becoming just another middle-class lifestyle choice, complete with celebrity backers. Evidence that a preoccupation with healthy eating and the environment is behind veganism’s popularity prompts some to fear a loss of focus on animal rights.9

There is certainly room for criticism of vegan consumerism. But in this book I argue that it is a mistake to assume that veganism is nothing more than a lifestyle choice. I am also wary of accusing some vegans of having self-centred rather than properly political motives, or of being driven by the wrong kinds of politics.10 It is not possible, or desirable, to think of the lives of other animals, human health, economic inequalities and environmentalism as separate issues. If discussions about climate change teach us anything, it is just how deadly the ideology of limitless economic growth, and the day-to-day activities of many of us living in the West, have become — for ourselves, the rest of the world’s human population, other creatures, and the planet as a whole. The deadliness of many aspects of Western culture and consumerism is hardly news. But it is given new dimensions by the current planetary crisis. The turn towards veganism is one expression of a growing consciousness about the enormous costs of global capitalism and anthropocentrism — the worldview that promotes human beings and our interests as the centre of the universe.

As it becomes more popular, veganism has become a hot topic. We can find a plethora of vegan cookbooks, blogs and online cooking classes, veganism is in the news on a regular basis, and there is even an emerging academic subfield of vegan studies.11 Activists, journalists and scholars debate the pros and cons of veganism for human health, animal welfare, food security (the ability to feed the world’s growing human population), food justice (equal and fair access to healthy food for people) and the earth’s future. So veganism is also hot as in “hot potato.” It attracts attention because it reflects changing attitudes towards animals, food and the environment; but it also creates anxiety in relation to other social, economic and political issues, including class, race, gender, sexuality, disability, gentrification, globalisation and environmental protection. Why does veganism raise hackles? In this book I explore some ways we might think critically about veganism so that we can appreciate its values and better understand the controversies it causes, without equating it to those. Amidst the sometimes stifling debates, I want to give veganism some space to breathe.

I define veganism as an ethical commitment to live, as far as possible, without commodifying or otherwise instrumentalising other animals for our own human ends. Adapting Deane Curtin’s theory of “contextual moral vegetarianism,” I advocate the practice of contextual ethical veganism. Although I believe it is impossible to draw a sharp distinction between the care of other animals and care of one’s self and other people, I follow common usage among vegans by using “ethical veganism” to signal a commitment motivated by compassion for other creatures and not primarily a concern about human health. While “ethical” and “moral” are used largely interchangeably in everyday speech, I choose “ethical” in order to avoid the easy slide of “moral” into “moralism,” a term sometimes (incorrectly in my view) associated with veganism. Following Curtin, I include the word “contextual” in my definition in order to signal a recognition that veganism defined in strict dietary terms may not be appropriate to all situations, given significant differences among people, our histories and our circumstances.12 Those who are able to practise strict veganism need not — indeed, should not — adopt a universalist position by arguing that everyone, regardless of material and cultural context, must practise veganism in a particular way. Finally, following common usage in writing on animal rights and welfare, I refer collectively to nonhuman species as animals, while remaining aware that people too are animals. I try to avoid lumping all other-than-human animals together by being specific, wherever possible, about which species I am referring to.

In practical terms, in contemporary Western societies, practising contextual ethical veganism means avoiding as far as possible the consumption of products made from animals instrumentalised for human ends, and seeking to minimise other practices involving the exploitation of other species. Whereas in popular parlance veganism is normally associated with diet, this book goes beyond food to consider some of the other ways people consume or instrumentalise animals, including for clothing, medicine, pleasure and work. While the book offers a defence of veganism, it draws attention to what I consider unsatisfactory or even dangerous arguments in its favour. It also examines the merits of some arguments against veganism and takes into account some of the challenges of practising veganism today.

The book’s objective is twofold: to invite readers from different backgrounds to take veganism seriously as an ethical practice with important political implications, and to encourage readers to think in ways they may not have before about the relationship between veganism, sexual politics and other political issues, including anti-racism, environmentalism, anti-capitalism and anti-colonialism. My words are neither the first nor the last; I draw on existing discussions, try to take them in different directions, and hope to keep the conversations moving.

Veganism, sex and politics

Sex is also a hot topic, but in a more obvious way than veganism. Why sex, politics and veganism? If you picked up this book hoping for tips on how to find your ideal vegan lover, or help to boost your sex life through a plant-based diet, you’re likely to be disappointed.13 I’ll leave the hottest vegan competition to others.14 Instead, I set out to examine some of the ways veganism crosses paths with sex and other political topics. Sex, sexuality and sexual politics provide examples of how ideas about veganism and people’s relationships with other animals get caught up in complex questions about intra-human relations.

I use “sexual politics” in a broad sense, incorporating sexuality, sexual orientation and sexual relations, as well as power dynamics among different groups of gendered human beings (women, men, transgender and non-binary people). To many readers, sexuality and veganism may not seem immediately related. Yet both share the widespread and persistent perception, on the left as well as the right, that they are luxury issues, not serious political questions. This book begs to differ. Perhaps the most obvious connection between sexuality and veganism is that both are linked to bodies, our own and those of others. These days it is something of a cliché to say that “food is the new sex”; food and sexuality have become intimately tied through the themes of desire and identity.15 But when we expand the scope of veganism beyond food we relate to bodies in different ways: through the medicines we take, the clothes we wear, the intimate relationships we form with human and other creatures, and the ways we travel and move in the world. Thinking about veganism in relation to sexual politics has helped me better to understand the extent to which eating, dressing, playing and taking care of our bodies and those of other people depend and impact upon the bodies and lives of other animals.

The book also examines how different power relations among people — including, but not exclusively, gender relations — intersect with definitions of animality and humanity. In the early twenty-first century most people who study the history of human-animal relations agree that there are ideological and historical connections between the ways in which animals, women and other oppressed human groups — people of colour, Indigenous people, Jews, queers, workers, disabled people — have been represented and treated as less-than-human by people with power. There is also a recognition that the construction and treatment of certain people and collectives of people “as animals” is structurally connected to the (mal)treatment of other animals. Where there is less agreement is how exactly these connections work, and where and when it is appropriate to make comparisons between different forms of intra-human and human-animal relations.

I look at some of the controversies surrounding these comparisons in chapter 1. There I explain how my approach to the sexual politics of veganism differs from the theory of “the sexual politics of meat,” a term coined by the American ecofeminist Carol J. Adams in 1990. Adams’s understanding of the relationship between vegetarianism/veganism and feminism continues to hold considerable sway in Western writings on veganism.16 While “the sexual politics of meat” model of feminist veganism is useful for understanding how cultures of misogyny and meat-eating are entwined in the contemporary United States and other parts of the West, I find its understanding of gender relations and its reliance on anti-pornography feminism reductive and restrictive. The approaches I adopt in this book are critically queer and feminist. I have been influenced by older arguments about animal rights and more recent writings on veganism, especially by queer activists and feminists of colour.17 Recognising that violence — against women, gay men, transgender, non-binary people, among others — is an important element of power relations, the queer feminism I embrace does not take sexual and other forms of violence to be the main basis for feminist action. My subtitle — “Tales of Danger and Pleasure” — is a nod to a landmark feminist volume on sexual politics, Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality, which challenged anti-pornography feminism’s interpretation of sex as dangerous for women.18 By adopting and adapting this title, I signal that although veganism is a site of potential danger — especially when it is misunderstood as being in competition with the interests of oppressed groups of people — it is also a source of pleasure.

My queer feminist veganism embraces transpecies kinship and relations, and is open to the powers of veganism to help us challenge and revise our sense of what it means to be human. But I do not claim that veganism is by definition feminist or queer. In his “Queer Vegan Manifesto” Rasmus Simonsen argues that veganism is queer because, in an overwhelmingly omnivore culture, it is deviant and non-normative.19 I am inspired by the utopian thrust of Simonsen’s text, but I am aware that most vegans do not identify as queer and vice versa. My approach to queer feminist veganism seeks to examine the points of encounter and mutual influences among different kinds of relationships rather than emphasise similarities. I broadly follow an intersectional approach that, in Jeff Sebo’s words, “there are respects in which different issues, identities, and oppressions interact so as to make the whole different from the sum of its parts.”20 When veganism comes into contact with other social and political issues it often becomes a flashpoint for debate. These flashpoints provide valuable opportunities for reflection on the multiple and sometimes conflicting meanings of veganism. The book combines an attention to vegan flashpoints — moments of crisis in the present — with an analysis of sticking points, ideas about veganism that recur, time and again, especially when it is seen in relation to other social and political movements, including feminism, queer politics, anti-racism and anti-colonialism. By exploring flashpoints and sticking points alongside a series of personal and other stories about veganism and sexuality, I aim to draw attention to ways of practising veganism that do not pit it against other personal and political priorities.

Veganism in a nutshell

This book is by and large about veganism as it has arisen in the West since the mid-twentieth century, and most of the material it discusses is drawn from Britain and North America. The bias towards English-language Western sources reflects the situation I live and write in. It is also important to grasp the historical context in which contemporary veganism has developed in order to understand the shapes it takes and why it continues to cause controversy. The book is not an examination of plant-based diets and animal ethics per se. Numerous traditions outside Europe have long histories of vegetarian/vegan diets and understandings of human–animal relations that differ substantially from those of Europe. At certain points in these pages I bring in examples from different cultures via stories of vegan activists from those traditions.

The term “vegan” — formed by the first three and the last two letters of the word “vegetarian” — was coined in the United Kingdom in 1944 by founders of the Vegan Society. These people wished to distinguish themselves from those who avoided the flesh of animals but might eat dairy and/or eggs.21 Both veganism and vegetarianism had longer histories. In Britain, the avoidance of meat and other animal products had been promoted, since at least the nineteenth century, by some supporters of campaigns against cruelty to animals as well as feminist, socialist, and alternative health and spiritual movements.22 By the 1960s and 1970s veganism was increasingly practised among activists of the postwar animal rights movement.23 In 1975 arguments in favour of veganism got a significant boost with the publication of Singer’s Animal Liberation.24 A philosopher in the utilitarian tradition, Singer compared the struggle against “speciesism” to civil rights and feminism.25 He argued that there was no rational reason why moral arguments in favour of equality among human beings should not be extended to other animals, so long as those animals could be proven to be sentient and capable of suffering pain. Much of Animal Liberation is dedicated to a detailed account and critique of the exploitation of animals in scientific experimentation and industrial agriculture, and the final chapter of the book is a defense of vegetarianism. Although in subsequent editions of Animal Liberation and other writing Singer shifted his position on where the line between sentient and non-sentient creatures should be drawn, his main argument was clear: the rearing and slaughtering of sentient animals for food and their use in scientific testing causes unnecessary suffering and is therefore unethical.26

Singer’s emphasis on evidence of suffering as the basis for including many animals in the moral community— drawn from the late eighteenth-century utilitarian philosopher Jeremy Bentham— has been controversial. Most notoriously, it has led Singer to argue that some disabled human beings have less value than some sentient animals.27 A number of feminist animal advocates have criticised Singer for providing a rationalist basis for vegetarianism that ignores the emotional dimension of human-animal relations.28 These are serious problems with Singer’s framework. Yet it is difficult to overestimate the impact of Animal Liberation on the development of veganism and the animal rights movement over the past four decades. Published at a time when animal rights activism was on the rise in Britain and the United States, the book is probably the most widely-read argument in favour of vegetarianism/veganism in the contemporary West. For all its association with animal rights, however, Singer is not a rights philosopher and never advocated rights for animals as such. That argument was made by another philosopher, Tom Regan, in his 1983 book The Case for Animal Rights. Regan argued that the rights of animals are violated when they are raised for food and experimented upon and, in consequence, advocated “obligatory vegetarianism.”29 Singer’s and Regan’s books are cited time and again as the main contemporary philosophical defences of animals. They come up regularly in writings about veganism, their arguments sometimes used to represent the views of all vegans. The association of veganism with the work of Singer and Regan has helped to tie veganism to a very particular, and Eurocentric, tradition of rights, rationalism and moralism. This in turn helps to explain why veganism sometimes becomes a flashpoint in debates about animal ethics. Singer and Regan come out of a European humanist tradition that pays insufficient attention to differences among people. Their work has sometimes been used to make univeralist arguments about how all people should live with other animals, arguments that ignore the distinct cultural and economic contexts in which human-animal relations develop in practice.30

While their philosophical defences of animals have been important for the development of vegan ethics, the theories of Singer and Regan have by no means been the only factors. There is a history of vegetarianism and veganism in feminist activism and writing that does not rely on utilitarian or rights philosophy. Just as in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries vegetarianism was associated with a number of alternative political and social movements, in the late twentieth and early twenty first centuries veganism has been practised in some anarchist, feminist and queer movements. The African-American civil rights activist Dick Gregory is sometimes cited as an influence for Black vegans, as is the Rastafarian tradition of Ital.31 Followers of Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism have used predominantly plant-based diets for centuries, as did some of the Indigenous peoples of the Americas before the Spanish Conquest of 1492. Those communities that relied on hunting and fishing did not share a European, Christian worldview that placed human beings above other animals.32 Veganism as widely understood today arose in response to a specifically Western history of human exploitation of other animals. While it is now followed by many people outside this context, veganism should not be used by Western thinkers and activists as a universal moral baseline, to be adopted in a particular way by all people, including those populations colonised by European nations and whose traditions may have involved less exploitative human-animal relations. It is this colonialist conceit that has sometimes made veganism a flashpoint in debates about animal advocacy, racism and imperialism.33

This book acknowledges the importance of the pathbreaking work of Singer and Regan, as well as early animal activists. But it dedicates more space to new generations of vegans who are changing what it means to practise veganism in the contemporary world. The pages here are especially inspired by feminist and queer theories that emphasise veganism as an embodied practice or an expansive expression of care for other-than-human kin.34 It is informed by writers who understand veganism as a contextual and ever-changing practice, an aspiration rather than a moral absolute, an ongoing process of questioning one’s place in the world rather than a secure sense of self. I follow those who understand veganism not as a rationalist calculation of right and wrong, but an expression of the recognition of our dependencies on other animals. The vegan artists, activists and thinkers I cite draw on a range of cultural and intellectual traditions, including, but not exclusive to, animal rights discourse. They recognise that practising veganism does not mean avoiding all forms of death or violence against other animals.35 And they understand veganism as a practice integral to, rather than in competition with, struggles for justice for human beings.

While I welcome wholeheartedly the rise in numbers of people practising veganism, I am wary of turning “vegan” and “veganism” into modern myths, frozen in history and ceasing to be open to change.36 The word “vegan” proliferates on the windows and menus of eating establishments in my East London neighbourhood, and in many of the cities I have visited in Europe, Canada and Mexico. While this trend makes veganism more accessible to some, it also helps to associate veganism with consumerism and healthy, expensive eating. Likewise, the internet is an important resource for vegans and I have used it substantially in this book to access contemporary debates. But I am concerned that the word “veganism” sometimes circulates in social media as a static concept defined exclusively as a plant-based diet. At the same time, I am conscious of the productive use of “vegan” in activist circles in a range of contexts. My own first regular contact with veganism came in turn-of-the millennium queer anarchist circles in London, where vegan food was shared among activists engaged in migrant solidarity, sex worker rights and anti-capitalist campaigns. More recently, on a trip to Mexico in early 2018, I discovered that many animal rights activists use the terms “vegan” and “anti-speciesist” strategically to signal their opposition to animal exploitation in the context of neocolonialism, rather than as a form of consumerism or identity politics. Practising contextual ethical veganism means recognising and being open to these differences, as well as to changing definitions of vegan and veganism.

Beyond moralism and identity

One of the most frequently repeated clichés about vegans is that we are are self-righteous and believe ourselves holier-than-thou. In a world in which moralism plagues so much of political discourse, in which righteousness so easily slides into self-righteousness, it is notable that vegans take the rap for this more than most. As someone who practises veganism I have much more frequently been accused of being moralistic (or of being in cahoots with moralisers) than I have been for supporting any struggle against the oppression of people, even though feminist, queer and anti-capitalist movements are by no means free from obnoxious ranters. In fact, as I show in chapter 6 of this book, vegans can be accused of being moralistic even without opening our mouths. Our very presence is enough to provoke accusations of moralism. This suggests that the gripe is not with vegans ourselves, but with our message. As the philosopher Cora Diamond wrote over four decades ago: “I do not think it an accident that the arguments of vegetarians have a nagging moralistic tone. They are an attempt to show something to be morally wrong, on the assumption that we all agree that it is morally wrong to raise people for meat, and so on.”37 It is perhaps also not an accident that as arguments in favour of veganism become more forceful — in the light of evidence of animals’ abilities to feel and express pain, the abuses of animal agriculture and climate change — enthusiastic meat- eaters find it easier to dismiss the messengers than to engage seriously with the message.

When I say that veganism is not a form of moralism I am resisting not only the bad arguments of some omnivores, but also the bad arguments of some vegans. I am thinking in particular of claims that veganism is a “moral baseline” or “moral imperative” for anyone who cares about the rights of animals. This view is put forth by the vegan legal scholar Gary Francione and the philosopher Gary Steiner, for example, and can be understood as a universalist argument that goes against the principles of the contextual ethical veganism espoused in this book.38 Similarly, I reject claims that veganism is a form of self-sacrifice.39 While veganism does mean giving up certain things, it does not mean giving up a part of ourselves, our most cherished values or interests. Nor should veganism be understood as a form of moral or physical purity. It can only ever be an aspiration, never a perfection. Vegan bodies are not free from the traces of other animals, for many reasons.40 There is no being in the world without killing and death. As Sunaura Taylor puts it: “vegans are not opposed to death. We are opposed to the commodification and unnecessary killing of animals for human pleasure and benefit.”41 Practising veganism means recognising that as human beings we have much to do to minimise violence in the world, even if we can never eliminate it entirely.

By measuring the credentials of individual vegans, arguments in favour of moral baselines or self-sacrifice actually deflect attention away from animals and back onto people. I do not say “I am vegan” in order to emphasise my own impeccable ethics. I usually say “I am vegan” for practical reasons. If I want to coexist with other human beings in an omnivorous society I constantly have to tell them what I do and do not eat and the activities involving animals (dead or alive) I do or do not participate in. I do not conceive of veganism as a statement of who I am — in short, as an identity — though it is sometimes understood in this way. For example, Laura Wright, author of the book The Vegan Studies Project, begins from the premise that “vegan” is a “culturally loaded term” which signals both an identity and a practice. Wright acknowledges that as an identity “vegan” is unstable. There is a “tension,” she writes, “between the dietary practice of veganism and the manifestation, construction, and representation of vegan identity” because “vegan identity is both created by vegans and interpreted and, therefore, reconstituted, by and within contemporary (non-vegan) media.”42 In this sense, we could compare vegan identity to categories such as gender, sexuality, race and class — identities that are constructed through the ongoing, complex interaction between self-identity and wider social forces and discourses.

Without wishing either to dismiss the experience of vegans for whom veganism is experienced as an identity, or to create a hierarchy of different identity categories, I think it is fair to say that vegan differs in important ways from, for example, gender, “race, sexual orientation, national origin, or religion.”43 For one thing, although the latter categories are all historically contingent, they nevertheless carry a substantial historical weight and collective meaning in a way that vegan does not. Few people are born into vegan families, are assigned vegan at birth or experience discrimination or privilege for being vegan. Some may object that it is just a matter of time before veganism becomes something inherited, complete with a recognised community history and collective memory; and others might claim that vegans can be the targets of discrimination. Yet I suggest that vegan is less an identity than an ethical, and for some political, commitment to end the exploitation of other animals. In that sense, “vegan” has more in common with “feminism” than “woman,” is more akin to “anti-racist” than “Black.” But even here there is an important difference: while one can certainly identify as a feminist without identifying as a woman (to give one example), to “be” vegan is by definition not to belong to the community of beings whose oppression one seeks to end. I would go further: when “vegan” is understood as a category of human identity it actually takes attention away from animals and centres it on people. For that reason identifying “as vegan” carries the risk of anthropocentrism.

The philosopher Chloë Taylor writes of ethical vegetarianism that “it is always constitutive of the vegetarian’s identity. We do not say that we eat vegetarian but that we are vegetarian.”44 Extending this observation to veganism, we could say that it too is “always constitutive of the (vegan)’s identity.” But in order to avoid reductive or static uses of “vegan” and “veganism,” it would perhaps be useful to think of veganism as something we practise or do rather than vegan as something we are. This would allow us, in the words of Dinesh Joseph Wadiwel, “to explore veganism as a set of imperfect practices which are situationally located as forms of resistance to the war on animals, rather than as a mode of identity.”45 Our ethical and political commitments, what we eat and wear, the company we keep — these are all expressions of complex collective and individual identities. They say something about who we are or want to be; in the contemporary world they can form part of what Taylor, following Michel Foucault, calls self-fashioning.46 In this sense, the practice of veganism is entangled in our identities without in itself being an identity. Similarly, we can recognise that practising veganism involves an ongoing process of personal transformation, and impacts on the ways in which we live our lives, even while veganism is much more than a lifestyle. One of the things I want to try to convey in these pages, against a negative representation of veganism either as trendy lifestyle choice or moralistic holier-than-thouism, is the joy of striving to live as people, caring for ourselves and others, without depending upon the endless exploitation of other animals.

Vegan stories

Stories are a great way to educate, share information, pass on pearls of wisdom in ways that can adapt to each individual that hears them, and our ability to reflect on our own stories, integrate the learnings and then reframe them and share them with our insights are powerful acts of magic.47

I am not the first to tell my vegan story. Over the past several years more and more people are writing or talking about veganism, including its relationship to gender, sexuality, race, class and disability. Their tales appear in blogs, online magazines and social media; newspapers and television; documentary and fiction film; PhD theses, academic books and journals; and at conferences where academics and activists converge.48 There is also a popular tradition to be found in zines and pamphlets, and in the recorded oral histories of animal rights activists, as well as autobiographical writing by vegans. This book draws on a number of these sources, interweaving them with my own autobiographical experience and reflection.

The stories I tell look at veganism from different angles: how and why people come to practise veganism; how we face different difficulties, including practical challenges and those of combining veganism with other priorities in our lives; how veganism relates to our different identities, including sexuality and gender; people’s encounters with other animals — dead, alive and imaginary — and how these shape our ideas about veganism; and some of the pleasures of practising veganism. The topics I cover include: comparisons between violence against animals and violence against women and other human groups (chapter 1); feminist arguments for and against veganism (chapters 1, 2 and 4); the relationship between veganism and environmentalism, including climate change activism (chapter 3); how some people have confronted the ethical dilemmas of practising veganism in the face of serious illnesses, and other issues related to caring for ourselves, other people and other animals (chapters 4 and 5); real and fake fur and leather, especially their use and meanings in some queer subcultures (chapter 5); anti-colonial and anti-racist arguments for and against veganism (chapters 5 and 6); the mainstreaming of veganism and the rise of vegan consumerism (chapter 6); and fictional representations of vegans and vegan futures (interludes 1 and 2). This list is not exhaustive. New research, writing and artistic work on veganism — and, in the academic context, critical animal studies — are appearing on a daily basis, and I apologise in advance for missing any important new evidence or arguments. Many themes are not covered in detail in the book: religious arguments for and against veganism; the dilemmas of vegans sharing our lives with carnivorous companion animals; veganism and debates about women’s eating and body image. Where I have not trod this time other writers have, and more will surely follow.49

At points in the subsequent pages the reader may say, “What on earth does this have to do with a plant-based diet?” The sections on sex work, naturopathic cancer treatments and queer leather communities (in chapters 1, 4 and 5 respectively) might make a few readers squirm. So let me say from the start that mine is a personal, and hence idiosyncratic, take on the sexual politics of veganism. I have followed my experiences, desires and passions as well as the stories and theories of others who have sparked my interest. By retracing my particular path I aim to present aspects of veganism that I believe are underexplored, especially in relation to queer politics and feminism. As veganism becomes more popular and widespread I think it is vitally important to honour its longer associations with radical political movements and alternative communities. And against the common perception that veganism is only for the young and the fit, I want to provide some insight into the peculiarities of coming to veganism in middle age, and about the forces and factors that enable us to change our ways at different stages in our lives. In my own reflections and those of others I have tried to find tales that go against the grain either of stereotypes or mainstream writing. By taking some unexpected turns, I encourage readers to think of veganism from different perspectives, and above all to be open to its powers, possibilities and pleasures, as well as its necessities.