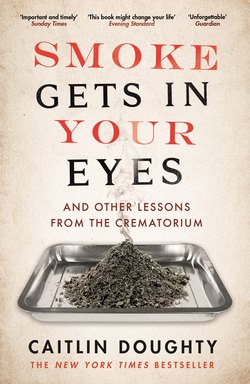

Читать книгу Smoke Gets in Your Eyes - Caitlin Doughty - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPUPPY SURPRISE

My second day at Westwind I met Padma. It wasn’t that Padma was gross. “Gross” is such a simple word, with simple connotations. Padma was more like a creature from a horror film, cast in the lead role of “Resurrected Voodoo Witch.” The mere act of looking at her body lying in the cardboard cremation container caused internal fits of “Oh my God. Holy—what is—what am I doing here? What is this shit? Why?”

Racially, Padma was Sri Lankan and North African. Her dark complexion, in combination with advanced decomposition, had turned her skin pitch-black. Her hair hung in long, matted clumps, splayed out in all directions. Thick, spidery white mould shot out of her nose, covering half her face, stretching over her eyes and yawning mouth. The left side of her chest was caved in, giving the impression that someone had removed her heart in some elaborate ritual.

Padma was in her early thirties when she was felled by a rare genetic disease. Her body was kept for months at the Stanford University Hospital so doctors could run tests to understand the condition that killed her. By the time she arrived at Westwind, her body had taken a turn for the surreal.

Grotesque as Padma appeared in my amateur’s eyes, I couldn’t shrink away from her body like a wobbly fawn. Mike the crematorium manager had made it clear that I was not being paid to be freaked out by dead bodies. I was desperate to prove that I could share his clinical detachment.

Spiderweb face mould, is it? Oh yes, seen it a million times before, surprised this is such a mild case, really, I would say, with the authority of a true death professional.

Until you’ve seen a dead body like Padma’s, death can seem almost glamorous. Imagine a Victorian consumption victim, expiring with a single trickle of blood sliding from the corner of her rosy mouth. When Edgar Allan Poe’s love, Annabel Lee, is taken by the chill of death and entombed, the lovelorn Poe cannot stay away. He goes to “lie down by the side, of my darling—my darling—my life and my bride, in her sepulchre there by the sea, in her tomb by the sounding sea.”

The exquisite, alabaster corpse of Annabel Lee. No mention of the ravages of decomposition that would have made lying down next to her a rancid embrace for the brokenhearted Poe.

It wasn’t just Padma. The day-to-day realities of working at Westwind were more savage than I had anticipated. My days began at eight thirty a.m. when I turned on Westwind’s two “retorts”—industry jargon for cremation machines. I carried a retort-turnin’-on cheat sheet with me for the first month, clumsily cranking the 1970s science-fiction dials to light up the bright-red, blue, and green buttons that set temperatures and ignited burners and controlled airflow. The moments before the retorts roared to life were some of the quietest and most peaceful of the day. No noise, no heat, no pressure, just a girl and a selection of the newly deceased.

Once the retorts came to life, the peace vanished. The room turned into an inner ring of hell, filled with hot, dense air and the rumbling of the devil’s breath. What looked like puffy silver spaceship lining covered the walls of the crematorium, soundproofing the room and preventing the rumble from reaching the ears of grieving families in the nearby chapel or arrangement rooms.

The machine was ready for its first body when the temperature inside the brick chamber of the retort reached 816°C. Every morning Mike stacked several State of California disposition permits on my desk, telling me who was on deck for the day’s cremations. After selecting two permits, I had to locate my victims in the “reefer”—the walk-in body-refrigeration unit where the corpses waited. Through a cold blast of air I greeted the stacks of cardboard body boxes, each labelled with full names and dates of death. The reefer smelled like death on ice, an odour difficult to pinpoint but impossible to forget.

The people in the reefer would probably not have hung out together in the living world. The elderly black man with a myocardial infarction, the middle-aged white mother with ovarian cancer, the young Hispanic man who had been shot just a few blocks from the crematorium. Death had brought them all here for a kind of United Nations summit, a round-table discussion on non-existence.

Walking into the body fridge, I made a modest promise to a higher deity that I’d be a better person if the deceased was not at the bottom of a stack of bodies. This particular morning, the first cremation permit was for a Mr. Martinez. In a perfect world, Mr. Martinez would have been right on top, waiting for me to roll him directly onto my hydraulic gurney. To my great annoyance I found him stacked below Mr. Willard, Mrs. Nagasaki, and Mr. Shelton. That meant stacking and restacking the cardboard boxes like a game of body-fridge Tetris.

When at last Mr. Martinez was manoeuvred onto the gurney, I could proceed with the short trip to the cremation chamber. The last obstacles on the journey were the thick strips of plastic (also popular in car washes and meat freezers) that hung from the doorframe of the reefer, trapping the cold air inside. The strips were my enemy. They entangled everyone who passed through, like spooky branches in the cartoon version of The Legend of Sleepy Hollow. I hated touching them, as I imagined that clinging to the plastic were hordes of bacteria and, it stood to reason, the tormented souls of the departed.

If you got caught in the strips, you would inevitably miscalculate the angle needed to roll the gurney out the door. As I gave Mr. Martinez a push, I heard the familiar thunk as I overshot and slammed the gurney into the metal doorframe.

Mike happened upon me thunking away, pulling Mr. Martinez back and forth and back and forth and back and forth as he walked by, heading to the preparation room. “You need help? You got it?” he asked, one eyebrow arched significantly higher than the other, as if to say, It’s painfully obvious how much you don’t got it.

“Nope, I got it!” I replied cheerfully, brushing the bacteria tentacle from my face and heaving the gurney into the crematorium.

I made sure my response was always “Nope, got it!” Did I need help watering the plants in the front courtyard? “Nope, got it!” Did I need further instructions on how to lather up a man’s hand to slip a wedding ring over his bloated knuckle? “Nope, got it!”

With Mr. Martinez safely out of the reefer, it was time to open the cardboard box. This, I had discovered, was the best part of my job.

I equate opening the boxes with the early ’90s stuffed toy for young girls, Puppy Surprise. The commercial for Puppy Surprise featured a group of five-to-seven-year-old girls crowded around a plush dog. They would shriek with delight as they opened her plushy stomach and discovered just how many stuffed baby puppies lived inside. Could be three, could be four, or even five! This was, of course, the “surprise.”

Such was the case with dead bodies. Every time you opened the box you could find anything from a ninety-five-year-old woman who died peacefully under home hospice care to a thirty-year-old man they found in a dumpster behind a Home Depot after eight days of putrefaction. Each person was a new adventure.

If the body I found in the box was on the unusual side (think: Padma’s face mould), my own curiosity led me to gumshoe-style investigations via the electronic death registration system, coroner’s amendments, and the death certificate. These bureaucratic necessities would contain more information about the person’s life and, more important, their death. The story of how they came to leave the living and join me at the crematorium.

Mr. Martinez was not so out of the ordinary as far as corpses went. Only a three-puppy body, I’d say, if pressed to give him a rating. He was a Latino gentleman in his late sixties who had probably died of a heart condition. Raised up under his skin I could see the outline of a pacemaker.

Legend among crematorium workers holds that the lithium batteries inside pacemakers explode in the cremation chamber if not removed. These tiny bombs have the potential to blow the faces off poor innocent crematorium operators and do damage to the machines. The threat is even greater in the UK, where the operators often do not open the sealed coffins, and just have to go with God and hope they aren’t setting up an unplanned fireworks show. I went back to the preparation room for one of the embalmer’s scalpels to remove it.

I touched the scalpel to Mr. Martinez’s chest and attempted two slices above the pacemaker in a crosshatch pattern. The scalpel looked sharp, but it did nothing to pierce his skin—not even a scratch.

It is not hard to understand why medical schools use cadavers to practise operating techniques, desensitizing their students to the process of causing pain. Performing this mini operation, I felt Mr. Martinez must surely be in agony. Our human identification with the dead always makes us feel like the decedent must be in pain, even though the murk in this man’s eyes told me he had long left the proverbial building.

Mike had showed me how to perform a pacemaker removal the week before, but he had made it look easy. It requires more force with the scalpel than you’d think; human skin is surprisingly tough material. I apologised to Mr. Martinez for my incompetence. After several more unsuccessful scalpel jabs and frustrated noises, the metal of the pacemaker revealed itself beneath the lumpy yellow tissue of his chest. With one quick pull it was free.

Now that Mr. Martinez had been identified, relocated, and stripped of all potentially explosive batteries, he was ready to meet his fiery end. I plugged the conveyor belt into the retort and pushed the button, which starts the assembly-line process of rolling a body into the machine. Once the metal door clunked closed I returned to the science-fiction dials at the front of the machine, adjusted the air flow, and turned on the ignition burners.

There is very little to do while a body is burning. I kept watch on the machine’s changing temperature and opened the metal door a few inches in order to peek inside and monitor the body’s progress. The heavy door creaked when it opened. I imagined it saying, Beware of what you shall discover, my pretty.

Four thousand years ago, the Hindu Vedas described cremation as necessary for a trapped soul to be released from the impure dead body. The soul is freed the moment the skull cracks open, flying up to the world of the ancestors. It is a beautiful thought, but if you are not used to watching a human body burn, the scene can be borderline hellish.

The first time I peeked in on a cremating body felt outrageously transgressive, even though it was required by Westwind’s protocol. No matter how many heavy-metal album covers you’ve seen, how many Hieronymus Bosch prints of the tortures of Hell, or even the scene in Indiana Jones where the Nazi’s face melts off, you cannot be prepared to view a body being cremated. Seeing a flaming human skull is intense beyond your wildest flights of imagination.

When the body goes into the retort, the first thing to burn is its cardboard box, or “alternative container” as it’s called on the funeral bill. The box immediately melts into flames, leaving the body defenceless against the inferno. Then the organic material burns away, and a complete change overtakes the body. Almost 80 per cent of a human body is water, which evaporates with little trouble. The flames then go to work on the soft tissues, charring the whole body a crispy black. Burning these parts, the ones that visually identify you, takes the bulk of the time.

It would be a lie to say I hadn’t had a particular vision of being a crematorium operator. I expected the job would involve placing a body in one of the giant machines and settling down with my feet up to eat strawberries and read a novel as the poor man or woman was cremated. At the end of the day I’d take the train home in thoughtful reverie, having come to some deeper understanding of death.

After a few weeks at Westwind, any dreams I had of berry-eating reveries were replaced by much more basic thoughts, such as: When is lunch? Will I ever be clean? You’re never really clean at the crematorium. A thin layer of dust and soot settles over everything, courtesy of the ashes of dead humans and industrial machinery. It settles in places you think impossible for dust to reach, like the inner lining of your nostrils. By midday I looked like the Little Match Girl, selling wares on a nineteenth-century street corner.

There is not much to enjoy in a layer of inorganic human bone dusted behind one’s ear or gathered underneath a fingernail, but the ash transported me to a world different from the one I knew outside the crematorium.

Enkyō Pat O’Hara was the head of a Zen Buddhist centre in New York City at the time of the September 11 attacks, when the towers of the World Trade Center came down in a scream of chaos and metal. “The smell didn’t go away for several weeks and you had the sense you were breathing people,” she said. “It was the smell of all kinds of things that had totally disintegrated, including people. People and electrical things and stone and glass and everything.”

The description is grisly. But O’Hara advised people not to run from the image, but instead to notice, to acknowledge that “this is what goes on all the time but we don’t see it, and now we can see it and smell it and feel it and experience it.” At Westwind, for what felt like the first time, I was seeing, smelling, feeling, experiencing. This type of encounter was an engagement with reality that was precious, and quickly becoming addictive.

Returning to my first basic concern: When, and where, was lunch? I was given half an hour for lunchtime. I couldn’t eat in the lobby for fear a family would catch me feasting on chow mein. Potential scenario: front door swings open, my head jerks up, wide-eyed, noodles hanging from my lips. The crematorium was also out, lest the dust settle into my takeout container. That left the chapel (if it wasn’t occupied with a body) and Joe’s office.

Though Mike now ran the crematorium, Westwind Cremation & Burial was the house that Joe built. I had never met Joe (né Joaquín), the owner of Westwind: he retired just before I cremated my first body, leaving Mike in charge. He became somewhat of an apocryphal figure. Physically absent, perhaps, but still a spectre in the building. Joe had an invisible pull over Mike, watching him work, making sure he stayed busy. Mike had the same effect on me. We both worried about the iron glare of our supervisors.

Joe’s office sat empty—a windowless room filled with boxes and boxes of old cremation permits, records of each person who’d made their last stop at Westwind. His picture still hung over his desk: a tall man with pockmarked skin, a scarred face, and thick black facial hair. He looked like someone you didn’t want to fuck with.

After pestering Mike for more information about Joe, he produced a faded copy of a local newspaper with Joe’s picture splashed across the cover. In the picture he stands in front of Westwind’s cremation machines with his arms crossed and looks, once again, like someone you didn’t want to fuck with.

“I found this in the filing cabinet,” Mike said. “You’ll like this. The article makes Joe sound like some badass renegade cremationist who took on the bureaucracy and won.”

Mike was right, I did like it.

“People in San Francisco eat that kind of story up.”

A former San Francisco police officer, Joe had founded Westwind twenty years prior to my arrival. His original business plan was to fill the lucrative niche of scattering ashes at sea. He purchased a boat and fixed it up to shuttle families into the San Francisco Bay.

“I think he sailed that thing himself. From, like, China or somewhere. I don’t remember,” Mike said.

Somewhere along the line, the guy storing Joe’s boat made some manner of horrible mistake and sank it.

Mike explained, “So Joe’s standing there on the dock, right? Smoking a cigar and watching his boat sink into the bay. And he’s thinking, well, maybe the silver lining here is that I’ll use this insurance money to buy cremation machines instead.”

Fast-forward a year or so and we find Joe as the owner of a small business, the proprietor of the fledgling Westwind Cremation & Burial. He discovered that the San Francisco College of Mortuary Science had been under contract for many years with the city of San Francisco to dispose of their homeless and indigent dead.

According to Mike, “The mortuary college’s definition of ‘dispose’ was, like, using the bodies as learning tools for their students, unnecessarily embalming all the corpses and charging the city for it.”

In the late 1980s the mortuary college was overbilling the city by as much as $15,000 a year. So Joe, enterprising gentleman that he was, underbid the mortuary college by two dollars a body and won the contract. All the unclaimed, indigent dead now came through Westwind.

This bold move put Joe on the wrong side of the San Francisco Coroner’s Office. The coroner at the time, Dr. Boyd Stephens, was chummy with local funeral homes and, according to the article, not above accepting liquor and chocolate in appreciation for his business. Dr. Stephens was equally friendly with the San Francisco College of Mortuary Science, the place Joe had just beaten for the contract to dispose of the indigent dead. Harassment against Westwind ensued, with city inspectors dropping by multiple times a week finding frivolous violations. For no reason and without warning, the city pulled the contract from Westwind. Joe filed a lawsuit (which he won) against the San Francisco Coroner’s Office. Mike finished with the story with a flourish, announcing that Westwind Cremation & Burial has been open for business, and the San Francisco College of Mortuary Science out of business, ever since.

AFTER LUNCH, AN HOUR or so after sliding Mr. Martinez into the retort, it was time to move him. His corpse had entered the machine feet-first, allowing the main cremation flame to shoot down from the ceiling of the chamber and hit him in the upper chest. The chest, the thickest part of the human body, takes the longest to burn. Now that his chest had had its turn with the flame, his body had to be moved forward in the chamber so that his lower half could do the same. For this I donned my industrial gloves and goggles and fetched my trusty metal pole with a flat solid rake at the end. I raised the door of the retort about eight inches, inserted the pole into the flames and carefully hooked Mr. Martinez by the ribs. The ribs were easy to miss at first, but once you got the hang of it you could usually hook the sturdiest rib on the first try. Once he was successfully hooked, I yanked him towards me in one quick movement. This pull caused a bright burst of new flames as the lower body was at last addressed with fire.

When Mr. Martinez had been reduced to red glowing embers—red is important, as black means “uncooked”—I turned the machine off, waited until the temperature crept down to 260°C, and swept out the chamber. The rake at the end of the metal pole removes the larger chunks of bones, but a good cremationist uses a fine-toothed metal broom for hard-to-reach ashes. If you’re in the right frame of mind, the bone sweeping can reach a rhythmic Zen, much like the Buddhist monks who rake sand gardens. Sweep and glide, sweep and glide.

After sweeping all of Mr. Martinez’s bones into the metal bin, I carried them over to the other side of the crematorium and poured them along a long, flat tray. The tray, similar to the kind used on archaeological digs, was used to search for various metal items that people had embedded in their bodies during their lifetimes. The metal I was looking for could be anything from knee and hip implants to metal dentures.

The metal had to be removed because the final step in the cremation process was placing the bones into the waiting Cremulator. “The Cremulator” sounds like a cartoon villain or the name of a monster truck but is in fact the name of what is essentially a bone blender, roughly the size of a slow cooker.

I swept the bone fragments from the tray into the Cremulator and set the dial to twenty seconds. With a loud whir, the bone fragments were crushed into the uniform powdery puree that the industry calls cremated remains. In California, it is assumed (and is, in fact, the law) that Mr. Martinez’s family would receive fluffy white ashes in their urn, not chunks of bone. Bones would be a harsh reminder that Mr. Martinez’s urn contained not just an abstract concept but an actual former human.

Not every culture prefers to avoid the bones. In the first century AD, the Romans built tall cremation pyres from pine logs. The uncoffined corpse was laid atop the pyre and set ablaze. After the cremation ended, the mourners collected the bones, hand-washed them in milk, and placed them in urns.

Lest you think bone washing hails only from the ancient bacchanalian past, bones also play a role in the death rituals of contemporary Japan. During kotsuage (“the gathering of the bones”) the mourners gather around the cremation machine when the bones are pulled out of the chamber. The bones are laid on a table and the family members come forward with long chopsticks to pick them up and transfer them into the urn. The family first plucks the bones of the feet, working their way up towards the head, so that the deceased person can walk into eternity upright.

At Westwind there was no family: only Mr. Martinez and me. In a famous treatise called “The Pornography of Death,” the anthropologist Geoffrey Gorer wrote, “In many cases, it would appear, cremation is chosen because it is felt to get rid of the dead more completely and finally than does burial.” I was not Mr. Martinez’s family; I did not know him, and yet there I was, the bearer of all ritual and all actions surrounding his death. I was his one-woman kotsuage. In times past and in cultures all over the world, the ritual following a death has been a delicate dance performed by the proper practitioners at the proper time. For me to be in charge of this man’s final moments, with no training other than a few weeks operating a cremation machine, did not seem right.

After whirling Mr. Martinez to ash in the Cremulator, I poured him into a plastic bag and sealed it with a bread-bag twist tie. The plastic bag containing Mr. Martinez went into a brown plastic urn. We sold more expensive urns than this one in the arrangement room out front, gilded and decorated with mother-of-pearl doves on the side, but Mr. Martinez’s family, like most families, chose not to buy one.

I punched his name into the label maker, which hummed and spat out the identity that would be stuck on the front of his eternal holding chamber. In my last act for Mr. Martinez, I placed him on a shelf above the cremation desk, where he joined the line of brown plastic soldiers, dutifully waiting for someone to come to claim them. Satisfied at having done my job and taken a man from corpse to ash, I left the crematorium at five p.m., covered in my fine layer of people dust.