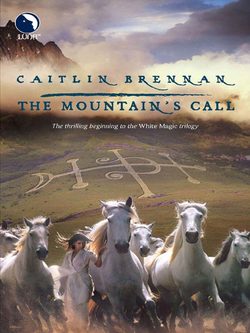

Читать книгу The Mountain's Call - Caitlin Brennan - Страница 17

Chapter Eleven

ОглавлениеThe last test of the Called fell three days before Midsummer. It was the only public test. Those who passed could regard it as an initiation into the life of a rider. Those who failed had the right to vanish into the crowd and be mercifully and formally forgotten.

A great number of people were gathered in the largest of the riding courts, seated in tiers above the floor of raked sand. All the riders were there, and all the candidates who had passed this test in their own day. Students from the School of War, guests and servants filled all the rest of the benches.

Some of the Called had family there. One whole flock of peacocks belonged to Paulus. Valeria saw how pale he was and felt almost sorry for him. She at least did not have to fail in front of a legion of brothers and uncles and cousins.

That gave her an unexpected pang. Her family would never see her here, or know whether she succeeded or failed. Whatever happened, she had left them. She could never go back.

All of the Called waited together in the western entrance to the court. The eights were intact except for Valeria’s, but she suspected that certain decisions had been made. Some of the Called had a drawn and haunted look. Others seemed dulled somehow, as if the magic had drained out of them.

Only a few still had a light in them. Some actually shone brighter. Iliya was one. So was Batu. And, she saw with some incredulity, Paulus.

She could not see herself, to know what the others must see. She felt strong. She had slept last night without dreams, and been awake when the bell rang at dawn. Now at full morning she was ready for whatever was to come.

Supper last night had been water from the fountain and nothing else. There had been no breakfast, but she was not hungry at all. She was dizzy and sated with the air she breathed.

She smiled at Batu who stood next to her. He smiled shakily back. “Luck,” he said.

“Luck,” she replied.

The hum and buzz of the crowd went suddenly quiet. As before, Valeria felt them before she saw them. The stallions were coming.

This time no one rode them. They were saddled and bridled, walking beside their grooms.

Her heart began to beat hard. There was not a sound in that place except the soft thud of hooves on sand, and now and then a stallion’s snort or the jingle of bit or bridle as he shook his head at a fly.

There were eight of them, as always. She had not seen these eight before. They were massive, their coats snow-white. These were old stallions, how old she was almost afraid to imagine. Their eyes were dark and unfathomably wise. The tides of time ran in them. With every step, they trod out the pattern of destiny.

She had an overwhelming desire to fling herself flat at their feet. All that kept her upright was the realization that if she did that, she would not be able to get up again. She stood with the rest of the Called, wobble-kneed but erect, and waited to be told what to do.

Kerrec had appeared while the stallions arranged themselves in a half circle in the center of the court. He called the candidates together in eights, with the broken eight last.

The test was as deceptively simple as all the rest. Each man was to select a horse, mount and ride.

“Ride how?” asked a gangling boy from the second eight.

“That is the test,” Kerrec said.

By now they knew better than to ask him to explain. They exchanged glances. Some rolled their eyes. Others were praying, or maybe incanting spells.

Valeria did not envy the first rider in the slightest. He selected himself, shrugged rather desperately and left his fellows and walked out onto the sand.

The crowd’s silence deepened. The stallions stood unmoving. They did not fidget as ordinary horses would. Their stillness was monumental, rooted in the earth under their feet.

The young man stood in front of them. His head turned from side to side. He was blind, Valeria thought. He could not see what he was supposed to see.

When he moved, his steps were slow. His fists clenched and unclenched. He wavered between two nearly identical white shapes. They looked like brothers, with the same arched nose and little lean ears.

His choice was visibly random. He seized the rein from the groom and flung himself into the saddle.

The stallion did not move a muscle. At first the rider heaved a sigh of relief, but when he asked the stallion to advance, his answer was the same total stillness as before.

A titter ran through the crowd. The rider flushed. His body tensed. Just as he would have dug heels into the broad white sides, the stallion erupted.

The rider went off in the first leap. He landed well, rolling out of reach of the battering hooves. The crowd applauded that, but he did not stay for the accolade. He was gone as he was allowed to do, vanished and forgotten.

The second rider could not choose at all. He turned and fled. The third chose reasonably well, mounted gracefully, and plodded a lifeless circle before he conceded defeat.

Valeria had lost count before any of the would-be riders managed a ride worth noticing. The crowd had been by turns amazed and amused, but even devoted followers of the art were glazing over.

Then a candidate mounted and rode—really rode.

He was a wiry little creature with the pinched face of a starveling child, but he was light and quick on his feet. In the saddle he blossomed. The stallion danced for him, a stately pavane that won a murmur of approval from the benches.

Valeria noticed an important thing. It was the stallion, not the rider, who danced. The rider had the sense to sit perfectly still and not interfere. His expression lingered in Valeria’s memory. He was half terrified and half exalted.

Three more received the gift of the dance, out of three eights. The winnowing was fast and merciless. No one died, but one broke an arm and another left with a bloodied nose.

Then there were the five of them, the broken eight, who were either the best or the worst of them all. The entrance that had been so crowded seemed echoing and empty. The four who had passed the testing so far had drawn to one side, watching with a combination of smugness that their ordeal was done and sympathy for those who had still to undergo it.

People were whispering in the crowd, telling one another why this eight was missing three. Their attention had sharpened.

Paulus went first. He had the most to lose and the least patience to spare. He walked straight toward the tallest of the stallions, but halfway there, he veered aside. When he halted, he was face-to-face with the least lovely of them, a comically long-nosed, long-eared creature with a mottled pink muzzle and a spreading pink stain around one eye.

Paulus’ lip curled. At the same time his hand crept out and came to rest on the heavy crested neck. A small sigh escaped him, as if something inside him had let go. He mounted as punctiliously as always. The stallion shook his mane and pawed once, then gathered himself and rose in an extravagant and breathtakingly beautiful leap.

Valeria felt the lightness, the sheer joy of that dance. It was perfectly startling and perfectly wonderful. Paulus rode it in terror and delight, until he had to laugh or burst into pieces.

The rest of them rode on that lightness. Batu, then Iliya added their own steps to the dance.