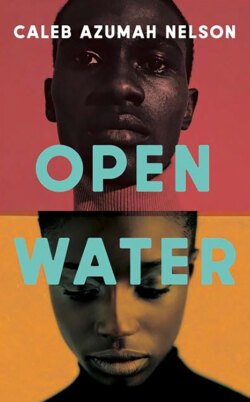

Читать книгу Open Water - Caleb Azumah Nelson - Страница 12

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление5

You say:

The sky has erupted and there’s white ash on the ground. The dog has never seen snow before. It alternates between bounding across the icy planes and staying stock-still, aside from the tiny shake in its hind legs. Your grandma had never seen snow until the year you were born, while she awaited your arrival, and those tender flakes fell in a furious storm, clumping on the ground. She got on her knees and began to pray, for herself, her daughter and unborn grandchild. On the same day, your mother was on the top deck of a bus, cowering as a man waved a gun, and she emerged unscathed. You’re not religious, but when you hear stories like that, it makes a man want to believe. You imagine your grandma in fervour, praying for your body barely formed, your spirit in gestation. Now her body is falling apart, or rather, has already fallen. Her spirit is everywhere. You don’t know if you’ll ever return and see where she has been laid to rest, but on this occasion, you do not have the strength. You’re not religious but you’re praying for your own mother and father as they make the journey back to Ghana, back home. Your knees are on hard wooden floor, prostrating at the foot of your own desires, when the dog nudges you in the back. The dog has never seen snow before. The sheet above is cloudless, lacking in form and detail. Have you ever looked at the sky at night after it has snowed? Orange glow, light caught between somewhere. Makes you want to reach up and touch, so sometimes, you pray. If prayer is mostly desire from the inner self, then you’re praying for a safe trip for her.

She says:

There’s nobody here to hear the soft pad of her feet across gold dust. Warm rush of the ocean. Just needed to get away. Just needed some peace of mind. Just needed to breathe. Sky here is cloudless too. The blue of a heatwave. Summer in January. Funny how time works.

Pulled herself over all sorts of lines to get here. Drew this line from herself to him, her father, all by herself, just to be close. No, the line was there, is always there, will always be there, but she’s trying to reinforce, to strengthen. Blood and bone across the water, across continents and borders. What is a joint? What is a fracture? What is a break? It’s all very difficult. Language fails us, especially when he doesn’t open his mouth. It’s all just, a lot. So she’s reaching into a pocket of time, where there’s nothing but heatwave blue, a summer in January, golden dust stuck between toes, the roar of a quiet body of water.

Also, a thank you. She’s grateful.

You say:

There’s a piece of art which comes to mind by Donald Rodney, titled In the House of My Father. A photo: a dark hand, palm turned upwards, lifelines criss-crossing skin; in the centre of the palm, a tiny house, loosely constructed, held together with several pins. You’ve often had such an image, or something similar, where you are made aware that you carry the house of your father, which means you also carry a part of the house he carried, your father’s father’s, and that this man would’ve done the same. Your first instinct is to ball your hand into a fist, crushing the thing, letting the weight drift to the ground; but perhaps it would be necessary to prise open its doors, to search the rooms which are lit, glance into those which are not, to see what, as of yet, remains unseen. Then leave this place, in peace, with peace, both his and yours, intact.

You know what it means to have to draw the line yourself. You know what it means to have rugged anger melt, when your father laughs so hard at his own joke that tears stream down, down, down. You know what it means to find tears streaming down, down, down. Caught you unawares. A few years ago, and you had to turn off into an alley in the darkness and cry. The rush of memories like the tow of the ocean, the recollection of a man for whom love was not always synonymous with care. You cried like the time he left you in the shop and did not return. You cried yourself hoarse and soft. You cried like an infant does for their father. How ironic. Indeed, what is a joint? What is a fracture? What is a break? Under what conditions does unconditional love become no more? The answer is you will never not cry for your father.

You don’t always like those you love unconditionally. Language fails us, always. Flimsy things, these words. And everything flounders in the face of real gratitude, which even a thank you cannot surmise, but a thank you to her also.

She says:

Language fails us, and sometimes our parents do too. We all fail each other, sometimes small, sometimes big, but look, when we love we trust, and when we fail, we fracture that joint. She doesn’t want it to break and maybe that’s not possible, but she doesn’t want to find out. She’s not religious either, but she knows what she desires.

She’s looking forward to returning home, to a place familiar, where coherence and clarity might make an appearance.