Читать книгу Who Killed Ruby? - Camilla Way, Camilla Way - Страница 8

2

ОглавлениеIt’s almost closing time. Outside on the dark Peckham street rain falls on flickering puddles. A man, weaving in and out of traffic and clutching a can of cider, thumps his fist on idling cars. Beyond him the Rye lies abandoned, its rain-soaked lawns and gardens, ponds and playgrounds cloaked in darkness now.

Vivienne checks her watch: ten to six, only three tables occupied still. Walton, the elderly Trinidadian who calls in most days, finishing his slice of vanilla sponge; a teenage couple on table number four, eyes locked, hands clasped over tea long gone cold. And the doctor. Her gaze flickers over him then away again as it has for the past hour, as it does every time he arrives and takes the same corner table, asking for strong black coffee, pulling a notepad from his jacket pocket and beginning to write. His fingers barely pause as the words flow in a language she doesn’t recognize. She has noticed herself waiting for him each day.

Soon Vivienne begins to shut up shop, pulling the blinds down, collecting menus and sugar bowls. ‘Closing now,’ she calls.

The teenagers leave first, with Walton close behind. ‘Goodbye, Elizabeth Taylor. Goodbye!’ he says. ‘See you tomorrow!’

She smiles and waves him off, turning back to find the doctor standing only a few feet away and she jumps to find him suddenly so close. ‘Sorry,’ she says. ‘Two coffees, was it? Three eighty, please.’

‘Elizabeth Taylor?’ he asks as he hands her the money.

It’s the first non-coffee-related thing he’s said to her. ‘Reckons I look like her, daft sod.’ She laughs to show the absurdity of it, and he smiles politely.

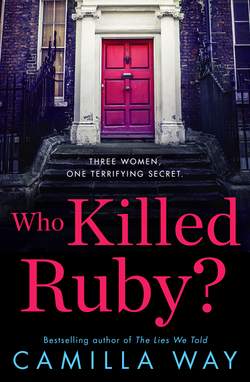

‘This is a nice place.’ He nods towards the pink neon sign in the window that says Ruby’s. ‘And this is your name? Ruby?’ His accent curls around the words. Is he Russian, she wonders. Polish?

‘Oh, no, I’m Viv. Ruby was my sister but she died when we were young.’

He glances at her. ‘I see. I’m sorry for your loss.’

She waves her hand breezily to show how over it she is, though in truth the very thought of Ruby makes her throat thicken, even now. ‘You live near here?’ she asks, to change the subject.

‘I work at the hospital.’ He nods in the direction of King’s College and she affects a look of surprise, as if she hadn’t already clocked weeks ago the NHS tag hanging around his neck, the name Dr Aleksander Petri in black type.

‘Well,’ he pats his pockets as if looking for something and she lets her gaze flicker over him again. He has a kind face, she thinks; his almond-shaped eyes thick-lashed and so dark as to be almost black, his mouth— ‘I must go,’ he says, jolting her from her reverie. ‘Thank you for the coffee,’ and then he is gone, the door thudding gently closed behind him.

Her friend Samar arrives moments later, his hair wet with rain. ‘Was that him?’ he asks, clapping his hands together for warmth. ‘Dr Feelgood?’

‘Yep.’ She fetches the broom to sweep the floor.

‘And?’ He looks at her expectantly. ‘Any progress?’

‘Nope.’ She pronounces the word so that it ends with a satisfying ‘puh’ and Samar rolls his eyes.

‘Ask him out, for God’s sake.’ He follows after her, helping her lift chairs onto tables. ‘Did I tell you Ted’s taking me to Paris?’ he says after a while, with unconvincing nonchalance.

She stares at him. ‘You’ve only just got back from Amsterdam! Jesus, how many romantic mini-breaks does one couple need?’ But she sees the glow in his eyes, sees how the person he was has been transformed by love, and sighs. ‘Ask if he’s got any single straight friends, will you?’

Half an hour later Viv turns the corner into Chiltern Avenue. It’s a wide, tree-lined street, the Victorian semis large and impressive, set amongst spacious, well-kept gardens. She sees her mother’s house ahead and quickens her pace as the rain picks up. Her mum’s corner of Peckham has changed almost beyond recognition in the quarter of a century that she’s lived here, the slow and steady creep of gentrification transforming what was once a shabby, unfashionably edgy part of south-east London into something shiny and desirable, the original demographic squeezed out family by family as loft and kitchen extensions, four-by-fours and a general sheen of exclusivity and wealth has taken its place.

Only her mother’s house stands out from the homogenized, sanitized crowd. Number 72 is a faded kaleidoscope of colours; the paintwork a peeling turquoise, the guttering a weather-beaten red, the door a washed-out yellow. In the front garden rainbow-striped windmill spinners tatty with rain and mud poke up through banks of weeds, and the bent browned husks of long-dead sunflowers bow before a brass sculpture of a naked woman, her breasts and belly green with the passage of time. A trio of wind chimes hang from the branches of a leafless sycamore, their music mingling with the rain.

As usual the front door rests on its latch and Viv pushes it open with a sigh of disapproval but steps into the light, high-ceilinged hall to feel the house’s familiar pull, its peaty, musty smell of boiling pulses; the spicy sweetness of sandalwood and patchouli, and she relaxes into its warmth and familiarity. Her mother runs a sort of boarding house for the waifs and strays of South London: the abused, the addicted, the lost and the lonely. Sent to her by local refuges, psych wards and rehab centres, her guests take up residence in one of the many light and airy bedrooms, some for a few weeks, others for a few months, until they are deemed fit to return home or are found a more permanent place elsewhere. The most cursory of glances reveals this is not a lucrative enterprise, yet somehow the house’s colour, character and atmosphere transcends the worn furniture, the splintering floorboards and grubby paintwork.

To the right of the hall is the kitchen and Vivienne enters it now to find her daughter Cleo seated at the large pine table, her head bowed over her school books, half of which are obscured by an enormous ginger tom lying supine across them, his vast furry belly vibrating with loud contentment. A lightshade made from many pieces of coloured glass throws rainbow squares across the wide, well-worn floorboards. The walls are covered in a jumble of art prints and black-and-white photographs, an Amnesty International poster, a framed Maya Angelou quote. Books crowd together on the shelves; texts on feminism and politics and spiritualism and psychology, and Vivienne doesn’t know if her mother has ever read these books, has never in fact witnessed her read any of them, but supposes that she must have, once.

She goes to her daughter and kisses the top of her head. ‘Where’s Gran? Sorry I’m late, Sammy popped in.’

Cleo looks up at her distractedly, her school tie tugged half out of its knot. ‘That’s all right. Can we go home now? I need to—’

She’s interrupted by the appearance of her grandmother. Stella seems to sail rather than walk into any room she enters. She’s an impressive sight; tall and statuesque, her long grey hair dyed a faded magenta. She wears a voluminous kaftan in shades of green and red with a necklace of brightly painted African beads. She’s in her mid sixties but, rather like her home, the heady mix of colour and flair surpasses the general wear and tear of age and one is aware only of her attractiveness.

Stella’s voice is deep and rich, and seeing her daughter she says, ‘Oh, hello, darling. Now, I came in here for something, but I have absolutely no idea what it is.’ She wanders over to the stove to poke at something simmering there with a spoon. ‘Would you like some nettle and elderflower tea? It’s homemade.’

They are alike, physically, although at five foot six Viv doesn’t quite have her mother’s impressive stature, something she’s both relieved and a little regretful about. ‘Christ, no,’ she says, then takes a seat and asks, ‘who’ve you got staying here at the moment, anyway?’

‘Just four: a new woman came last night, the others I think you’ve met – we still have Shaun, of course.’

She says the name fondly, just as Vivienne inwardly shudders at the mention of Stella’s long-standing guest. Hastily she turns back to her daughter. ‘Did you manage to finish your project, love?’ she asks.

But before Cleo can reply, Stella interjects with a crisp, ‘I doubt it. She’s spent most of her time fiddling with that phone of hers.’

As if on cue, Cleo’s mobile pings and she snatches it up eagerly, while Stella sighs.

Vivienne has noticed a hint of discord recently, like a cold draught blowing between her daughter and mother. It’s nothing she can put her finger on, just an occasional, troubling tension that she’s not entirely sure she’s imagined. She looks at Cleo, tapping furiously on her phone, her school books abandoned. She doesn’t share her and Stella’s pale skin, dark hair and violet-blue eyes, but instead has the same strawberry blond curls, the creamy, freckled complexion and wide, pale green eyes of Ruby. In fact, in recent months a passing expression or angle of Cleo’s face will bring Viv’s dead sister back so vividly that it sometimes makes her heart stumble. Perhaps that’s what’s behind the occasional frost she detects in her mother’s tone when she talks to her granddaughter: perhaps pain is at its root; the three of them have always been so close, after all.

Stella’s landline rings and she picks it up to embark on a long and involved conversation about a mindfulness workshop she’s hosting, and a few minutes later a young woman comes in, dark-haired and painfully thin, her small awkward frame a collection of sharp angles clothed in black. She startles at the sight of Vivienne, her eyes darting from her to Cleo with a look of panic as she backs away. ‘No, please don’t go,’ Viv says gently. ‘Are you OK? Would you like something?’

The woman plucks anxiously at her skirt. ‘No. I …’ She turns to leave, but just then Stella hangs up the phone and goes to her. ‘Jenna, how are you feeling?’ She puts an arm around her. ‘Headache gone now, is it?’

Visibly relaxing, she looks at Stella gratefully. ‘Yes, thank you,’ she whispers. ‘I thought I’d make a cup of tea.’

She has that effect on people, her mother, on the waifs and strays that she collects, has always collected, in one way or another. They all adore her. Even before she turned this house into a refuge, they would find her, seeking her out, sensing within her a place of comfort and safety. Viv watches as the young woman is steered towards the kettle, Stella’s hand upon her shoulder.

Cleo looks up to check that her mother’s attention is elsewhere, then turns back to her phone. It vibrates to indicate there’s a new message, and her heart leaps.

Cleo?

Hey.

Hey. Where were u yesterday? Missed u.

She stares at the words in surprise. He’s never said anything like that before. Had to do something with Mum, she writes.

K. Wot u up 2?

Nothing much. Homework.

She beams back at the little smiling face. They met on a Fortnite board on a gaming site a few months back. It’s only recently they’ve begun private messaging. His name is Daniel and he’s a year older than she. He’s told her he lives near Leeds and she’s told him she’s in London. Yesterday he sent her a picture of himself – a blond-haired boy smiling shyly beneath a beanie hat – and she’s been thinking about him ever since.

U there?

Yeah.

Thought I’d scared U off wiv my pic. Lol.

Course not. It’s nice.

Thanx. U got one?

She hesitates, but nevertheless her thirteen-year-old heart feels a thrill of excitement. Maybe, she writes. She glances at her mum, sees that she’s watching her, and hastily drops the phone.

‘Who’s that you’re texting, love?’

‘Just Layla.’ She’s a bit scared how easily the fib trips off her tongue. She doesn’t usually lie to her mum, or that is, only about how many sweets she’s had, or if she’s got any homework to do. But her mother only nods and turns back to the weird thin lady who looks terrified of everything.

Cleo knows she’s not got much time. She wants to give him something more and quickly writes, Gtg, spk 2mrw and then, before she can stop herself, she adds a then stares at it in horror. Why did she do that? Seriously, why? That’s not cool. That’s so babyish, so … and then he’s replied. And he’s put a too and she grins in relief.

‘Come on,’ her mum says to her, handing her her coat. ‘It’s time to go.’

Viv watches her daughter gather her books with painful slowness and tries to hide her agitation. She can hear Shaun’s voice from somewhere above, a door opening and then closing again, the sound of footsteps on the stairs. She resists the urge to drag Cleo away, her coat half hanging off her.

It happened a few weeks ago. Stella had gone away on a weekend yoga retreat and, as Cleo was on a rare visit to her father’s, had asked Vivienne to look after the house and guests in her absence. She’d been doing the books for the café at the kitchen table with a glass of wine when Shaun appeared.

He’d been staying there for a month by then, but they’d never made much more than small talk before. She tried to remember what Stella had told her about him: a recent spell in rehab for drugs, she thought. He had walked into the kitchen and stopped when he saw her, then leaned against the fridge, appraising her, a rather cocksure smile upon his face. ‘You in charge of the asylum tonight then?’ he’d asked.

She’d laughed. ‘Something like that.’

He sat down opposite her then, and she was slightly taken aback by his sudden proximity. He was tall and well built, with a broad Mancunian accent and was, she would guess, in his late thirties, tattoos covering his muscular arms, a somewhat belligerent air.

She’d looked back at him levelly. ‘So, how’re you finding it here? Settled in OK?’

He shrugged. ‘Yeah, it’s sound. Your mum’s all right, ain’t she?’ He stretched and yawned, the hem of his T-shirt rising up to reveal a flash of taut stomach. ‘She’s a character, any rate. Looks like a right old hippy and talks like the queen. What is she, some kind of aristo, slumming it with the proles?’

Viv had smiled and murmured a non-committal, ‘Hardly.’ The fact was, Stella’s parents had most certainly been wealthy, but Viv had never met them. Stella had been estranged from them since before she was born, and her and Ruby’s childhood had been anything but privileged.

‘Well, any road,’ Shaun said then, ‘knows what she’s about, don’t she?’ He nodded at her ledger book. ‘What you doing there, then?’

So Vivienne had told him about her café.

‘Done all right for yourself, haven’t you?’ Though he’d been smiling, there was a hint of resentment in his tone. He’d pulled out a tin of tobacco, begun rolling a cigarette, and started telling her about his misspent youth in Manchester. He was entertaining; funny and quick-witted, though she sensed this was a well-worn charm offensive, that there was an unpredictability hiding behind his smile and his mood might change in an instant. She’d met men like him before. She had, too many times in her youth, slept with men like him before, the sort whose swagger and bravado was a front for damage and gaping insecurity, who triggered her instinct to appease, pacify and bolster.

He was exactly the sort of man, in fact, that she had trained herself to avoid. ‘Your problem is, you go for lame ducks,’ Samar told her once. ‘It’s your saviour complex. You must get it from your mother.’ It was unfortunate that Shaun was so very good looking.

He had just finished telling her about how he and his school friends had stolen a milk float when suddenly he’d disarmed her by saying, ‘You’re one of those women who don’t know how fit they are, aren’t you?’

And it was so clichéd, such an obvious line, yet even as she’d rolled her eyes she’d felt a reluctant thrill. Probably because she’d recently turned forty and no one (apart from Walton) had said anything even vaguely complimentary to her for quite some time. And she hated herself for it, saw by the flash in his eyes that he’d seen his words had hit their mark, and if she’d drunk a little less wine, or been a little less giddy at finding herself childfree for the first time in months, she might have put him firmly in his place.

Instead she’d laughed, ‘Oh do me a favour,’ and he’d grinned back at her, the air altering between them, both of them knowing now what the score was. She’d poured herself another drink, enjoying the back and forth of flirtation, telling herself it would only go so far: she would finish her wine then go upstairs to bed, alone. But, of course, it didn’t happen quite like that.

And when she’d woken up the next morning in his bed she’d been full of self-loathing and regret. Sleeping with Stella’s guests was about as stupid as it got, and her mother would be furious if she found out. She’d slipped from the bed, silently scooping up her clothes and escaping to Stella’s room – where she was supposed to have slept that night. Knowing that her mum was due back later that afternoon, she’d fled for home as soon as she could, before Shaun even had time to surface.

She’d managed to avoid him for a while after that and life had gone on, though she’d shuddered whenever she thought of him. She’d only just begun to forgive herself, to hope she’d got away with it when, unexpectedly, he’d called her.

She’d answered her mobile as she was rushing to fetch Cleo from a party.

‘All right, Viv. How’s tricks?’

‘How did you get my number?’ she asked, before remembering with a sinking heart that it was pinned to the corkboard in her mother’s kitchen, the ‘in case of emergencies’ contact for when Stella was out.

‘Well, that’s not very friendly, is it?’

‘Sorry. I …’

‘Wanted to know if you fancied a drink.’

‘Um, I’m not sure that’s a good idea,’ she’d replied slowly.

‘Oh, right, like that is it?’ His voice was instantly hard, the fragile ego she’d sensed lurking there revealed in a heartbeat.

‘No, of course not,’ she’d said hastily. ‘I’m just not … I’m sorry, but I don’t want to get into anything, we probably shouldn’t have …’

He’d given a belligerent laugh. ‘Think you’re too good for me, is that it? Should have been grateful, saggy old bitch.’ His sudden aggression had stunned her. He’d cut her off, leaving her to stare down at her phone, her heart pumping with shock and anger.

That had been two weeks ago. She’d not seen him since, had managed to avoid coming to her mother’s house until today. But as she and Cleo finally get to the door, Shaun appears at the top of the stairs. He stops, looking her up and down insultingly, and she feels a flash of cold dislike.

‘Going so soon?’ he says, sauntering down towards her.

She puts her hand on Cleo’s shoulder and steers her towards the door. ‘Yep, gotta run. Bye.’ She and Cleo go out into the night, and she closes the door firmly behind her, a shiver of disgust prickling her skin.

Their house is a twenty-minute walk from Stella’s, on the other side of the Rye, and Vivienne pushes Shaun from her thoughts as she links her arm through her daughter’s. ‘How was school today, love?’ she asks.

For a while they chat about a history project Cleo’s been working on and how she thinks her team will do in an upcoming football match, and Viv smiles down at her, her happy, popular child, always tumbling from one enthusiasm to the next. She’d been twenty-six when she’d become pregnant, a result of a brief and unhappy fling with one of the suppliers for her café, a handsome but feckless Irishman named Mike who was a few years younger than herself. He’d run a mile at the news of her pregnancy and had kept only sporadic contact with his daughter since. It had always been the two of them after that, and as a result they’d always been close – as close as Viv was to her own mother, in fact.

As they draw nearer to their street Vivienne shivers in the cold November night and murmurs, ‘Thank God it’s Friday. I can’t wait to get home. We’ll have spaghetti for tea, shall we?’

They pass beneath a street lamp just as Cleo looks up at her and smiles, and there is, again, something in the angle of her face, in the expression in her eyes, that takes Viv’s breath away. Her daughter looks in that split-second so exactly like Ruby that her sister is brought back to life with sudden, shocking force.

It’s a new thing, Cleo’s random expressions triggering this heart-jolting reaction in her. Out of the blue a memory will turn up, glinting and sharp, to stop Viv in her tracks. Tonight she’s transported back to the little house in Essex where she and Ruby spent their childhood, a white, ramshackle cottage on the edge of a stretch of fields. In this memory Ruby is sixteen and heavily pregnant, dressed in a blue cotton dress and standing by the window that’s crisscrossed with iron latticing, the light falling on her red-gold hair, her hand resting on her swollen belly.

Viv, aged eight, had gone to her sister and pressed her cheek upon her tummy, gazing up at her as she listened intently. And then it happened: as Ruby smiled down at her with the exact same expression that she’ll see mirrored in her own daughter’s face thirty-two years later, Vivienne felt something move beneath her cheek and squealed in excitement. ‘Did you feel that?’ she asked. ‘I felt him! I felt the baby kick!’

And Ruby grinned and said, ‘Yes, I felt it too. Not long to go, Vivi. Two weeks and you’ll be an auntie.’ An auntie at eight years old! How important and grown-up and wonderful that felt. She would love this baby with all her heart; she did already.

But she never got to meet her sister’s child, never had a chance to call him by the name Ruby had so carefully chosen. Noah. Her nephew would have been called Noah. Because almost two weeks later, a few days before her due date, Ruby would be dead, and Noah with her.

Now, walking along the dark street with her own child, a passing motorbike rouses her from her thoughts. Seeing that they’ve nearly reached their gate she swallows back the shards of pain that have risen to her throat. ‘Come on,’ she says to Cleo, opening the door. ‘Go and get changed and I’ll make dinner, then we’ll watch something on Netflix, shall we?’

Alone in the kitchen, she puts the radio on and pours herself a glass of wine. She hates it when this mood descends upon her. It’s the anniversary of Ruby’s death on Monday and it always upsets her, no matter how prepared for it she is. Noah would have turned thirty-two this year, and as she has done every single year since it happened, she imagines the person he might have become – from toddler, to schoolboy, to teenager and young man – a sadness gathering inside her that’s hard to shake off. ‘Come on, Viv, get a grip,’ she tells herself and, tuning the radio to a music station, she turns the volume up, then starts to put together the ingredients for spaghetti bolognese.