Читать книгу Vertical Motion - Can Xue - Страница 7

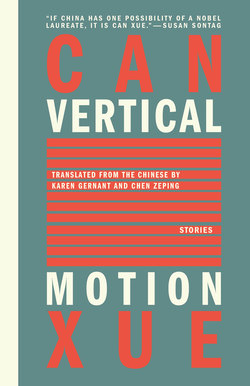

Vertical

Motion

Оглавление=

We are little critters who live in the black earth beneath the desert. The people on Mother Earth can’t imagine such a large expanse of fertile humus lying dozens of meters beneath the boundless desert. Our race has lived here for generations. We have neither eyes nor any olfactory sense. In this large nursery, such apparatus is useless. Our lives are simple, for we merely use our long beaks to dig the earth, eat the nutritious soil, and then excrete it. We live in happiness and harmony because we have abundant resources in our hometown. Thus, we can all eat our fill without a dispute arising. At any rate, I’ve never heard of one.

In our spare time, we congregate to recall anecdotes of our forebears. We begin by remembering the oldest of our ancestors and then run through the others. The remembrances are pleasurable, filled with outlandish salty and sweet flavors, as well as some crispy amber—the immemorial turpentine. In our recollections, there is a blank passage that is difficult to describe. Broadly speaking, as one of our elders (the one with the longest beak) was digging the earth, he suddenly crossed the dividing line and vanished in the desert above. He never returned to us. Whenever we remembered this, we fell silent. I sensed that everyone was afraid.

Even though people never descended to our underground, we actually gained all kinds of information about the mortals above us. I don’t know what sort of channel this information came from. It is said that it was very mysterious, and that it had something to do with our builds. I’m an average-sized, ordinary individual of my genus. Like everyone else, I dig the earth every day and excrete. Recalling our ancestors is the greatest pleasure in my life. But when I sleep, I have some odd dreams. I dream of seeing people; I dream of seeing the sky above. Human beings are good at movement. They feel bumpy to the touch. I’m extremely jealous of their well-developed limbs, because our limbs have atrophied underground. We all move about by wiggling and twisting our bodies. Our skin has become too smooth, easily injured.

We make these kinds of remarks about humankind:

“If you approach the border of the yellow sand, you can hear camel bells ringing: this is what our grandfather told me. But I don’t want to go to such a place.”

“Human beings reproduced too quickly: it is said that their numbers are immense. They’ve consumed all of earth’s food, and now they’re eating yellow sand. It’s dreadful.”

“If we don’t think about the sky and the people on earth, doesn’t that ultimately mean that those things don’t exist? We have enough memories and knowledge of this kind of thing. It’s pointless to go on exploring.”

“The yellow sand above us is more than ten meters deep. It’s just like the end of the world to those of us who live in the warm, moist, deep soil. I’ve been to the boundary and have felt the desire to thrust upward. Here and now, I’d like to recall that time.”

“Our kingdom of the black earth didn’t always exist. It came into being only later. Our oldest ancestors didn’t always exist, either. They, too, came into being only later. And so here we are. Sometimes I think that maybe one of us should take a risk. Since we came from nowhere, taking risks is part of our obligation.”

“I want to take a risk, too. I’ve begun fasting recently. I hate my sweaty, damp, and slippery body. I want a change. Whenever I think of yellow sand dozens of meters deep, I’m terrified. But the more terrified I am, the more I want to go to that place. There, I would certainly lose all sense of direction. Probably my only sense of direction would come from gravity. But would gravity change in such a place? I’m very worried.”

“We remember all of the history and all of the anecdotes. Why have we forgotten only our long-beaked grandpa? I always feel that he’s still alive, but I can recall nothing about him. Recollections concerning each of us are preserved only in our hometown. Once one leaves here, one is thoroughly invalidated by history.”

“When I grow quiet, whimsical ideas come into my mind. I would like our collective to ease me into oblivion. Yet, I know this can’t be done here. Here, my every word and action will be preserved in everyone’s memories, and will be passed on from generation to generation.”

“I think I can grow bumpy skin; I just have to make a point of exercising every day. Recently, I’ve been rubbing and scraping against the rigid clods in the earth. After my skin bleeds, scabs form. It seems this is working.”

It’s worth pointing out that we critters don’t congregate in a certain space for our meetings (as the human beings above us do), for our kingdom of the black earth has no spaces. Everything is packed together. When we do assemble for recreation or discussion, the earth still blocks us off from each other. The black earth is a very good medium for transmitting sound. Everyone can hear every single one of our utterances, even if it’s in the feeblest voice. Sometimes while we’re digging, we accidentally run into another body. At such times, both sides may feel really disgusted. Ah, we really don’t care to have any bodily contact with our own race! It’s said that the people above us had to have sexual intercourse in order to propagate: this is much different from our asexual reproduction. Indeed, what does sexual intercourse look like? We don’t yet have any detailed information about this. Sometimes when I think of being entangled with my own kind, I start squealing from nausea.

=

When we stop digging, we don’t move. We’re like pupae as we dream in the black earth. We know that our dreams are similar, but our dreams have never been strung together. Each of us has his or her own dreams. During those long dreams, I can bore deep into the earth and then fuse into a single body with the earth. In the end, my dreams are about only the earth. Long dreams are great, for they are sheer relaxation. But if this goes on for a long time, I feel vaguely discontented, because a dream of earth can never give me the joy that I most want to experience.

Once, we gathered together and talked of our dreams. After I related one of mine, I began crying in despair. What kind of dream was it? It was blacker and blacker until finally it became the black earth. In my dream, I wanted to make a sound, but my mouth had vanished. One after another they consoled me, referring to our ancestors to prove nothing was wrong with our lives. I stopped crying, but something ice-cold settled into my body. I thought it would be difficult to hang onto my previous optimistic attitude toward life. Subsequently, even during working hours, I could feel the heavy black earth pushing down on my heart. Even my rigid beak was weakening, and it itched now and then. I wanted the relaxation that comes from dreaming, but I didn’t want the fatigue that comes after waking from a dream. I didn’t want to lose interest in life. I must have been possessed. Was I going to disappear in the boundless yellow sand just as our missing ancestor had?

I had recently lost weight, and I was sweating a lot—more than usual. Perhaps because of my mood, I was about to fall ill. When I dug the earth, I heard my companions encouraging me, but for some reason this didn’t cheer me up. Instead, I felt sorry for myself and was sloppily sentimental. At break time, an elder talked to me of my late father. He had a lovely buzzing voice, much like the sound sometimes made by the black earth. I called that sound a lullaby. The elder said my father had had a last wish, but he’d been unable to express it. Those beside him didn’t probe, either, and thus his last wish hadn’t been preserved in our memories. Near death, my father made an odd sound. This old man had been nearest to him, so he heard the sound the most distinctly. He understood immediately that my father wanted to fly like a bird in the sky.

“So did he want to become a bird?” I asked.

“I don’t think so. He had a higher purpose.”

I talked with the elder for a long time about what my father’s last wish might have been. We spoke of sandstorms, of giant lizards, of a certain oasis that had existed, and also of certain minor disturbances involving our ancestors in remote antiquity—because a qualitative change in the earth brought about a scarcity of food. Each time we broached a new topic, we felt we had almost reached my father’s last wish. But as we continued talking, it eluded us even more. It really made us uneasy.

Thanks to the elder’s information, I gradually calmed down. After all, there was a last wish! This made me feel less nihilistic.

“M! Are you digging?”

“Ah, I am!”

“That’s good. We’ve all been worried about you.”

These dear friends, associates, kin, and confidants! If I didn’t belong to them, who would I belong to? The hometown was so serene, the soil so soft and delicious! I felt that I became a better self. Although my chest still ached dully, the disease had left me. This didn’t mean, however, that I was unchanged. I had changed. Hidden in me now was an obscure plan that even I couldn’t explain.

I was still like everyone else—working, resting, working, resting . . . I heard subtle transformations taking place in our hometown. For example, the tribes decreased in number; the desire to procreate declined; unreasonable complaints spread among us; and so on. Recently, we had begun to amuse ourselves by measuring the lengths of our beaks with the width of our atrophied fingers. “Ha, ha! Mine is three fingers long!” “Mine is four!” “Mine is even longer—four and a half!” Even though our fingers weren’t the same width, this activity was still fun for everyone. I discovered that my beak was longer than those of all of my brethren. Was it possible that the elder who had disappeared was my great-grandfather?! Because of my discovery, I broke out in a cold sweat and kept this secret to myself.

“M, how many fingers is your beak?”

“Three and a half!”

I kept my body vertical and continued rushing upward. Everyone soon discovered this change in my motion. I felt the fear all around me. I heard them say: “Him!” “Scary, scary!” “I feel the land wobbling. Will there be an accident?” “M, you need to get hold of yourself.” “It isn’t in our nature to move straight up!”

I heard all of this. I was engaged in a dangerous activity and couldn’t stop this impulse. I ascended, ascended—until, worn out from this work, I slept a dreamless sleep. It was a sound sleep—like death. It was free of confusion and anguish. And I couldn’t estimate how long I had slept. After I awakened, my body once more rushed up. This had become a conditioned reflex.

=

Before long, I noticed a deathly silence all around me; they were probably deliberately staying away from me. Because I was far from the border, others must have been here, too. For the first time in my life, I was alone in an absolutely quiet place. Two large things—black, certainly blacker than the earth—settled over my head all the time. I thought those two things must be heavy and impenetrable. The bizarre thing was that as I kept digging upward, they kept backing off. I couldn’t touch them. If I touched them with my beak, would we be together for all eternity? Sometimes, they fused into one huge thing and sometimes they separated again. When they were fused together, they made a gege grinding sound; when they were separated, they moaned unhappily. I couldn’t think about so many things: I just continued darting ahead as though they weren’t there. I thought, I wasn’t supposed to die so soon. Was I perhaps implementing my father’s last wish?

More time passed, and I was working in the deathly quiet and sleeping soundly in the deathly quiet. Scrupulously controlling my feelings so as not to think too much, I knew I was approaching the boundary. Ah, I nearly forgot those two black things! Did I take them to be myself? It was obvious that one could become accustomed to anything. To be sure, I was also sometimes weak, and at such times, I would utter a heartfelt lament: “Father, ah, Father, your last wish is such a terrifying black hole!” This lament gave rise to a misconception: the layers of black earth were twisting me, as if they would twist off my body. I also felt that my ancestors’ corpses were hidden in the earth’s folds. The corpses emitted spots of phosphorescence. I never hallucinated for very long: I didn’t like sentimentality. Most of the time, I ascended step by step. Ascended!

Since beginning vertical motion, I felt that my life was more disciplined—work, sleep, work, sleep . . . Because of this regularization, my mind was also transformed. In the past, I loved to have rambling daydreams—about the layers of black earth, about the ancestors, about Father, about the world above, and so forth. Daydreaming was a way to relax, a kind of entertainment, a kind of tasty turpentine. Now everything had changed. My daydreams were no longer rambling; now they had an objective. As soon as I began resting, those two black things above me started suggesting a direction, and they towed my thoughts in that direction. What was above? Simply those two things. As I was musing, I heard them make the bizarre sound of a watchman’s wooden clapper: it was as if someone were striking clappers on an ancient mountain on the ground above and the sound actually reached us underground. Listening attentively, I was thinking of the huge black things. While I was enthralled in this, the sound of the clapper would suddenly stop and become the sound of us insects—many, many insects—boring into the ground. Sometimes I also heard the obscure sound of insects talking—a sound that I seemed to have heard before. Ah, that sound! Wasn’t it the very sound that I had heard not long after I split away from my father’s body? It appeared that Father was still among us. He brought me a sense of stability, confidence, and a kind of special excitement. A new realm of imagination lay in this. I realized that I liked my present life. When you were about to achieve your objectives, when you incessantly extended your beak toward the things that interested you so much: Didn’t you feel happy? To be sure, I didn’t think of this too much: I merely felt satisfied with my new circumstances.

I realized tardily that the two black things above were not just totally black, but they contained infinite hues that were in constant flux. The closer I came to the boundary, the weaker and flimsier the core parts seemed to be, as if they would pass through light. Believe me, my body was close to sensing light, which was pink and a little hot. Once, when I overexerted myself, I felt I had torn one of the cores. I even heard a breaking sound—cha. I was both excited and afraid. But after a while, I realized that nothing had happened: they were still above me. All was well. I was being silly: How could there be light underground? Now these two things were so exquisite, so seductive. Wasn’t Father’s obscure voice echoing once again?

=

Before long, something happened: while I was digging upward, there was a sudden landslide. It was only afterward that I concluded it was a landslide. At the time, I realized only that I was falling and I didn’t know where I had fallen. I remember that at first I’d been excited and had faintly heard the noise that was told of in our ancient legends: the sound of people above congregating for singing and dancing. At the time, I thought, How can there be a congregation in the desert? Or perhaps it wasn’t a desert over us, after all? Now, the two black things above me really did let light through. I am speaking merely of my conclusion, because I wasn’t aware of it. This light wasn’t pink, nor was it yellow or orange. It was a thing that you couldn’t sense, wedged between the two black things. The sound of the musical accompaniment became increasingly intense, and I grew increasingly excited. I exerted all of my strength to thrust upward . . . and then there was the landslide.

I was despondent, for I thought I had certainly fallen to the place where I was before I started my vertical motion. But a long time passed, and silence still lay all around me. Did another kingdom lie beneath the desert, a dead kingdom? It was very dry here, and the earth was not the black earth of before. All of a sudden, it came to me: this wasn’t earth, it was sand! Right. This was shapeless sand! I had clearly fallen down, so how had I ended up in this kind of place? Could gravity have changed direction? I didn’t want to think about this too much. I had to start my work as soon as possible, for it was only work that could put me in a good mood with a steady self-confidence.

I began digging—still in the upward, vertical motion. Motion in the desert was quite different from motion in the earth. In the earth, you could sense the track—and the sculpture—your motion left behind. But this heartless sand submerged everything. You couldn’t leave anything behind, and so you couldn’t judge the direction of your motion. Of course, with my present lifestyle, vertical motion was just fine, because my inner body was attuned to gravity. As this went on, I felt that this work was harder and tenser than before. And what I ate was sand: flavor was out of the question. I ate it just to fill my stomach. I was tense because I was afraid of losing my direction by mistake. I had to keep paying attention to my sense of gravity: it was the only way to maintain the vertical route. This sand would seemingly choke all of my senses. I had no way to know if I was even in motion. And so my feelings shrank inward. There was no longer a track, not to mention the sculpture, but only some blurred throbbing innards, along with flashes of faint light in my brain.

And so, was I squirming in the same spot or was I moving up? Or sinking down? Was I capable of determining this? Of course not. Every so often I made expanding and contracting motions, which I thought meant I was moving up. Of course the sand’s resistance was not nearly as great as the earth’s, but this slighter resistance left me uneasy. If you have nowhere to stand, then you have no way, either, to confirm the results of your exertions, and there’s likely to be no result. After tiring from my activity, I ate some sand and then fell into a death-like sleep. After my skin cracked, it healed again, and after healing it cracked again. Little by little, it was thickening. The humankind above me wears thick skin. Had they all gone through what I was experiencing? Ah, this quiet, this desolation! One can probably endure it for a short time, but if it persists, isn’t it the same as being dead? Uneasiness germinated tardily in my mind. I reflected on the one who had disappeared: Perhaps he was still alive? One possibility was that he and I were both living and that we would never actually die. Buried by this boundless yellow sand, each of us leapt on his own, and we would never be able to see each other. When I considered this possibility, I began twitching all over. This occurred a number of times.

The last time it happened, it was really dreadful. I thought I would die. I became aware of the mountain, which was the two black things that had formerly been above me. After disappearing for a time, they had returned. They pressed down toward me, but didn’t press me to death. They were just suspended above. At this time, I stopped having spasms at once. As this eased, at first my consciousness functioned rapidly, and then it was entirely lost. I leapt up with all my strength! At once, the mountain weakened so much that it was like two leaves—leaves of the phoenix tree above ground. Indeed, I sensed that they were drifting. As I saw it, a miracle was taking place. In my excitement, I leapt again, and now there were four phoenix leaves! There were actually four. I heard the sound of each one. It was the metallic sound mentioned in legends. I knew I hadn’t lost my way: I was on the correct path! Soon, the metallic leaves would split and I would see light! Although I had no eyes, this wouldn’t preclude my “seeing.” I—an insect underground—would see light! Ha ha! Not so fast. How would I do this? With my scarred, haggard, restless body? Or was it just my mirage? Who could guarantee that the instant I emerged from the earth wouldn’t be the moment of my death? No, I didn’t want to get to the bottom of this question. It would be fine if I could just keep sensing the phoenix leaves above me. Ah, those eternal metallic leaves: the cool breeze on Mother Earth shuttled among the leaves . . .

I fainted. When I came to, I heard sand buzzing all around me, and in this sound an old, low voice spoke:

“M, is your beak still growing?”

Who was it? Was it he? Who else could it be? So much time had passed. This desert, this desert . . . How could things be like this?

“Yes, my beak, my beak! Please tell me: Where am I?”

“You’re on the uppermost crust of the earth. This is your new home.”

“Can’t I bore my way out of it? Are you saying that from now on I can only wander around in this sand? But I’m accustomed to vertical motion.”

“You can only engage in vertical motion here. Don’t worry, there’s more sand on top of this sand.”

“Are you saying I cannot break out completely? Oh, I see. You’ve tried it. How long have you lived in this region? It must be a very long time. We can’t measure the time, but we know we lost you long ago. Dear ancestor, I never imagined, never imagined that in this—how to say it?—that in this extremity, I would come across you. If my father . . . ah, I can’t mention him. If I do, I’ll faint again.”

He didn’t say any more. I heard his far-off voice: cha, cha, cha . . . as he dug the sand with his long, senile beak. My bodily fluids were boiling. It was bizarre: I’d stayed in such an arid place for so long and yet I still had fluids in my body. Judging by the sound I heard, this ancestor had fluids in his body, too. This was really miraculous! Somewhere above me, he walked away. He must have seen the phoenix leaves, too.

Ah, he returned! How wonderful—now I had a companion! I had someone to communicate with. The boundless yellow sand was no longer so frightening! Who . . . who was he?

“Grandpa, are you the one who disappeared?”

“I am a wandering spirit.”

This was great: I spoke, and someone answered me. How long had I been without this? Someone of the same species would engage in the same activity and live with me in this desert . . . Father’s last wish was for me to find him: I realized this!

=

I was a little critter submerged in the desert. This was the outcome I had pursued. In this mid-region, I was envisioning the phoenix leaves on Mother Earth. Yet, I didn’t forget my kindred in the dark.