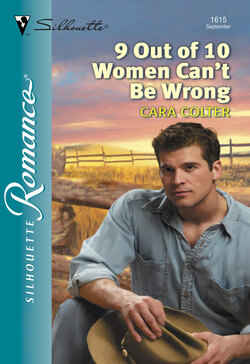

Читать книгу 9 Out Of 10 Women Can't Be Wrong - Cara Colter - Страница 12

Chapter One

ОглавлениеTyler Jordan was aware he was being watched.

There it was again. The secretary, a woman old enough to be well beyond such nonsense, glanced up coyly from behind her work, looked at him longer than he considered strictly polite and then, with the flash of a secretive smile, looked back to her computer screen.

Ty pretended he hadn’t noticed her scrutiny and studied the room uncomfortably. The outer waiting area of Francis Cringle and Associates struck him as being more like the kind of office he’d seen in the rare movie he watched than like a real life office, or at least not any real life office he’d ever been in.

He couldn’t believe his sister—a girl born and raised on a ranch—worked in a place like this…actually fitted in here.

He was sitting on a sofa of butter-yellow leather. Another faced him. Huge deep-green plants were scattered throughout. He wasn’t sure how a real plant survived in an atmosphere with no natural light. The artificial lighting was muted; the rug, covering marble tiles, looked old and worn in a way that convinced him it had been picked up at an African bazaar.

He heard the quick tap of heels coming down the hallway outside this posh office and felt himself tensing.

If whoever it was went on by, then he knew he must be imagining all the unusual attention he was getting. But no, the tapping of the heels slowed, and then she came in. Tall and willowy, in a tight blue skirt and a short matching jacket, she glanced quickly his way, her confidence astounding, given the balancing act she must be doing on those high stiletto heels, then moved over to the desk and had a whispered conversation with the woman there. The conversation was punctuated with breathless giggles and sidelong looks.

At him.

The looks were loaded with secrets…and satisfaction. Looks not at all in keeping with the muted atmosphere of subdued professionalism that the well-known public relations firm’s office had achieved.

Ty frowned and picked up a magazine off the dark-walnut coffee table in front of him. He caught a glimpse of his reflection in the highly polished surface, and it confirmed how out of place he was here. Cowboy hat, white denim shirt unbuttoned at the throat, jeans. He might have raised some of the cattle that provided the luxurious leather he was now sitting on.

A flurry of giggles and looks made him scowl at the magazine, flip it open and read the first paragraph of an article on office management.

He didn’t have an office, but looking at the article seemed preferable to pulling his cowboy hat even further over his eyes.

Another young woman flounced into the office, pudgy and cute, took a long look at him, then flung her blond hair over her shoulder, fluttered her eyelashes several times. If she was expecting a response, he didn’t give her one, and she hurried over to the desk and joined the other two in whispered conversation.

Which he heard snatches of. Something about being even better in person, something about people who should be sharing hot tubs and wine on starlit nights, something about crackers in her bed. He sent them a dark and withering look that had the unhappy result of eliciting sighs and a few more giggles.

He gave up pretending the article interested him, tossed down the magazine, stretched out his legs and crossed his cowboy boots at the ankles. He looked wistfully at the door.

His eyes drifted to the clock. Five more minutes and he was leaving. He didn’t care what kind of pickle Stacey had gotten herself into this time. At the moment he would be no help to his kid sister, anyway, since he felt as if he’d like to throttle her.

A one-and-a-half-hour drive into the center of Calgary. At calving time. Because she had an emergency. Life-and-death, she’d claimed on the phone.

So, if it was so life-and-death, where was she?

And if it was so life-and-death why had she asked him to not wear jeans with holes in them? And clean boots? What kind of person in a life-and-death situation thought of things like that?

Life-and-death meant the emergency ward at the hospital, not the outer office of Francis Cringle.

So here he was in pressed jeans and a clean shirt and his good boots and hat, being giggled at, and his sister was nowhere to be seen.

He resisted, barely, the impulse to send the secretaries into more conniptions by rubbing his back, hard, up against the wall behind him.

“Ladies, do you have business elsewhere?”

They scattered like frightened chickens in front of a fox, and his rescuer, a tall woman, distinguished, turned and looked him over, carefully. “Tyler Jordan?”

He practically leapt to his feet, took off his hat and rolled it uncomfortably between his fingers. “Ma’am?”

She smiled when he said that. That same damned smile he’d been seeing since he’d walked into this stuffy office!

“Will you come with me, sir?”

Sir. A phrase he’d heard rarely. Usually in restaurants where he was destined to use the wrong fork. He followed her down the hall, having to cut his long stride so that he didn’t walk on top of her.

She ushered him into an office, smiled again and shut the door behind him. The light pouring in the floor-to-ceiling windows on two walls blinded him momentarily after the dimness of the outer office.

But when his eyes adjusted, he registered more opulence, and Stacey. She was sitting in a chair on this side of a huge desk that looked as if it was made of solid granite.

“Hi, Ty,” she said with a big smile, and patted the seat of the empty chair next to her. “How’s my big brother today?”

If they didn’t have an audience, a wizened old gnome of a man sitting behind the desk, Ty would have given her the complete and unvarnished truth. He was irritated as hell today.

Life-and-death, indeed.

His little sister had never looked healthier! Her mischievous eyes sparkling, her dark hair all piled up on her head making her look quite sophisticated, wearing a suit and shoes just like all the other women he’d seen today.

“I’ve had better days,” he answered her gruffly, and reluctantly took the chair beside her. More leather. His boots sank about two inches into the carpet.

“I suppose you’re wondering what’s going on?” she asked brightly.

“Life-and-death,” he reminded her.

“Ty, this is my boss, Francis Cringle. Mr. Cringle, my brother, Ty.”

Ty rose halfway out of his chair, took Cringle’s hand and was a little surprised by the strength of the grip.

“A pleasure to meet you, Mr. Jordan,” the voice was warm and friendly, the voice of a man who had spent a lifetime promoting items people had no idea they needed. “Thanks for coming. Stacey tells me you’re a busy man. She also mentioned you have no idea why you’re here?”

“None.”

“Your sister entered you in a contest. And you won.”

A contest. Ty shot his sister a menacing look. Life-and-death, huh? Knowing his sister, he’d won something really useless like a lifetime supply of jujubes or a raft trip down the Amazon in the hot season.

“You see, Ty.” Stacey was talking very quickly now, catching on that she was trying his patience. “Francis Cringle has been hired by the Fight Against Breast Cancer Fund to do their next fund-raiser.”

Breast cancer. How he hated that disease, the disease that had stolen the life from his mother, left a whole family shaken, marooned, like survivors of a shipwreck. Only their shipwreck had dragged on endlessly. Five years of hoping, being crushed, hoping again.

“Okay,” he said, not allowing one single memory to shade his voice, “And?”

“You remember my friend Harriet don’t you?”

“How could I forget?” Harriet Pendleton was a young woman his sister had met at college and brought home for a week one spring. What? Three years ago? Four?

Usually he couldn’t distinguish Stacey’s friends one from the other. But Harriet was the girl most likely to be mistaken for a giraffe. Nearly six feet tall, most of that legs and neck, she was covered in ginger-colored freckles and splotches that matched untamable hair. Her eyes, brown and worried looking, had been enlarged by thick glasses. Her quick, nervous smile had revealed extremely crooked teeth.

Totally forgettable in the looks department, not that Ty ever paid much attention to Stacey’s friends, Harriet had made herself memorable in other ways. Disaster had followed in the poor girl’s wake. She had broken nearly everything she touched, run the well dry by leaving a tap on and let the calves out by not securing a latch properly.

Somehow they’d gotten through the week before Harriet managed to stampede the cattle and burn down the barn, but they had sent her home with her arm encased in plaster.

He should have been glad to see them go, and yet even now he could feel a little smile tickle his lips when he thought of Harriet.

She had made him laugh. And even though he always felt lonely for a week or two after Stacey had been home for a visit, that time it had taken even longer to get back to normal.

“Lady Disaster,” Ty remembered. “I thought you told me she lived in Europe now.”

Stacey gave him that do-you-listen-to-a-word-I-say look. “She’s been back for months. She’s the one who had the photograph that won the contest.”

“And how do I fit into all this? Life-and-death, remember?” He had a feeling they were moving farther and farther from the point, as if he was being swept away in the current of his sister’s enthusiasm. Unwillingly.

“I’m getting to it,” she said, her tone reproaching his impatience. “The fund-raising idea is to do a calendar. Everybody does them. You know, the firefighters for the burn unit and the police for the orphan’s fund.”

“I don’t know. Haven’t a clue what you’re talking about.”

She actually looked annoyed with him, the same way she did when she’d still been at home and mentioned a film or a popular song or some celebrity that he knew nothing about. She would roll her eyes at him and say, “Oh, the famous blank look from my brother, the recluse from life.”

Today she just handed him a calendar, called “Red Hot,” which he presumed he was supposed to look at. He flipped through it, without much interest, feeling resentful that he had a ranch to run and was sitting in Calgary looking at pictures.

Very dull pictures of guys without their shirts, in firefighter’s pants with suspenders. They looked self-conscious, which he didn’t blame them for, and they held a variety of unlikely poses that made their muscles bulge. A few had artfully placed smudges of soot on their cheeks and chests.

“People buy this?” he muttered incredulously. He thought of his own calendar at home. Posted beside his fridge, it had nice pictures of plump Herefords on each month. The Ranch Hand Feed Store gave the calendars away free in December. The Farm Corp Insurance Company also handed out free calendars. Ty had no idea people bought calendars.

“Women buy them,” his sister said, and he realized it shouldn’t surprise him that a woman would buy something she could get free. Women liked to spend money, a lesson his sister had taught him.

“They’re especially willing to buy calendars like these if it’s in support of a good cause. Like breast cancer research.”

Something in her voice made him look up. He stopped flipping pages between March’s Bryan and April’s Kyle and closed the calendar firmly. He slid it onto the corner of Cringle’s desk, remembering, uneasily, all the looks he’d been getting all morning.

He had the awful feeling he had not won a lifetime supply of jujubes. Not even close.

“What have you done, Stacey?”

“I entered you in the contest!” she admitted, her smile not even faltering. “Harriet had the most incredible photo. Francis Cringle and Associates held a contest to find the perfect calendar guy. And you won!”

The perfect calendar guy? Me?

“You mean you set it up for me to win,” he said tightly.

“Oh, no, Mr. Jordan,” Mr. Cringle interjected with swift authority. “Absolutely not. All the entries were done in a double blind. Your sister was not one of the judges.”

“Who were the judges?” he asked reluctantly, not really caring. He slid a look at the door, planning his escape route.

Mr. Cringle answered. “We set up the entries at a local mall for a week. Over two thousand women voted. Do you want to hear the strangest thing? Ninety percent of them voted for you. Ninety percent!”

He felt a sick kind of embarrassment at the idea of that many women ogling a picture of him. And he felt more than a little angry at his sister.

“The concept we’re working with,” Mr. Cringle told him, “is a one-man calendar. Different photos illustrating different real-life scenarios that man finds himself in. I was thrilled to hear you are a rancher. The photo opportunities are mind-boggling.”

Ty felt he should have boggled Stacey’s mind—or maybe her behind—when she skipped school in the tenth grade. And when she snuck out her bedroom window in the eleventh. He should never have allowed her to be so mouthy and strong-willed. He should have definitely drawn the line with her when she had begun to date that hippie. If he had managed to control her in any one of those circumstances maybe he wouldn’t be sitting here now.

Now, it seemed it was too late to straighten his sister out. Ty would just have to try and save himself.

“Mr. Cringle,” he said carefully, “I’m sorry. My sister has wasted your time. I’m not a calendar model, and I never will be. I’m a rancher. Despite what women who buy calendars might want to believe, there is nothing even vaguely appealing about the kind of work I do. I’m usually up to my ears in mud and crap.”

“Oh, Ty,” Stacey said, “it’s not as if the calendars come in scratch and sniff. Women love those kind of pictures. Sweat. Mud. Rippling muscles. Jeans faded across the rear. You’re perfect for the job, Ty.”

Ty was staring at his sister with dismay. Women liked stuff like that? And how the hell did she know? He realized he hated that she was a full-fledged adult.

“So, hire a model,” Ty said, and heard the testiness in his voice. “If you need some mud, I’ll provide it.”

“Models are so—” Stacey searched for the word, beamed when she found it “—slick.”

Ty could only hope she didn’t know that from firsthand experience.

“Mr. Jordan, I’m sure there were male models among the entries that were posted at the mall. The result of the competition tells me women can tell the difference between someone posing as a rugged, raw, one hundred percent man and the actual man.” Cringle regarded him intently, then said softly, “Ninety per cent is a whole lot of calendars.”

“Yeah, well.” Ty glared at his sister.

“Mr. Cringle, you leave him to me,” Stacey said brightly, but Ty noticed her eyes had tears in them. She’d better not even think she was going to change his mind with the waterworks thing.

It had worked way too many times before. That was part of the problem. Stacey knew exactly how to tug at his heartstrings.

The rest of the world probably thought he didn’t have a heart.

But his little sister knew the truth about him.

When she was seven their mother had died of breast cancer. A year later their father had been killed in a single-car accident, though Ty still wondered how accidental it had been. His father had become a shell of a man since his wife had died.

Ty had been eighteen when the accident occurred. Way too young to be thrust into the responsibility of bringing up a little girl.

But what choice had he had?

Ship her off to an aunt and uncle he barely knew? Let her go to a foster home? Not while he lived and breathed. There had been absolutely no choice. None. His sister had needed him to grow up fast, and he had.

“Why don’t we go have lunch together?” she said to him sweetly. “And we’ll meet Mr. Cringle back here at, say, one o’clock?”

Ty decided not to lay down the law with her in front of her boss. He got up, extended his hand again. “Mr. Cringle,” he said with finality.

But the man looked from him to his sister and back with a twinkle in his eye.

“Until we meet again,” Cringle said.

“Which, hopefully, will be never,” Ty muttered under his breath as he herded his sister toward the door.

“I don’t have time for lunch,” he told her in the hallway. “Calves are hitting the ground as we speak. And I’m not changing my mind about the calendar thing. Get it out of your head. It’s never going to happen. Never.”

Her eyes were welling up with tears. “Ty, don’t be so stubborn.”

The tears reminded him how careful he had to be about using the word never with Stacey. Somehow it always came back to bite him.

He’d said never the first time he’d seen her in makeup, reacting to how the inexpertly applied gunk had stolen the fresh innocence from her face. And then he’d ended up paying for her to take a full day of instructions in makeup application at Face Up and buying all the products she needed. That had been about a whopper of a bill.

He’d said never to her choice of a prom dress, low cut, clinging, way too old for her, and ended up being dragged into places no man in his right mind wanted to go, for days, finding a dress they could both agree on.

And he’d said never to the hippie, which had made the hippie twice as attractive to her, and made him realize that it was no longer his job to say anything to Stacey. Somehow, with so many stumbles on his part and so many mistakes, she had grown up, anyway. Into a young woman who knew her own mind and made pretty reasonable decisions most of the time.

But not this time. “What were you thinking, entering my picture without asking me? Geez, Stacey!”

“It was just a lark. Harriet suggested it.”

Somehow he should have known Harriet was involved in this disaster. Harriet and disaster went together as naturally as peanut butter and jam, saddles and cow horses, trucks and tires.

“Besides,” his sister said blithely, “how did I know you were going to win?”

He sighed. Was she deliberately missing the point? She was wiping tears off her face with the back of her sweater, getting little black smudges all over the white sleeve. Hard to stop noticing stuff like that even though he didn’t buy her clothes anymore.

“Could you take me for lunch?” she said with a little hiccup. “You must need a break from Cookie’s meals by now. Besides, you hardly ever see me anymore.”

He looked at her. His little sister was all grown up. Becoming more a big-city woman every time he saw her. Maybe it wasn’t such a good idea to pass by these chances to be with her.

“Okay,” he said grudgingly. “Lunch. But cheap and fast.” He was thinking along the lines of the Burger in a Bag he had passed on the corner before this office building.

Of course she took him to a little French restaurant that wasn’t cheap and wasn’t even remotely fast.

Despite his annoyance with her, she made him laugh when she told him about how she was hiding a Saint Bernard that she had found, in her little apartment. So far no one had answered the ad she had put in the paper.

“The dog,” she said proudly, “knows how to open the fridge.”

A Saint Bernard who knew how to open the fridge? “That explains why the owners aren’t answering the ad,” Ty commented.

The food came. He’d refused wine—wine with lunch?—but Stacey had ignored him and was pouring him another glass from the carafe of house white that she had ordered.

“You know, Ty, Mom died of breast cancer.”

He took a long sip of wine, then set it down. Okay. Now that Stacey had fed him and lured him into drinking wine with lunch, she was going to try and sucker punch him.

“I hadn’t forgotten,” he said quietly.

“Don’t you think it’s our obligation to fight the disease that took our mother? Don’t you remember how awful it was?”

He suspected he remembered better than she did, since he had been older at the time. He glared at her, seeing the corner she was backing him into. He said nothing and against his better judgment took another sip of the wine.

“That calendar could make the research foundation a lot of money.” She made sure she had his full attention, laid her hand on his. She named a figure.

He nearly spit out the wine. “Are you serious?”

“Dead serious. It’s not very many people who have a chance to give that kind of money to the charity of their choice.”

“Just because I said I don’t want to do it doesn’t mean they aren’t going to go ahead with the calendar.”

“No. But ninety percent of the women who voted liked you—ninety percent. That’s huge, Ty, especially if it translates into them buying calendars. There are 750,000 people in Calgary alone. I estimate 200,000 of them are women. If only fifty percent of them bought calendars, that would be a huge amount of money! In this city alone!”

He could feel his head starting to swim, and not from the wine. “Stacey,” he said carefully, enunciating every word, “I’m not doing it.”

He avoided saying never.

“Oh, Ty.” She sighed and looked at her fingernails. “You wouldn’t even have to come in to the city. You wouldn’t even have to miss an hour’s work.”

“I said no.”

“You wouldn’t even know the photographer was there. The photographer’s all lined up. World class.”

“No.”

“So, it won’t cost you anything, not even time, and you have a chance to contribute so much to a cause that is very meaningful to you, and you say no?”

“That’s right,” he said, and he hoped she didn’t hear the first little sliver of uncertainly in his voice.

“If the calendar was a huge success, I think I’d get a raise. I’d be able to buy a little house. With a backyard for Basil.”

“Basil is the Saint Bernard, I hope.”

She nodded sadly. “I think the landlord suspects I have him.”

“I’m not posing for calendars so you can keep a dog that’s bigger than my horse and has the dubious talent of opening a fridge.” At least, he thought, his sister was planning her life around a dog, and not the hippie. He noticed she hadn’t mentioned the beau today. Did he dare hope he was out of the picture? Or was it because Ty had lost his temper when she had mentioned the hippie and marriage in the same breath once? He decided he didn’t want to know.

She took a little sip of her wine and looked at her lap. She finally said, in a small voice, “You know my chances of getting it are high, don’t you?”

“What?” There. She’d managed to completely lose him with her conversational acrobatics.

“My chances of getting breast cancer are higher than other peoples. Because Mom died of it.”

“Aw, Stacey.”

“The only thing that will change that is research.”

He looked across the table at her and saw her fear was real. He felt his heart break in two when he thought of her in terms of that disease. Wouldn’t he have done anything to make his mother well?

Wouldn’t he do anything to keep his little sister from having to go down that same road? From diagnosis to surgery to chemo to years of struggle to a death that was immeasurably painful and without dignity?

If he was able to raise those kinds of dollars to research a disease that might affect his sister, did he really have any choice at all? If the stupid calendar raised only half as much, or a third as much as his sister’s idealistic estimate, did he have any choice?

Wasn’t this almost the very same feeling he’d had the day a social worker had looked at him and said, “She could go to your uncle Milton. Or to a foster home close to here. If you can’t take her.”

He glared at his sister. He saw the little smile working around the edges of her lips and realized they both knew she had won.

“Don’t even think I’m taking off my shirt,” he said, conceding with ill grace.

“I don’t know, Ty. If you took off your shirt, we might be able to sell a million copies of the calendar.” She correctly interpreted the look he gave her. “Okay, okay,” she said, laughing. “Thank you, Ty. Thank you. I owe my life to you.”

He hoped that would never be true.

She got up out of her chair, came around the table, threw her arms around his neck and kissed him on his cheeks. About sixteen times.

Until everyone at the tables around them were looking over and smiling indulgently.

“This is my brother,” she announced, happily. “He’s my hero.”