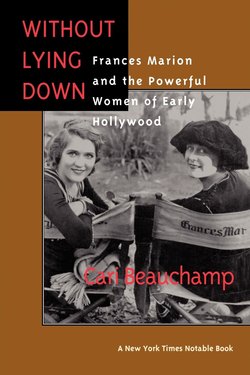

Читать книгу Without Lying Down - Cari Beauchamp - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPrologue

Wednesday evening, November 5, 1930, Fiesta Room of the Ambassador Hotel, Los Angeles, California

As Frances Marion rose to accept the Academy Award for Screenwriting for her original story The Big House, she became the first woman writer to win an Oscar. Since 1917, she had been the highest-paid screenwriter in Hollywood—male or female—and was hailed as “the all-time best script and story writer the motion picture world has ever produced.”

Just forty and “as beautiful as the stars she wrote for,” Frances was already credited with writing over one hundred produced films. Her importance to MGM was reflected by the fact that films she had written were nominated this evening in seven of the eight award categories—every one but Interior Decoration.

As she looked out from the podium at the six hundred people gathered at the Ambassador, she saw the faces of the friends she had literally grown up with in the business since first arriving in Los Angeles in 1912.

There was Mary Pickford, who called Frances “the pillar of my career,” for she had written Rebecca of Sunnybrook Farm, Pollyanna, A Little Princess, and a dozen more of Pickford’s greatest successes. Frances was also her best friend and had seen her through her divorce from Owen Moore and marriage to Douglas Fairbanks; Frances and Mary had even honeymooned with their new husbands together in Europe.

Irving Thalberg was the “boy genius of Hollywood,” but Frances called him “my rock of Gibraltar” and he was the only man in the room whose opinion she truly valued and respected. He in turn “adored her and trusted her completely.”

Greta Garbo still only spoke Swedish when Frances met her sitting on the sidelines of the set of The Scarlet Letter and tonight she was nominated for Best Actress in Anna Christie, adapted for the screen by Frances Marion.

Norma Shearer was now the “Queen of the lot,” but she was still fighting for roles when Frances first knew her, long before she married her boss Irving Thalberg. Tonight, Norma was nominated for Best Actress in Their Own Desire, adapted for the screen by Frances Marion.

Clarence Brown was nominated for Best Director for Anna Christie and had come a long way since being the assistant on The Poor Little Rich Girl in 1917 when he witnessed the “spontaneous combustion” created by Frances and Mary Pickford as they worked together.

Marie Dressler had been a top vaudeville star when Frances was a cub reporter interviewing her in 1911, but Marie’s career was over and she was facing dire poverty fifteen years later when Frances wrote the films that brought her to Hollywood to become MGM’s top moneymaker. The next year she would win the Best Actress award for the role Frances wrote for her in Min and Bill.

Gloria Swanson was one of Hollywood’s most glamourous stars; she was married to a count and spent a fortune on maintaining her fabulous wardrobe. Tonight, Gloria was only weeks away from learning that she too had been duped by a treacherous Joseph P. Kennedy, just as Frances had been two years earlier.

Hobart Bosworth was the éminence grise of the industry, having acted in over three hundred films, but in 1914 he owned the studio where Frances was first hired as an actress and assistant to the director Lois Weber at fifteen dollars a week.

Conrad Nagel was tonight’s master of ceremonies and a popular star, but Frances had first seen him as a young man rehearsing on the Broadway stage in 1915. She had sat alone in the theater that day with the impresario William Brady, who hired her on the spot to write for his World studio in Fort Lee, New Jersey, where she spent over a year honing her skills.

Sam Goldwyn had been the first to raise her salary to $3,000 a week in 1925 after she wrote some of his biggest hits, including Stella Dallas and The Winning of Barbara Worth.

Louis B. Mayer was now her boss at MGM, the largest and most successful studio in Hollywood, but he had pinched Frances’s rear end the first time he hired her to write a script at his then small studio only seven years earlier.

George Cukor was still a young emerging talent at RKO, but they were to become lifelong friends after making Dinner at Eight and Camille together. Cukor called Frances a “Holy Wonder—so ravishingly beautiful and so talented.”

And there was Adela Rogers St. Johns, her friend since their girlhood in San Francisco. Adela would also be nominated for Best Original Story in 1932, but lose to Frances when she won her second Oscar for The Champ. Yet Adela harbored no jealousy of the woman she claimed was “touched with genius. As a writer, she is the unquestioned head of her profession. . . . As a woman, she is a philanthropist, a patroness of young artists, and herself the most brilliant, versatile and accomplished person in Hollywood.”

Few knew or loved the industry as Frances did, yet after she said her demure “Thank you very much” and returned to her seat, she studied the statuette and decided, “I saw it as a perfect symbol of the picture business: a powerful athletic body clutching a gleaming sword, but with half of his head, the part which held his brains, completely sliced off.”

Privately, she was proud of her Oscar for The Big House because she had conquered a variety of obstacles to create a realistic film where for the first time audiences heard prison doors slam shut, inmates’ steps shuffle down the corridors, and metal cups bang on the mess tables.

Writing of that night, several historians called Frances Marion “the author of The Big House and just about everything else at MGM” but she called herself “a mouse at the feast” that was Hollywood. She habitually used self-deprecating humor as her armor against the professional and personal challenges and tragedies she faced.

Eventually Frances was credited with writing 325 scripts covering every conceivable genre. She also directed and produced half a dozen films, was the first Allied woman to cross the Rhine in World War I, and served as the vice president and only woman on the first board of directors of the Screen Writers Guild. She painted, sculpted, spoke several languages fluently, and played “concert caliber” piano. Yet she claimed writing was “the refuge of the shy” and she shunned publicity; she was uncomfortable as a heroine, but she refused to be a victim.

She would have four husbands and dozens of lovers and tell her best friends she spent her life “searching for a man to look up to without lying down.” She claimed the two sons she raised on her own were “my proudest accomplishment”—they came first and then “it’s a photofinish between your work and your friends.”

Her friendships were as legendary as her stories and some of the best were with her fellow writers for during the teens, 1920s, and early 1930s, almost one quarter of the screenwriters in Hollywood were women. Half of all the films copyrighted between 1911 and 1925 were written by women.

While Photoplay mused that “Strangely enough, women outrank men as continuity writers,” it wasn’t strange to them. Women had always found sanctuary in writing; it was accomplished in private and provided a creative vent when little was expected or accepted of a woman other than to be a good wife and mother. For Frances and her friends, a virtue was derived from oppression; with so little expected of them, they were free to accomplish much.

They were drawn to a business that, for a time, not only allowed, but welcomed women. And Cleo Madison, Gene Gauntier, Lois Weber, Ruth Ann Baldwin, Dorothy Arzner, Margaret Booth, Blanche Sewall, Anne Bauchens, and hundreds of other women flocked to Hollywood, where they could flourish, not just as actresses or writers, but also as directors, producers, and editors. With few taking moviemaking seriously as a business, the doors were wide open to women.

Frances maintained they took care of each other and claimed “I owe my greatest success to women. Contrary to the assertion that women do all in their power to hinder one another’s progress, I have found that it has always been one of my own sex who has given me a helping hand when I needed it.”

Today, names of screenwriters like Zoe Akins, Jeanie Macpherson, Beulah Marie Dix, Lenore Coffee, Anita Loos, June Mathis, Bess Meredyth, Jane Murfin, Adela Rogers St. Johns, Sonya Levien, and Salka Viertel are too often found only in the footnotes of Hollywood histories. But seventy years ago, they were highly paid, powerful players at the studios that churned out films at the rate of one a week. And for over twenty-five years, no writer was more sought after than Frances Marion; with her versatile pen and a caustic wit, she was a leading participant and witness to one of the most creative eras for women in American history.

This is her story.