Читать книгу Strange Way to Live - Carl Dixon - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

follow the highway ’til you hit the ocean, then keep going

ОглавлениеA tour of Newfoundland in the spring of ’79 proved to be the Waterloo for the band with the stupid name Alvin Shoes. Somehow, at the end of our knucklehead’s tour of northern Ontario, we’d come out feeling pretty good about ourselves, thinking we were now battle-hardened veterans. We were full-time touring musicians, and everyone in the band had quit jobs or school courses to do it. Then Dan the agent set up six weeks of spring gigs in Newfoundland. Ominously, he warned us that this, the Eastern circuit, was the real “trial by fire” of new bands. Dan had no idea….

It seemed simple enough. We were to pack our cube van with instruments, amps, PA system, and lights and drive from Barrie to North Sydney, Nova Scotia, where we would board the Newfoundland ferry. On the other side at Port aux Basques we’d resume driving, crossing the entire length of Newfoundland to begin our tour at the Atlantic Place Strand bar in downtown St. John’s. We had a vague understanding of the task before us but did nothing special to research or prepare. We had a cash float of a few hundred dollars for fuel and ferry toll, and my mom loaned me my dad’s credit card for emergencies. How hard could this be? We had always just gotten in the van and started driving, and things had always turned out okay. Figure it out as you go: that was the plan.

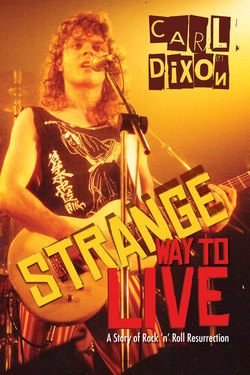

Alvin Shoes 1979 in full regalia. Left to right: Hal Hake, Chris Bastein, me a.k.a. “the girl,” and Blair Duhanuk.

Photo: Carl Dixon

Well, the trip began badly and went downhill from there. It’s actually kind of a big deal to make a journey of 3,150 kilometres, but you wouldn’t have known it by watching Alvin Shoes in action. Hal and Blair had once driven straight through to Fort Lauderdale, Florida, for spring break, so that was our yardstick. I’d never driven even half the distance we faced. It seemed to us in our collective wisdom that if we left on Friday night and then drove straight through, we’d make the ferry to Port aux Basques by Sunday. Landfall on the Newfie side would put us in position to drive the eight hundred and fifty kilometres across the island and set up to play our first night Tuesday. There was no margin for error needed because what could go wrong?

This is the story of what could go wrong.

We were three hours late for the scheduled departure while we worked at prying Brad, our soundman, out of the Queen’s Hotel disco and the company of a young lady he’d fallen for that same night. So compelling were her charms that he changed his mind on the spot about going to Newfoundland. Somehow we eventually found the right combination of persuasion and threats to get Brad into the van.

Once under way, we discovered after driving only fifty of the initial two-thousand-kilometre run to the ferry dock that we had an oil leak. This now required us to stop every hour, then half hour, to add another bottle of oil.

We hit Montreal around midnight in a rainstorm, now five hours behind schedule. The highway interchanges on the Décarie Expressway in downtown Montreal can be confusing at the best of times; Blair at the wheel and me navigating somehow put us on the southerly route toward Sherbrooke, a wrong turn that took us two hundred kilometres out of our way.

Our ship of fools pressed on, stopping every so often to pour in fresh oil from the stash we now carried, but every service station on our secondary highway route through rural Quebec was closed for the night. Running on fumes in the pre-dawn hours heightened our choking anxiety. I was sustaining a hope that we could still make it on time for our first night in St. John’s, in spite of our errors, if we could just nurse the cube van along somehow. Running out of gas, though, now? How idiotic would that make us?

The possibility of missing our gig was unacceptable, inconceivable, and I shifted into marshalling all my thought, resourcefulness, and courage to forestall that unhappy outcome. I was going to get us there, period.

We reached a small town in Eastern Quebec at about 3 a.m. There was an old-fashioned service station, one where the owner lived upstairs. This was our chance to keep alive the spark of hope that we might still reach the ferry on schedule, if we could just get fuel and keep moving. If we parked until morning we’d miss the boat, literally.

For some reason I believed that gas station operators held a sacred trust to aid travellers in distress. Armed only with a smattering of grade seven French, I decided to address the house. Dim memories of “La Famille Leduc” (“Peitou manger le rôti d’bœuf,” etc.) led me to holler up at the apartment, “Ah-Sée-Stawnse! Ah-Sée-Stawnse, Sill-Voo-Play!” My urgency was not felt by the people who lived upstairs, and I tried repeatedly to make my meaning clear. There may have been a language barrier. In any event, the only sign of life was a slight flutter of the curtain; otherwise all remained dark and quiet.

I think it’s fair to say that a kind of craziness took me over at this point. I was bitterly frustrated. I left the guys to wait with the van at the service station while I went to scout around. In full confidence that I was being clever and resourceful in a crisis, I started darting around the lawns and driveways of the sleeping town, prowling through people’s back yards in the hope that someone’s full gas can might have been left out for me to “borrow.” No luck.

I was roused from this little fantasy by a mustachioed Quebecker in a muscle car, out cruising at 3:30 a.m. for some reason. He spotted me emerging from someone’s yard just as he drove by, so he applied the brakes and swiftly began to turn around. Instinct told me to run. I cut back through the yard where I’d just been, over the fence, and through the next neighbour’s yard to the street beyond. My souped-up pursuer was speeding around the corners to try to intercept me, tires squealing. I sprinted across the open street and through another two back yards. The driver probably imagined being feted as a local hero for catching a “maudit anglais” in the act of doing suspicious stuff. I recognized that I would have a hard time explaining my decisions to the law, so I went into full evasive action. Cut hard right for two back yards, jumping fences, then double back to the spot where I began running. Flat on the ground behind someone’s garbage cans, I lay very still as I heard the car speed around the streets close by for maybe another five or ten minutes. Monsieur Muscle Car gave up after a time, and the sound of his engine faded.

A different approach seemed prudent. Getting fuel somewhere was still the only thought I could hold. We must get to the gig! As I cautiously walked back to the service station, I noticed a Quebec Provincial Police outpost a block or two from the highway. Great! They’ll help us get fuel. The doors were locked but there was a call box. I picked up the receiver; it quickly auto-dialled and was answered by someone whose main language was, of course, French.

In time I was able to make him understand why I was calling, and he told me that my location was a satellite station, only open in the daytime. He was speaking to me from the nearest station, half an hour away. I thanked him, hung up, and started to think about this new information. I thought about the QPP car sitting parked and untended until morning in this little town, about how all the cops on duty were in that town half an hour away and, God help me, about how that police car was bound to have fuel in the tank.

I hurried back to the service station where the guys remained waiting. “Okay, does anyone know how to siphon gas?”

They say craziness is contagious, and I guess we were all so tired and stressed that I was able to overcome the good sense of my fellows and convince them that this could work. It seemed awfully clever in the moment.

It was agreed that you need a hose to siphon gas out of a car. Then you have to get past the awful taste of the gasoline. Who volunteers? Ha-ha. Now let’s find a hose. I’d seen some in the yards where I’d been skulking, but I didn’t want to go back down there. Hey, there’s an air hose on the tire pump of the service station. Scoop.

Now, off to the police station and the lonely car in the lot. We pulled the van up at an angle so our gas tank was near the police car’s. Their gas cap was standard issue, no locking device. Stuff one end of the hose down into the QPP gas tank and have our tank open at the ready. This’ll be great! Chris had a try at sucking hard on the hose, to no effect. I fancied that I had extra lungpower, so I tried. Nothing. Someone pointed out that the hose was at least twenty feet long and had a very narrow opening, as befits an air pump hose. It would be impossible for even Hercules to siphon gas through that. Man, we were the world’s worst criminals.

We began frantically searching now for something to shorten the hose, but what to use? Hey, here’s a pop bottle. Break the glass and use the jagged edge to cut! I smashed the Coke bottle to reveal the thick glass of any standard issue Coke bottle, sans jagged edge, but tried sawing away anyway. The futility of this finally sapped my remaining belief in the idea. In disgust I lifted my head, blew out the pent-up air in my lungs, and took a step toward the street. At the same moment a QPP cruiser roared up the street right past us.

There were two officers in the front seat, one at the wheel and the other holding a shotgun upright ready for action, but neither one looked to their right, where we were standing. They likely never expected to have a crime scene unfolding right in the police station parking lot. I barked, “Back up the van away from the car! Close the gas tank!” It was now critical to hide the evidence. In early April in Quebec there were still high snowbanks, so I grabbed the air hose and the broken pop bottle pieces and heaved them over the snow banks, where they’d be hidden. Just as I completed this task, the police pulled up abruptly on the sidewalk to face us with the patrol car and block our exit.

They got out of the car with shotgun still at the ready and demanded to know what we were doing. I turned on the innocent-kid-from-small-town-Ontario charm and glossed over the unpleasant parts of the story. I explained our predicament: that we had a long trip ahead and we were almost out of fuel, and said we had come to the police station hoping to get help but found it closed. That much was true, just a few gaps in the tale.

The police relaxed a little, and I think they even liked that we were a band. One checked with the call centre to verify that, yes, someone had called from the outpost call box asking for help maybe an hour ago. The two officers told us they were in town responding to a local complaint that there were strangers in town doing some funny stuff, but they felt sure now that our actions had been misinterpreted.

Unbelievably, they now took it upon themselves to help us get on our way. There was a Shell station maybe ten miles up the highway. They called the owner and asked him to get out of bed to come and pump gas for these poor musicians. They even gave us a police escort. They were such nice guys that I felt bad about fooling them. However, the pulse of our mission was still beating, faintly. That was all I cared about that night.

We now had a full tank to resume a run for the ferry dock, but there remained the oil leak problem. None of us was a mechanic but we could hear well enough that our engine was going da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da-da, louder each hour. We were stopping every fifteen or twenty minutes now, and that wasn’t good. The engine was overheating over and over, but we had no idea what to do except drive on grimly and see how far the doomed vessel would carry our weary crew.

Just about the time I was beginning to see double from being up all night, a ferocious pounding din broke out as if someone had crawled in under the hood to wield a ball-peen hammer. There was shouting and steam and fumes and hissing as we pulled off to the shoulder and then … silence.

Within a few miles of the New Brunswick border, but still only halfway to the ferry, we had created an immovable object. That cube van was dead.

I know it will seem like I’m always at the centre of the story, but I think I just clamoured to be there because it always seemed as though that was where I should be. In this case I decided that we had to find help to continue our quest. I believe I still hadn’t quite surrendered. Somehow, I got a tow truck involved to pull the van into the next town, a little place called Dégelis. We were exhausted. We got the local mechanic to look it over. His diagnosis was swift: blown gaskets had led to oil leaks, which led to overheating, which led to the pistons seizing and the engine block warping when we kept driving. A rebuilt engine would have to be dropped in, to the tune of four hundred dollars. Was that a good price? We had no idea. It had to be done, though. We couldn’t stop there, and we weren’t going home. Good thing I had my dad’s credit card.

We had to cool our heels for a day or two in a little motel at Dégelis and spent most of our pocket cash. Poor Brad tried killing time by kicking a soccer ball around with Curly in the parking lot, but he gave the ball such a hoof that it flew up and smashed a hole in the motel’s neon sign. Brad had to cough up a hundred and fifty dollars to pay the bill and was now just as broke as us.

With all this aggravation before we’d even played a note, you might expect that the story would now settle down, that the band would figure it out and get in a routine once things got going a bit. In fact, the start was only a harbinger of one unlikely event after another.

Obviously, the goal of arriving on time for the first week in Newfoundland was not achieved. We did get our new engine and the van running well in pretty short order. Meanwhile, our agent, Dan, contacted the Kirby Agency in Halifax to ask them to help find us something on an emergency basis; he’d been able to salvage our second week of two in St. John’s. They got us a weekend gig at the Red Lion Pub in Dartmouth, which seemed a bit rough to me, but the Red Lion was willing to let us play and pay us for it. We were directed to the Inglis Street Lodge in Halifax as a place where musicians often stayed while visiting that city, so we paid for rooms there and in fact did meet some of the East Coast bands going through the place.

Unfortunately, all was not uneventful. I’ll quote from a letter I wrote home from Newfoundland when the memory was fresh. It went like this:

… The night I spoke to you on the phone from Halifax an arsonist struck at our lodgings at about 3 in the morning. The story is that a long-time tenant had a falling-out with the owners and decided to have his revenge. Brad, Blair, and I were sharing a 2nd floor room while Chris and Hal were in the basement. The fire was set in two places: just outside our door where some highly flammable curtains were hung, and in the bathroom which opened onto the only stairs. I awoke to a muffled commotion of human voices and an odd hissing sound. I sprang from my bed to see what was the matter.

The hall, when I peered out the door, had a strange white light in it. I then realized that it was smoke-filled, which muffled the voices. The hissing sound was the automatic sprinkler spraying down. I turned and yelled at the others and we skedaddled out. Luckily I had slept in my grey track pants, but Blair and Brad were in their underwear and it was a very cold night. We were all barefoot and shirtless, wondering where the fire department was.

Blair ran back inside to get his leather football-team jacket at possible risk to life and limb because he refused to stand out there freezing any longer in just his underwear. He returned swiftly wearing the coat. After a minute I looked over to where our van was parked and saw a girl trying to climb out a window about seven feet above it. She felt trapped by the fire but was afraid to jump, so I scrambled onto the top of the cube-back and helped her and a guy friend get down. The fire department showed up in a couple of minutes and they found that the only real damage was smoke and water damage….

Before we could leave the Red Lion, our music store demanded the return of our rental lights to Ontario. We left them behind in the bar for the Halifax agent to ship back for us on Monday. Agents don’t like those jobs.

We drove up Cape Breton in fine sunny weather to North Sydney to catch the night ferry — a week late but, by gar, we were getting there! We’d never been to sea, so the crossing was exciting. Hal and Blair got a berth and took turns sleeping in there.

At about 6 a.m. our vessel emerged from the fog to our first sighting of “The Rock,” at Port aux Basques. On one hand I felt an exciting kinship with the first Europeans who landed there centuries before. On the other hand it looked to me like we were approaching the end of the earth. Was this a hint of foreboding?

The Alvin Shoes band disembarked and started driving across the entire island to St. John’s to begin our delayed conquest of the Rock. Hoorah! Only, as it turned out, the Rock conquered us — or more accurately, we defeated us.

We got into the Atlantic Place Strand, right downtown, for set-up and began the week’s run. Our lack of lights was embarrassing, and the musical performance was leaden and amateurish. Everyone had been traumatized by the journey to get there, and we had no idea that we were supposed to be this “hot new band” from Toronto.

I thought we were doing “better” after the first night, but our dispirited show was still bad enough to provoke an outraged article in the local newspaper’s entertainment guide the next week, in which the reviewer asked the priceless question, “Does the mainland think they can send us any old crap like this Alvin Shoes band and we’ll just take it?”

On the Thursday night everyone in the band came to me to tell me they were quitting, only agreeing to finish up our existing booked commitments till summer so we could pay my mom back more of the cube van purchase price. I felt very guilty about the band collapsing after convincing my mom to help us out financially.

As I wrote to her:

I guess I should tell you the main thing which motivated this letter. Last night things fell apart and everybody (me included, but last) announced their intentions of quitting when this tour is over.

Anyway, you’re now up to the minute. I had better get to bed soon or that will make three nights in a row I’ve watched the sun come up.

Love to everyone, Carl

P.S. Not to worry.

“Not to worry.” Right. Mothers don’t worry much.

That was Good Friday and we had the night off because of the religious holiday, so we all went out and got drunk and smoked cigars. It was actually fun to blow off steam. Out on the town I must have cut quite a wasted figure, but a petite young lady in her mid-twenties with long blond hair showed a keen interest in me even so. She suggested that we could go somewhere, and somehow a room was rented. When we got there she removed her very high heels, and even to my double vision it was obvious she was in fact not only petite but tiny, like maybe four foot eight. Probably something ensued. I don’t remember. In the morning she was gone and my pockets were empty. She must’ve needed the cash more than I did.

Next day most Alvins straggled into the Atlantic Place around dinnertime in search of food, badly hung over and with “the big quit” fresh on our minds. That’s when we discovered that we were supposed to have played two matinee shows that afternoon. We had now made our disgrace complete by failing to appear for this time-honoured Saturday afternoon whoop-up. A long night followed as we wore our failure. Please let this end, we prayed, so we can get on to the next town and start fresh.

Harbour Grace and its Pirate’s Cave club was next. Mercifully, it was a fairly short drive on Sunday, just an hour or so. We pulled up to the building and the owner, Sam, a great big fella, and his bartender came out to greet us with broad smiles and friendly handshakes. Nice welcome. Then they peered past us into the van and said, “So, where’s the girl?”

We soon realized that when the Alvin Shoes promo photo had arrived from Pizzazz, they’d mistaken me for a girl singer. Hoo, boy! Must have been the hat. Their disappointment was plain as we left them to go claim our rooms in the band house.

We had the night off, so we wondered what to do. There was a public swimming pool in Carbonear, a town about ten miles away, so we decided it would be fun to go make a splash and change up the mood. After some paddling about and silliness in the water, I thought it would be goofy and fun to have a dog paddle race, and everyone greeted this idea with enthusiasm. A harmless bit of play, you’d think, and so it was until I reached the end of the pool, about to win, and reached up with my left arm to touch. Trouble was that I’d dislocated that shoulder twice in the previous year and the joint now slipped off the bone again from the water resistance. I yelled in pain as I started to sink in the deep end, and the lifeguard came running to pull me up by my good arm. Off to the hospital now, me still in bathing suit, where they were not super quick in the emerg ward. With that particular injury, shoulder dislocation (I’ve had seven of them over the years), the area is numbed a bit at first by the shock, but after half an hour or so it begins to go into excruciating spasms as the joint demands to be restored to its proper position. By about an hour after the injury, I was failing to suppress a few gasps and moans in the waiting room, and a nurse came out to scold me in stern Newfoundland tones.

“You just be quiet now with all your noise, there’s pee-pull in here who’s really hurt! Hush!”

Eventually a doctor twisted my shoulder back on and applied a body brace to immobilize the arm. Well, that was just great. How would I play guitar now?

“The singer’s got a broken neck!” Big Sam the club owner complained as he called the agent to fire us. It was bad enough the singer wasn’t a girl; now I was sporting a sling from a major injury and awkwardly playing rough guitar with my arm immobilized.

Next day we woke up fired. I’d never been fired before. I was called in to the Pirate’s Cave office to receive the news and learn how little we were going to receive of our pay. A one-eighth portion was all we’d get because weeknights are worth less than the weekend. Also, we had to move out of the band house, now. A band called the Rhythm Method who had the week off happened to have turned up looking for somewhere to stay, and they’d now take over our week. I got mad and frustrated and was ready to physically contest Big Sam, even with my dislocated shoulder, for a greater portion of our reduced fee until he warned me that he used to be a pro wrestler and I should just drive off now, like a good lad. I took his meaning. I actually shook hands with Sam as we left. It was nice of him to give me the warning instead of just flinging me about.

Well, we had to stay somewhere, so we moved on to Corner Brook, and I rented us some rooms with the credit card. We just had to hang on until the next week at Grand Falls-Windsor and Stephenville after that, tightening our belts for a few days, and we’d still get some cash to take home.

I got my own room and the others doubled up because we were now on opposite sides of the who-quit-who divide. How excited I was to get a slip of paper from the front desk of the Corner Brook hotel saying I had a telegram. Wow, receiving my first-ever telegram, like a scene from an old-time movie! What could it be?

I went to the office to claim it. It was an official notice that we were fired from our tour-ending week in Stephenville because of “false advertising.” They’d read the reviews from St. John’s and monitored our faltering progress. Hit me again, bartender. Wow, fired twice now.

There was a nice lady in Grand Falls who owned the club we were booked into next, the Loggers Lounge. She permitted us to come in a day early to take up rooms at the Cloverleaf Motel, where all the bands stayed. That night we went in to watch the band that was finishing up its week. Cool name on them too — Firefly — from Montreal; strong presentation, good singing, good playing. I acutely felt the contrast between us and them, and I wanted to feel like them, not us.

Our turn now at the Loggers, and over the following nights it was a forlorn bunch of Alvins who were releasing flatulent performances to the patrons who stuck with us. The feeling of surrender was following us like a bad smell as we played out the string. I didn’t know yet how to summon up the good stuff when I needed it.

We finished up on the weekend, got the money (which was enough to get us home, at least), and moved on. We stopped at the Lorelei Lounge in Stephenville to see Steve Butler, the guy who had fired us by telegram. I don’t know what I thought would happen. Maybe he’d relent and give us a week if we were there anyway? He gave us all a shot of whisky in mid-afternoon, the civil thing to do, and sent us on our way. We got to the ferry boarding dock back at Port aux Basques, where the bands Firefly and Rhythm Method unexpectedly would share the crossing with us after completing their own tours. I befriended people in both bands, presciently getting names and phone numbers. The next contact with Firefly lay just around the corner; playing with Mark Severn from Rhythm Method lay many years in the future.

All that was left was to drive all the way back to Barrie with no stops. All the guys grew happier as we neared home. Still sporting my shoulder brace but back to lifting dumbbells to build strength as we motored along, I was convinced I had to be hard to get through this change. Over the following two months Alvin Shoes would play out the string of remaining shows around Ontario before grinding to a halt.

The story seems unbelievable when you take it in whole. If luck is the moment where preparation meets opportunity, this misadventure was the precise opposite. We didn’t know how naive and unprepared we were, even when it was over. For my part, I didn’t understand how badly we’d done until I learned how to do it better.

Four of the five people who experienced all this took it as a sign from the gods to go home and return to regular jobs or school and a quieter, more sensible life. One of the five took it as a sign to search for his next band.