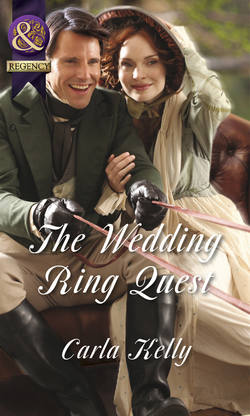

Читать книгу The Wedding Ring Quest - Carla Kelly - Страница 8

ОглавлениеChapter One

This was no ordinary return to Plymouth; Captain Ross Rennie felt it in his bones. A frigate captain much wiser than he—dead now, like so many friends—had described it best during one of those chats on the far side of the world when another frigate pulled alongside to visit and hand off mail.

In the course of their conversation over beef too long in brine and green water, they described recent fights with the French or Spanish, depending on where national allegiance had swung in an endless war. The long-defunct captain had looked Ross square in the eye and said, ‘Sometimes a victory is only a hair’s breadth better than a defeat.’

A young captain at the time, Ross had nodded, wondering later what the devil the man meant. As his thirty-six-gun frigate Abukir sailed into Plymouth on a rainy day, Ross felt that hollow, sinking feeling of defeat, when he should have been over the moon with joy. The emotion had been growing since his ship had been ordered to join the convoy escorting Napoleon and his entourage to Elba after his banishment there in 1814 by the Allies. A time or two during the short voyage from France, he had stood on his own quarterdeck and observed Bonaparte on HMS Undaunted, Captain Tom Ussher’s frigate.

Ross almost hated himself for finding the man so fascinating, but the exiled emperor seemed to demand attention. Ross noticed other telescopes trained on Napoleon.

The longer he watched Napoleon, the greater grew his personal sense of disquiet, the greater his sense of defeat. Normally a sanguine fellow, Ross felt himself grow grim about the mouth. He’s so short and stout, Ross thought. So ordinary. He took his observation into dangerous territory then, the worst place any officer could take himself. How in the world did this man rule my life for twenty-four years? Ross found himself asking.

For he had. For more than a generation, Ross had sailed where this tyrant intended, fought French and Spanish ships, logged miserable hours twice in prisons, lost a leg, found a true love and lost her, too. Supposedly he was in the service of poor King George III, but Ross knew what all officers and men in the Royal Navy knew—had there been no Napoleon, there would have been no war. He would probably never have gone to sea in a fighting ship. Without that stout little man, Ross Rennie would probably have conned nothing more dramatic than a merchant vessel.

‘You ruined my life,’ he murmured one lazy afternoon as they approached the island of Elba, some twelve mere kilometres from Tuscany. The only man within earshot was the helmsman and he was used to hearing his captain mutter.

But because he was sanguine and normally rational, Ross had to reason with himself. Was this true? The war was over, so he did something unheard of: he leaned his elbows on the ship’s rail. He looked up when he heard the sails luff, and laughed, knowing his sudden lapse of ship’s discipline had caused the helmsman to stare and lose his concentration.

Embarrassed, Ross straightened up and administered the patented Rennie stare to his helmsman, who quickly corrected his error. Not one to leave a good seaman flustered, Ross nodded to the man. ‘I’m going to do it again, Carter,’ he said and returned to his casual pose. The Abukir continued on course.

True to his nature, Ross made a mental list of pros and cons. Aye, he had spent his life on board fighting ships, but that had likely proved more interesting than coasting around England and Scotland, and maybe to far-off America with a cargo of dried herring, shoes or corsets.

Had the navy not taken him to exotic Portugal, he would never have met Inez Veimira, whose love still made him smile. And he most certainly would never have fathered the boy who waited for him now in Plymouth, a boy with hair as dark as his own, but curly, with full lips instead of Scottish ones and an olive tint to his skin. Nathan’s brown eyes were his mother’s alone. Their beauty had given Ross pause to miss Inez Veimira, until his natural optimism turned his regrets into those little blessings a healthy son furnished.

The loss of his leg at Trafalgar in 1805 had not been without a little good fortune, as Ross chose to see it. The ship’s surgeon had only needed to take his mangled leg off five inches below the knee. Difficult as it was, and too long his stay in the Plymouth hospital, the surgeon had assured Ross that an officer who still had his knee could command a quarterdeck and expect advancement. And so it had proved.

And there was this, probably his greatest blessing: Napoleon’s stupid war had turned Ross Rennie into a leader of men, a rock-solid fellow whose sensible decisions made the Abukir a good home for men like him. The helmsman was a case in point. Once caught in Captain Rennie’s firm but benevolent web, men tended to stay there through the years, knowing they were in good hands.

Seen from this light, Ross decided perhaps the war that had spanned all seven seas and ushered out one century and welcomed another had not been a total failure. By the time the Undaunted and her escort dropped anchor in charming Elba’s harbour, Ross’s heart was calm again. True, the war was over with Napoleon and, as a valued post captain, Ross knew the Royal Navy would find something for him to do. As a father, he wanted to sail to Plymouth and spend some time with his son. It remained to be seen whether he had the clout to manage both, but he thought he did.

As it turned out, he was right on both counts. True, that immediate return to base in Plymouth had dragged out until November as the Abukir and others like her continued to patrol the Channel. While people in England had devoted much time rejoicing that the Beast was on Elba, the Royal Navy took a more cautious view and continued to patrol waters at least less hostile.

Hoys and lighters still made their way back and forth to victual ships like Ross’s long at sea and they conveyed letters. Many a night after mess Ross read and re-read his letters from Nathan and hoped his son did the same thing with the missives he sent, accompanied by those exotic things only a Navy man could come across: oranges and lemons, a prayer rug from North Africa and Gouda cheese from the Low Countries, specifically for Maudie Pritchert, who had the raising of his boy.

If only Ben Pritchert, sailing master, had lived to see Napoleon on Elba. On that final voyage from the Channel to Plymouth, he missed Ben even more than usual. It had been his sailing master, a father in his own right, who had suggested Ross take his infant son from Portugal to his own wife in Plymouth. In 1804, the year of Nathan’s birth, Oporto had suffered one of those earthquakes the coast was prone to. It was nothing as severe as the 1755 disaster, but the port merchant’s home had been demolished, along with all its inhabitants except a week-old baby covered by his mother’s body.

So the nuns at the nearby convent had told Ross, as he had shouted Inez’s name over and over in the ruins, when he came into port a week after the quake. He knew she had borne him a child during his last voyage of seven months’ duration to the Baltic. More than that, he did not know. The unexpected voyage had scuttled elaborate wedding plans, beyond quick nuptials, because their child was already underway. But that was the Royal Navy, which took no interest in the lives of its men. The good sisters had taken over the care of his little morsel and laid his son in his arms when tears still streamed down his face.

They had willingly fostered his child, named Nathan Thomas Fergusson Rennie and christened in the Holy Catholic faith because that was what the nuns did. Three months later when HMS Fearless was posted from Oporto to Plymouth for extensive repair, the nuns had returned Nathan to him, along with a goat.

He had known there would be a seaman or two who probably knew exactly what to do with a milking goat and they had not failed him. What had touched him to his soul was the way every man on board took an interest in his son. There had been no lack of volunteers willing to walk back and forth with a colicky baby, after Ross was ready to drop from exhaustion. His son’s first English lullabies were sea ditties better left shipboard.

Maudie Pritchert had received the baby with open arms. Two years later, she wore widow’s weeds. It was no wonder that as his prize money collected ashore, Ross had purchased a better house for the Widow Pritchert and her four children, plus his son. He paid her a handsome income to raise the boy he only saw at intervals. Now that the war was over and he was sailing home, Ross knew he would continue that stipend throughout that kind woman’s career on earth, for she had saved his son’s life.

His debt was far greater. After Ross had learned to stump around on a peg-leg and manage a quarterdeck again, Ben Pritchert saved his life during a skirmish not even worthy of inclusion in the Naval Chronicle. They had been coasting off France when a larger French frigate came out to play. In the middle of hot action, Ross lost his balance on his rolling deck. His sailing master rushed to steady him and took the deadly splinter in the back that would have cut Ross in two. He would owe both Pritcherts until he died.

* * *

Sailing into Plymouth harbour this time was more bittersweet than he would have imagined. For nostalgia’s sake, Ross conned the Abukir, savouring the moment. He glanced towards the houses that marched up the gentle slopes away from the town centre, wondering if Nathan was watching. During his last visit a year ago, he had given his son a telescope. Maybe in a few years, he would give him a sextant. Maudie said the lad had an aptitude for mathematics.

On the advice of the overworked harbour master—so many ships returning—he dropped anchor, then looked around at the disorderly order on the Abukir’s decks. His orders said the ship was to be refitted and refurbished. Two months and he would sail again—where, he had no idea. Two months of shore leave was one month and three weeks longer than any break he had enjoyed since the Peace of Amiens in 1802.

With a reluctance that surprised him, Ross turned the ship over to his number one, assuring him he would return in a day or two to settle out any complications with dry docks. He knew his officers yearned to leave the Abukir as much as he did. The men would go home, too, those who had homes. Others would hang around the docks, spend their money and be glad to see him in two months, if they hadn’t been pressed into another vessel short of crew.

His chief bosun’s mate insisted on piping him over the side himself, which was flattery, indeed. Because all eyes on deck were on him, Ross did his best to descend the ropes with dignity, never easy with a leg and a half. When he was safely settled in his launch for the pull to shore, he raised his hat and saluted his crew. It’s only two months, he reminded himself as he felt unfamiliar tears gather behind his eyelids.

Although there were hackneys waiting to take him anywhere in Plymouth, Ross waved them off. He wanted to walk from the harbour to Maudie Pritchert’s house. He knew his sorely tried leg would start to ache before he got there, but he needed the opportunity to shake off his sea legs. In parts of England far from the coast, the watch would probably be summoned to deal with men lurching and rolling down the street. Not Plymouth, a Navy town that understood what it meant for its men to remind themselves how to walk on a flat surface that didn’t pitch and yaw.

A peg-leg presented its own challenges, but he arrived in good time at the base of Flora Street, with its pretty pastel houses. As always, he stood there a long moment, wondering how much his boy had changed. Nathan was ten years old now. No one knew what his actual birth date was, because there hadn’t been time to register anything before the earth moved in Oporto. A few visits back, the two of them had picked June 7th, an unexpected compliment, because that was Ross’s birthday.

When he had asked his son why he wanted to share a birthday, Nathan’s answer confirmed for all time that while it was possible to take a Scot far from the land of his ancestors, the economy remained. ‘Simple, Da,’ his son had told him. ‘It’s a tidy thing to do. We’ll have cake but once a year, but we’ll have twice as much.’

It was the perfect answer. Nathan, whose mother had been a heavy-lidded, sloe-eyed daughter of Portugal and deeply fond of cake, was a fitting combination of Dumfries and Oporto.

‘Twice as much,’ Ross agreed.

With the war over, he had plans this time, since a prodigal amount of leave stretched ahead that would take them through Christmas. The two of them were bound for Dumfries, where Ross’s older sister lived with her surgeon husband. He hadn’t seen her in years, but that was nothing because he had always been a prodigious correspondent and so was Alice Mae Gordon. She had promised them a good visit and hinted that she knew of a piece of property in need of a landlord in nearby Kirkbean. ‘In sight of open water,’ Alice had written, to further entice him.

He stood a moment more, wondering at the half dread he always felt, hoping his son hadn’t changed too much since the last visit, but well aware that children grow. Will he remember me? he always asked himself. If he passed me on the street, would I know him?

Ross took the customary deep breath and continued up Flora Street, his eyes on a yellow house, where flowers still fought the good fight against late autumn. He knew that in Scotland, the flowers had long surrendered to winter, but this was lovely Devon.

He walked slower because his leg pained him and because there was always that moment when he wondered who would greet him. For the first time since Inez’s death, for the first time in the terrifying and fraught years since, he wanted a wife to greet him, too. It was a heady thought and he entertained it cautiously, thinking of all the times he had assured his officers and wardroom confidants that he would find another wife when the war ended. Maybe the time was now.

Ross stopped outside Number Six Flora Street and looked up at the second-storey window that he knew was Nathan’s room. His heart skipped a little beat as his dear son looked down on him. The boy disappeared from the window and Ross watched the front door. It slammed open and his son hurtled outside and into his open arms.

Ross was home from the sea.