Читать книгу Texas - Carmen Boullosa - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеPART ONE

(which begins in Bruneville, Texas, on the northern bank of the Río Bravo, one day in July of ’59)

IT’S HIGH NOON IN BRUNEVILLE. Not a cloud in the sky. The sun beats down, piercing the veil of shimmering dust. Eyes droop from the heat. In the Market Square, in front of Café Ronsard, Sheriff Shears spits five words at Don Nepomuceno:

“Shut up, you dirty greaser.”

He says the words in English.

At that moment, Frank is crossing the plaza, muttering to himself, “…and make it snappy, make it snappy,” in English, which he speaks so well that people have changed his name from Pancho Lopez to Frank. He’s just delivered two pounds of meat and one of bones (for stewing) to the home of Stealman, the lawyer. Frank is one of the many Mexicans in the streets of Bruneville who run errands and spread gossip, a “run-speak-go-tell,” a pelado. He hears the insult, raises his eyes, sees the scene, leaps the last few feet to the market, and runs to Sharp, the butcher, to whom he blurts out the burning phrase at point-blank range: “The new sheriff said, ‘Shut up you dirty greaser!’ to Señor Nepomuceno!”, the syllables almost melting together, and continues immediately, in the same exhalation, to relay the message he’s been rehearsing since he left the Stealmans’ home, “Señora Luz says that Mrs. Lazy says to send some oxtail for the soup,” adding with his last bit of breath, “and make it snappy.”

Sharp, standing behind his butcher’s block, is so startled that he doesn’t respond by saying: “How could a puffed up carpenter dare speak that way to Don Nepomuceno, Doña Estefanía’s son, the grandson and great-grandson of the owners of more than a thousand acres, including those on which Bruneville sits?!” Nor does he take the opposing stance, “Nepomuceno, that no-good, goddamned, cattle-thieving, red-headed bandit, he can rot in hell for all I care!” These two perspectives will soon be widely debated. Rather, in his eagerness to spread the news, he (somewhat melodramatically) claps his left hand to his forehead and glides (dragging his long butcher knife, which scratches a jagged line on the earthen floor) two steps to the next stall, which he rents to the chicken dealer, and shouts, “Hey, Alitas!”, repeating in Spanish what Frank has just told him.

It’s been three weeks since Sharp has spoken to Alitas, supposedly they had a disagreement about the rent for the market stall, but everyone knows that what’s really pissed off Sharp is that Alitas has been trying to win his sister’s heart.

Alitas—happy to be on speaking terms again—enthusiastically joins in broadcasting the news, shouting, “Shears told Nepomuceno, ‘Shut up, you dirty greaser!’” The greengrocer, on hearing the news, repeats it to Frenchie at his seed stall, Frenchie passes it on to Cherem, the Maronite at the fabric stand, where Miss Lace, Judge Gold’s housekeeper, is examining a sample of material that’s recently arrived—a kind she hasn’t seen before but is perfect for the parlor curtains.

Sid Cherem translates the phrase back into English and explains to Miss Lace what has happened; she asks Cherem to save the cloth for her and hurries off to share the news with her employer, leaving behind Luis, the skinny kid who’s carrying her overloaded baskets. Luis, distracted from his duties by the rubber bands at a neighboring stand (one would be great for his slingshot), doesn’t even realize Miss Lace has gone.

Miss Lace scurries across the Market Square and half way down the next block, where she sees Judge Gold coming out of his office, heading to the Town Hall just across the street.

It’s important to explain that Judge Gold is not a judge, despite his name; he’s in the business of stuffing his wallet. His métier is money. Who knows how he got his name.

“Nepomuceno’s goose is cooked,” is what Judge Gold tells Miss Lace, because he’s just received another report, and with both bits of news in mind he continues on his way to the Town Hall, from which Sabas and Refugio, Nepomuceno’s half-brothers by Doña Estefanía’s previous husband, are exiting angrily.

Sabas and Refugio are proper gentlemen from the best of the best families of the region. Wagging tongues can’t understand how Doña Estefanía could produce these two jewels, and then the roughneck Nepomuceno, who doesn’t even know how to read. Others claim it’s a blatant lie that Nepumuceno is illiterate and consider him the most elegant and best-dressed of the three, with the manners of a prince.

Sabas and Refugio owe Judge Gold a lot of money. They’ve just been to testify before Judge White (who is a real judge, though not necessarily an honest one); the Mexicans in town call him “Whatshisname” instead of Judge. Nepomuceno preceded them but they waited until their messenger, Nat, told them that their half-brother had left so that they wouldn’t run into him. Nat was the one who reported to Judge Gold that the legal proceedings would be delayed “until further notice”—bad news for Sabas and Refugio, who want a ruling soon so they can get the payoff promised by Stealman. It’s even worse news for Nepomuceno.

A shot is heard. No one is particularly alarmed by the sound—for every 500 head of livestock you need 50 gunmen to guard them, and each of those gunmen will pass through Bruneville at some point; each of them are capable of acts of lawlessness and all sorts of violence. Shots are nothing.

Judge Gold hurls the sheriff’s words at Sabas and Refugio, thinking to himself, Now they won’t be able to pay me for who knows how long, but at least I have the pleasure of delivering bad news. But he immediately feels uncomfortable: the taunt was unnecessary, and he has nothing to gain from it. That’s Judge Gold for you, callous impulses and heartfelt regrets.

Nat, overhearing this interchange, rushes off to the Market Square to check out what’s happening with Nepomuceno and Shears.

Sabas and Refugio would have celebrated the humiliation of their mother’s golden boy but they can’t because the news has been delivered by Judge Gold with intent to wound. So they continue on their way as if nothing of consequence has been said.

Glevack, arriving from Mrs. Big’s Café, is about to approach Sabas and Refugio but stops abruptly and turns—he sees his chance to speak with Judge Gold.

A few seconds later Olga, a laundress who occasionally works for Doña Estefanía, approaches the brothers. She wants to tell them the news about Shears in hopes of patching things up with them but they’re annoyed with her because they’ve heard she’s told Doña Estefanía they don’t have her best interests at heart. Of course Olga was right, and everyone knows it (even Doña Estefanía, even Sabas and Refugio), but was it really necessary to spread such poisonous gossip?

The brothers ignore Olga and keep walking side-by-side, each wrapped in his own thoughts, each unaware the other is counting the seconds, the minutes, the hours till they can go to Stealman’s house, where they’ll discuss the Shears-Nepomuceno affair at length, each thinking to himself, We have to make it clear there’s a world of difference between us and that good-for-nothing, and worrying that if they go they run the risk of being snubbed. Damn Nepomuceno, that troublemaker. He had to stir things up today, just when we’re invited over there.

Olga tries Judge Gold. He too ignores her. Desperate for attention, she runs to tell Glevack, who is trying to catch up with Judge Gold, but Glevack forges ahead as if no one is there.

Glevack is in a bad mood, though for no good reason, since he is a primary beneficiary of the fraud against Doña Estefanía, which Nepomuceno is trying to reverse by legal means, the reason for his recent visit to the court. Indeed, it was Glevack who sweet-talked Doña Estefanía into making the deal with the gringos, knowing full well they would take advantage of her and that he would get part of the profit. Glevack would love to be the one to insult Nepomuceno in the Market Square, to call him a worthless nobody in front of everyone. He’s called him worse, the man who was his friend and associate.

Once Glevack had nearly got him thrown in jail. The two of them had hired a mule driver to steal back some livestock that Stealman had rustled from them. When the mule driver turned up dead on the steps of the Town Hall, people blamed Glevack and Nepomuceno. Glevack testified he had nothing to do with the murder, that it was all Nepomuceno’s doing. He gave lots of details and made up others, even saying that it was Nepomuceno who had robbed the mail.

Glevack should be relishing the insult, but it’s not in his nature to enjoy anything. And his perpetual foul humor has deepened because Judge Gold won’t stop and listen to him, and because he suspects that Sabas and Refugio are turning against him. He feels beset by problems.

Olga’s got her own worries. She’s no longer eighteen, twice that in fact. She’s lost her bloom. No one, not even Glevack, looks at her like they used to. When women lose their glow they’re like ghosts to men; out on the street, no one turns to admire them. Some feel liberated by this lack of interest, but others, like Olga, won’t stand for it, they’ll do anything for attention. So Olga crosses the main road, Elizabeth Street, walks to the intersection of Charles Street, and knocks on Minister Fear’s door.

It’s not yet a month since Olga helped unpack the trousseau of the minister’s new wife, Eleonor.

Although Eleonor is a recent bride, she is no spring chicken either: she’s past twenty. Her husband, Minister Fear, is forty-five; he had been a widower for two years when he placed an advertisement for a new wife. The ad, which appeared in papers in Tucson, California, and New York, stated in succinct English:

LONELY WIDOWER SEEKS WIFE TO ACCOMPANY METHODIST MINISTER ON THE SOUTHERN FRONTIER AND ASSIST WITH HIS WORK. PLEASE RESPOND TO LEE FEAR IN BRUNEVILLE, TEXAS.

Olga knocks impatiently on the Fears’ door a second time, so hard that the Smiths’ door pops open (their house is adjacent, on the corner of James, which runs parallel to Elizabeth), and out comes the lovely Moonbeam, an Asinai Indian (some call them the Tejas Indians, though the gringos call them Hasinai, part of the Caddo tribe). The Smiths bought her for next to nothing a few years back, before it became fashionable to have Indians as servants. Now they would have to pay twice as much. She’d be a bargain at any price: she’s beautiful and hard-working with a pleasant manner about her, though sometimes she gets distracted.

Moonbeam steps into the street. A second later, Eleonor Fear opens her door with an expression of befuddlement. Eleonor doesn’t speak a word of Spanish, but Olga makes herself understood. First, she offers her services—washing, cleaning, cooking—whatever the Fears might need. Eleonor declines amicably. Minister Fear arrives (curious to see who is at the door) as does Moonbeam (the Smiths’ young slave is always interested in gossip), and Olga tells them about the incident, using gestures to make herself understood: a five-pointed star for the sheriff, a violin and a lasso for Lázaro, but Nepomuceno’s name alone is enough, everyone knows who Don Nepomuceno is.

The Fears don’t show the least interest (the minister is too prudent, and Eleonor is wrapped up in her own world) but Moonbeam is captivated. She knows how stupid Sheriff Shears is—he came to fix the Smiths’ dining room table and left it even wobblier than before—and she thinks the world of handsome Nepomuceno (the Smiths’ daughter Caroline carries a torch for him, and Moonbeam does a little too, like all the young girls in Bruneville).

When Minister Fear closes the door, Olga turns and heads back to the market. Moonbeam glances up and down Elizabeth Street, looking for a reason not to go back inside the Smiths’ and finish her chores, when around the corner come Strong Water and Blue Falls, two Lipans—the Lipans are fiercer than most Indians, but friendly with the gringos—astride two handsome mounts, followed by a heavily loaded pinto mustang, a typical prairie horse (if someone offers a good price, it’s for sale).

Strong Water and Blue Falls are turning onto James Street to avoid Nepomuceno’s men; they haven’t come to Bruneville looking for trouble.

Despite the heat, the Lipans are in long, fitted sleeves with bright, colorful stripes, and they’re wearing embroidered moccasins. They have bands of colored beads tied around their foreheads and their necks; their long hair is adorned with feathers, leather strips, and rabbit tails; and they have embossed spurs.

Neither too slowly nor too quickly—she knows what she’s doing, the street’s her territory—Moonbeam approaches them. The Lipans dismount. Moonbeam mimes what has just happened in the Market Square, using the same gestures as Olga. Then she turns and goes back inside the Smiths’ house, slamming the door, which prevents her from hearing the second shot of the morning.

Strong Water and Blue Falls interpret the Shears-Nepomuceno incident in different ways. Strong Water thinks it means something has happened at the Lipan camp, and he wants to return immediately because this bodes ill for his people. Blue Falls, on the other hand, thinks it has nothing to do with the Lipans; he’s certain the only thing they should worry about is selling their wares according to the orders of Chief Little Rib, and besides, the shaman, being omniscient, will already know all about the incident.

Should they head home, like Strong Water urges, or stay and sell their goods, like Blue Falls wants? Nothing they have with them is perishable—Strong Water argues that skins, nuts, and rubber sap will keep for weeks. But the trip is long and tiring, says Blue Falls, and they need munitions back at camp; the two shotguns they plan to buy are not urgent purchases, but they would come in handy on the way home; they had to take many detours to avoid danger on the road to Bruneville, and it would be better to return armed.

The Lipans defend their points of view, arguing ever more vehemently. They start fighting. Strong Water pulls his knife.

Inside the Smiths’ home, lovely Moonbeam gets back to work, filling the bucket at the cistern to carry water to the kitchen.

Meanwhile, at the market, Sharp, the butcher, is roaring with laughter. “Nepomuceno! That cattle thief! Humiliated in public, in the Market Square! He had it coming!”

The label “cattle thief” requires explanation. Sharp believes the cow in question is his because he bought it, but Nepomuceno believes he is right to call it his own, because the animal was born and raised on (and bears the brand of) the ranch where he himself was born. “Sharp shouldn’t be so self-righteous,” he says, “because he knew perfectly well the cow was stolen, and the price he paid didn’t begin to compensate the value of such a heifer, he can peddle that argument somewhere else!” When word of what Nepomuceno was saying got around the Mrs. Big’s Hotel, Smiley said, “Does he think Sharp’s cow is his sister?!”

Sharp puts his knife on the chopping block, wipes his hands on his apron, and, without taking it off, strides over to the Plaza.

Let’s leave him there, because we should travel back in time to just before the Shears-Nepomuceno incident—to, say, 11:55 AM—to fill in some details that matter to us.

Roberto Cruz, the leather merchant whom everyone calls “Cruz,” has been waiting some time for the Lipans, watching the main road impatiently from his stall at the edge of the market. According to Cruz, the Lipan sell the highest-quality skins, and the best embroidered moccasins (which nobody buys besides some eccentric Germans), and incomparable leather leggings, which sell like hotcakes because the women can’t ride without them lest they chafe their private parts.

Two days earlier Cruz had bought a bunch of buckles and eyelets. Sitú, the kid who knows how to burn designs into belts (a new look that’s very popular), is waiting at home for the Lipans’ leather. Since the Lipan, like all prairie Indians, follow the lunar calendar, Cruz expects them shortly. If they don’t show up, Perla will start getting irritated because of Sitú sitting around, doing nothing, getting on her nerves. Perla is the girl who has kept house for him since his wife died and who he is determined to marry, as soon as his daughter gets hitched. He’s made up his mind though he hasn’t told anyone yet, not even her.

So there was Cruz, craning his neck, trying to spot the Lipans coming down Main Street, when Óscar passed by with his basket of bread on his head.

“Psst, Óscar, I’m talking to you! Gimme a sweet roll!”

“O.K., but only one per customer. I didn’t put much in the oven ’cause I thought it was going to be a slow day, and I have to hold on to enough to sell down at the docks.”

“O.K., just one.”

Cruz keeps craning his neck, scanning for the Lipans, while Óscar lowers his basket.

Óscar selects a crunchy bun covered with sugar (he knows what Cruz likes, it’s his favorite). Cruz pays him.

“Keep the change.”

“Nah, Cruz, you don’t have to do that.”

“Then put it toward my next bun.”

Óscar lifts the bread basket onto his head and leaves for the docks.

Tim Black comes out of Café Ronsard. He greets Cruz and gestures that he should bring over his belts. Tim Black is a wealthy Negro who, most unusually, owns land and slaves. When Texas gained its independence from Mexico in 1836 Negro landholders were disenfranchised when Texas’ Congress legalized slavery and imposed racial restrictions on owning property; Tim Black was granted an exemption from these laws by the new Congress.

Cruz puts his roll on the counter and slings a bunch of belts over his shoulder; they hang by their buckles from an iron hook in his hand.

At this moment, in the middle of the square Sheriff Shears shouts at Lázaro Rueda, the old vaquero, the one who knows how to play the violin, and whacks his forehead, hard, with the butt of his pistol. After the second or third blow, Lázaro falls to the ground.

Tim Black moves to see what’s happening. He doesn’t understand Spanish, which leaves him clueless about much that happens on the frontier, but no language is needed to know exactly what’s going on: a poor old man is being beaten senseless by the sheriff.

Nepomuceno exits Café Ronsard and he, too, encounters the scene with Shears. He recognizes Lázaro Rueda instantly and decides to intervene.

Black watches Nepomuceno’s reaction, hears his calm tone, catches the drift of his words—with the help of Joe Lieder, the German kid who repeats everything in his broken English—and hears the sharpness of Shears’ insulting response: “Shut up, you dirty greaser.”

The merchant ship Margarita’s horn sounds, announcing her imminent departure.

On the other side of the square, Óscar hears the words Shears spits at Nepomuceno and sees out of the corner of his eye what’s happening, but his sense of duty is greater than his curiosity; if the Margarita has sounded her horn he barely has time to get down to the docks and if he doesn’t speed up they won’t get their bread. He hurries away.

Don Jacinto, the saddler, crosses the square toward Café Ronsard carrying his new creation, “a really fancy one.” (He’s from Zacatecas, and he’s been married three times. Two days a week he works in Bruneville, the rest of the time he’s across the river in Matasánchez. Business is good.) He announces to one and all, “I want to show this one to Don Nepomuceno. No one else will appreciate its fine workmanship like him.” Everyone knows that if Nepomuceno expresses his admiration it will fetch a better price. No one knows more about saddles and reins, no one handles a lasso or rides as well. It’s not so much that horses obey him as they have a mutual understanding.

Don Jacinto is near-sighted and can’t see more than two yards in front of him or he would have witnessed the scene as well. But he’s not deaf; he hears the blows clearly, and Nepomuceno’s words, and Shears’ response, which stops him in his tracks. He can’t believe the carpenter would speak to Don Nepomuceno that way.

Peter, whom the Mexicans call “El Sombrerito,” owns the hat shop. His original surname being unpronounceable, he changed it to “Hat” for the gringos: “Peter Hat, hats of felt, and also of palm, for the heat.” He is hanging a new mirror on the column in the middle of his store when, in the mirror’s reflection, he sees Shears pistol-whipping Lázaro Rueda, “the violinist vaquero” (a vaquero being a Mexican cowboy). He also sees Nepomuceno approach, and the kid who goes around with La Plange, the one they call “Snotty,” running toward them. His instincts tell him something bad’s about to go down. He takes down the mirror (“Why, Mr. Hat?” asks Bill, his assistant, “It was almost straight.”), stowing it safely behind the counter, and sends Bill home with a few coins. (“Help me close up shop and skedaddle! And don’t come back to work till I send for you!”). He lowers the blinds and locks the front doors of his establishment, crosses the threshold that separates the store from his home, double bolts the door from inside and shouts to his wife, “Michaela! Tell the kids not to go outside, not even on the patio, and lock all the windows and doors; no one sets foot outdoors until this storm blows over.”

Peter Hat goes to the patio and cuts two white roses with his pocketknife and takes them to his altar to the Virgin, next to the front door. He kneels on the prayer stool and begins to pray out loud. Michaela and the children join him; she takes the roses from his hand and puts one in a delicate blue vase, the same color as the Virgin’s robes, and the other in her husband’s buttonhole.

Mother and children begin drowning their worries in hurried Hail Marys.

But Peter, the more he prays the more worried he gets. His soul is like a poorly woven hat, full of imperfections.

Before leaving, tow-headed Bill had just stared at Peter, unable to understand what had upset him, unable to help.

Out in the street he adjusts his suspenders. He’s spent every penny he’s ever earned working for Peter on these expensive, trendy suspenders.

He soon catches on to what’s happening down in the market, and, instead of heading home, he runs across the square to the jailhouse.

His uncle, Ranger Neals (who oversees the prison and is highly regarded), listens closely to Bill’s report.

“That idiot Shears … insulting Nepomuceno is gonna land us all in a heap of shit.”

Others arrive at the jailhouse door, fast on Bill’s heels: Ranger Phil, Ranger Ralph, Ranger Bob. They’re bearing the same news, and they arrive just in time to hear him say to his nephew:

“Let’s sit tight, no one makes a move, got it?”

They don’t stick around to hear the rest. They run to relay orders to the other Rangers.

“We don’t want to start a wildfire. This is a bad business.”

Urrutia is the prize prisoner in Bruneville’s jail. He’s one of a gang of bandits who help fugitive slaves cross the Rio Grande. The minute they set foot on Mexican soil they become free men by law. Urrutia lures them with the promise of land in Tabasco. He shows them contracts that are more fairy-tale than anything else. He describes fertile land, wide canals, cocoa plants growing beneath shady mango trees, sugar cane. He’s vague about the exact size and location, but that doesn’t matter, given such promising prospects.

Urrutia does take them to Tabasco. The landscape is exactly as he described. But the reality is different. Urrutia has valid contracts that commit them to indentured servitude and maltreatment—it might as well be imprisonment. The lucky ones die from fever or starvation before the first whipping.

Urrutia’s men have made a fortune doing this. Sometimes, when a slave has unusual value, they return him to his original owner for a ransom. They even brag about the free Negros they catch in their net, selling them at a premium because, being strong and healthy, “they make good foremen.”

Urrutia is guarded by three gringos who get paid extra wages because the mayor suspects Urrutia’s accomplices—numerous and well-armed—will try to rescue him (we’ll get to the mayor’s story later; suffice it to say that the notion he’s been elected by popular vote is preposterous). The three guards, whose names can’t be divulged, overhear the story of the insult without paying it much attention. They’re only here for the money (which isn’t always paid on time, to the chagrin of their families); if Nepomuceno offered them more money they’d work for him, despite the fact that they’re gringos.

When Urrutia hears about Shears and Nepomuceno, a sudden change comes over him; he’s like an autumn leaf about to fall from the tree. And for good reason.

Werbenski’s pawn shop sits between the jailhouse and the hat shop. It’s not a bad business, but the really profitable part takes place at the back of the store: the sale of ammunition and firearms. Werbenski doesn’t go by his real name to hide the fact that he’s Jewish—no one knows where he came from. Peter Hat can’t stand him, Stealman takes no notice of him (but Stealman’s men do business with him, same as Judge Gold and Mr. King). He’s married to Lupis Martínez, a Mexican, of course—“What can I do for you, sir?”—the sweetest wife in all of Bruneville, a real gem, and a smart one, too.

Like Peter Hat, Werbenski senses there will be repercussions from the Shears-Nepomuceno affair, but he doesn’t shut up shop. He tells Lupis to get to the market quickly, before things get really bad.

“But sweetie pie, we went early this morning.”

“Stock up. Buy all the dry goods you can. Get bones for the soup.”

“We’ve got rice, beans, onions, potatoes, and we’ve got tomatoes and peppers for salsa growing in the back. There’s water in the well …”

“Get some bones, for the boy.”

“Don’t worry, sugar plum, the chicks are growing up, the hen is laying eggs, we’ve got the two roosters, though one is old; there’s the boy’s rabbit, and the duck that mother gave me. The turtle is hiding somewhere, but if we get hungry I’ll root it out, and if I can’t find it I’ll stew up the iguanas and lizards like my aunts do.”

The last bit was intended to make her husband smile, but he wasn’t even listening; neither of them could stand Aunt Lina’s iguana stew, not because of the way it tasted but on account of skinning the animals alive. Werbenski’s head is reeling, but he takes comfort in the fact that they baptized his boy. They may do what they want with a Jew, but my wife and my son must be saved. Lupis reads his mind.

“Don’t worry sweetie pie.”

Lupis adores him. She’s naturally sweet-natured, but she knows she’s got the best husband in all Bruneville—the most respectful, most generous, most sensible. A Jewish husband is worth his weight in gold.

There’s a pleasant breeze down at Bruneville’s docks, but up at the market and in the Town Hall—why lie?—it’s like being inside a Dutch oven. Short distances from the river make a big difference. Crossing it makes an even bigger difference; the Great Plains end here, bordered by the Río Bravo to the south. On the other side they also have people of all stripes—Indians, cowboys, bandits, Negros, Mexicans, gringos—as well as profitable mines and endless acres of land, but it’s different. The Río Bravo divides the world in two, perhaps even three or more. No fool would say that the gringos are all on one side and the Mexicans on the other, with separate territories for the Indians, the Negros, and even for sonsofbitches. None of these categories is absolute. In the Indian Territory there are many different tribes that don’t get along, they’ve just been shunted there by the gringos, just as there are also Negroes who speak different languages. Not all gringos are thieves, and not all Mexicans are kind-hearted; each of these groups have both good and bad.

Nevertheless, it’s an indisputable fact that the Río Bravo marks a border, because on its northern bank the Great Plains begin, and on its southern bank the world becomes itself again: the Earth, abounding with variety.

When he arrives at Bruneville’s dock, before taking his basket of bread off his head, Óscar announces loudly what Shears, the crappy carpenter (and even worse sheriff), has said to Nepomuceno. He’s overheard by Santiago the fisherman, who has just emptied his last basketful of crabs into Hector’s cart (it rained all night, which explains his unusually large catch). Santiago’s three children, Melón, Dolores, and Dimas, sit on the cart’s edge, their feet dangling just out of reach of the crabs. They are binding their claws and bunching them into bundles of a half-dozen each—they’ve spent the whole morning at the task. The vaqueros Tadeo and Mateo hear Óscar, too. Their livestock is already aboard the barge heading for New Orleans once it stops across the river to load the animals’ feed and some crates of ceramics from Puebla by way of Veracruz. They’re ready to feed their hunger and slake their thirst, to relieve their tiredness and boredom from the isolation of the pastures.

The cart’s driver, Mr. Wheel, doesn’t speak Spanish; he doesn’t understand a word Óscar says and neither does he care. No sooner has he gotten underway—passing through the neighborhood where the homes have roofs of reed or thatched palm, and the walls are made of mesquite or sticks, where they eat colorín flour or queso de tuna (which doesn’t deserve to be called cheese)—than Santiago’s kids start shouting, “Crabs! Crabs!”, working the phrase “dirty greaser” into their sales pitch, all the while deftly trussing up their remaining captives. They enter the part of town where the houses are made of brick, and they continue pitching their wares and spreading gossip.

Santiago passes the story to the other fishermen, who are detangling their nets for tomorrow’s early return to the water, leaving them laid out on the ground.

The fishermen carry the news along the riverbanks.

The vaqueros, Tadeo and Mateo, go straight to tell Mrs. Big, the innkeeper—it’s said she fell in love with Zachary Taylor in Florida and followed him to Texas, and that when he went to fight in Mexico she moved down to Bruneville, where she opened her waterfront hotel: cheap, but with pretentions to class, it has a dining room, bar, “casino,” and “café.” Word is that when some gossipmonger came to tell her that the Mexicans had killed her Zachary, she spat back, “You damn sonofabitch, there aren’t enough Mexicans in all Mexico to kill old man Taylor.” Driving the point home she added: “I’m gonna rip open your foot and give you a new mouth down there. You understand? Let’s see if you can learn to tell the truth with your new mouth, and stop spreading lies with the one you’ve had since birth.”

Mrs. Big tells the story about Nepomuceno and Shears to Lucrecia, the cook. Lucrecia tells the kitchen hand, Perdido. Perdido tells all the guests. Mrs. Big celebrates the news by offering a round on the house.

Why is she celebrating? Because she doesn’t like Mexicans? Or is it vengeance, settling unpaid debts? It’s a little of both, but the main reason is that Nepomuceno patronizes her rival, the Café Ronsard, her competition, her enemy, the focus of all her envy, the testament to all the mistakes she’s made, the burden she bears daily. She’s the best cardsharp in all Bruneville, no one can beat her at blackjack. Her view of the river is better; there’s a good breeze, and she’s got an old icaco tree, which gives great shade. So why doesn’t she have the best café? The Ronsard doesn’t have any of this, “just stinking drunks, lying around outside in the dirt.” Mrs. Big even plants tulips in the spring, and her roses bloom year-round (though when it’s burning up, their petals literally roast in the heat).

The two vaqueros spread Shears’ insult, embellishing it along the way. Tadeo steps into one of Mrs. Big’s rooms and passes the news on to two whores, the Flamenca sisters, with whom he’s about to begin a relationship that’s almost brotherly. Mateo tells both of his girlfriends. First, his publicly recognized one, Clara, the trapper’s daughter (she was waiting for him down by the dock), and then he tells his secret girlfriend, Perla, Cruz’s housekeeper, whom Mateo has sweet-talked into bed. She really does it for Mateo, she has a sweet ass and boy does she know how to use it, even better than Sandy can. But let’s be honest, she’s no looker.

A little later, Mrs. Big tells her fellow card players about the “Shears-Nepomuceno Affair,” while one of the Flamenca sisters muddles the story in the hotel bar. Tadeo remains in the room with her sister, it’s taking him a while to get it up.

Three people are playing cards with Mrs. Big: Jim Smiley, a compulsive gambler (he’s got a cardboard box with a toad next to him, for a while now he’s been trying to train it to jump farther than any other); Hector López (who has a round, childlike face, is an incurable womanizer, and owns the cart in which the trussed-up crabs are making the rounds of Bruneville); and one other guy who never opens his mouth, Leno (he’s desperate, and is only here to try to win some money).

On one side of the table, Tiburcio, the sour, wrinkled old widower, is watching them play; he’s always got some comment as bitter as his breath on the tip of his tongue.

Captain William Boyle, an Englishman, is the first of the dozen seamen who are about to set sail on the Margarita to understand the insult—most of them don’t speak a word of Spanish—and he translates it back into the sheriff’s mother-tongue, though his rendering alters it somewhat: “None of your business, you damned Mexican.”

The sailors celebrate the insult, “At last someone put the greasers in their place.” Rick and Chris embrace and begin to dance, singing “You damn Meexican! You damn Meeexican!” in a joking tone that carries across the water. Before the day is over, people on both banks of the Rio Grande, from Bruneville to Puerto Bagdad will have heard about what the gringo sheriff said, more or less accurately.

From Puerto Bagdad the news sails out into the Gulf, on boats headed north. After passing Point Isabel, the story runs up the coast, working its way past one river delta after another, and it’s carried upstream on the Nueces, the San Antonio, the Guadalupe, the Lavaca, the Colorado, the Brazos, the San Jacinto, and the Trinity.

And from a rotting dock the news travels with the mail boy to New Braunfels. The Germans are the only ones who give the mail carriers more work than the gringos.

In Galveston, no sooner has the phrase made it off the boat than it doubles back southward, finding passage on a steamboat that’s just arrived from Houston and is headed to Puerto Bagdad, Mexico, almost directly across the river from Point Isabel, Bruneville’s seaport. The majority of the passengers are Germans who’ve spent the better part of the trip’s first leg singing songs from the old country, accompanied by a violin, a horn, and a guitar. They even have a piano on board, but no one can play it because it’s wrapped for shipping.

One passenger, Doctor Schulz, is one of the famous Forty, the Germans who came to the New World to build a new world. In 1847 he helped establish the colony of Bettina (named after Bettina von Arnim, the writer, composer, social activist, publisher, patron of the arts, and acolyte of Goethe—“My soul is an impassioned dancer”). In Bettina there were three rules: Friendship, Freedom, and Equality. No man was treated differently from the next; there was no such thing as private property; and they all slept together in a long house that wasn’t remotely European, with a thatched roof and a tree trunk in the center. The butcher prepared wild boar for the communal table.

Each of the Forty wore beards. The youngest was seventeen and the two eldest were twenty-four, free thinkers one and all. No one knows why they lasted only one year. There are lots of stories: some say that they harvested only six ears of corn because no one wanted to do any work (it’s true they spent most afternoons guzzling whiskey from barrels they had brought from Hamburg), while others say it was because of a woman, which makes no sense, because there weren’t any women in the colony.

When the community disbanded, the piano itself proved a source of friction. Schulz asked to take it—it had been a present from his mother—but because “everything belongs to everyone” it was nearly chopped up into pieces. In the end, the piano, which had accompanied the doctor on his long voyage from Germany, is making its way with him to Mexico. This part of his travels has taken a good long while. Schulz plans to set up shop as a doctor in Puerto Bagdad, where the piano will once again be played.

Another German passenger, Engineer Schleiche, began the trip from Houston half-heartedly, and by the time he arrives in Galveston he’s decided that life without his Texan girlfriend would be empty, meaningless. He decides to jump ship and wait for the next steamboat to New York, where the girl has fled, tired of waiting years for a marriage proposal that never came.

Although Schleiche finds Galveston beautiful—and it is—he is disgusted by the loose morals of its locals. He is at his hotel, giving instructions about having meals delivered to his room (he’s decided not to set foot outside until the steamboat is ready to depart “this den of iniquity”), when he hears about Shears’ insult and who the sheriff is; he already knows all about Nepomuceno. Fearing the worst, he instantly shuts himself in his room, so he’s not up to date on everything else that happens, and arrives in New York with only the first words uttered by Shears.

Schleiche was not one of the founding Forty from Bettina; as assistant to Prince Solms, he arrived in an earlier Prussian migration from the Adelsverein, or Society of Noblemen, the aristocrats who founded the Nassau Plantation in ’45 (his godfather was the Prince of Nassau). The nobles acquired land and servants (they bought twenty-five slaves) but the society broke up a few years later, for reasons different from those of the Forty.

Generally speaking, the Germans were appalled that a gringo sheriff would insult such a well-respected Mexican—you could say what you want about Nepumuceno but no Prussian would ever accuse him of stealing a cow. (Admittedly the Germans were clueless about cattle; they were useless when it came to livestock—“If a Kartofel lays a hand on a cow, she keels over.”)

When the third-class carpenter-sheriff came out with his little insult in 1859, it was only 24 years since Texas had declared and won its independence from Mexico, through a series of skirmishes and battles, some of which were fought more fiercely than others, and both sides have continued to accuse each other of atrocities ever since. Say what you will, the truth is the Texans won the war by river and by sea because the Mexicans didn’t have a navy to speak of; during the entire Spanish occupation not one Mexican was trained to lead a flotilla, and they didn’t have any boats anyway.

Texas declared its independence in 1835. Since the Mexicans had invited Americans to live on large tracts of their land, granting them land concessions at very favorable rates, this declaration didn’t sit well with them. That’s why the military confrontations, skirmishes, and battles between Mexicans and Texans didn’t stop.

In ’38, more than a thousand Comanches coordinated attacks south of the Río Bravo on ranches, towns, and settlements. Since the Texan rebellion, not one Mexican had been able to go out and kill Comanches and Apaches in the Indian Territory—it had become impossible to cross the Republic of Texas because the warlike tribes were running roughshod over the countryside, stirred up by the arrival of new tribes from the north and the disappearance of the buffalo.

In ’39, the Texan Congress gathered in Austin, which was declared the capital of the Republic. Skirmishes continued.

In ’41, two thousand Texan soldiers were taken prisoner by the Mexicans and incarcerated in Mexico City.

In ’45, Texas was annexed by the United States. It went from being an independent republic to becoming one of many stars on a foreign flag. Although it seemed like a terrible idea, it wasn’t bad at all, because it completely changed the balance of power with Mexico. The struggle for the Texan frontier worsened. The Texans argued that everything from the Nueces River to the Rio Grande was theirs. The Mexicans denied the claim, saying that it wasn’t in their previous agreement.

And that’s how it came to pass that the American army invaded Mexican territory in 1846. Shortly thereafter they declared victory and took over the disputed territory, and the land between the Nueces River and the Rio Grande was no longer Mexican.

Throughout these war-torn years, Doña Estefanía was the one and only legitimate owner of the land called Espíritu Santo, which extended far into the territory that became American. It made no difference that she was a savvy landowner, with herds of livestock and good harvests (mostly beans, but she had different crops on her other ranches). Stealman arranged to carve off a healthy (and profitable) portion of her lands. And it was on this profitable stretch of land that he established Bruneville, selling plots at inflated prices, which was a great business.

Eleven years have passed since the town of Bruneville was founded on the banks of the Río Bravo, just a few miles upriver from the Gulf. It was named after Ciudad Bruneville, the legendary shining city to the northwest, which was razed by the Apaches. In appropriating the name, Stealman aimed to trade on the good reputation of the original.

At its founding, the following were present (without a shadow of a doubt):

A Stealman, the lawyer;

B Kenedy, who owned the cotton plantation;

C Judge Gold (back then he was just plain Gold, he hadn’t yet earned the nickname Judge);

D Minster Fear, his first wife, and their daughter Esther (may the latter two rest in peace);

E A pioneer named King.

King had a royal name, but when he’d arrived in Mexico he hadn’t a penny, he didn’t even own a snake. But he had the Midas touch. When some locals lent him low-grade land to use for seven years, it took him only a few months to emerge as the legitimate owner of immense tracts on which it seemed to rain cattle from the clouds, as if they were a gift from God. But there was nothing remotely miraculous about the way King made his fortune. He was as good a trickster as any magician with a false-bottomed top hat. If King had been Catholic (as he claimed to be in the contract he signed with the Mexicans), the archdiocese could have been able to build a cathedral with what he’d have paid for his sins.

In 1848 King wasn’t the only one who went looking for a fortune, convinced that “Americans” had the right to take what belonged to the northern Mexicans by whatever means necessary.

A year after it was founded, Bruneville suffered its first outbreak of cholera. The epidemic claimed the lives of one hundred citizens and almost choked the life out of the region’s economy. Around that time, the rumor was that Nepomuceno robbed a train west of Rancho del Carmen and sold its cargo in Mexico. If it’s true, he was only making up for the many robberies he had suffered.

That same year, to the northeast of Bruneville, Jim Smiley arrived at the camp of Boomerang Mine, which was played out, and discovered his addiction to gambling.

Just across the Rio Grande the city that Brunevillians called their twin, Matasánchez, prohibited several things:

1 Fandangos;

2 Firing weapons in the street;

3 Riding horseback on the sidewalks; and

4 Any animals at all on the sidewalks.

The arrogant Brunevillians applauded these measures, saying, “At last they’re leaving their uncivilized ways behind.” Which was a bit much, given that Brunevillians half-drowned in mud each time it rained and suffocated on dust every dry season, their city being so poorly constructed. When all was said and done they were just a handful of palefaces, struggling to cope with a sun that assaulted their senses, yet they acted like they were the center of the world. (Matasánchez, on the other hand, was something to see.)

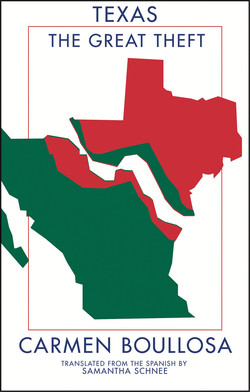

Bruneville was two years old when an assembly took place at which the new land-grabbers, led by King, played the Great Trick on the Mexicans—a.k.a. the Great Theft—dispossessing them of their property titles by pretending that the new state was legitimizing them. The citizens of Bruneville thought this was a good move; they believed the law was going to protect them, but they were quickly disabused of this notion.

The truth is that the gringos took advantage of several things:

A The Mexicans didn’t speak English;

B The Mexicans were given citizenship and told they had rights; but

C The rights meant zilch unless they could be defended in a court; and

D The lawyers who were supposed to defend them were thieves, stealing land that had been owned, inherited, or worked by their clients for generations.

The gringos stole and proceeded to act like they were the legitimate owners of what they had stolen.

This is the truth, the whole truth, and nothing but the truth.

This was also the year of the yellow fever.

Bruneville now had a population of 519 (in Matasánchez there were 7,000, half of what there had been before several wars and two hurricanes hit the region before Bruneville even came into being). It’s worth mentioning that most gringo Brunevillians knew nothing about the neighboring town, and could not have cared less.

Bruneville’s third year was just more of the same.

Bruneville was four years old when its population doubled. Pioneers from the north arrived by the boatload, prepared to do anything to make their fortunes. At the same time, penniless Mexicans fleeing the troubles in the south were crossing the river, looking for a way to make a living. More of these folks went north than runaway slaves went south to find their freedom. Bruneville’s reputation as a den of thieves (or a land of opportunity) grew. Where there are thieves there’s loot, the smell of easy money.

The Mexicans set up portable grills on street corners everywhere over which they cooked their own food and more to sell.

In the Rio Grande Valley, the theft of Mexican livestock was a daily practice, like picking herbs or berries in a forest. The branded cattle and shod horses might as well have been mustangs and mavericks, they were treated no differently; and there were plenty of animals for the taking—grabbing strays when possible, taking them at gun point if not. Armed bandits roamed the land, crossing the Rio Grande to drive livestock northward from the south.

Bruneville’s fifth birthday was celebrated with the construction of a lighthouse at Point Isabel, its seaport. A group of Brunevillians proposed naming the lighthouse Bettina, after Bettina Von Arnim, who had recently passed away: “beautiful and wise, the embodiment of the powers of nature.” The Germans, the Cubans, and a pair of Anglos held a memorial service in her honor and placed a gravestone in the community gardens: “She had a remarkable amount of energy, which she radiated upon everyone around her; she was equally at home with people and with nature; she loved the damp earth and the flowers that bloomed in it.” But the Texan authorities were both ignorant and reactionary—though claiming to be republican and liberal they were in fact diehard defenders of slavery—and sent them packing.

Bruneville was six years old when a law was passed prohibiting the employment of Mexican laborers. But the law wasn’t enforced because no one was better at taming and caring for horses, and keeping house too.

When Bruneville turned eight, four dozen camels arrived. Some say they were intended for the ranches, where it was thought their humps would enable them to survive both heat and drought. They were also rumored to be a cover for slave trading; a witness swore to having seen young men, women, and children arriving on the same ship.

Two camels, a male and a female, continued their travels by water, heading upriver on another boat, while the rest hoofed it to their final destinations; except one, a pregnant camel, which was bought by Don Jacinto, the saddler, though it died shortly thereafter of unknown causes, before giving birth. Minister Fear declared this a manifestation of God’s wrath, though the reasons for such wrath remained unspecified. Father Rigoberto said this was absurd; he usually took care not to contradict gringos, but this was going too far. This was the year that Father Rigoberto chose to follow orders of the Archbishop of Durango instead of those of the Galveston diocese, which served only to leave the parish worse off than it had been before.

Before we abandon the camels, it should be noted that witnesses had still another story about how they came to be in Texas: they were imported by the army, which planned to use them against the Indians.

Bruneville was about to celebrate its ninth birthday when Jeremiah Galván’s store by the river burned down. Many people suspected it was arson. There were ninety-five barrels of gunpowder on the second floor of the store. The explosion destroyed the neighboring buildings, blew out all the windows in Bruneville, and even rattled doors in Matasánchez. Soldiers, Rangers, and citizens all lent a hand dousing the building with water from the river, pumped by steamboats, in an effort to control the fire before the flames made it all the way up Elizabeth Street to the Town Hall, razing four square blocks in the process.

At the Smiths’ house, a spark landed on the mosquito net in Caroline’s room; it went up in flames in the blink of an eye (it was very fine netting). Some say it left Caroline a little touched in the head; but others said she hadn’t been quite right since birth.

Another outbreak of yellow fever hit Bruneville on its tenth anniversary. That was the year the legend of La Llorona (The Wailing Ghost) became popular; though most gringos pooh-poohed the story, more than one swore they had seen her walking the streets, wailing, “Ay, mis hijos!” “Where are my children?”

That same year some gringos from the north, where it’s hideously cold, arrived hungry and eager. They were four brothers, skinnier than mine mules, with the last name Robin; all they had in common aside from their last name was their good looks, and their being skinnier than skeletons. The eldest was a redhead. The next one had black hair. The third had hair that was curly and blond. And the fourth, the youngest, barely had any hair at all, just a little transparent peach fuzz.

The Robins gaped at the land of milk and honey, salivating as if there were sausages hanging from the trees (not that there were many trees, only mesquites and acacias, but the Robins had had enough of pines and spruces, which didn’t bear fruit or provide homes for honeybees). They saw that the wealthy Mexicans on the north bank had nice ranches, fattened livestock, arable land, and people who knew to care for both land and animals. They searched out judges and mayors who could be bought—in Texas corruption was widespread—and then set about taking a piece of it all for themselves.

Since this was a civilized land, the Mexicans weren’t prepared to deal with these professional thieves.

The brothers were tipped off about their first hit, and it wasn’t just any hit, it was a mail coach full of gold and gifts the miners out west were sending back home to their mothers, uncles, children, fiancées, sisters, friends, priests, and even nuns.

This first robbery filled their wallets, and allowed them to stock up on guns and ammunition. Now, armed, dangerous, and with the law in their pocket, they set to work (it must also be mentioned that though the Robins detest Indians, Negros, and Mexicans equally, they don’t let such prejudices get in the way of business; nothing matters to them more than money).

ACROSS THE RIVER LIES MATASÁNCHEZ, the city that Bruneville (talking out its ass) calls its twin. It isn’t true. Long before the Iberians set foot on the land, Matasánchez was founded by the Cohuiltecas, after whom came the Chichimecs, and then the Olmecs, and then the Huastecs, who built their trojes (their elegant barns), and brought their markets, dances, traditional cuisine, and prayer circles. It would be more correct to say that Matasánchez is Bruneville’s grandmother, or if you were to stretch the truth, Bruneville’s mother, with one caveat: Bruneville and Matasánchez have nothing in common.

In 1774, the town was baptized by the Spaniards as Ciudad Refugio de San Juan de los Esteros Hermosos. A mass was celebrated and everyone had tamales and liquor that had recently been shipped across the ocean. When the liquor ran out they began drinking sotol, tequila from the north. They spent the evening playing music and dancing; and from that night on, the city was famed for its fandangos. Its carnivals were also something to see; people of all stripes showed up: men looking for men; maricones who were happy to oblige; prostitutes a little long in the tooth; as well as ones who had recently been bought by their pimps. There were marimbas everywhere—that peculiar half piano, half drum—and street musicians who were always coming up with new ditties. Like their peers in the south, sometimes they called themselves jaraneros, other times minstrels, and on other occasions balladeers. They liked to change their name, just like they changed their ballads, their verses, letting their imagination dance.

They built some gorgeous houses, and even palaces. The church was something to see, as was the central plaza, with an arched, covered walkway surrounding it.

Life in Ciudad Refugio (Matasánchez) was anything but boring. It was attacked by English, Dutch, and French corsairs and pirates. Indian warriors also left their mark. But the citizens were peaceful folk: they were into farming, harvesting, marketing, partying. So instead of fighting with the pirates they did business with them.

They tried this with the Indians, too, but it didn’t work so well.

In celebration of Mexico winning its independence from Spain, the town’s name was changed from Nuestra Señora del Refugio de los Esteros to Matasánchez, in honor of the man who ended the threat posed by the Trece brothers, two arrogant pirates. But we should get back to Nepomuceno and Shears, the story of the highfalutin Trece brothers will have to wait.

When the Anglos from the north became more hostile to the Indians, pushing them into Indian Territory, the whole region bore the brunt of their fury. How could they not be furious? But there was no time to take their feelings into account; folks had to defend themselves or else all the males would have been scalped and chopped to pieces, the women raped and sold. But there weren’t enough walls, moats, and other defenses to protect them. It became necessary to: “Pursue them the way they pursue us; harass them the way they harass us; threaten them the way they threaten us; attack them the way they attack us; rob them the way they rob from us; capture them the way they capture us; terrorize them they way they terrorize us.”

The first challenge was being slowed down by the supplies that burdened them. The livestock they brought along to eat slowed them even more, and there was a risk that the Indians would drain the watering holes or poison them with the cadavers of their prisoners, or even their own horses, before the Mexicans reached them. That’s why, in 1834, the Mexican authorities came to an arrangement with the Cherokees and other tribes, offering them land, the opportunity to trade, and even livestock. One year later, 300 Comanches stopped in San Antonio en route to Matasánchez to sign a peace treaty with Mexico but the deal fell through. The day eventually came when the Mexicans began trading with them, and that was the end of the Indian threat, at least for a short time.

ON THE DAY that the Shears-Nepomuceno incident took place, Matasánchez celebrated its 85TH anniversary as a Christian town.

Who knows how big the population was in that year of our lord 1859, no one had counted heads recently. To hazard a guess, it was around eight thousand, if not more.

Matasánchez is, and always has been, the big city of the region. Bruneville doesn’t even come close. Eleven years ago, Bruneville was nothing more than a dock on the north bank of the river, used only when the city’s docks were full, or for goods that were en route to a ranch to the north, unless they were headed to the Santa Fe Trail, in which case it was better to continue even further up the muddy river.

Matasánchez, on the other hand, continued to grow, blessed with endless showers of riches. Here’s one example from the era when the Spanish were still in charge: for ten years Matasánchez had the export license for all Mexican silver; the customs office earned a fortune (seven out of every ten ships that docked in New Orleans originated in Matasánchez), and despite the facts that (as previously mentioned) hurricane after hurricane battered the city and regional conflicts cut the population in half, Matasánchez continued to be the principal metropolis and beating heart of the region.

When Bruneville was founded, Matasánchez converted one of its docks, down where the Río Bravo meets the sea, into its principal port. They christened it Bagdad. Bagdad quickly became wealthy, because that’s where the customs house was located, and there was a tremendous amount of traffic.

In fact, no sooner has Sheriff Shears uttered the now-infamous phrase than the dove-keeper Nicolaso Rodríguez scrawls it on a piece of paper, which he folds and slips into the ring around Favorita’s foot. She’s his favorite of all the messenger pigeons that fly back and forth between Bruneville and Matasánchez every day, carrying all sorts of messages: “The Frenchie dry goods vendor wants to know if they want beans.” “Need strychnine urgently; please send on next ferry. Rosita’s in a bad way.” “From the priest to the nuns: bake some more host quickly. We ran out and soon we’ll have to use bread as a substitute.” (This particular message caused a commotion at the convent; one nun swore that unleavened bread attracted the devil and claimed to have “scientific proof” of this, because in San Luis Potosí the mayor’s wife had become delirious after taking unleavened bread for communion when the host ran out.) “Fetch my daughter from the afternoon ferry.” “Don’t come, the steamboat has already left for Point Isabel.” If the message said “Rigoberto” it wasn’t good news—the priest’s name was used when some unhappy soul needed the last rites, on either side of the river; for example, “Rigoberto to Oaks” or “Rigoberto to Rita” or just “Rigoberto” when everyone knew who was at death’s door.

Favorita has shiny eyes and tiny pupils, she’s the cleverest pigeon; nothing distracts her. On Favorita’s foot Shears’ phrase crosses the river, over the levees, over Fort Paredes and its casemate, over the moat and the sentry boxes, all of which Matasánchez had built to try to keep the prairie Indians, the mercenaries, the pirates, and the river at bay. She arrives in the center of the town where Don Nepomuceno is so deeply and widely respected, and alights on the eaves of the courtyard behind Aunt Cuca’s house, where the other Rodríguez, Nicolaso’s brother Catalino, keeps Matasánchez’s dovecote.

Favorita is their favorite for good reason. Without entering the dovecote, she pecks on the door, which rings the bell. Catalino takes the message from her and, her work done, Favorita enters the dovecote. Catalino takes the message to the central patio.

The sun above Matasánchez is the same one that’s roasting Bruneville.

In the middle of the courtyard Catalino Rodríguez reads the message aloud for all to hear, including:

1 Aunt Cuca (who is crocheting in her rocking chair on the balcony outside the living room).

2 The women in the kitchen (who are making tamales; two of them are kneading the hominy while one of them adds small pats of lard, until it makes a paste with the maize flour that they use as a base, while Lucha and Amalia cut the banana leaves that they’ll roast over the fire).

3 Doctor Velafuente (who’s in his office).

4 And his patient (whose name we can’t reveal because he was seeing the doctor for a malady he picked up in an encounter off a noisy street in New Orleans, where he should never have set foot, but the deed is done).

Aunt Cuca sets her crocheting aside, puts on her shawl and goes to tell her godmother the news. Lucha and Amalia leave the kitchen on an urgent trip to the market: “We’re just going to get another quarter-ream of banana leaves, there aren’t enough for the tamales.” Doctor Velafuente ends his appointment; the patient leaves quickly for the church and the Doctor heads to the arcade. Each of them will go spread the word about how the Sheriff has insulted Don Nepomuceno.

The news is like a bomb going off in Matasánchez. The city wonders, How could a dirtbag like Shears (who was nothing more than a carpenter’s apprentice, and a bad one) speak like that to Don Nepomuceno?

But this general sentiment doesn’t mean that people don’t have bones to pick with Nepomuceno.

The old ladies who attend mass every day, shrouded in black, pray for Nepomuceno but wonder if the insult might be punishment “for doing things that embarrassed Doña Estefanía”; they haven’t forgiven him for romancing the widow Isa sixteen years ago when he was fifteen, or for the way his marriage to his cousin Rafaela ended (he had agreed to it reluctantly, only to please his mother). When Rafaela died in childbirth they blamed him: “How could she have survived the ordeal with her broken heart?” (Some people swore that she hadn’t been kissed during the entire marriage, and that Nepomuceno did it to her quickly just to get her with child. Although others said—out of maliciousness, no doubt—that she had already been with child when they wed.) Nor had they forgiven him for his subsequent marriage to his former lover, Isa, the widow who bore him his first daughter (they’re still married); nor for the other dalliances people whisper about on the way out of mass.

On the other hand, everybody was full of sympathy and compassion for Lázaro, Shears’ victim: an old vaquero who could no longer rope or keep up with the cattle, though he could still play the violin beautifully—they’d invited him to play at baptisms but he refused to cross the river. He’d been around forever—grew up in Matasánchez till he was taken north while still just a child, violin in hand, not knowing how to rope cattle; they said that his aunt sold him to the Escandón family, ranchers who gave him to their cousins. Later, Doña Estefanía would brag about how well the boy roped cattle and how he could sing and play, too.

Jones, a runaway slave, is leaning against the (so-called) cathedral portico, frightened by the news he overheard while selling candles and soaps from his basket. He leaves his spot and goes from house to house with his soaps and the gossip, heading toward the Franciscan monastery, always adding something along the lines of, “Like it or not, that’s how they are; they don’t know what respect is,” in his excellent, newly learned Spanish.

He knocks on the Carranzas’ door to offer his wares and deliver the news, which causes quite a commotion. The boy of the house, Felipillo Holandés—whom the Carranzas adopted not knowing he’s a Karankawa—is overcome by a dark melancholy that he cannot explain to anyone; it’s like he’s lost the ground beneath his feet.

Then Jones delivers the news to the house next door, where Nepomuceno is practically a god. “Don’t let Laura hear!” But Laura, only a few months older than Felipillo Holandés, has already heard. Angry tears begin to pour from her eyes: how could someone dare insult her hero, her savior, the man who rescued her from captivity?!

Don Marcelino, who rises at dawn every day of the week, including Sundays, to search for plant specimens for his herbarium (“that crazy old plant man,” as the old women and children call him) is returning to Matasánchez from a two week expedition when he hears the news. It’s only half-translated and the “Shut up” part’s been run together. He immediately takes a piece of paper from his shirt pocket and writes with a sharp-tipped pencil, “shorup: used to order someone to be quiet. A scornful command.” He thinks it’s a Spanish word. He collects words the same way he collects plants.

Later Don Marcelino folds the paper and puts it away next to his pencil, careful to put the tip up so it doesn’t become dulled. He goes inside his house. He removes his boots just past the front door and doesn’t give the subject another thought.

Petronila, a vaquero’s daughter—she was conceived on Rancho Petronila, hence her name—is standing on her balcony when she hears the news. She goes inside, puts on a shawl, (although it’s hot outside, that’s what decent women do, otherwise her neck would be exposed; at home she leaves her head uncovered) and goes out shouting to her friends, “The Robin brothers are coming!”

The legend of these handsome bandits has been passed from señorita to señorita. The brothers are the Devil incarnate: the most terrible threat, and the most hoped-for.

In the street, Jones sees his friend Roberto, one of the Negroes who escaped when Texan landowners fled to Louisiana before the battle of San Jacinto (they dropped everything and ran for their lives, absolutely terrified, shouting “The Mexicans are coming!” The slaves took advantage of the chaos, “Let’s scram!”, and escaped).

“Roberto, come here! I have to tell you something …”

No sooner does he hear what Shears said than poor Roberto breaks out into hives. The Mexicans had welcomed him with open arms. But now the gringos are getting bolder, perhaps they will cross the Río Bravo to capture fugitives? It had already happened once before, when the mayor locked some escaped slaves in the town jail to protect them, but now things aren’t the same because Nepomuceno and the mayor have their differences, and no one is going to come to their rescue. Ouch, his hives! His skin is covered in tiny red bumps. He begins to scratch and can’t stop.

At the arcades, while having his shoes shined, Doctor Velafuente tells the bootblack, Pepe; then he tells the tobacconist when he stops in to pay for his snuff; at the post office he announces the news loudly to Domingo, who seals the letter the Doctor sends to his sister Lolita every week; and on Hidalgo Street he repeats it to Gómez, the mayor’s assistant, whom he runs into when he’s deciding whether to follow his routine and go to the café, or go to the barber (where Goyo recently cut his hair), or even go home (but it’s too early, the news is really messing up his daily routine). All he really wants to do is get on board the White Lily (the one luxury in his life, his fishing boat), but “that would be irresponsible.”

Gómez, the mayor’s assistant, has no sooner heard Doctor Velafuente’s news than he wants to go directly to tell his boss, but first he must hurry to deliver a “personal and confidential” message for Matasánchez’s new jailkeeper.

He delivers the message and the news about Shears’ phrase as well. It’s received quite differently than it was in Bruneville’s jail. Here there’s only one prisoner, not a prize catch, like Urrutia on the other side of the river; however, in the presidio on the outskirts of Matasánchez, there are scores of prisoners, among whom there are at least a half-dozen big fish.

This solitary prisoner is from the north. He’s a Comanche called Green Horn. Captain Randolph B. Marcy (one of the good gringos) brought him in and accused him of torturing a Negro girl named Pepementia, who is no longer a slave under Mexican law.

Captain Marcy recognized Green Horn in Matasánchez one day, seized him on the spot, and took him directly to the authorities.

In his defense, Green Horn said in perfect Spanish (he speaks several languages): “We did it solely out of scientific interest. We wanted to see if they’re as black on the inside as they are on the outside; that’s why we were peeling back and scrutinizing her layers of skin and muscles.”

Gutiérrez, a lawyer known for his guile and his profitable connections in the Comanche slave trade, is defending Green Horn.

It would have been impossible for Captain Marcy to bring charges in Bruneville, or any other city in American territory, but in Mexico he knew the authorities would take it to heart.

Green Horn is being kept in the jail at the center of town because the presidio—from which it’s impossible to escape—is on the outskirts and vulnerable to Comanche raids.

When Green Horn hears the news of the Shears-Nepomuceno affair, he thinks that the gringos will ride into Matasánchez in reprisal and liberate him from “these disgusting meals and salsas, these flatulent greasers.” He has to restrain himself from breaking into song.

The jailkeeper—who doesn’t have an official title—is a friend of Carvajal, Nepomuceno’s political rival; he has many reasons to rejoice:

1 At last he has something to distract him from his boredom.

2 The position he’s been given by the mayor is humiliating—he’s no more than a security guard, a lowly post unbecoming to a man of his lineage, but he needs the money. “If I’d bought land to the north of the river when the time was right, I’d be set for life” (which, given the gringo takeover, is not true).

3 He thinks he’s finally got his shot at glory; he’s always been on the sidelines when things happen, but not this time, he’s in the jailhouse and something big’s going to happen here.

The jailkeeper caresses the pistols in his holsters.

No one remembers his name.

His duty done, Gómez, the mayor’s assistant, returns to the office. He arrives to find his boss, Don José María, whose famous family’s surname has been popularly replaced by “de la Cerva y Tana” (meaning “blow gun”, a nickname that mocks his inability to open his mouth without spitting verbal bullets at people), carrying an envelope bearing the central government’s seal. Upon hearing the news about Shears the mayor tears the letter open and tosses it onto his desk, unread, and begins to rant and rave as usual, while folding the envelope over and over again, as though it were the envelope’s fault:

He curses Gómez for bearing the news.

He curses Bruneville.

He curses Shears: “Idiot, good-for-nothing, doesn’t even know how to hammer a nail.”

He curses Lázaro Rueda for being drunk: “Booze isn’t good for him, the violin, on the other hand …”

He curses up and down, left and right.

When he’s vented this string of insults he asks loudly, “And now what are we supposed to do? There’s no doubt that Nepomuceno will retaliate, and how! Where does this leave the rest of us?”

The letter lies on his desk, still unread. It’s signed by Francisco Manuel Sánchez de Tagle. It says, in large, clear letters:

I RECOMMEND THAT THE NEGRO FUGITIVES FROM THE UNITED STATES REMAIN IN THE CITIES ALONG OUR NORTHERN BORDER, AS MUCH TO PROVIDE LODGING FOR THEM WITH DIGNITY AS BEFITS ANY MEXICAN CITIZEN, AS TO PROTECT OUR COUNTRY FROM AMERICAN RAIDS.

In the courtyard of Aunt Cuca’s house, Catalino changes the message tied to another pigeon, Mi Morena, and sets her flying southward.

Mi Morena arrives in the camp of the Seminoles (or Mascogos, as the Mexicans call them). The message is handed immediately to Wild Horse, the chief, and to Juan Caballo, the leader of the fugitive African slaves, an ally of Wild Horse from long before their sojourn south of the Río Bravo.

The message makes the Seminoles anxious. It reawakens their worst fear: the frontier may no longer provide protection against the gringos.

“We left everything we knew,” says Wild Horse, “to escape from the White Cholera. We bade goodbye to the buffalo, the plains, the birds and their songs. Now we risk our lives living in caves where moss grows on our clothes, beneath an unknown sky where no ducks fly, in stagnant air that reverberates with the sounds of unknown insects, on unforgiving land, just to get away from the gringos. Have we changed our world for nothing, only to suffer them again?”

The members of the camp wail and beat their chests. In a few hours they send Mi Morena back. She returns to Matasánchez without a message.

They send their message to Querétaro, via Parcial, Juan Caballo’s pigeon, who flies off. If we were to wait for him to arrive we’d lose the thread of our story, so we’ll leave it there and go back to the Valley of the Rio Grande, the prairie, Indian Territory.

Nicolaso writes out copies of the phrase and entrusts them to several pigeons. We saw the first one fly to Matasánchez with Favorita. The second travels northward on the feet of Hidalgo, the white pigeon. On the Pulla cotton plantation a young mulatto (son of Lucie, the slave they say was mistress to Gabriel Ronsard, the café owner) receives the pigeon, scratches his crotch, and reads the message aloud. The overseer scratches his head and listens. The Negros under his supervision listen, too, scratching their chests and necks in front of a small group of Indians who have come to trade—they’ve brought two tame mustangs they want to exchange for bullets and cotton, which they’ll take back to Indian Territory and exchange for prisoners.

The Indians don’t itch themselves now—the Pulla plantation is infested with fleas—but they’ll be itching later, after they bring the bug-ridden cotton home with them.

For the cautious, vindictive foreman the news is of little interest, no matter how he looks at it he can’t see why it matters.

For the Negros it’s downright scandalous. Nepomuceno is a living legend. According to local lore he was kidnapped by Indians as a boy, an unfounded rumor that was spread by El Tigre, the runaway slave from Guinea who was captured by the Comanches and returned to his owner for a handsome reward. A good-looking, healthy, young Negro with strong teeth who could read and write, he was clean, conscientious, and hard-working, worth his weight in gold. From the day of his arrival he has told stories, many untrue, about Nepomuceno.

Having been kidnapped isn’t the only reason Nepomuceno is a living legend. It’s the stories about his riding, cattle-rustling, skirt-chasing, and fighting, along with his unparalleled roping skills and having been born into money, that make him a living legend; cowards fear him and women dream about him for good reason. There’s no one like Nepomuceno—who’s also a redhead, according to some.

The young mulatto puts Hidalgo in the pigeon loft and begins to pray: “Holy Mother, look after Don Nepomuceno.”

A third pigeon flies the first leg of his trip alongside Hidalgo. When Hidalgo lands in Pulla, the other pigeon continues across a stretch of bare land, where there’s not even one lonely huisache, just stone-hard earth, before landing on the adobe arch that guards the Well of the Fallen.

That’s how Noah Smithwick, the Texan pioneer who leads slave-hunting parties, hears the news. These men make a fortune by returning slaves to their so-called owners for ransom. As you might imagine, Shears’ insult is a joy to Noah Smithwick’s ears. He detests Nepomuceno and anyone else who so much as resembles a Mexican. Mexico ruins his trade, with its nonsensical ideas about property and other crazy notions, which would drive any self-respecting businessman to rack and ruin.

“The Mexicans will never amount to anything, they’re a people without wherewithal, good for nothing but cooking and looking after the horses.”

Two Born-to-Run Indians carry the news northward from the Well of the Fallen.

The news quickly reaches the King Ranch, neither by pigeon nor by Born-to-Run. A godlike horseman (dressed in white, riding a white mare) delivers the news, so quickly, in fact, that it was said to have been delivered by lightning bolt.

The news travels north toward the Coal Gang with the Born-to-Run Indians.

The Coal Gang are bandits who roam both sides of the frontier; they go wherever the loot is. The majority are Mexicans. They have their preferred targets:

1 Gringos. And anyone who looks like them, with the exception of their leader, Bruno, who has the blondest beard in the region—his men say it’s because of the sun, which has bleached it, but those who knew him back when he hid beneath his mother’s dark skirts and the brim of his father’s (very elegant) hat know that he was born with white hair, and skin so white it was almost blinding. But now Bruno is dark as ebony. A miner who made his own fortune rather than inheriting one, he had silver mines in Zacatecas and a gold mine further north. Business was doing so well there that he decided to sell the silver mines to finance his prospecting, investing everything but the shirt on his back. But it was his bad luck that the Great Theft had begun, and they took his mine from him using the law. He had conquered the bowels of the earth, but he couldn’t prevail against evil.

2 Stealman’s friends. Stealman is the one who, from his office in New York, carried out the aforementioned legal proceedings.

3 The Nouveau Riche, who made their fortunes off the new frontier.

4 Priests, and especially bishops, who knows why.

Their guiding principles were clear: first their profit and their benefit. Secondly, their benefit and their profit. Thirdly, their profit and their benefit. Fourthly, their enjoyment—and that’s where things get complicated.

The Coal Gang is like a family. Their leader, Bruno, was born on an island in the distant north. Some call him The Viking, but he doesn’t look it—his father was the bastard son of the King of Sweden. The rest of the gang was born in the region, in or near the Río Bravo Valley. It’s all the same to them.

Each of them has been betrayed by his nearest and dearest: