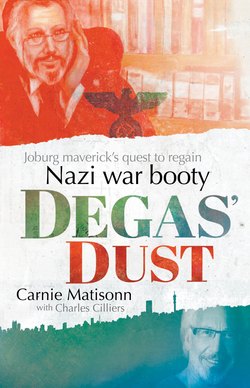

Читать книгу Degas' Dust - Carnie Matisonn - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Prologue

ОглавлениеThe Norwegian blitzkrieg

Among the millions of large and small tragedies sewn into the bloody tapestry of the worst war to befall the 20th century was the small story of my granduncle Karnielsohn. He lived and died in Oslo, Norway. It was a cold and distant world away from the temperate grasslands in Africa where I would grow up, not long after his murder.

Karnielsohn, after a life as a successful lawyer, in his greyer years became a semi-recluse who found his greatest comfort in art and literature. His collection of art was, by all accounts, something many aspiring artists came to admire. He had been happy enough to spend as much of his time as he could with people whose names and work would survive and ripple through time, thanks to their talent and brilliance. But after his retirement, he avoided contact with friends and family.

And after his city was placed in the cold grip of the Third Reich, all further opportunities for meaningful human interaction went with it.

It’s true that a moment of violence does not just tear through flesh and bone; it does not just spill ordinary, human blood … it can rend space and time and bleed into the present. Something like that happened on the Friday evening my granduncle was murdered.

But during the war, every day must have felt like that to somebody.

There were many victims in Norway following what had happened on April 8, 1940, when German forces attacked Norway by sea and air as part of the ambitious Nazi invasion plan called Operation Weserübung. The ease with which Germany was able to take control of Denmark and Norway is captured in the name of the invasion itself, which translates to “Weser exercise”, after the Weser River in Germany. Overcoming Scandinavia and its futile efforts to withstand invasion had been little more than “an exercise” for the Nazis, who knew they had far greater challenges ahead.

The major Norwegian ports from Oslo northward to Narvik were overrun and occupied by advanced detachments of German troops. A single parachute battalion took the Oslo and Stavanger airfields and 800 aircraft overwhelmed the Norwegian army. German troops from the airfield entered the city virtually unopposed, making a mockery of the country’s plan to try to defend itself using only its navy.

Germany owned the Norwegian skies, the fearsome Luftwaffe’s superiority humbling Norway’s poor fishing folk.

The country and a combination of British and French naval forces were embarrassed by an ineffective and badly managed Allied attempt to regain control in what was one of the first big lessons for the Allies: that sea power without air power was doomed. If Germany and its Luftwaffe were ever to be defeated, the Allies would have to regain their dominance of the skies.

But thoughts such as these – of taking the fight to Germany and the Axis powers – could not even be entertained in the latter months of 1940, when the tall, dark shadow of Nazism was cast over all of Europe and looked all but impossible to clear. The ageing Norwegian king, Haakon VII, after leading the fight to retain control of his country for nearly two months, fled desperately for England on the British cruiser HMS Glasgow, to a government in exile.

Germany found itself in control of the country’s prized ice-free harbours, from which Nazi ships and submarines could extend control over the North Atlantic. To Adolf Hitler, this was an important cog in a plan to compel Britain to surrender or become a grudging ally. Controlling Norway also ensured a steady supply of iron ore from mines in Sweden through the port at Narvik. And as if this were not enough, Norway’s so-called heavy water would become critical to Germany’s attempts to build an atomic bomb.

Hitler garrisoned troops numbering about 300 000 in the country for the remainder of the war. They swiftly set about establishing naval and air bases from which to attack Britain.

During this time, the Scandinavians lost all major trading partners and the Norwegians themselves were soon confronted by the daily scarcity of almost everything they needed, food most of all. Their government was led by its new minister president, Vidkun Quisling – a Norwegian whose name would live in infamy and become a dictionary entry for someone who betrays his country.

Quisling, no doubt delighted at selling the soul of his country to its occupiers, attempted daily to convince his compatriots to love the Nazis with the same fervour he did. But the presence of the Wehrmacht was terrifying, and most ordinary Norwegians did their best to stay out of the German soldiers’ way.

This went hundredfold for anyone unfortunate enough to be Jewish as Quisling’s government was participating, perhaps knowingly, in what were the beginnings of Hitler’s Final Solution.

At the beginning of the occupation, there were at least 2 173 Jews in Norway, representing a tiny sliver of the country’s population. No fewer than 775 Jews were arrested, detained and deported. Of these, 742 were murdered in concentration camps and 23 died by extrajudicial execution, murder and suicide, bringing the total number of those killed to 765. At least 230 households were wiped out.

My granduncle was one of those 765.

That final Friday evening in February of 1941 started quietly for him, like any other winter twilight in Oslo, where the sun was by nature little more than a thin orange line on the horizon by mid-afternoon and where night and its chills came early.

The streets of Oslo were covered in snow. The rooftops of the houses in Karnielsohn’s modest neighbourhood were an undulating sea of white snowflakes gathering beneath a black, starless sky. The peaceful scene belied the truth of soldiers’ boot prints being hammered into the snow every day. Nazi storm troopers had already been in the city for ten months.

There was a pounding on Karnielsohn’s apartment door. Before he could dislodge the latch, the hinges on his door relented as the soldiers kicked it down. They had seen a Mezuzah parchment in the shape of a scroll, dutifully affixed to the entrance of his home – all they needed to confirm this was the residence of a Jew.

The officious thugs moved from room to room, ripping paintings off walls and tearing furniture apart. An SS officer drew his pistol and shouted to the others to throw Karnielsohn into the street. They jostled him out and kicked him off the veranda. He crashed down the stairs, only to endure a barrage of kicks from the Nazis’ gumboots.

It ended as abruptly as it had begun, with a single shot to Karnielsohn’s head.

In that apartment they found a portrait painted by one of my uncle’s one-time friends, the celebrated French Impressionist Edgar Degas. One of the founders of Impressionism, the artist had died aged 83 in 1917, leaving that portrait of my granduncle, painted decades earlier, as evidence that they had once known each other.

The Nazis helped themselves to that painting, as well as Karnielsohn’s other artworks – much as they did in thousands of other homes throughout war-torn Europe. That single artwork became a tantalising piece of evidence of an old crime. Its existence kept the possibility alive that its value and uniqueness would eventually lead to its recovery, along with all the other artworks in Karnielsohn’s home, and perhaps even point out the murderer who had stolen it.

That possibility appeared remote but, all the same, could not be dismissed as unachievable.

Throughout my life, many would tell me its recovery was nothing less than an exercise in futility.

But that only made me more determined to pursue the dream. It was to become my lifelong quest to recover it, along with all the other treasures that had been looted on that pitiful, snowy evening in Oslo.