Читать книгу Rude Awakenings: An American Historian's Encounter With Nazism, Communism and McCarthyism - Carol Jr. Sicherman - Страница 17

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

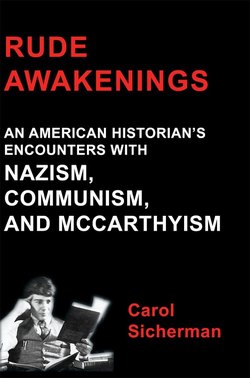

Paul Gottschalk, alias P.G.

ОглавлениеPaul Gottschalk’s family and friends felt universal “admiration and love” for him.54 To the young people in his family and his office he was a solicitous but stern mentor; they called him “P.G.,” the abbreviation summing up the half-intimate, half-formal nature of many of his personal relationships. They were “fascinated by his unique and glamorous business”–visits to America were a rarity at the time–and appreciated him as “a cultured and friendly person with many stories about his friends and contacts on both continents.”55 With Paul as the generous host, the family gathered annually to celebrate his birthday; twenty guests attended his fifty-third, in 1933. Harry was grateful for P.G.’s self-assigned role as “guide and confessor.”56 Perhaps Paul recognized a kindred spirit, for as a youth he too had been so shy outside his family that he appeared to be “stupid or mute.”57 Harry could pop in to P.G.’s office at 3a Unter den Linden, just down the street from the university, and get advice or cash, pick up a book, or discuss politics.58

At the end of Paul’s very long life, he was persuaded to write his memoirs.59 He began with a reminiscence of his mother, from whom he “inherited a capacity for vivid fantasy, a quick wit, and perhaps also a great interest in people and their concerns, and if I may say so, the natural gift for gaining the confidence and winning the friendship of people.” This gift was apparent in his relations with librarians and collectors, which were at once professional and social. His formal education ended in 1899, when he passed the Abitur. With a scholarly bent, he chose the antiquarian trade over academia because of the greater chance of success, for most Jewish academics were relegated to the lower ranks.60 For the most part, he acquired on his own the “all-encompassing knowledge” that he thought essential for his chosen profession.61 He was “at heart a pedagogue, with a need to teach all the bright, young, loyal workers he had the knack of finding.”62 In his New York office, even a part-time packer had to read French and German–“somewhat unusual requirements,” recalled Arthur H. Minters, an assistant who became an antiquarian book dealer himself. P.G. lectured his assistants “about the book trade in Europe before both world wars”; subjecting them to a monthly quiz, “he would scold us or box our ears if we answered stupidly. ‘A grown-up must do it!’ he’d say if we called on him for help.” One of his daily habits was looking in the New York Times obits for recently dead collectors whose heirs might be eager to sell.63

During the self-designed study tour to Italy in 1906 that launched his career, P.G. visited museums, libraries, antiquarians, and private collectors. Although only twenty-six, he so enchanted the specialists with whom he talked that they gave him good deals. In Rome the advice of an antiquarian to do business in the United States “struck me like lightening and was decisive for my business and for my life.” On his first American trip later that year, he made cold calls on custodians of major research libraries, persuading them that he could find the rare and out-of-print books that they had hitherto sought in vain. He could, and he did. Beginning in 1907, he issued catalogues listing incunabula and other rare books, runs of European scientific journals, and unpublished manuscripts ranging from holograph scores by famous European composers to Americana by such figures as Franklin and Washington.64 Copiously illustrated, accompanied by scholarly texts, and published privately in limited editions, these catalogues are now themselves antiquarian items. He was well connected throughout Europe. When the philosopher Karl Jaspers traveled in Italy in 1922, P.G.– who knew him through Gustav Mayer, Jaspers’s brother-in-law– arranged for him to meet with the famous philosopher Benedetto Croce.65 He also introduced Harry to Jaspers in Heidelberg. “Too naive to talk to one of Germany’s two leading philosophers,” Harry at least retained “a sort of photo image in my mind.”66

Although P.G.’s life was affected by wars, economic downturns, and the like, his talent for making the best of things gave him success or serenity (and, at times, both). When World War I broke out, three American university libraries asked him to collect war-related materials, which he did even after being drafted; at the end of the war, he sent them collections of historical importance.67 He had no qualifications whatsoever for soldiering. His poor eyesight relegated him first to chopping wood and digging ditches; a 1915 photograph shows him looking incongruously plebeian in his uniform as a Schipper–a man who uses a shovel.68 The authorities soon made better use of his gifts, which included facility in languages; he liked to say that he spoke five languages “fliessend und falsch” (fluently and incorrectly). His military supervisor had him censor correspondence and foreign-language printed matter and later assigned him to appraise an Air Force library.69 Reading German newspapers aloud to his fellow shovelers “gave me an excellent opportunity of becoming acquainted with the psychology of classes with which I had rarely come into contact.” As Harry was later to do, he learned from the foreign newspapers what was being suppressed in the German press.

After World War I, P.G.’s astute decision to conduct business only in dollars shielded him from the economic afflictions of the 1920s, including the disastrous German crash in 1923, and enabled him to buy important collections from destitute collectors. Obtaining a visa to the United States right after World War I was extremely difficult, but not for him: a friend in Washington helped. Because the two countries were still technically at war, American reporters sought him for interviews that, when published, contained “almost nothing I had said!” His business was not seriously depleted by the Depression; friends and relatives continued to invest in it, confident that his reliance on dollars would be protective.70 World War II badly affected his pocketbook, but not his spirit (see Chapter 5).