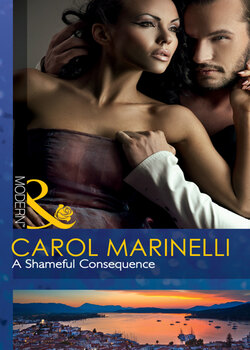

Читать книгу A Shameful Consequence - Carol Marinelli - Страница 8

CHAPTER ONE

ОглавлениеPERHAPS he should have rung.

As the car swept into the drive of his parents’ home, Nico Eliades questioned what he was even doing here—but a business deal in Athens had been closed earlier than expected, the hotel he had been intending to purchase was now his, and with a rare weekend free he had decided, given he was so close, to do his duty and fly to Lathira and visit his parents.

T did not feel like home.

Only duty led him up the steps.

Guilt even.

Because he did not like them. Did not like the way his parents used their wealth, and the way their egos required constant massage. His father had come from the mainland when Nico was one and had purchased two luxury boats that now cruised the Greek islands. No doubt, today, there would be another argument, another demand that he return to live here and invest some of his very considerable fortune in the family business. Another teary plea from his mother, to find a bride and give them grandchildren—that he should thank them for all they had done.

Thank them?

For what?

Nico blew out a breath because he did not want to go in there hostile, truly did not want another row, but always they threw in that line, always they told him he should be more grateful—for the schooling, for the clothing, for the chances.

For doing what any parent would surely do, could they afford it, for their son.

‘They are not here.’ The maid looked worried, for his parents would be angry they had missed a rare visit from Nico. ‘They are at the wedding, they don’t return till tomorrow.’

‘Ah, the wedding.’ Nico had forgotten. He had told his parents he would not be attending and for once they had not argued. It was the wedding of Stavros, the son of Dimitri, his father’s main business rival. Normally at events such as these, his fat her insisted Nico attend be cause he wanted to parade his more successful son.

Nico’s ego did not need it.

But, surprisingly, his parents had not pressed him to attend on this occasion.

Now here he was, reluctant to leave without having at least seen them—it had been weeks, no, months since he had been back, and if he saw them now then it could be several months more before he had to visit again.

‘Where?’ Nico asked the maid. ‘Where is the wedding?’

Because Charlotte, his PA, had told him of the invitation, just not of the details.

‘Xanos.’ The maid said and screwed up her nose slightly as she did so, because even though Xanos had recently become the most exclusive retreat for the rich and famous, the locals were poor and the people of Lathira considered themselves superior. ‘That is where the bride is from so they must marry there.’

‘In the south?’ Nico asked, because that would mean Stavros had done well for himself. But the maid gave a small smile as she answered.

‘No, in the old town—your father and Dimitri have to rough it tonight.’

And now Nico did smile, for though his father was certainly wealthy, the south with its luxury resorts and exclusive access was way beyond his father’s reach.

He would go, Nico decided.

He did not care that he had declined, details like that did not concern him. Staff moved mountains, tables appeared, presidential suites were conjured up wherever he landed—Charlotte would sort it out.

Except she, too, was at a wedding today in London, he remembered.

‘Sort out my clothes,’ he told the maid, as his driver brought up his cases and Nico told him to arrange the transport.

‘The transport is all taken.’ The driver was nervous to inform him. ‘The helicopters took all the family last night, they don’t return till tomorrow.’

‘No problem.’ Dressed and ready, he ordered the driver to the ferry. He was used to different drivers: Nico did not really have a base. What he was not used to was attending to small details for himself, but his PA was usually available night and day and she did deserve this one weekend off.

He did not care for the stares of his fellow passengers as he paid for his ticket.

Dressed in a dark suit, he sat amongst tourists who gaped at the beautiful man in dark glasses, who did not belong on the local ferry.

Public transport was not so bad, Nico decided, buying a strong coffee, intending to read the paper to pass the time, but there was a baby crying behind him and it would not stop.

He tried to concentrate on the paper, but the baby’s screams grew louder; there was a discomfort that spread through him, a growing unease as the ferry dipped and rose, the fumes reaching his nostrils. Still the baby sobbed. He turned and saw the mother clutching it, and Nico’s expression was so severe the mother quailed.

‘Sorry,’ she said, trying to hush her child.

He shook his head, tried to tell the woman that he was not angry, but his throat was suddenly dry. He stared at the water and the island of Xanos ahead of him, felt the wind on his face and heard the screams of the baby. Despite the warm afternoon sun, a chill spread through Nico, and he felt a sweat break out on his face and for a moment thought he might vomit.

He stood, his legs for the first time unsteady, and he moved to the rail of the ferry and made himself walk away from the passengers. He was too proud to appear weak even in front of strangers, but still the baby’s screams reached him.

Perhaps he was seasick, Nico told himself, dragging in air that did not soothe because it tasted of salt. But he could not be, for he sailed regularly. Weekends were often spent on his yacht—no, Nico knew this was something different.

Still the baby screamed and he looked towards Lathira, from where he had set off and then over to Xanos, where he was headed, and the foreboding did not leave him.

They docked and he walked briskly from the boat—decided he was not going to get used to public transport, that a helicopter would fly him back. Nico walked to a taxi and asked to be taken to the town church. He stared out of the window and did not respond to the driver’s attempts at conversation, just stared out at streets that were somehow familiar. As they arrived at the church, he recognised it and could not fathom why, did not want to. Even climbing the steps, somehow he felt as if he were recalling a dream and Nico stood for a moment to steady himself before going in.

The bride was arriving and he watched as she stepped out of the car and a swarm of bridesmaids, like coloured butterflies, busily worked around her, brushing down her dress. The older one fiddled with the simple veil that would soon be lifted over the bride’s face before entering the church. Nico realised, whether she was from the north or the south, Stavros had done incredibly well for himself for she was quite simply stunning. How wasted she would be on the groom.

Was it the dress? Nico mused as he watched her. It was simple and straight, yet it nipped in at the waist to show her voluptuous curves. Or perhaps it was the heavy, full breasts that were so absent on the rakethin women he usually dated that were the allure. He was used to sculpted, exercised, false curves—yet this bride’s body was lush. Her breasts moved as she lowered her head to thank her small flower girl, in a way the breasts he was used to holding never did—they were flesh, Nico knew, as was the curve of her bottom. There was a softness to her stomach that was natural. Her skin was creamy and pale for a local, and he could not take his eyes from her, felt the disquiet that had plagued him since he’d stepped onto the ferry subside as he quietly observed.

Her thick dark hair was worn up and how Nico would have liked to take it down. He could not make out the colour of her eyes from this distance but they glittered and smiled as she laughed at something that her bridesmaid said—and it was her energy that was stunning, the smile and the laughter and the way she took her father’s arm. Then he saw her still as the priest walked towards her, saw her tense for a brief moment and straighten her shoulders, saw the swallow in her throat and the smile slip from her face as everyone moved to their positions. It was more than nerves, Nico thought as she closed her eyes for a long few seconds. It was as if she was bracing herself to go in, but then her lovely face disappeared from view as the bridesmaid arranged the veil.

It was normal to be nervous, Connie told herself as the priest walked towards her, but suddenly it was real. The preparation for this day had been all-consuming, her father determined that his only child would have a wedding fit for this prominent family. He would show the people of Xanos and his friends in Lathira that, despite rumours to the contrary, he was doing well. For weeks, or rather months, Connie had been swept along on a tide of dress fittings, menu selections, dance lessons with Stavros, but only now as she stood behind her veil with the priest telling her it was time did it seem real.

This was her life: this was happening whether she wanted it or not.

No one knew of her private tears when her father had told her of the husband that had been chosen for her. And later, when she had confided in her mother that Stavros’s words were cruel at times, her mother had told her to be quiet. Even when, awkward and embarrassed, she’d told her mother that he did not seem interested in her, that he had not so much as tried to kiss her, her mother had told her they had chosen a gentleman for her. That sort of thing was for when she was safely his.

A bride, Connie told herself as she sucked in air, was supposed to be nervous on her wedding day.

And a bride was supposed to be nervous about her wedding night.

Was she the last virgin bride?

The boys and, later, men of the island had been too nervous of her protective father to date her. How she’d yearned for fun and laughter … and, yes, romance, too.

But there had been none.

Even during her business studies in Athens, which she’d loved, she’d been guarded by her cousin; every move she’d made had been reported back to her family, till she had returned to the island and commenced work in her father’s small firm.

As was expected.

‘Kalí tíhi.’ Her bridesmaid wished her luck and Connie closed her eyes as her father took her arm. He felt so frail Constantine wondered who was holding who up.

This was why she was here, Constantine reminded herself.

Her father’s dearest wish, to see his daughter safely married.

It wasn’t at all unusual on the island for the family to choose the partner. In fact, it was how things were done here. There was no question that she would disobey. Already she had put off this day for her studies. And she was … fond of Stavros, Connie told herself, even if his words were sometimes harsh. Love would grow, her mother had told her. They had chosen well for their daughter, she had been assured.

Yet there was a stab of grief as the priest commenced chanting, as the bridesmaid covered her face with the veil and the procession moved towards the church, grief for all she would now never know.

She was naive only in body. Of course she knew there were other ways for couples to meet—she had heard of them, read of them, gossiped about them with her more worldly friends during her studies. She had listened to their tales of flirting and fun, dates and romance, first kisses and reckless nights, break-ups and tears, and she wanted to sample each and every one of those things, but it was not to be.

And then she saw him and her heart stilled.

Like an omen.

Like a black crow on the steps he stood as if warning her not to go in.

Like the devil, dark eyes beckoned; and the sun was too hot on the top of her head. It was certainly her father holding her up now, because with one look at this man she was almost dizzy. Only one long look and it was as if she tasted for a second all that had been denied, all that would be denied if she climbed the steps.

He was surely the most beautiful man she had ever seen.

Tall, he lounged against a column, shamelessly staring, which, Connie told herself, people did to a bride.

But it was how he looked that had her stomach fold over itself. It was a different sort of look from any she had experienced.

His eyes roamed over her, and she felt her body burn.

Thank God for the veil, for beneath it she burnt red, her breathing tight in her chest; she could feel the prickly heat from her face spreading across her chest and down to her arms.

Brides blushed on their wedding day, Connie told herself as she slowly climbed the steps.

Except the burn in her body was not for the man who waited at the altar, or for guests whose heads would turn when she entered. Instead, the burning was for him. It was surreal, just bizarre, to be walking towards her future, and to see at that second a different route. And as his full mouth did not move into a smile, as his eyes compelled her, so strong was the pull, so fierce the attraction, so palpable the energy between them, she was sure, quite sure, that had she walked over to him, had she run to him as her body was telling her to, that his arms would be waiting; that now, right now, she could walk away, run away, and live a life that was hers.

‘I can’t.’ Once past him she faltered at the door of the church, the smell of incense from the priest’s burner making her feel sick. ‘I can’t do this.’

‘It’s nerves,’ her father said kindly. ‘Today—’ her father’s voice came from a distance ‘—is my proudest day …’ Like waking from a dream, she was back in reality, and instead of looking backward to where his eyes still burnt on her bare shoulder, she looked forward, looked down the long aisle and saw her husband-to-be waiting.

Nico had seen her blush, had felt her start and wondered, too, what had just happened. It had felt, for a moment, as if they knew each other, as if their minds were speaking, the connection had been so strong, yet it had come from nowhere.

Perhaps they had once been lovers, Nico mused, which would explain the blush that crept down her chest and dappled her creamy arms.

He should remember, though, Nico thought, and not out of guilt, for he had held so many women in his arms that recall was often hard. Too many times an ex-lover had galloped over to him then left in tears, because the night she had treasured for so long didn’t even merit a fond memory for Nico. But as for this bride—her body, that gorgeous round face and full ripe lips—surely he would have remembered making love to a woman like that.

He made his way into the church and chose to sit quietly at the back rather than join his parents, for the bride had reached her soon-to-be husband. He noted the lack of response from Stavros: there was no smile of appreciation; no eyes that looked in wonder. Nico thought, Had she been his … And then he stopped that thought process with a wry smile, for Nico did not believe in love, could not imagine spending his life with only one other. His relationships were short-lived at best, a night most times.

Her name was Constantine, he heard from the priest, and it suited her, Nico thought.

He’d forgotten how long Greek weddings took—he stood and sat on demand during the service of the betrothal and he toyed with just slipping away unnoticed and heading for a bar before the crowning. The priest blessed the rings and asked Constantine if she was willing. Nico saw the candle she was holding flicker in her shaking hands, and truly he wanted to walk over and blow it out. He could feel her dangerous hesitation and willed her to listen to it.

For he knew she was more than this.

More than the stifling laws and traditions he had walked away from.

A place where appearance was everything, where there could be no debate, no expansion, no change.

Connie wondered, as she had wondered so many times, if there was more than this, heard the priest repeat the question, ask if she was willing, and again she wanted to run. Wanted to turn her head to the congregation, to see if those eyes would be waiting, and told herself she was being ridiculous.

This was the day she had been raised for; this was how her life was to be. Who was she to question her father, the traditions she had been born to? Finally she nodded, mumbled that she was willing, and almost heard the door close on all her secret dreams.

It did close, for on hearing that Nico moved from his pew and walked out of the church.

He went to a taverna that was waiting and ordered strong coffee and then thanked the bartender when he brought out an ouzo, too. Normally he did not drink it, it was too sickly and sweet for him, but the taste of anise on his lips and the burn as it hit his stomach had Nico order another. He stared out at a town that was somehow familiar—the dusty busy streets and colourful market, the bustle and chatter as a crowd of locals started to gather outside the church, waiting for the couple to appear. Nico pulled out his phone, was about to tell Charlotte to book him a suite on the south of the island—he would say hello to his parents and then get out—but it wasn’t out of consideration to his PA that he put away his phone. Instead, he wanted to be here, Nico realised, wanted to sit in the café in the town square and soak in the afternoon sun. He liked the scent from the taverna and the variance in dialect here on Xanos that hummed in the background. As the newly wed couple appeared on the steps, Nico walked to the hotel and informed them of his arrival, saw the nervous swallow from the concierge, because certainly this man would expect the best.

‘I will be joining the wedding,’ Nico also informed him. ‘Nico Eliades. I will sit with my parents.’ He did not ask whether that could be arranged, neither did he apologise. Nico expected and always got a yes.

‘Nico!’ His mother seemed shocked to see him as he joined them at the table. ‘Why are you here?’

‘Some greeting,’ Nico said. ‘Normally you plead with me to attend these sort of functions.’

‘Of course …’ She gave a nervous smile, her eyes desperately searching the room for her husband who, seeing Nico, strode over immediately.

‘This is a pleasant surprise.’

‘Really?’ Nico said, because his father’s eyes said otherwise. ‘You don’t seem to pleased to see me.’

‘It’s not the sort of thing you are used to.’ His mother said. ‘The hotel is shabby …’ His mother was an unbearable snob. It was a gorgeous old hotel and far from shabby. It had character and charm, two things, in his parents, that were lacking. ‘Dimitri is mortified to hold the reception here. The sooner they get this girl back to Lathira where we can have a proper celebration, the happier we will all be. Really, Nico.’ She gave him a saccharine smile. ‘This place is not for you.’

‘Well, I’m here now.’ Nico shrugged, his words dripping with sarcasm when they came. ‘What could be nicer than spending a day with my family?’

He ate, and sat bored through the speeches, deciding it had been foolish to come.

Women flirted.

Beautiful, gorgeous women. One in particular was to his usual taste and how easy it would be to take a bottle of champagne from a table, take her by the hand and go up to his room. Yet he glanced at Constantine as she danced with her husband, and silently felt regret, for she had spoilt his appetite for silicone tonight. All Nico could think was, Lucky Stavros.

It was the first time he had felt even a hint of envy toward Stavros.

The son of his father’s business rival and competitive friend, always the children had been compared.

Always Nico had won.

Except on duty.

Nico had not gone into the family business—he had chosen to go alone. At eighteen, to the protests of his family, he had headed for the mainland, worked as a junior in banking and then, when still that had not satisfied, he’d headed to America. He had faked a better résumé, and how impressed they had been with the young Greek man who could read the stockmarket. How painstaking building his own portfolio had first been, but then, with passion and determination, he had scanned global markets, invested in properties when prices had crashed, sold them when the pendulum swung back.

It always did.

How easily Nico saw that. Could not understand how others could not, for they sweated and panicked and sometimes jumped, where Nico sat calm, watching and waiting for new growth in the fertile ashes.

Each visit back home he returned richer and, despite the fights in private, his father was proud that always his son was better.

It would, though, Nico decided, be hard to match the rare beauty of Stavros’s bride.

Poor thing.

The thought jumped uninvited to the forefront of his mind as he watched her dance, not with her husband but to the tune of tradition. He watched her vie for her husband’s attention, but he was too busy talking with his koumbaros, irritated when she tapped him on the shoulder and told him they must now dance. He watched as Stavros ran his hand down her bottom and then said something into her ear.

And then he saw her pull away.

A flash of hurt, anger perhaps, in her eyes and Nico knew it had not been a compliment that had come from Stavros’s lips.

He was sure, because that was the way on Lathira, as Constantine would soon find out, that even on her wedding night she had been criticised.

It was death by a thousand cuts, the world she had entered, and he had just witnessed the first.

She would be part of Lathira’s social set—have lunch with the other trophy wives and then back to the gym the following morning to pay for it. They would seep the life from her till she was as polished and as hard as the rest, and Nico did not want to sit and witness even a moment of it. It had been a mistake to come. Nico did not do sentiment, did not enjoy weddings. All they did was cause a vague bewilderment—to share your life, your future, to entrust yourself to another?

He looked at the bride, who was not blushing but pale and visibly stressed, at his parents, who sat tense, at the couples that forced smiles and conversation, and he searched for something that might discount his theory that love did not exist. He looked around the room and there were two boys, raiding the table, laughing as they ordered cola from the waiters. Two brothers causing mischief, and he felt a twist in his soul that came from nowhere he could place.

‘I’m going to retire.’ He waited for the protest from his parents but the only protest he got was from the blonde whose name he couldn’t for the life of him remember.

‘Will we see you in the morning?’

‘Perhaps.’ Nico shrugged. ‘Or I may leave early.’

‘Come and see us on Lathira soon,’ his mother said. ‘It has been ages.’

‘I’m here now,’ Nico pointed out, because this visit had to count as one, for he would not be back for months now.

He wished he loved them.

As he walked out of the ballroom, Nico wished he was blind to their faults, but all he saw were greedy, ego-driven people.

He collected his room keys, was advised that his things were in his room, but instead of heading up there on a whim he turned and headed out to the streets.

Past the church and the taverna, along the road to the fishing boats and the fishermen who sat smoking and drinking on the beach. He followed a path that should not be familiar except he seemed to know where it led, and he walked, somehow at ease with the seamier side of town, past the late-night bars to the street that forked into cobbled alleys. He could hear breathing behind him and heavy footsteps but Nico felt no fear.

He saw the tired face of a hooker and the voice of a man behind him.

‘How much?’

He saw her face shutter as she named her price and Nico felt his heart still.

He looked down the alley to where she would take the man and he heard the words repeat in his head.

How much?

He felt dread, for the first time he felt dread and broke the conversation.

‘She’s already booked.’ He turned to the bloated, greedy face and told him she was taken. All he did was shrug and move on.

‘Since when?’ The hooker sneered.

He did not want her, but he didn’t want that man for her, either.

‘Go home,’ Nico said, and she swore at him in Greek, told him she was sick of do-gooders. Then her tirade stopped as he paid her plenty.

‘What are you paying me for?’

‘For peace,’ Nico said, even if he did not understand his own response. He just wanted to stop the trade, to wipe out one injustice.

He walked the streets; he ran through the streets like a madman; the town clock chimed and he realised it was two a.m. He wanted away from this place and how it made him feel. He would be gone first thing in the morning, would go now to his room and order their best bottle of brandy, not the sickly ouzo that churned in his stomach still.

He walked briskly through the hotel foyer, bypassed the lift and took the stairs, two, three at a time, and when nothing could have halted him, something did.

A bride still in her dress, a half-drunk bottle in one hand, a crumpled heap on the stairs, crying.

‘Leave me,’ she sobbed, and he wanted to, did not want to sit on the stairs and ask her what was wrong, for he already knew.

Did not want to sit and tell her to hush, to dry her tears and to tell her to go back there, as his father would expect him to.

He did neither.

He took her by the hand and made her stand.

Felt her hot hand in his and he wanted all of her, wanted to hold her, to stop the tears, to comfort her.

‘Leave me,’ she begged. ‘I’ll be okay in a moment.’

She wouldn’t be, Nico knew that. The champagne might dim her pain enough to send her back, but no doubt she’d need it again tomorrow, and another night and another … to get through the hell that would be her marriage, because Nico knew the truth.

‘Come with me.’ He took her by the hand and he led her.

‘Come with me to my room.’