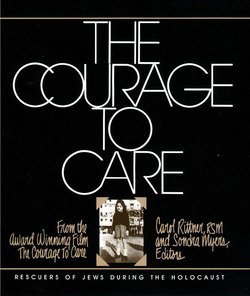

Читать книгу The Courage to Care - Carol Rittner - Страница 13

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

JOHTJE VOS

ОглавлениеI was brought up in a very strict Christian home. When my two sisters and I did something wrong, we were severely punished. When we did something right, we didn’t hear a word about it, because doing right was considered a normal thing. That’s why we still don’t think what we did in the war was a big deal. We don’t like to be called heroes. Even the words “Righteous Gentile” rub me a bit the wrong way. To be honest, I don’t feel very “righteous” and I don’t feel very “gentile.”

NETHERLANDS

I want to reflect a moment on the various attitudes that people have in the world, because it is a factor that we must consider when we talk about helping Jews during the Nazi occupation of Holland. There were people, Jewish and non-Jewish, who helped, and there were others who did not help. Similarly, there were Jews who wanted to be helped, and there were others who did not want to be helped, who preferred to carry the burden that was put upon them. It is important to keep this in mind.

In Holland before the war, at least in my experience, there was no anti-Semitism. Children were brought up with tolerance and respect for others. Certainly, in my family and my husband’s family, we learned that saying something unkind about somebody who had another race, color, creed, nationality, or whatever, was very wrong and disrespectful. And so it came very naturally to us to consider Jews just like us. We thought of them as human beings, just as we were. It was just as simple as that.

Two questions are always asked of us. One is, Why did we help Jews during the war, and the other is, Would we do it again? Now, to the last question, I have a very easy answer. I don’t know. I still work ardently for whatever I believe is right. I am on the steering committee of the Catskill Alliance for Peace. I work for Meals on Wheels. I work to help the people of El Salvador. Whatever we think is right, my husband and I work for and tiy to help. But nowadays, I don’t have to risk my life as we did in that time. So it depends on circumstances. Why did we do it then?

Well, my husband and I never sat down and discussed it or said, “Lets go help some Jews.” It happened. It was a spontaneous reaction, actually. Such things, such responses depend on fate, on the result of your upbringing, your character, on your general love for people, and most of all, on your love for God. And, I would say, there was also a kind of nonchalance and optimism about it. I would say to myself, “Oh, come on, you can do that.”

It also helped very much to have a happy marriage, because when you feel strong at home, you can be strong for other people. A lot of people did not have these advantages. I ask myself whether I can blame the people who said, “No, I can’t do it.” Some of those people lived in very unhappy homes where they quarreled all the time and didn’t trust each other.

Aart and Johtje Vos (man pointing and woman to his left), their four children. The dark-haired girl is Moana Hilfman and the man to the far left, Kurt Delmonte, both of whom they hid during the war.

People also knew that when they helped others, they would endanger the people with whom they lived, as well as the people they were hiding. Some had family members who were very sick and needed help. Some people were in a location where it was absolutely dangerous, say, next door to “quislings,” Dutch Nazis. If you were to know the circumstances of all the people who did not help, you might be thankful that some of them didn’t get involved. Some believed that it would end in disaster and failure for them, as well as for the people who were hiding. These people lacked self-confidence which, in many instances, blocked their ability to help.

We had a civil occupation (it was not very civilized, but it was civil), and other countries had a military occupation. The military people were not always very much in favor of Hitler or even against the Jews. Some of them just served in the army because they had been drafted and had to serve as soldiers. The people who occupied Holland, however—in the government—were all Nazi people—all believers in what Hitler was doing, and therefore, they were much more fanatic and much more dangerous. That’s why a lot of Dutch people could not do what so many Danes did.

A hole they dug in their garden for protection in air raids. Pictured here are their four children and Moana Hilfman (second from left).

Some Jewish people also had self-defeating attitudes. We once went to Amsterdam, to the ghetto, where I knew somebody, and we addressed a young man, who had a young wife and one child, “Come to us. We have several people in our house and we can fit a few more. It’s just a question of a few more mattresses in the living room. So why don’t you come to us? We will help you to get there.” We were members of the underground and could take care of their transportation. And he said, “No, I can’t do that.”

We said that we didn’t understand why, and he responded, “Because I’m a Jew. This has been imposed by God on our people, and I don’t think it’s right not to accept this burden. There must be a reason for all this. I have to accept it, and when I am caught and moved to Germany or to a camp, I will accept it without resistance.”

And I said, “Well, this is beautiful, courageous, and very high-falutin’, but how about your child? She’s three years old and she can’t judge for herself.” He said, “I have to judge for her.”

The happy ending to this story is that we got the child, finally, on the last day, about ten minutes before the family was deported. The child was taken by somebody from the underground and brought to us, and she is still like a daughter to us.

This is how it happened. After the Jews were picked up, the Nazis usually brought in electricians, because the houses were often pillaged. The electricians came in to prevent fires by switching off the electricity. One of those electricians was a Dutchman. I don’t know who he was, but he was a hero; he went in there with the Germans to switch off the electricity, it was just a job he was forced to do—and he ended up rescuing the child I mentioned.

The young Jewish couple was there with their child. At the last moment the wife said, “We cannot sacrifice our child for our principles,” and so the electrician said, “Okay, give the child to me.” The child had a broken arm, and it helped, because the electrician put her on the back of his bicycle and said to the Nazis, “I have to bring my child to the doctor.” They believed it, and he was able to bring the child to us. He dropped her in our garden and then disappeared. I still would like to find him one day and thank him.

Moana Hilfman, the little Jewish girl from Amsterdam, whom the Vos family hid during the war.

Some people have asked me whether I was ever afraid. Oh, God, yes! 1 was scared to death. And very near death also. At one point I was in the hands of the Gestapo, my husband was in jail, and the Nazis were doing a lot of house searching. We were hiding 36 people, 32 Jews, and four others who also were being sought by the Gestapo. We had made a tunnel underground from our house to a nature reservation, and when we got a warning or had an inkling that the village was surrounded, they all went in there. They all came through because we had a house in which we could do such things. It was not always easy and often we were frightened, but we were able to help a little bit, and we did it because we believed it was the right thing to do. And that is why we were able to help Jewish people during the Nazi occupation of Holland.

Johtje Vos and her husband, Aart, were involved in the underground effort in Holland to help the Jews. They now live in Woodstock, New York. Both were honored by Yad Vashem.