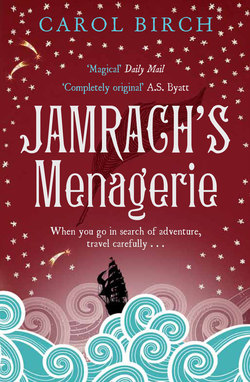

Читать книгу Jamrach's Menagerie - Carol Birch - Страница 6

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление1

I was born twice. First in a wooden room that jutted out over the black water of the Thames, and then again eight years later in the Highway, when the tiger took me in his mouth and everything truly began.

Say Bermondsey and they wrinkle their noses. Still, it was the home before all other homes. The river lapped beneath us as we slept. Our door looked out over a wooden rail into the channel at the front, where dark water heaved up an odd sullen grey bubble. If you looked down through the slats, you could see things moving in the swill below. Thick green slime, glistening in the slosh that banged up against it, crept up the crumbling wooden piles.

I remember the jagged lanes with bent elbows and crooked knees, rutted horse shit in the road, the dung of sheep that passed our house every day from the marshes and the cattle bellowing their unbearable sorrows in the tannery yard. I remember the dark bricks of the tanning factory, and the rain falling black. The wrinkled red bricks of the walls were gone all to tarry soot. If you touched them the tips of your fingers came away shiny black. A heavy smell came up from under the wooden bridge and got you in the gob as you crossed in the morning going to work.

The air over the river though was full of sound and rain. And sometimes at night the sound of sailors sang out over the winking water – voices wild and dark to me as the elements themselves – lilts from everywhere, strange tongues that lisped and shouted, melodies running up and down like many small flights of stairs, making me feel as if I was far away in those strange hot-sun places.

The river was a great thing seen from the bank, but a foul thing when your bare toes encountered the thin red worms that lived in its sticky mud. I remember them wriggling between.

But look at us.

Crawling up and down the new sewers like maggots ourselves, thin grey boys, thin grey girls, grey as the mud we walked in, splashing along the dark, round-mouthed tunnels that stank like hell. The sides were caked in crusty, black shit. Peeling out pennies and trying to fill our pockets, we wore our handkerchiefs over our noses and mouths, our eyes stang and ran. Sometimes we retched. It was something you did, like a sneeze or a belch. And when we came blinking out onto the foreshore, there we would see a vision of beauty: a great wonder, a tall and noble three-masted clipper bringing tea from India, bearing down upon the Pool of London, where a hundred ships lay resting like pure-bred horses getting groomed, renewed, readied, soothed and calmed for the great sea trial to come.

But our pockets were never full. I remember the gnawing in my belly, the hunger retch. That thing my body did nights when I lay in bed.

All of this was a long time ago. In those days my mother could easily have passed for a child. She was a small, tough thing with muscular shoulders and arms. When she walked she strode, swinging her arms from the shoulders. She was a laugh, my ma. She and I slept together in a truckle. We used to sing together getting off to sleep in that room over the river – a very pretty, cracked voice she had – but a man came sometimes, and then I had to go next door and kip in one end of a big tumbled old feather bed, with the small naked feet of very young children pushing up the blankets on either side of my head, and the fleas feasting on me.

The man that came to see my mother wasn’t my father. My father was a sailor who died before I was born, so Ma said, but she never said much. This man was a long, thin, wild-eyed streak of a thing with a mouth of crooked teeth, and deft feet that constantly tapped out rhythms as he sat. I suppose he must have had a name, but I never knew it, or if I did I’ve forgotten. It doesn’t matter. I never had anything to do with him, or he with me.

He came when she was humming over her sewing one day – some sailor’s pants gone in the crotch – threw her down upon the floor, and started kicking her and calling her a dirty whore. I was scared, more scared I think than I had ever been before. She rolled away, hitting her head against the table leg, then up she jumped, screaming blue murder, that he was a bastard and a fly boy and she’d none of him no more, flailing with her short strong arms and both fists balled for punching.

‘Liar!’ he roared.

I never knew he had a voice like that. As if he was twice as big.

‘Liar!’

‘You call me a liar?’ she screeched, and went for the sides of his head, grabbing him by both ears and bashing his head about as if it was an old cushion she was shaking up. When she let go he wobbled. She ran out onto the walkway hollering at the top of her voice, and all the neighbour women came out at a run with their skirts hoicked up, some with knives, some with sticks or pots, and one with a candlestick. He dashed out amongst them with his own knife drawn, a vicious big stabber raised over his shoulder, damning them all as whores and scattering them back as he ran for the bridge.

‘I’ll get you, you bitch!’ he yelled back. ‘I’ll get you and I’ll cut out your lights!’

That night we ran away. Or that’s how I remember it. Possibly it was not that night, possibly it was a few days or a week later, but I remember no more of Bermondsey after that, only the brightness of the moon on the river as I followed my mother barefoot over London Bridge, to my second birth. I was eight years old.

I know we came in time to the streets about Ratcliffe Highway, and there I met the tiger. Everything that came after followed from that. I believe in fate. Fall of the dice, drawing of the straw. It’s always been like that. Watney Street was where we came to rest. We lived in the crow’s nest of Mrs Regan’s house. A long flight of steps ran up to the front door. Railings round the basement area enclosed a deep, dark place where men gathered nights to play cards and drink strong liquor. Mrs Regan, a tall, worn woman with a pale, startled face, lived under us with an ever-changing population of sailors and touts, and upstairs lived Mr Reuben, an old black man with white hair and a bushy yellow moustache. A curtain hung down the middle of our room, and on the other side of it two old Prussian whores called Mari-Lou and Silky snored softly all day long. Our bit of the room had a window looking over the street. In the morning the smell of yeast from the baker’s opposite came into my dreams. Every day but Sunday we were woken early by the drag of his wheelbarrow over the stones, and soon after by the market people setting up their stalls. Watney Street was all market. It smelled of rotten fruit and vegetables, strong fish, the two massive meat barrels that stood three doors down outside the butcher’s, dismembered heads of pigs sticking snout upwards out of the tops. Nowhere near as bad as Bermondsey, which smelled of shit. I didn’t realise Bermondsey smelled of shit till we moved to the Highway. I was only a child. I thought shit was the natural smell of the world. To me, Watney Street and the Highway and all about there seemed sweeter and cleaner than anything I’d ever known and it was only later, with great surprise, that I learned how others considered it such a dreadful smelly hole.

Blood and brine ran down the pavement into the gutters and was sucked into the mush under the barrows that got trodden all day long up and down, up and down, into your house, up the stairs, into your room. My toes slid through it in a familiar way, but it was better than shitty Thames mud any day.

Flypapers hung over every door and every barrow. Each one was black and rough with a million flies, but it made no difference. A million more danced happily about in the air and walked on the tripe which the butcher’s assistant had sliced so thinly and carefully first thing that morning and placed in the window.

You could get anything down Watney Street. Our end was all houses, the rest was shops and pubs, and the market covered all the street. It sold cheap: old clothes, old iron, old anything. When I walked through the market my eyes were on a level with cabbages, lumpy potatoes, sheep’s livers, salted cucumbers, rabbit skins, saveloys, cow heels, ladies’ bellies, softly rounded and swelling. The people packed in, all sorts, rough sorts, poor sorts, sifting their way through heaps of old worn shoes and rags, scrabbling about like ants, pushing and shoving and swearing, fierce old ladies, kids like me, sailors and bright girls and shabby men. Everyone shouted. First time I walked out in all that I thought, blimey, you don’t want to go down in that muck, and if you were small you could go down very easy. Best stay close by the barrows so there’d be something to grab a hold of.

I loved running errands. One way was the Tower, the other Shadwell. The shops were all packed with the stuff of the sea and ships, and I loved to linger outside their windows and hang around their doors getting a whiff of that world. So when Mrs Regan sent me out for a plug of bacca one day for Mr Reuben, it must have taken me at least a half an hour to get down to the tobacco dock. I got half an ounce from one of the baccy women and was on my way back with my head in a dream, as was the way, so I thought nothing of the tray of combs dropped on the pavement by a sallow girl with a ridge in her neck, or the people vanishing, sucked as if by great breaths into doorways and byways, flattened against walls. My ears did not catch the sudden stilling of the Highway’s normal rhythms, the silence of one great held communal breath. How could I? I did not know the Highway. I knew nothing but dark water and filth bubbles and small bridges over shit creeks that shook no matter how light of foot you skipped over. ‘This new place, this sailor town where we will stay now nice and snug awhile, Jaffy-boy,’ as my ma said, all of it, everything was different. Already I’d seen things I’d never seen before. This new labyrinth of narrow lanes teemed with the faces and voices of the whole world. A brown bear danced decorously on the corner by an alehouse called Sooty Jack’s. Men walked about with parrots on their shoulders, magnificent birds, pure scarlet, egg-yolk yellow, bright sky blue. Their eyes were knowing and half amused, their feet scaly. The air on the corner of Martha Street hung sultry with the perfume of Arabian sherbet, and women in silks as bright as the parrots leaned out from doorways, arms akimbo, powerfully breasted like the figureheads of the ships lying along the quays.

In Bermondsey the shop windows were dusty. When you put your face close and peered, you saw old flypapers, pale cuts of meat, powdery cakes, strings of onions flaking onto yellowing newsprint. In the Highway the shops were full of birds. Cage upon cage piled high, each full of clustering creatures like sparrows but bright as sweets, red and black, white and yellow, purple and green, and some as gently lavender as the veins on a baby’s head. It took the breath away to see them so crowded, each wing crushed against its fellows on either side. In the Highway green parakeets perched upon lamp posts. Cakes and tarts shone like jewels, tier on tier behind high glass windows. A black man with gold teeth and white eyes carried a snake around his neck.

How could I know what was possible and what was not? And when the impossible in all its beauty came walking towards me down the very middle of Ratcliffe Highway, why would I know how to behave?

Of course, I’d seen a cat before. You couldn’t sleep for them in Bermondsey, creeping about over the roofs and wailing like devils. They lived in packs, spiky, wild-eyed, stalking the wooden walkways and bridges, fighting with the rats. But this cat …

The Sun himself came down and walked on earth.

Just as the birds of Bermondsey were small and brown, and those of my new home were large and rainbow-hued, so it seemed the cats of Ratcliffe Highway must be an altogether superior breed to our scrawny north-of-the-river mogs. This cat was the size of a small horse, solid, massively chested, rippling powerfully about the shoulders. He was gold, and the pattern painted so carefully all over him, so utterly perfect, was the blackest black in the world. His paws were the size of footstools, his chest snow white.

I’d seen him somewhere, his picture in a poster in London Street, over the river. He was jumping through a ring of fire and his mouth was open. A mythical beast.

I have no recall of one foot in front of the other, cobblestones under my feet. He drew me like honey draws a wasp. I had no fear. I came before the godly indifference of his face and looked into his clear yellow eyes. His nose was a slope of downy gold, his nostrils pink and moist as a pup’s. He raised his thick, white dotted lips and smiled, and his whiskers bloomed.

I became aware of my heart somewhere too high up, beating as if it was a little fist trying to get out.

Nothing in the world could have prevented me from lifting my hand and stroking the broad warm nap of his nose. Even now I feel how beautiful that touch was. Nothing had ever been so soft and clean. A ripple ran through his right shoulder as he raised his paw – bigger than my head – and lazily knocked me off my feet. It was like being felled by a cushion. I hit the ground but was not much hurt, only winded, and after that it was a dream. There was, I remember, much screaming and shouting, but from a distance, as if I was sinking underwater. The world turned upside down and went by me in a bright stream, the ground moved under me, my hair hung in my eyes. There was a kind of joy in me, I do know that – and nothing that could go by the name of fear, only a wildness. I was in his jaws. His breath burned the back of my neck. My bare toes trailed, hurting distantly. I could see his feet, tawny orange with white toes, pacing the ground away, gentle as feathers.

I remember swimming up through wild waters, the howling of a million shells, endless, timeless confusion. I was no one. No name. Nowhere. Then came a point where I realised I was nothing and that was the end of the nothing and the beginning of fear. I never had a lostness like that before, though many more were to come in my life. Voices came, piping in from the howling, making no sense. Then words—

he’s dead, he’s dead, he’s dead, oh, lord mercy – and the hardness of stone, cold beneath my cheek, sudden.

A woman’s voice.

A hand on my head.

No no no his eyes are open, look, he’s … there, fine boy, let me feel … no no no you’re all fine …

he’s dead he’s dead he’s dead …

there you come, son …

here you come …

And I am born. Wide awake sitting up on the pavement, blinking at the shock of the real.

A man with a big red face and cropped yellow hair had me by the shoulders. He was staring into my eyes, saying over and over again: ‘There, you’re a fine boy now … there, you’re a fine boy …’

I sneezed and got a round of applause. The man grinned. I became aware of a huge mob, all bobbing their heads to see me.

‘Oh, poor little thing!’ a woman’s voice cried out, and I looked up and saw her at the front of the crowd, a woman with a startled face and mad wiry hair, wild goggly eyes made huge and swimmy by bottle-bottom spectacles. She held a little girl by the hand. The crowd was like daubed faces on a board, daubed faces with smudged bodies, bright stabs of colour here and there, scarlet, green, royal purple. It heaved gently like a sea and my eyes could not take it in, it blurred wildly as if blocked by tears – though my eyes were dry – blurred and shivered and whirled itself around with a heaving burst of sound, till something shook my head awake again and I saw clearly, clearer than I had ever seen anything before, the face of the little girl standing at the front of the crowd holding her mother’s hand, drawn sharp as ice on a mess of fog.

‘Now,’ said the big man, taking my chin in his fist and turning my face to look at him, ‘how many fingers, boy?’ He had an accent of some kind, sharp and foreign. His other hand he held up before me, the thumb and small finger bent down.

‘Three,’ I said.

This brought another great murmur of approval from the crowd.

‘Good boy, good boy!’ the man said, as if I’d done something very clever, setting me on my feet but still holding me by the shoulders. ‘Fine now?’ he asked, shaking me gently. ‘Very fine, brave boy. Good boy! Fine boy! Best boy!’

I saw tears in his eyes, on the rims, not falling, which seemed strange to me as he was smiling so vigorously and showing a perfectly even row of small, shiny white teeth. His wide face was very close to mine, smooth and pink like a cooked ham.

He hoisted me up in his arms and held me against him. ‘Say your name, fine boy,’ he said, ‘and we’ll take you home to Mamma.’

‘Jaffy Brown,’ I said. I felt my thumb in my mouth and whipped it out quick. ‘My name is Jaffy Brown and I live in Watney Street.’ And at the same moment a dreadful sound rose upon the air, as of loosed packs of hounds, demons in hell, mountains falling, hue and cry.

The red face suddenly thundered: ‘Bulter! For God’s sake, get him back in the crate! He’s seen the dogs!’

‘My name is Jaffy Brown,’ I cried as clearly as I could, for by now I was fully back in the world, though my stomach churned and heaved alarmingly. ‘And I live in Watney Street.’

I was carried home as if I was an infant in the arms of the big man, and all the way he talked to me, saying: ‘So, what will we say to Mammy? What will Mammy say when she hears you’ve been playing with a tiger? “Hello, Mammy, I’ve been playing with my friend the tiger! I gave him a pat on the nose!” How many boys can say that, hi? How many boys can go walking down the road and meet a tiger, hi? Special boy! Brave boy! Boy in ten million!’

Boy in ten million. My head was swelled to the size of St Paul’s dome by the time we turned into Watney Street with a crowd of gawkers trailing after.

‘I been telling you what might happen, Mr Jamrach!’ shrilled the bespectacled woman with the little girl, bobbing alongside. ‘What about us? What about us what has to live next to you?’ She had the Scots burr and her eyes glared.

‘The beast was sleepy and full,’ the man replied. ‘He ate a hearty dinner not twenty minutes since, or we’d never have moved him. I am sorry, this should not have happened and will never happen so again.’ He knuckled a tear from the side of one eye. ‘But there was no danger.’

‘Got teeth, hasn’t it?’ cried the woman. ‘Claws?’

At which the girl peeped round her mother’s side, clutching onto a scrap of polka-dot scarf wrapped round her neck and smiling. It was the first smile of my life. Of course, that is a ridiculous thing to say; I had been smiled at often, the big man had smiled at me not a minute since. And yet I say: it was the first smile, because it was the first that ever went straight into me like a needle too thin to be seen. Then, dragged a bit too fast by her wild-eyed mother, she tripped and went sprawling with her hands splayed out, and her face broke up. A great wail burst out of her.

‘Oh, my God,’ said her mother, and we left the two fussing at the side of the road and went on through the market stalls to our house. Mrs Regan was sitting on the top step, but jumped to her feet and stood gaping when she saw the band of us approach. Everyone babbled at once. Ma came running down and I threw out my arms for her and burst into tears.

‘No harm done, ma’am,’ Mr Jamrach said, handing me over. ‘I am so sorry, ma’am, your boy was scared. A dreadful thing – a weakness in the crate, come all the way from Bengal – pushed out the back, he did, with his hindquarters …’

She set me on my feet and brushed me down, looking hard in my eyes. ‘His toes,’ she said. She was pale.

I looked wonderingly at the gathering crowd.

‘Ma’am,’ Mr Jamrach began, reaching into his coat and bringing out money. The girl and her ma were back. She’d scraped her knees and looked sulky. I saw Mr Reuben.

‘I got your baccy,’ I said, reaching into my pocket.

‘Why thank you, Jaffy,’ Mr Reuben said, and gave me a wink.

The Scots woman started up again, though now she’d changed sides and was defending Mr Jamrach as a great hero: ‘Ran after it, he did! Never seen anything like it! Grabs it like this, he does,’ letting go of the little girl’s hand to demonstrate how he’d leapt on its back and grabbed it by the throat, ‘sticks his bare hands right down its mouth, he did. See. A wild tiger!’

Ma seemed stunned and a bit stupid. She never took her eyes off me. ‘His poor toes,’ she said, and I looked down and saw them bleeding where they’d been pulled over the stones, and it brought the realisation of pain. I felt where the tiger had made my collar wet.

‘Dear ma’am,’ Mr Jamrach said, pressing money into Ma’s apron, ‘this is the bravest little boy I ever encountered.’

He gave her a card with his name on.

We ate well that night, no hunger sickness for me. I was very happy, filled up with love for the tiger. She washed my toes with warm water and rubbed them with butter she got from Mrs Regan. Mr Reuben sat in our room sucking on his pipe, and all the neighbours jostled at our door. It was like a carnival. Ma was tickled pink and kept telling everyone, ‘A tiger! A tiger! Jaffy got carried off by a tiger!’

The tiger made me. When my path and his crossed, everything changed. After that, the road took its branching way, willy-nilly, and off I went into the future. It might not have been so. Nothing might ever have been so. I might not have known the great thing that came to pass. I might have taken home Mr Reuben’s baccy and gone upstairs to my dear ma and things would have gone altogether differently.

The card sat propped importantly on the mantelpiece next to Ma’s hairbrush and a jug of wispy black feathers, and when Mrs Regan’s son Jud came home from work he read it to us.

Charles Jamrach Naturalist and Importer of Animals, Birds and Shells