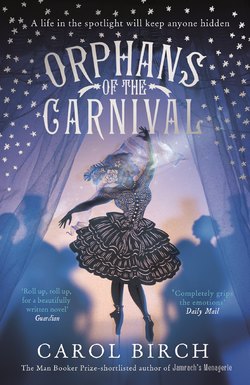

Читать книгу Orphans of the Carnival - Carol Birch - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеHot night, summer 1983. These were not nights for sleep, too febrile, too sweaty. Rose, walking home from some eternal flop-out, some smoky mustering in Camberwell, twoish, threeish, singing sotto voce the Heart Sutra to lighten the road (still the length of Coldharbour Lane to go) stopped still when the sky growled. A cosmic dog, big one with teeth. She was drunk enough to look up and laugh out loud. What the hell, there was no one around. A change of pressure, a flicker of lightning, then the first high murmur of rain.

Rose had sad brown eyes with tired hollows beneath, a wide big-lipped mouth and hair that stood out all around her head, thick, black and wiry. A scar sliced through her right eyebrow, giving that eye a slight droop at the outer corner. The years had rolled her into her thirties, thin and rakish, somewhat tousled and rough around the edges, and it was OK. The fear was at bay. As the rain set in, she turned her face up. It was good to be drunk. Simply wonderful sometimes to fray the edges, crank up the contrast. All she had on was a loose silky top and some old jeans, and she was getting soaked, but it was nice. She walked on, savouring the dark empty street and the way the soft hissing of late night traffic from Denmark Hill, and the lights shining on the wet pavement, made everything romantic.

Ahead of her, half way down Love Walk, was a skip piled high with rubbish. She never could resist a skip, particularly one full of the dregs and leavings of a house clearance. Whenever she came upon one, and London was awash with them, she stopped and had a good rummage and rescued anything that moved her. Many things did. When she was small, she’d bestowed consciousness on the things around her. Not just dolls and soft toys, but books, clothes, crockery, chairs, teapots and hairbrushes, rugs and pencils, even the corners of rooms and the turns of staircases, the gentle purring sound her bedroom window made when a car’s engine idled in the street outside, or the feathery stroking sensation in her chest when she was nervous with someone. All these things she’d named and given personalities.

She didn’t do it now, of course. But still—

Oh! Poor piece of paper, she’d think, passing a torn scrap in the street. Poor grape, last on the stalk, missing its friends and wondering why no one wants it.

This skip was nothing special, a pile of rags and rubble. She walked round it. A drop of rain hung on one eyelash, quivering in the edge of sight. Askew on the heap was a scattering of debris, shadowy nothings, in their very nothingness as heart-wrenching as anything, she thought, but you couldn’t stop for everything. The doll’s remains lay half in, half out of a doorless microwave oven near the top of the mound. She had to clamber aboard and scramble a bit to reach him. He was naked and limbless, with brown leathery skin, and a big head so damaged that his face resembled an untreated burns victim, the mouth a raised gash, the nose and ears pock-marked craters. One eye, made of glass, was sunk deep in his skull. The other was a black hollow.

‘Poor baby,’ she said, picking him up, cradling him sentimentally in her arms for a long moment before shifting him to her shoulder and patting his back. ‘Poor, poor baby,’ swaying happily in the rain.

She took him back to the ridiculous rambling old tip of a house on Coldharbour Lane where she lived, four enormous floors filled with escapees from small crap towns the length and breadth of the land. The air was an essence of all the people who’d ever passed through, and even though it was the middle of the night, the house had a faint hum of people doing things behind closed doors.

Rose went up to her flat at the top of the house. A waft of incense and dope greeted her when she opened the door. Inside was like an Arabian souk, all coloured hangings and cushions, mirrors, embroidery, long-fingered plants tumbling down deep purple walls. The room was full of stuff she’d brought home from skips and gutters and pavements, shelves full of things she felt sorry for. Old match-boxes and broken jewellery, bits of paper, sticks, fragments, remnants, residues, boxes, knick-knacks, broken things, the teeming leavings of the world.

‘Poor thing,’ she said, putting the maimed doll among her Indian cushions as if it were a cuddly toy, sitting back on her heels and looking into its round black face. The empty holes of the eyes and mouth conveyed an impression of sweetness.

‘Tattoo,’ she said.