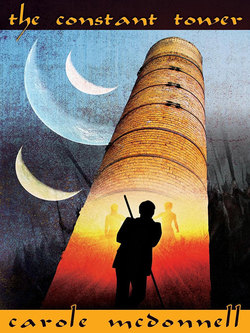

Читать книгу The Constant Tower - Carole McDonnell - Страница 9

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 3

CHIEF TSBOSSO

Through their communal echo-location, the towers of King Nahas’ royal longhouse, the tower Queen Hinis and the women would use to feast with the Peacock Clan women, and Tsbosso’s two Peacock Clan towers spontaneously created a closed feasting hall. All other longhouses—Wheel Clan, Peacock Clan and the great clans—spread out around them in all directions.

In his annals, Psal wrote:

In forty-nine ruined cities of Odunao, the truce festivals.

And in the Eastern Ruined City, sixty-seven Peacock longhouses,

Seventy-eight Wheel Clan longhouses.

Netophah’s mother’s clan was there.

White-haired, eyes like the crescent moon, the Waymaker clans—a good, gentle, wise people.

But scattered—unwilling to grasp and hold, looking only toward The Permanent Home.

They lived as nomads, taming regions then moving on.

The Grassrope clans—dark-haired and sallow. A filthy, loutish, selfish, grasping clan.

Stout from gobbling, with desperate hungry greedy eyes.

Hinis’ people—the Macaw clan, a people skilled in survival.

Hinis greeted her brother, Bukko, loading their baskets with fine rarities;

All these clans lived in peace with the Wheel Clan.

Then the great and noble Peacock Clans!

Expert, their mastery of animal science.

Out of Tsbosso’s longhouse came lions and reptiles, as docile as lambs.

Of all the great clans, only the all-female Voca was absent.

But who was surprised at that? The Voca hated all male-ruled clans,

From within the Wheel Clan, Ezbel the Voca Queen was born.

She hated them above all clans.

The smaller clans also feasted.

For one day, equal to the great tribes.

And in the distance, the Great Eastern Ruined City and the Great Mesa stood

Reminding all of the ancient time when night spoke of permanence and all the clans were one.

Freed from the duty of translating for his father, Psal clasped his staff and searched for Cassia among the festive crowds. Mark you how gracious, how charming, how exuberant the young prince was when not among his own clan. How he leaped on that withered leg and scampered about with joy! I have forgotten what I am: a prince, forgotten my own peace. Surrounded by other clans, I find myself again. Now, girls from the Waymaker Clans stroked his face; women and men from the Grassrope clans flirted with him, running their fingers through his flowing dark curls; Peacock Clan girls flitted past, flirting in their dyed buckskin skirts, their faces painted like butterflies or virginal white; warriors and studiers from clans large and small bowed as they passed him, warriors and studiers from other Wheel Clan longhouses, pointed at him: That is the Firstborn of the Wheel Clan!

But where was Cassia? She should be with the unmarried girls, flirting with young men, teasing old warriors, showing off her beauty. Finding her should not be so difficult. At last Psal saw her, but she walked among the married Peacock women. Her face was no longer covered in white clay but with red. The roundness of her stomach could not be mistaken. Still, hope was securely lodged in the boy’s heart as he raced toward her. She half-smiled when their eyes met and walked toward him, glancing around her.

“Why are you here, among these married…” A marriage tattoo on her cheek. Even if she has married someone since the last time we met, it is possible her husband has died.

Cassia carried a large wooden bowl. She placed it atop a broken stone column. The bowl of steaming Yisin grain wobbled, but did not fall.

Psal’s heartstrings tightened. Could you not have waited for me? “So you’re another man’s wife now?”

“I have wanted to see you…to explain,” she said in the Wheel Clan tongue and kissed his cheek tenderly. “But Father has kept me from you all these moons. When you sent messages to the towers, he did not tell me. And all this morning he ordered me to stay with the married women.” Tears trailed through the clay on her brown cheeks. “A chief’s son from the Full Blossom Peacock Clan gave Father much pharma science for me. I pleaded and begged but—”

“But you promised.”

“My father broke my pledge, Psallo. Not I. My heart continues to desire only you.”

“Does he…your new husband…beat you?”

More tears flowed. “No more or less than is expected. But I must warn you—” She stopped speaking suddenly and trembled like a child caught in a forbidden act.

Psal turned. Old Chief Tsbosso strode toward them. Cassia lifted her grain bowl and disappeared into the throng of married Peacock Clan women.

Psal’s head throbbed. “Are the truce negotiations finished already?” he asked when the old man stood before him. Why have you forced her to marry one who beats her, one she does not love? He reached out and straightened the mantle slipping from the old man’s shoulders.

Tsbosso’s gnarled fingers pinched Psal playfully on the right ear. “Many clans seek treaties with your father. Small things first, then important things. And you, my boy?” Tsbosso stroked the staff he had given Psal. “Has this helped you? You lean on it like a prince born among my people.”

“The others deem me weak when I use it. But it is often necessary to lean upon it.”

“You must use it, my boy! Your tender heart, you cannot help. The body, however, can be trained to stand straight and strong. You don’t want to look puny, do you?”

Psal nodded. He’s pretending not to see my anger or his daughter’s heartbreak, because he knows he’s the cause of it.

They walked toward Tsbosso’s longhouse and sat on the ground near its main entrance. Together, they looked out at the festival, talking of this and that, of ancient lore and new discoveries, of illness and health, of the cruel judgments made by unkind uncaring hearts, of clans and traditions.

The old man scratched his head. “I’ve warned your father more times than I can remember that sending apprentice studiers off to roam the world with disgruntled old masters is a dangerous practice. No, no, that kind of thing never comes to any good. And the Master of the Wintersea? The bitterest of Wheel Clan studiers? No, I knew it would not work. And have I not been proven right? But who can tell Nahas anything?”

“Indeed,” Psal said. Like Nahas, none can tell you anything either.

“Come now, my boy! You look like a cliff-dweller who has just realized night has fallen and he’s two leagues from home.” He gestured widely. “We’re at a festival. Beautiful girls abound, and you’re a king’s son. Now, this old man needs your help to get up.”

Psal stood and helped the chief rise.

On his feet again, the old man said, “My boy, she is eight years older than you are, and she has a temper as bad as yours. Living with her would’ve led to one fight after another.”

“I liked her temper. I liked everything about her. More than that Full Blossom Clan chief’s son could.”

He waited for the old chief’s rebuke, but whether because Psal was a king’s son or because Psal was a particular favorite, Tsbosso ignored the outburst. Instead, the old man pointed. “Your friend has always liked old women.”

Psal turned. Ephan stood beside a tree shyly watching Tzaddi, Tsbosso’s oldest daughter. A beautiful woman, but ill-treated by her father for some past trespass, she stood next to Poh, Tsbosso’s oldest son and Psal’s childhood friend. Psal frowned. Cassia probably had such a husband, tall, with a body strong as a tree, nature-blessed and healthy.

“Brother Psallo,” Poh called as he walked past. “My other self, my twin.”

Psal tried to smile.

Tsbosso slapped Psal on the shoulder. “What do you think of marrying my youngest girl, the one we call ‘Moonlight’?”

Psal’s mouth fell open. “Moonlight?” he echoed. “She’s a jewel.”

“A jewel indeed!” Tsbosso said. “As out of reach as the elusive moonlight. But not out of reach for you, Wheel Clan Firstborn.”

Lovely, good, and wise was Moonlight. But his heart did not sing for her. “I don’t want her. Why do you offer her?”

“These skirmishes must stop, my boy. Or our clans will destroy each other.”

“Let the matter rest,” Psal said. “Make me less important in your eyes. Betroth Moonlight to Netophah if you wish to prevent skirmishes between our people. They’re of the same age.”

“I know that Nahas disdains the thought of letting his studiers marry outside his clan. But peace must be attained. Tell me, if Netophah were to marry my daughter, what part of your tower science is Nahas willing to share? Would the king teach us how to keen towers from afar?”

Psal shook his head. “Great Chief, Father will not give you tower science. No, not even if Netophah becomes your son. And as for far-off keening, if you knew that skill you would vie with us for uninhabited and abandoned towers. Ask for some of our oil regions. We have much oil. A small price to pay for an alliance.”

“Would he show us how to use false notes to disguise our tower songs?” the Chief asked.

Psal chuckled. “I do not wish to rebuke the chief of a great clan, but why persist in asking for tower science? Great Chief, speaking to Nahas of towers will come to no good.”

“But, my boy, consider,” Tsbosso pressed. “Today, my youngest son and several warriors must remain with our women in their longhouse as they journey to feast with your women. All across Odunao, as your women and our women meet to feast, my poor warriors are bound to stay with our women. Why? Because someone has to keen our women home. It is a great bother. But if we knew how to keen from afar.…”

“If you taught your women how to keen towers, as we teach ours, you wouldn’t have this great bother. Great Chief, your ability to charm fierce beasts interests Nahas. Offer him that. But no talk of towers, please! Yesterday, we found a new region. Fertile, with lakes and meadows. We burned the forest, but did little more. Wild animals still roam free. Since we haven’t labored on it, Father may give it to you. Yes, I think he would. He, too, is tired of these skirmishes.”

“Well then, I will not ask of tower science. But you send me such sad tower songs, about how lonely you are among your own people. Tell me, if you married one of my daughters, would Nahas allow you to live primarily in our longhouse? If you were Tsbosso’s son-in-law, none would dare mock you, even if you lived among your own people.”

“Even after marriage I will continue to live with my clan. Father thinks I’m weak, you see, and ready to betray him.”

Tsbosso looked appropriately shocked. “Oh, how unfairly that man treats you! You are not weak.” He glanced at a table where Cyrt, Gaal, and Nahas feasted. “Think of it, Psallo. A marriage into a clan that respects you! Unimpeded explorations! The respect of being the Father of a peace child. Perhaps chief of your own longhouse. I must help your father see clearly.”

“Forget me and my sorrows, Great Chief. For our people’s sake, make Netophah your son-in-law. My heart is still with Cassia.” Psal bowed then walked over to Ephan.

“Ask the woman to lie with you,” he told Ephan, “or stop staring at her.”

“I’ll have better luck exploring the abandoned tower than exploring that beauty.” Ephan gave a wistful sigh. “So will Cassia allow you to lie with her again? I haven’t seen her as yet.”

“Cassia’s been given away.”

“Bad luck. I know you loved her.”

“I did, yes. I will always love her.” Psal pointed at the remains of the ancient aqueduct rising high above the dusty road leading to the Great Mesa. “The abandoned tower first. Then the Ruined City, then the Mesa.…”

Ephan was still looking at Tzaddi. Psal hoped Tsbosso’s daughter would favor his friend.

“She is a lovely one, isn’t she?” Psal said. “She seems to like you as well.”

Ephan blushed, turned toward the ancient gate. He had prepared a small, wheeled cart with supplies, and they set off on their journey.

They had not gone far from the feast grounds when Psal turned to see Netophah following them.

“Return home!” Psal yelled back at him. They pelted him with stones and twigs but he continued following them.

Thus, the three sons of King Nahas walked toward the abandoned tower—the tall, puny, and peevish Firstborn, the too-pretty albino foundling, and the well-favored, nature-blessed heir of all Wheel Clan lands.