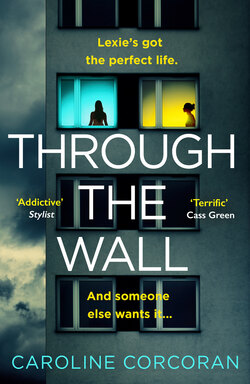

Читать книгу Through the Wall - Caroline Corcoran - Страница 9

3 Harriet December

Оглавление‘I cannot believe how many chain restaurants are in this neighbourhood,’ says Iris, using a tone for the words ‘chain restaurants’ that most people reserve for ‘terrorism training centres for toddlers’ and grinning widely through her astute observation. ‘You know?’

I know.

I take a large glug of wine and feel my cheeks singe. She thinks where I live is embarrassing. She thinks I’m embarrassing. Everyone here thinks I’m embarrassing. I have been taking extra wine top-ups this evening and the room is starting to spin. I stare at her, try to bring her into focus.

Really, I think, Iris should be trying to bring me into focus. Because the truth is that she – they – have no idea who I am. What I’m capable of, what my real name is and who the real me is. What is at my core and what I did, nearly three years ago before they knew me.

Anyway, I think, flooded with rage suddenly as they speak around me: I love Islington. Take somebody socially awkward and place them in the heart of one of London’s busiest areas and they will adore you. They will never need to make small talk with the butcher. They won’t have a favourite restaurant because they have sixty within walking distance and when they do, it will change hands and become a pop-up Aperol bar anyway. You can know no one and that doesn’t mark you out as odd: it’s simply the way things are. You can have a secret, because you can hide away.

I recover from the insult quickly. A couple of drinks later, I am talking with unwarranted confidence about British political turmoil in the Eighties while intermittently chair dancing to Noughties pop music. I’m very drunk – I’m often very drunk – and I’m laughing. But it is an empty laugh because I don’t know the people I’m laughing with.

Next to me on my sofa is a man named Jim, ‘incredibly talented’, gay, talks about being an introvert often and loudly. Opposite me is Maya, who has been nursing her glass of Pinot Noir for the last two hours, despite my best attempts to top her up, loosen her up, liven her up, something her up. On the floor, barefoot and knees pulled to their chests, are Buddy and Iris, who live in Hackney and were probably christened Sarah and Pete and who rarely leave the house without making sure a copy of Proust is sticking out of their bags. A Christmas hat sits joylessly atop Iris’s shiny brunette bob.

I look around at all of them and try to feel something but there is nothing. Or there is worse than nothing; there is a low-level stomach ache that tells me I feel awkward and sad and that this gathering in my home is the opposite of friendship.

Merry fucking Christmas.

Last month, I met all of the people currently squeezed into my lounge for the first time. I am a songwriter, we are working on a musical together and I invited them over for Christmas drinks. For God’s sake, I even wheeled out a box of Christmas crackers.

I do this with everyone I work with. We usually rearrange around four times and people’s excuses are vague, but I am persistent. They all capitulate, eventually.

I’m still trying to find something that makes me stop craving the city’s anonymity; something that claims me as its own, despite four years passing since I left my native Chicago. I’m trying, desperately, to be social. But sometimes I think the truth is that when you carry a history like the one I carry, you can never truly grow close to people. It’s too risky. Too exposing.

I pull a cracker with Buddy and lose.

But still, I keep trying.

‘So, Harriet, are you seeing anyone?’ asks Introvert Jim, loudly, bolshily, butting in rudely to my thoughts.

I shake my head, top up my wine.

‘No, Jim,’ I slur, matching him for loudness as my drink glugs into the glass. I forget to offer a top-up to anybody else. ‘I am single.’

Oh, I am very, very, very much single. Unhappily single. I am not content being me. I’m not joyous in my own company. I am awkward and I make terrible decisions and I want another half to make 50 per cent less me. I aim to dilute myself, like a cordial.

‘Karaoke!’ I say, fuelled by wine and the panic that people may leave, and Iris and Buddy find it ironic enough – like the Christmas hats – to join in. Maya slips into her denim jacket and slopes off, giving me a pitying look that sets a flare off inside me as she says goodbye. Jim can be persuaded once I find him a dusty bottle of tequila for a shot.

These colleagues may not be an immediate solution to my solitude, but perhaps one day it will come in the form of a man who one of them knows.

Plus my parties, alcohol-fuelled as they are, rarely begin and end at my colleagues.

It happens, always, as it is happening tonight. The door is propped open so that my guests can pop downstairs for cigarettes. I live next to the elevator and what I never envisaged – given how antisocial my neighbours are in daylight – is that late at night, people started coming in the other direction, too. Peering in to see what’s happening. Hearing a song that they like. Grabbing a beer.

So it could be one of those, too; an unknown neighbour who comes for the alcohol but stays for me. I might not be perfect, but I have things to offer. Enough to hope that one day, someone might invite me back, might claim me.

There are hundreds of flats in our tall, imposing tower block, and most of them are inhabited by men and women in their twenties and thirties who don’t have children and can get drunk on Tuesdays without much consequence beyond a hangover they have to hide under carbs the next day at their desk. If they live here even as renters then they are mostly paid well and work hard for long hours, so that their evenings take on a desperate quality. Enjoy it, make the most of it, drink it, snort it before you’re back in a meeting at 8 a.m.

The building, with its modern feel, feels to me like it aids this. The sparse, airy lobby is an anonymous retreat, painted head to toe in magnolia with just a desk for the concierge and a sole plant that never wilts but never grows. Is it fake? When I stare at it, I can’t tell. I wonder if people ask the same thing about me.

In the lobby is an unplaceable but specific scent that never alters. The temperature’s always exactly what you want it to be, whatever the season.

At times it reminds me of an airport. People pass through, collect their parcels, take off in the elevator up to the eighth floor, and there are so many flats that you can easily never see them again. Occasionally, it reminds me of somewhere darker: of the psychiatric hospital where I used to be a patient. A coincidence? Maybe this is what I want from a home, I think. Utter sterility.

Now, my neighbours traipse into my home, three, four, every half-hour. They are on their way back from their work drinks or their dinners and they stick their hazy heads in to see what’s happening. Someone – me, most likely – shoves a wine glass into their hand and the next minute it is 1 a.m., and a city banker in his early twenties who I’ve never seen before is kissing Chantal from the fifth floor and vowing to move with her to a hippy commune in Bali. Chantal, like me, is a rare exception in this building to the city-banker rule, but I’ll get to that in a minute. By day, my neighbours are antisocial and aloof; by night, they are debauched and overfamiliar, revelling in their freedom. Happy mediums are not what we do in Zone One.

Did I make an idiot of myself? Chantal will message tomorrow, inevitably.

The message will come from her sofa, where she lies every day thinking about retraining as a masseuse. Chantal was made redundant from her job in marketing a year ago and from a distance, it is clear that she is in a deep depression, which isn’t helped by the fact that her rich parents pay for her to lie still and be sad. She has no motivation to move. But at 1 a.m. Chantal is shining, lit by lamplight and Prosecco. At 1 a.m., Chantal and I are something approaching friends. At 1 p.m., we exchange awkward chat in the preprepared aisle in Waitrose.

‘I’d better head to …’ she will mutter, gesturing vaguely at some bread, or a door, or anywhere.

‘Yeah, I’d better get on, too,’ I’ll concur urgently before ambling back to my sofa.

But meeting somebody is a numbers game, that’s what my mom would say if we still spoke. If it wasn’t impossible for us to speak, after what I did. It’s a numbers game and I’m following that policy. Let the strangers in. Keep them coming.

The nights begin with wine offered politely and with small talk. And then they descend into strangers and a blurry chaos I spend most of the next day clearing up. It’s worth it, though – the mess is comforting. It gives me a purpose.

Again, tonight, my flat is full of unknown or barely known neighbours and the last of my colleagues who are heading home now at 2 a.m., slurring. As they wait for the elevator outside my flat I hear them through the door that’s been left, as ever, temptingly ajar.

‘She’s just a bit … much, you know?’ says Iris, her voice loud because she is drunk on the alcohol that I just gave her, for free, while she hung out in my home. She is talking about me.

Buddy concurs, as the world always has concurred on this. I’m a bit … much. I’m not quite the right amount. Not on target. Not the level of person you would ideally want. If I were a recipe ingredient, you’d tip a portion of me out, or balance me with salt. As I’m a person, I can’t be amended, so I remain a bit … much.

I sit against the wall behind the door listening to the rest of their thirty-second conversation on the topic of me before the elevator announces itself loudly. An hour later, when everybody else leaves, everything is quiet, and I hear a TV being switched off next door and the soft, kind padding of slippers on laminate floor.

I say goodbye to my next-door neighbour, Lexie, in my head. She never turns up at my parties, but I know her name because I have heard her boyfriend say it through the wall. And then I lie down on the sofa, mascara on the cushion from the start of tears that will go on and on and on until the moment that I finally fall asleep.