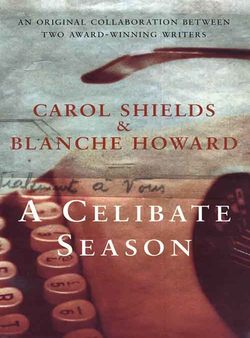

Читать книгу A Celibate Season - Carol Shields - Страница 5

Foreword

ОглавлениеCollaborating with

Carol Blanche Howard

Our family has a cautionary tale, part of the family folklore. It seems that two sets of aunts and uncles on opposite sides of the family became fast friends and decided to travel together for three months in Europe. (European travel was considered more exotic then than it is now.) After the travellers returned and my mother phoned to hear all about it, she found that neither couple was speaking to the other. Furthermore, they were never known to speak again. Explanations were not forthcoming. The aunt on my mother’s side confined herself to a disparaging sniff and made remarks about some people not knowing the limits of civilized discourse nor the need to accommodate anybody but themselves. Nothing, as far as I know, ever emerged that was so beyond the pale as to account for the disruption of what had seemed a solidly entrenched friendship.

How much more dangerous, then, is it for two artists to collaborate on a work! Gilbert and Sullivan, for instance, were renowned nearly as much for the depth and ferocity of their animosity as for their witty lyrics, and, indeed, at a forum at the annual Sechelt Writers’ Festival, one of the participants asked Carol Shields if she and her collaborator in A Celibate Season were still on speaking terms.

We were, and we are. Carol’s reputation, when we started the novel, was burgeoning, whereas mine had languished after my three novels were published. I jumped at her suggestion that we do a novel together, recognizing her generosity in wishing to spend time on a work that might very well not further her career, and indeed might use up valuable time more beneficially spent elsewhere.

Carol is generous, and she is loyal. I emphasize this because generosity and loyalty have not been givens among the writerly talented, a goodly number of whom have abused their gifts in the disservice of others. In his final years Truman Capote alienated lifelong friends and benefactors not so much by his drunken and obnoxious behaviour as by the cruelty with which he lampooned them. The Bloomsbury crowd, too, thought nothing of accepting hospitality and favours from the likes of Lady Ottoline Morrell and then, with amusing (in retrospect) bitchiness, or downright malice, cutting her to ribbons. This is Virginia Woolf, in a letter to her sister: “it is said that Garsington presents a scene of unparalleled horror. Needless to say, I am going to stay there,” even though Lady Ottoline is described as being “as garish as a strumpet.”

Carol and I first met in Ottawa in the early 1970s, when a mutual friend took me along to the Shields’ large brick house on the Driveway where Carol was hosting the University Women’s Club book discussion group. My first novel, The Manipulator, had been accepted, and Carol’s first small book of poems, Others, was being published. We soon recognized the other as a “book person”—by that I mean that the reference points we used for living our lives had come to a large extent from the voracious reading habits we had developed in childhood.

In 1973 the exigencies of politics booted my husband and me back to Vancouver, and I suppose Carol’s and my tentative friendship would have stayed at that level had it not been for the contract she was offered in 1975 for her first novel, Small Ceremonies. At the time, she was in France where her husband, Don, was attached to a university during a sabbatical. My next two novels had been accepted, and so I must have seemed like an expert to whom Carol could write and ask for advice.

I don’t remember what nuggets of wisdom I offered other than “Grab it,” but I do remember well the astonishment I felt when I read Small Ceremonies. I had not read Carol’s prose before, and I was, perhaps, unprepared for its magic: mature, elegant writing with the nicely turned and unexpected phrase. By the time I got to the very funny party scene where a woman is saying, “remember this, Barney, there’s more to sex than cold semen running down your leg,” I knew, with bolt-from-the-blue revelation, that I was dispensing advice to a quite extraordinary talent.

Somehow we fell into regular correspondence. Carol loves to get letters—once, visiting them in Paris, my husband and I were amused at the enthusiasm with which she watches for the daily mail, or twice-daily, as it is in France. She swoops down on the mailbox as if it might contain the meaning of life—and perhaps it does. Still, I suppose our regular letters back and forth over the years, even in the ‘70s before e-mail and faxes had begun whittling away at formal communication, was and is a somewhat Victorian diversion.

I stuck Carol’s letters in a file, and eventually I began to put in copies of my answers as well. The file of letters is three inches thick now, and as I riffle through them trying to determine when it was that we decided to collaborate, I settle on April of 1983 when she came to Vancouver for Book Week.

By then the Shields were living in Winnipeg while we were still in Vancouver. They had spent two years in Vancouver between 1978 and 1980, a time that gave Carol and me a chance to know that we enjoyed one another’s company and not just one another’s letters. And that our husbands liked one another. As everyone in a relationship of any sort knows, it frequently happens that the significant other is bored by or can’t stand the sight of his/her counterpart. Carol’s and mine is a lucky friendship; our husbands hit it off from the first. We had dinner parties; they sailed with us; we went dining and dancing with them.

Only two years and they were off to Winnipeg, where Don had accepted a job at the University of Manitoba. Now, besides writing letters about books, families, work, the state of the weather, and so on, we were beginning to read one another’s manuscripts (a practice we still continue) and in 1981 I was commenting on A Fairly Conventional Woman, wondering if Brenda should have slept with Barry in her old flannel nightgown. (Carol was sensible enough to keep the scene.)

I suppose an epistolary novel was a natural for us, although at that time it was a form that was being shunned. Carol was the one who noticed that the feminist revolution had so liberated women that there were bound to be career conflicts, and so we decided to have our husband and wife faced with separation. Beyond that we didn’t plan, which is the way I operate but is unusual for Carol. Usually she knows where she is going with her novels and is able to write three polished pages a day.

Separation has never happened to either of us in real life. Unlike our protagonists, Chas (for Charles) and Jock (for Jocelyn), Carol and I have settled quite happily wherever our husbands have taken us. This may be due in part to the social strictures of the times that shaped us; I was a young wife and mother in the ‘5os while Carol was still an adolescent, but in that decade when housework and husband-support was raised to what Galbraith dubbed a “convenient social virtue,” it seemed a natural thing to do and be. Indeed, to yearn otherwise carried social disapprobation. When entering the hospital in labour, Erma Bombeck attempted to have “writer” entered under vocation, but a no-nonsense nurse scratched it out and put in “housewife.”And, as Carol has pointed out, writing is a portable vocation that can be done satisfactorily whenever the children (five for Carol, three for me) are tucked into bed or off to school.

In A Celibate Season Chas says he’s not prepared to abandon the middle class, since “the good old middle class has, after all, been good to us.”The middle class is where most of us hang our hats, although following the century-defining ‘60s, many were bent on denying it. Jeans and headbands were in and skirts and pearls were out, and Carol and I joked at Writers’ Union meetings in Vancouver about the need to shed our middle-class images, since writers above all were not supposed to be co-opted by the middle class.

In the end, it is Carol who has done the co-opting. With her Jane Austen-like asides that prod our foibles and pretensions, she has carved out her territory from the milieu in which she lives. In an introduction to The Heidi Chronicles Carol wrote, “Feminism sailed into the sixties like a dazzling ocean liner, powered by injustice and steaming with indignation.” For a time the ocean liner came close to refitting itself as a warship, or even a destroyer, lobbing its ideological bullets at those with differing takes on the truth.

“Truth,” Iris Murdoch says, “is always a proper touchstone in art…requiring that courage which the good artist must possess.” Fiction is not the handmaiden of politics, any more than the bleaker side of sexual politics is the honest experience of every writer. We don’t lack for novels that crawl into the many hearts of our darkness, and bookstores are lined with thought-provoking essays by articulate feminists like Gloria Steinem. What we have lacked, and what Carol has brought us, is an intelligent and articulate witness to the ordinary and often happy lives of women and families.

Carol and I met—or rather, didn’t meet—Gloria Steinem once. At breakfast the day after A Celibate Season launched in Regina, we sputtered over an unpleasant review whose main preoccupation was with the names we had given our protagonists. By way of a restorative we hurled ourselves against an icy gale in minus twenty degree temperatures for several blocks to a bookstore. Almost nobody was there, except for a lone woman who was sitting in a chair waiting to sign books. “Who is it?” Carol whispered to me. “I think it’s Gloria Steinem,” I whispered back. It was. We didn’t introduce ourselves. Carol thought it might be intrusive—and I agreed—since we hadn’t read Steinem’s new book. I regret it now.

But I’m getting ahead of myself. When we began A Celibate Season, Carol wanted to write the male part, and so I kicked off the process with Jock writing from Ottawa, where she has accepted a position as legal counsel for a Commission looking into “The Feminization of Poverty.” I sent the chapter off to Carol on October 26, 1983: “Well here’s chapter one, and I can’t tell you how much more fun it is to write something for someone else’s eyes than just to write for the faceless mass who may or may not read it.”

It was enormous fun for us, lobbing curves at the other. “Killing off Gil was a stroke of genius.” “Please feel free to revive Gil.” I wrote that I laughed out loud at Chas’ irritated postscript, “Fuck the purple boots.”

When both Jock and Chas do something they can’t risk telling the other, we had, somehow, to transcend the limitations of the epistolary novel. The only solution in a two-way correspondence is the unsent letter, although Carol was bothered, initially, by what she feared might be “the narrative dishonesty of it.”

Since I was coming through Winnipeg in November of 1984, we vowed to complete the first draft by then. I stayed in the Shields’ lovely Victorian-style home, the kind with oak panelling and big halls and a wide, sweeping staircase. On a bitterly cold and slippery night (me smug in the superiority of Vancouver rain), we went to the university to see Carol’s delightful little play Departures and Arrivals, and the next day we worked diligently all day at the dining room table, each reading aloud our own letters and interrupting one another with corrections, cutting, adding, changing, arguing over commas. At five o’clock Carol announced that eight people were coming to dinner so we had to clear the table.

I remember that the evening was merry and that we involved the guests in a vigorous discussion of whether or not “A Celibate Season” was a good title. Some said yes, some said no, but nobody (including the authors) knew of a possible derivation that was pointed out later by an astute reviewer (Meg Stainsby, whose comments are included at the end of the novel): St. Paul, in a letter to the Corinthians, asserted that celibacy is desirable within a marriage, but only for a “season.” As far as we knew the title was entirely original, but we may have been deceived; the brain has its hidden ways, it can explore forgotten recesses and toss used tidbits up like newly minted gems.

Carol sent along two reworked chapters in short order, and in December came the “big” chapter, the one where Chas admits to his somewhat bizarre episode of infidelity. She worried that I might think it “unacceptably kinky”; instead I found the letter “wonderful, pathetic and touching.”

The end was in sight. Letters flew back and forth. We started sending the manuscript to publishers in January of 1985.

I thought it would be fun to try adapting the novel to the stage, and by September, while publishers were (very slowly) considering the novel, I was sending drafts of the play to Carol in France. “Davina is better in the play than in our book, funnier and fuller, also more likeable,” she wrote back. As for the novel, when Carol came to Vancouver in the spring of 1986 we still hadn’t sold it, and again we went over the manuscript. The first third, Carol wrote to me after spending a July weekend on it, was perhaps too slow, the second third really crackles, and the final third was perhaps too amiable. Re-worked once again, and once again I started mailing it out until we had racked up nine rejections. In the meantime, the play was faring well; it was being workshopped by the New Play Centre in Vancouver and when I sent it to the Canadian National Theatre Play writing competition, it was a finalist and came back with soul-restoring comments.

The Shields invited us to spend a week with them in Paris in the spring of 1987, and while there I read the galleys of Swann and was quite sure it would win the Governor General’s Award. It didn’t, although it was shortlisted.

By now the manuscript had been temporarily abandoned. Then at a conference in Edmonton I bumped into fellow writer and mutual friend Merna Summers. How did we expect to sell the novel, she asked, from a desk drawer? Get it out there, she urged, and she suggested Coteau Books. I sent it in September, and in May of 1990 Coteau agreed to publish it. In June we got word that the play would be produced by a small North Vancouver drama company in the fall.

That summer my husband and I rented a gite near the stone house the Shields had bought in France, and once more, in the sunny days of June, this time looking out over the lovely Jura mountains, serenaded by cows in the neighbouring fields, we went through the manuscript and began editing for publication.

Carol told me once that if she didn’t write she would become neurotic. I think this is true of most writers; Freud may have merely put a new spin on an old truth. Certainly writing is a search that may, like psychoanalysis, lead us into secret labyrinths where thoughts we had never suspected are discovered, where ancient and forgotten fears thrust themselves, like stalagmites, into consciousness, where we catch glimpses of desires so evanescent that they scatter like cockroaches before the light. And always, the compulsion, the need, to know more.

The following summer we were returning on the ferry after Carol’s appearance at the Sechelt Writers’ Festival and Carol was gently probing me about my thoughts on aging. (I am older than she is.) “Carol, are you asking me for the meaning of life?” I asked, and we both laughed, and then I said, “I’ll tell you what, if I find it I’ll phone you,” and, after a pause, I added, “and if you aren’t in, I’ll leave it on your answering machine.”