Читать книгу Little Prisoners - Casey Watson - Страница 7

Chapter 2

ОглавлениеFighting the need to gag, I ushered everyone inside, pasting a smile on my face, leaning down towards the children, and starting with the usual introductions.

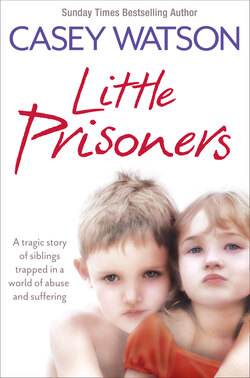

‘Now, you must be Olivia,’ I gushed, smiling warmly at the frightened little girl. Like her brother, she had dirty-greyish, straggly blonde hair, and such sad, sunken eyes – two huge blue pools in her pale face. ‘And you’ll be Ashton …’ I went on, smiling at the tousle-headed boy. His hair, I noticed, for all that it was matted around his head, was almost as long as his sister’s. He nodded nervously, as he stepped past me into the hall, his whole demeanour suddenly reminding me of a little boy in a Second World War film who’s just stepped off a train full of frightened evacuees and is determined to maintain a stiff upper lip. ‘You’re very welcome,’ I finished, grinning broadly at them both. ‘Come on,’ I said. ‘Come in. It’s lovely to meet you.’

I straightened again, shocked at how tiny they seemed. So much smaller and younger than the ages ascribed to them. I then turned my attention to the two adults. ‘Nice to meet you both,’ I said, proffering a hand, which, after disentangling themselves from the children, who were still clutching on to them, the man and the woman shook in turn. ‘And this is my husband, Mike,’ I finished. Mike duly did likewise, before saying his own cheerful hellos to the little ones, who visibly shrank back at the sound of his voice.

‘Great to meet you too,’ the female social worker said. ‘I wonder … could the children perhaps go and sit down somewhere? Watch some telly or something? You’d like that, wouldn’t you?’ she added, turning to her two charges. Ashton nodded.

‘Of course,’ I said, ‘Come this way, kids.’ I led them both into the living room and switched on the television, flicking through to find a cartoon channel for them to watch. Mike, meanwhile, I could hear, had led the two adults into the dining room, so we could all have a proper briefing over coffee before they left.

The children sat, huddled close to one another on the edge of the sofa, meekly and silently accepting the drinks of squash and biscuits that I’d already prepared in anticipation of their arrival. They looked I thought, a little like extras from Les Misérables. I tried not to think about their proximity to my soft furnishings. Head lice can’t jump, I reminded myself firmly, as I left them to it and went to join the adults.

Mike was pouring coffees when I walked into the dining room. ‘Here we are, love,’ he said, handing me my one.

The female social worker smiled across as I took my place at the table. ‘I’m Anna,’ she said. ‘We spoke on the phone. And this is Robert,’ she finished. ‘Robert Foster.’ He raised a hand. ‘He’s the family support worker attached to the children.’

Mike, the coffees dealt with, now sat down as well. ‘So,’ he said, ‘what can you tell us about these two?’

‘Not as much as we’d like,’ Anna immediately confessed. ‘I’ve only been working with the family for the last couple of months, you see. The last social worker on the case was involved with the family for six years, or so I’m told, but, regrettably, she’s on long-term sick leave right now, so I’m pretty new to the situation. All I can tell you is that there are three more children – all of them younger; two, three and four, they are – who were removed and found a placement two months back.

‘Five kids!’ Mike exclaimed, voicing my own thoughts. They’d been busy.

Anna nodded. ‘Indeed, but it’s these two, being older than the babies, who are proving problematic for us. Up till now the service has been unable to find anyone willing to take them.’

‘Why were they removed?’ I asked her. ‘I mean, I can see they’ve been neglected, but is that it? Is that the only reason?’

Both Anna and Robert looked slightly uncomfortable at the question, and it was Robert who now stepped in to answer. ‘Mainly,’ he said. ‘Yes, that’s about the size of it.

Gross neglect, quite a number of complaints, from various sources, and the parents, to be frank with you, seem incapable of looking after themselves, let alone five kids. Learning difficulties, both of them. Dad fairly mild but, in the mother’s case, really quite severe. So we’ve been going through the usual channels, of course – there’s a court hearing coming up soonish for a full care order, but as the hearing date’s got closer, and our investigations more frequent – and also more thorough, of course – it’s become increasingly clear that we’d be doing the kids a disservice if we left them with the parents any longer.’

‘But why so sudden?’ Mike asked him. ‘That’s what we don’t understand. Why now as opposed to after the actual hearing. What’s prompted it?’

He was getting to the nub of it. There must be a reason. What had they discovered, bar the lice and the stench and the obvious dishevelment, that would prompt them to take the kids so suddenly?

Anna answered. ‘Like Robert said, the situation’s just deteriorated. And despite several warnings, the mother’s not turned things around. We simply couldn’t leave them, that was all. She’s not been feeding them, washing them, washing their clothes – stuff like that, mainly. And they’ve been eating out of dustbins and stealing food from other children’s lunchboxes in school. We just had to act, basically … well, you’ve seen for yourselves now, of course.’

I glanced towards the living room. ‘Those poor, wretched kids,’ I said. ‘They just look so sad and scared. This must be awful for them.’

‘It has been. It is. It was really traumatic taking them.’ I saw the anguish in her expression and I believed her. This was probably the least edifying part of her job. No, more than that – it must have been grim for her. ‘They were clinging to their mum,’ she said. ‘Screaming at her to stop us. To help them. Really upsetting …’

She tailed off, and I could see it was upsetting her now. ‘So what about their stuff?’ I asked briskly, to change both the tone and the subject. ‘They don’t seem to have much, even by these kinds of standards.’

‘That’s it,’ Anna said. ‘They have nothing. Literally nothing.’ She nodded towards the hall. ‘I helped pack, so I can tell you, there’s nothing of use in there. Couple of sets of disgusting pyjamas, a couple of raggy hoodies and T-shirts – very little else.’

I could feel a wave of sadness wash over the table. Poor, poor children. What desperate straits to be born into.

‘So,’ Mike said, trying, as I had, to lift the tone again, ‘anything else useful you can tell us?

‘Well, just about their medication, really,’ Anna answered. ‘We’ll obviously sort everything out paperwork-wise, when we have the pre –’ she smiled ruefully. ‘Ahem, pre-placement meeting. But in the meantime –’

‘Medication?’ I asked. ‘What medication?’ This was news to both of us and it filled me with dismay. Sophia, our last child, had had a rare disorder called Addison’s disease, and along with all her other problems, the illness had caused many, many more, as we struggled with a regime of careful nutrition and daily meds, any wobble in which could potentially make her seriously ill. And had done, more than once. I shuddered to recall the stress of it. And now again. What on earth was wrong with these ones?

‘Oh,’ Anna said, colouring slightly. ‘Did John not explain? Or maybe I forgot to explain to him. Both the kids have been diagnosed as having a form of ADHD. They are absolutely fine on their Ritalin,’ she was quick to reassure me. ‘And they’ve both had it for today, so you don’t need to worry. In fact, it’s nothing to worry about in any case, really. Just a tablet each morning and that’s all there is to it. They do have a specialist they’re under, of course, but they’ll be here so short a time that it’s not going to be relevant to you. Just a tablet a day, and that’s it sorted.’

That the children had ADHD – attention deficit hyperactivity disorder – wasn’t really much of a surprise to me. As a behaviour manager in the local comprehensive I’d dealt with plenty of kids in school who were similarly afflicted, and was familiar with the condition and its symptoms, not to mention the action of Ritalin on them – that ‘zombie’-type demeanour the drugs seemed to make them have. But, yes, compared to Sophia’s Addison’s disease, this was mild. But I felt my hackles rise, even so. Not relevant to me? Of course it was relevant, I thought, you silly woman! And fancy just springing something like that on us at the last minute. Did she really forget before? I was doubtful.

‘Okay,’ I said pointedly, ‘but is there anything else we should know?’

‘Not really,’ she said, seemingly oblivious to my slightly chippy tone. ‘Like I was saying, we’ll be here the same time tomorrow for what should have been the pre-placement planning. I’ll bring all the paperwork, of course and – oh, in the meantime, my boss asked me if I’d give you this.’

She reached into her bag and pulled out a white envelope which, when I opened it, turned out to be stuffed with ten-pound notes.

‘What on earth’s that?’ asked Mike, seeing it and grinning. ‘Danger money?’

‘It’s two hundred pounds,’ Anna replied, her own smile somewhat sheepish. ‘I know it’s a bit irregular, but you’re to spend it as you see fit. You know – get anything you think the children need. We’re well aware how much stuff you’re going to need to get for them, even if it is for a very short while.’

Very irregular, I thought as I pushed back the flap. And it was. The normal procedure was that we’d buy anything our foster children needed, then put in the receipts and justify – very robustly – why we’d needed to spend the money. It would invariably be weeks and sometimes months before we saw it back in our bank account. Yes, this was odd indeed. And it made us both wonder. Why exactly were they trying to butter us up so much? Were they that worried we’d change our minds and reject them?

They needn’t have worried. While the social workers said their goodbyes to the children, I took a quick peek at the sorry pile of belongings in the hall. Anna had been right. In the case there were indeed two pairs of manky, torn pyjamas, jumbled up with a couple of T-shirts, the colour of dirty washing-up water, and a couple of broken photo frames, containing pictures of, presumably, their mum, dad and what looked like all five siblings together. In the bin bag there was very little more. A couple more items of clothing that I wouldn’t even have used as rags to clean my kitchen floor, an empty baby’s feeding bottle and a large undressed doll. It looked like it should have belonged to the bad boy in the Toy Story movie; faintly sinister, with half-shorn, matted hair, missing eyeballs and scribbles of ballpoint pen all over its face and body.

‘That’s Olivia’s,’ Robert whispered, as he emerged from the living room. ‘Loves that doll, apparently. Dad got it for her when she was four. Only toy she has. The other one has nothing.’

‘Literally?’

‘Yes,’ he said, frowning at me. ‘Literally.’

I put the dolly carefully back in the dusty bag. There could hardly have been a more apt metaphor, I thought. And in every sense, as we were soon to find out.