Читать книгу Runaway Girl: A beautiful girl. Trafficked for sex. Is there nowhere to hide? - Casey Watson, Casey Watson - Страница 9

Chapter 2

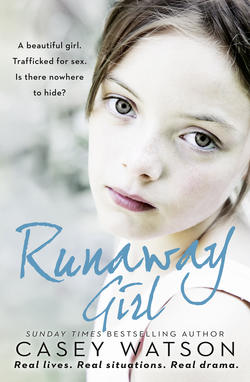

ОглавлениеThe first thing I noticed about Adrianna was her hair. There was so much of it that it would have been impossible not to notice it: thick and wavy, it was the colour of a church pew or polished table and, though it was clearly in need of a good wash and brush, it was the sort of hair my mum would have called her ‘crowning glory’. And it was long, falling down to her waist.

She was tall too – as girls often are at that age. A lot taller than I was – which wasn’t hard, admittedly. She was also painfully skinny, but though she looked exhausted and in need of a good meal, there was no denying her natural beauty.

‘Come in, come in,’ I urged, gesturing with my hand that she should do so, trying to reassure her, despite knowing that there was little I could say – in any language – that would make her less terrified than she so obviously was. Not yet, anyway. I knew she was a child still but I doubted there was a person of any age who’d find anything about her current situation easy.

In common with so many of the children Mike and I took in, Adrianna had arrived with barely anything. She had a small and obviously very old leather handbag, the strap for which she held protectively, like a shield. Other than the bag – and it could have barely housed more than a purse and passport – she appeared only to have the clothes she stood up in. A pair of sturdy boots – again, elderly – and of a Doc Martens persuasion, a long corduroy skirt in a deep berry shade, a roll-neck black jumper and a leather biker jacket, which, once again, had clearly seen better days.

And all of it just that little bit too big for her. So, on the face of it she should have looked like the refugee she purported to be, but instead she had the bearing and grace of a model. It was only her eyes that betrayed her anxiety and desperation. I found myself wondering two things – first, when she might have last had a bath or a shower, and second, what kind of background she had come from. Bedraggled as she was, I knew that those boots and that jacket wouldn’t have been cheap.

‘So,’ said John, herding her in but never quite making contact – I sensed a strong reluctance on his part to try to baby her too much. ‘No luck with an interpreter, so we’re just going to have to make the best of it tonight, I’m afraid. I’ve left a message with head office and made it clear that it’s urgent, so hopefully we’ll have better luck getting hold of someone tomorrow morning. In the meantime –’

‘In the meantime, you look frozen,’ I said to Adrianna, grabbing her free hand impulsively and seeing the fear widen her eyes. I let her go again, smiling, trying to keep reassuring her. ‘Look at you,’ I said again, now rubbing my hands up and down my own arms. ‘A hot drink, I think. Coffee? Kawa? Tea?’

‘Kawa, dzieki. Dzieki,’ she answered.

‘Thank you,’ said Tyler, who was standing with Mike behind me. ‘Dzieki means thank you,’ he explained, smiling shyly. And he was rewarded by the ghost of a smile in return.

I took her hand again and this time I grasped it more firmly. ‘You’re welcome,’ I said, squeezing it to underline my words.

‘Dzieki,’ she said again, her eyes glinting with tears now. ‘Dzieki. Dzieki. Dzieki.’

In the event, there was no need for an extended session of complicated, halting, hand-gesture conversation because all Adrianna wanted to do was go to bed. Once she’d gulped down her coffee – and she really did gulp it – she almost bit my hand off when I gestured we might go upstairs.

And I understood that. I had no idea how far she’d travelled or what sort of trauma she’d run away from, but the need to shut the world out is a universal one.

‘So, this is the bathroom,’ I explained needlessly once we’d arrived on the landing, leaving Mike and John downstairs to deal with the paperwork. Tyler, too, seemed to understand he’d be better off leaving us to it. Having exhausted the little stock of useful Polish that he knew, he’d quickly announced he was off to spend some time on Google Translate and disappeared into his own bedroom.

‘Make yourself at home,’ I said to Adrianna, gesturing again, this time towards the bottles of shower gel and shampoo. ‘Have a bath, if you want. I’ve sorted out some clean nightclothes and put them on your bed …’

To which the same response came – dzieki, dzieki. She didn’t seem to want to attempt to say anything else.

‘So, anyway, your bedroom …’ I began, stepping back out, assuming she’d follow me, but no sooner had I left the bathroom than she had her hand on the door.

‘Prosze,’ she said. ‘Prosze?’ She frowned and bobbed slightly. A brief knock-kneed curtsey, accompanied by a grimace.

I grinned, the penny dropping. And then the thought of the word ‘penny’ made my grin turn to a chuckle. Some things were the same in any language.

Back downstairs I joined John and Mike at the dining table, the piece of furniture across which so many similar discussions had taken place over the years, and so many pieces of paper shunted back and forth for signing – the placement plans, the risk assessments, the parental consent forms, to name but a few. Though, on some occasions, this one included, the paperwork was secondary – the main aim was to find a home, and fast.

Because Adrianna had come to us as an emergency placement, there was no care plan yet in place for her, of course. Or, indeed, a social worker allocated to her. We were just, as John had already told us, a place of safety for her to be billeted at while investigations were made into her situation – for which we’d obviously need that interpreter – and the circumstances that had brought her to us. As a 14-year-old there was no question of her going to supported lodgings placement; she needed full-time carers, as well as an education. Not to mention health care, which would obviously include a doctor and a dentist, as well as access to an optician and a school nurse. These things were standard in the UK, of course, but I knew nothing of the system from which Adrianna had come.

All this, however, was to be arranged down the line. In the short term we urgently needed an interpreter, which, once the little paperwork we could deal with was quickly dispatched, John promised he would return with the following morning.

‘Well, in theory,’ he said, as he put his papers away and prepared to leave us. ‘It’s just occurred to me that our usual woman is away on holiday, so it might prove to be much easier said than actually done. If so, I guess it’s going to have to be Google Translate!’

In the end it wasn’t necessary for us to break out the laptop, because just as he’d hoped, John was back with an interpreter the following morning, just after Tyler – much disgruntled – had already left for school. He’d already, it seemed, taken quite a shine to our latest family member, and was disappointed that I hadn’t dragged her from her bed before he went.

And ‘dragged’ was the operative word. I showed the men into the usual seats around the dining table then hotfooted it upstairs to wake Adrianna before making coffee, thankful for the ten-minute warning John had texted (which had at least given me time to dress), having the previous evening told me they’d be coming around ten.

And, boy, she took some waking. With the curtains shut tight, and her burrowed completely under the duvet, it was like walking into a tomb. And when she did wake and I explained they’d come earlier than expected, she showed zero enthusiasm for getting up and meeting her new interrogator, even when I indicated that she could do so in her dressing gown, not least because 8.45 a.m. was a very teenager-unfriendly time of day at the best of times. And these were definitely not the best of times.

I couldn’t say I blamed her. Though I didn’t yet know how long she’d been sleeping rough (something, among many other things, that I now aimed to find out), there was still the small matter that she’d travelled several hundred miles the previous day, was unwell, among strangers, and with her future uncertain. I think I’d have preferred to stay in bed as well.

‘I’m sorry,’ John said, as I returned to the dining room and promised that Adrianna would be down shortly. ‘It’s just that Mr Kanski here is on a tight schedule today and it was a question of making hay while the sun shone.’

‘That’s fine,’ I reassured him. ‘What would you both like to drink?’

‘Er, nothing,’ John answered, glancing at the other man before speaking. ‘Tight for time, as I say …’

‘Up to you,’ I said. ‘But I’m having one. It won’t take long, and –’ I indicated upstairs with a nod.

But the man shook his head. ‘No, thanks all the same,’ he answered stiffly.

I went out into the kitchen, catching John’s eye as I left. Looking at Mr Kanski, I’d had that thing happen. That thing – thankfully it only happens to me rarely – where a person does something – some small thing; it’s often not a big thing – to make you form an unfavourable first impression. There was nothing about Mr Kanski that I could really put my finger on. He was the sort of unremarkable, soberly dressed man I’d half-expected. Late thirties, perhaps, or early forties. The sort of person who wouldn’t really make any sort of impression if they were sitting beside you on a bus. But there was something that set my teeth on edge about him nevertheless. He wasn’t exactly impolite but then he wasn’t exactly on the same page as me either. I got no sense that Adrianna’s desperate circumstances particularly moved him, even though I felt absolutely sure John would have conveyed the distressing nature of them to him on the way here. Plus there was this sense I had – strongly – that some words had been exchanged between them. That ‘fitting us in’ was some major inconvenience.

As well it might be, I thought, as I popped my head out of the kitchen door and hollered ‘Adrianna, how are you doing?’ up the stairs. I did it as much for the man’s benefit as anything. It might well be that he had much bigger translation fish to fry and that coming to chat to our 14-year-old runaway was indeed a bit of a pain.

Even so it rankled and, as I came out of the kitchen to see Adrianna starting down the stairs, I nodded towards the living-room door and pulled a conspirator’s face – just a very slight one – to let her know he seemed a grumpy old sod.

Of course, what Adrianna made of all my gurning could only be guessed at, but it was an irrelevance in any case, because as soon as we all gathered at the table I could see, just by her body language, that she felt the same about him as I did.

And she dealt with it in the traditional teenagerly way, by switching off. You could almost hear the click. And what she started with her expression, she finished with her body language; she didn’t so much sit, as slither down into the dining chair, sitting back, looking across the table with tired, wary eyes. Quite apart from anything else, she looked ill. Definitely as if she was still running a temperature, and I had to fight an impulse to reach across and place the flat of my hand against her head. Perhaps having the man round for an interrogation so soon wasn’t a very good idea. It wasn’t as if there was some huge rush to all this, after all. It wasn’t like anybody was going anywhere.

John cleared his throat and adjusted his tie. ‘Adrianna, this is Mr Kanski,’ he explained, a little over-brightly. ‘He’s come to help with the translation of our conversation.’ And as if via autocue, because I didn’t see any sort of sign pass between them, Mr Kanski duly translated what he said. I had to admit, he seemed good at it.

‘So,’ John continued, ‘we need to find out a little more about you, Adrianna. Then we will know how best to help you. Is that okay?’

The man began translating this as well, and, seeing Adrianna’s glazed expression, I decided to help things along a bit by getting her some pills.

‘Sorry,’ I said, as he glanced irritably at me, ‘I just want to pop into the kitchen and grab Adrianna some water and paracetamol. She’s not very well,’ I added, looking at Mr Kanski. He nodded. ‘But please feel free to carry on without me,’ I added. ‘I’m aware that time’s an issue.’

Smiling politely, I then got up and left the room.

I was gone no time at all – couldn’t have been much more than a couple of minutes – but by the time I returned John had already scribbled a fair bit on his pad. I couldn’t see what, but as I put the tablets and water in front of Adrianna I could sense a definite tension in the room.

The translator was speaking again, obviously reiterating some lengthy question John had put to her while I was in the kitchen, and as he spoke I could see Adrianna already forming a head shake. And then another. Then a shoulder shrug and spread of her palms.

‘Nie,’ she said. Followed by an indecipherable longer utterance.

‘She says she has no family to go back to,’ the man said. ‘She said she is an orphan. She says she doesn’t know when or where she entered the UK.’

‘No family at all?’ John asked. ‘Was she brought up in care, then?’

The man asked her. Again, no. ‘She says a children’s home. In Krakow. Which she ran away from.’

I looked across at Adrianna. Despite the direness of her straits and her obvious infection, one thing I’d noticed straight away was her unmistakable sense of self. Her self-possession. Her bearing. This was a child raised in the care system? It didn’t seem to fit. I knew they came in all shapes and sizes – as did all kids – but there was always this look they had; of being beaten down, diminished. Faintly hostile. Assessing. Adrianna just didn’t. She just didn’t look like a looked-after child. ‘So no family whatsoever?’ I asked, looking quizzically at her.

Mr Kanski asked the question again. Adrianna looked right back at me as she answered. And provided another ‘Nie’.

‘So how about your time in the UK?’ John continued, with his pen poised over a pad, ready to spring into action. ‘Can you tell me more about that? What have you been doing? How have you been living? With friends? On the streets? Have you been staying in any hostels? Have you had any contact with social services, or the housing office, there?’

Adrianna listened, seemingly intently, because she sat slightly forwards as Mr Kanski conveyed all this. Then she responded with another lengthy stream of Polish. But even as she spoke I knew we were making little in the way of progress. It was just so obvious, from her tone, from the lack of place names, from the wealth of ‘ums’ and ‘ers’ and shrugs, so when Mr Kanski explained that she’d been ‘getting by’, living on friends’ floors and couldn’t remember any details about anywhere she’d been staying as she’d always ‘moved around a lot’, it came as no sort of surprise. She clearly wanted to tell us as little as possible.

‘What friends?’ I asked. ‘Are there friends who’ll be wondering where you are now, Adrianna?’ I asked, speaking directly to her.

‘No one,’ came Mr Kanski’s answer, in translation of yet another flat ‘Nie’.

‘What about London, Adrianna? Where you’ve just come from? How long were you there?’ John asked. ‘You were there for a bit, weren’t you? Before you arrived in Hull?’

‘About a month, she thinks,’ Mr Kanski said, once he’d asked the question and been given the answer. ‘Though, I think –’

‘Casey?’ Adrianna’s voice. Small but decisive. ‘I not so good.’ She gestured to her head and grimaced at me. ‘Ill.’

And to be fair, she certainly looked it. Her face was pale and clammy and her hair was sticking to her forehead. ‘You know what?’ I said to John. ‘I think we should hold off doing this until Adrianna’s feeling a little better, don’t you? Come on, love,’ I said, rising from my seat and gesturing that she should also. ‘Back to bed with you.’ I turned to John. ‘We can just as easily have this conversation in a few days, can’t we? And with Mr Kanski in a hurry to be somewhere anyway, perhaps that’s best, eh? I’m sure we’ll be able to get more out of her once she’s properly rested and feeling brighter …’ I moved aside to let Adrianna pass me. She even smelt unwell. Not as in body odour particularly. Just that slightly rank, sick-roomy smell. ‘Off you go, sweetheart,’ I said gently. ‘Oh, and take your water with you. I’ll be up to see how you’re doing in a bit, okay?’

‘Dzieki,’ she said. ‘Dzieke.’ Then she was gone from the room.

Both men watched her leave, though with different expressions. I got the feeling that Mr Kanski was only a whisker short of huffing about being dragged round in the first place. ‘Well, we tried,’ John said, clicking his ballpoint and putting his pad away. ‘But you’re right, Casey. Best we leave all this for a bit, I think. If you’re happy to hang on to her, that is.’

I rolled my eyes at him. ‘You know I am, John. Don’t be silly. Anyway,’ I said, eyeing the pad that was disappearing back into his briefcase, ‘what did you manage to get? You know, while I was out in the kitchen.’

‘Nothing,’ he said. ‘She’s proving to be a dark horse, this one, isn’t she?’

Mr Kanski kind of rustled. John noted it. ‘And thanks so much for coming at such short notice, Robert,’ he said to the other man. ‘It really is much appreciated, even if we didn’t manage to get very far.’

‘Which is understandable,’ I added. ‘I should really have called you and stopped you coming. I would have, had I realised soon enough. She’s clearly got some sort of virus, bless her …’

Which was when I got that sense of it again with Mr Kanski. Just a slight tweak in expression, the sense of words thought but unspoken. ‘Well, that may be so,’ he said, glancing at me through narrowed eyes. ‘But she’s lying through her teeth.’ He smiled a grim, humourless smile, which included both of us. ‘But I imagine you already knew that.’ He put a fist to his mouth and cleared his throat. ‘Anyway, nothing unusual there, eh?’

He checked the clock on his mobile, then slipped it into his coat pocket. ‘Shall we, John?’

It was awkward, and strange, and I pondered it as I saw them out. Even with John’s light-hearted, even jocular ‘You got it – in our line of work that’s pretty much a given!’ there was something. Like there was something we didn’t know about him.

‘You know what? I should invite Vlad to tea tomorrow, shouldn’t I?’ Tyler, home from school and football practice, had obviously been giving the language barrier serious thought. ‘I was thinking it would probably be better – you know, like in she might open up more, if she could speak to someone Polish who’s her own age. Not some old, disapproving crusty,’ he added, causing me to stifle a chuckle. I had, of course, filled him in as much as was appropriate. Perhaps too much, I decided, pressing the chuckle down.

‘You know, that isn’t a bad idea,’ Mike said, holding his hands out for Tyler’s filthy football boots. One of my most favourite rituals in a relationship that seemed to thrive on them was Mike’s undying devotion to cleaning Tyler’s muddy boots. It was a kind of symbiosis, even – it meant Tyler felt loved and cared for (which he was) and also filled the Kieron’s-football-boot-shaped hole in Mike’s life. On such seemingly small things are great strides so often made.

‘I know,’ Tyler said. ‘And he’s stoked about meeting her. Shall I text him?’

‘Hold your horses, love,’ I cautioned. ‘Let’s be sensible. One, she’s not well – and it’s probably contagious – and two, she might not be quite up to meeting Vlad yet.’ I spoke with feeling, Vlad being one of the more memorable of Tyler’s friends. He was a big lad, in all ways – he had a big personality, and also found it difficult to cross a room without knocking something over. Not so much uncoordinated as a force of nature, barely contained. ‘Tell you what. Keep him on standby. Tell him we’d love to have him over, but that we’ll hold off till next week, when whatever this bug is has run its course. Which I’m sure it will.’

Mike ran a hand over his throat. ‘Hmm. If we’re lucky.’

And we were lucky – well, in the short term, as whatever it was didn’t seem to touch us. But Adrianna herself continued to be really poorly. She spent the remainder of Wednesday in bed – only surfacing to sit with us in the living room to watch David Attenborough for an hour that evening, and barely got out of it at all on Thursday.

‘You know what I’m going to do?’ I said to Mike before he left for work on Friday morning. ‘I’m going to call the GP surgery and see if I can get a home visit. I think she’s poorly. As in sick. With a virus or something. Which I know he won’t be able to help with,’ I added, before Mike could. (He was something of a pedant when it came to people going to doctors when they had viruses, having seen a programme on telly about how the over-prescription of antibiotics was causing all the terrifying superbugs in the world.) ‘I just think it wouldn’t hurt for her to have a bit of a once-over, would it? Specially if she’s been sleeping rough for a while. And she’s so thin. And let’s face it, we don’t know the first thing about what she’s been up to or who she’s been with. She could have anything wrong with her, couldn’t she?’

‘No, I think that’s a good idea, love,’ he said. ‘Put our minds at rest, too. We can’t just keep feeding her paracetamols, can we? She needs to be up and eating. Can’t be doing her any good, being holed up in that bedroom morning, noon and night, can it?’

Which sentiment I agreed with, even given the usual teenage propensity for sleeping the day away. Adrianna, however, seemed to have other ideas.

‘No, no. Am ok-ay,’ she assured me when I went up to suggest it mid-morning, Tyler having long since left for school. ‘Am ok-ay. No problem.’ She rubbed sleep out of her eyes. ‘Please. No doctor.’

But there was no dissuading me, not least because of the uneaten sandwich from the previous evening currently curling on the bedside table, the sheen of sweat on her brow and the faint but still palpable smell in the room. It wasn’t exactly fetid, in the usual teenage-boy’s-trainer-pile kind of way. Just distinctive and familiar. A smell every mother learns to recognise. The smell of sick child. Of fever and sweat – of malaise.

And something else. Something familiar but which I couldn’t quite put my finger on. A sweetish smell. Odd. Definitely not right. ‘Yes doctor,’ I said firmly, picking up the plate and the empty mug beside it. If there was one thing she could clearly stomach, it was coffee. ‘Just to check you are okay,’ I added gently. At which she pushed back the duvet.

‘I get up,’ she said. ‘Am okay. See? No doctor. I have bat?’

It took me a second. Then she pointed towards the bathroom and I realised. ‘Bath?’

She swung her legs out of bed and stood up, her pale feet looking stark against the hot pink of her pyjama bottoms. ‘Bath,’ she confirmed, nodding. ‘I have bath. Am okay, Casey. No doctor.’

I stood aside so she could pluck her fleecy dressing gown – formerly Riley’s – from the back of the dressing-table chair. ‘I don’t know, love …’ I began, my mind now filling with a whole new set of questions. Why the great reluctance to see a doctor? What did she imagine he’d do to her? Was it a reticence born out of fear of further questioning by someone in authority? She was clearly terrified of being sent away again, after all. Or did she have something else to hide – something physical, that she didn’t want him to see? Scarring, perhaps? Bruising? I couldn’t help but wonder because, these days, such thoughts kicked in so automatically; I’d seen so many damaged children – as in burned, battered and beaten – that now it was an instant response in me. Where had she come from? Had she perhaps been abused?

‘Dzieki,’ she said, as she hurried across the landing and went into the bathroom.

‘Adrianna!’ I called before she slammed the door. I’d just had another thought and slipped into the bathroom as she stood there looking surprised. I opened the bathroom cabinet and gestured with my hand that she should look, so that she could see I had a stock of sanitary protection in there, just in case. I could have kicked myself – perhaps that was all it was after all. She was the right age, and if I remembered correctly, Riley had suffered terribly with her periods as a young teenager – cramps, fatigue and a roaring temperature. Why hadn’t that occurred to me before now?

I went downstairs and called the doctor anyway.