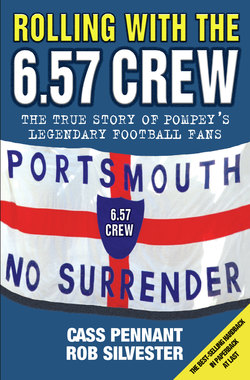

Читать книгу Rolling with the 6.57 Crew - The True Story of Pompey's Legendary Football Fans - Cass Pennant - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Introduction

ОглавлениеPortsea Island, which the city of Portsmouth sits on, is one of the most densely populated areas in Europe. Rows and rows of rabbit hutches were crammed closely together to provide the working class with cheap housing. In days gone by the city was a living hell as press gang fought press gang on the streets of Old Portsmouth, while vice and crime flourished among the impoverished. Many a conflict has been launched from Portsmouth: Agincourt, D-Day, the Falklands and Trafalgar have all used our city as a launch pad for famous and glorious battles. The city, on these historic occasions, has been awash with patriotism and pride.

After its pounding by the Luftwaffe in the forties, Portsmouth was re-built into a concrete jungle of council estates, re-housing ex-servicemen and their families who chose to settle here. After much neglect and a lack of investment, these areas of false hope quickly became downtrodden and breeding grounds for the hard-working labour class of the city. The mass of tower blocks that sprang up out of old bombsites spawned generations of kids who had nothing but a bleak future to look forward to.

There is no easy answer to why football violence was so prevalent in Portsmouth. Other cities with a higher population and just as many deprived areas have not had as many active thugs hell bent on causing trouble at games. People reading this book may ask, Why did they do it? What was the point? What prompted a bunch of mostly kids to roam the country looking for a fight? What end did it serve? It could be argued that it was one of the first generations of working-class men to be untouched by a major war. It could also be said that the parallels between the violence and the ‘no society, start of individualism’ philosophy of Thatcher contributed to it. Also, the growing number of unemployed in the ever-declining economy could not have helped. These factors may have contributed but for those who were there it was all about the buzz and the surge of adrenalin only felt when the familiar roar went up and the whites of the opposition’s eyes were just a punch away.

The recollections in this book of the main faces of the 6.57 will take readers through these violent and sometimes humorous events. The government always had tough words for such ‘terrible displays of violence’, but would have used this aggression to its own advantage had a conflict where conscription was necessary presented itself. Who have always been at the forefront of every battle? The upper and middle classes have historically led from behind the front line. Well behind it. It’s the working class who fight the battles, yet apparently they must have the permission of the ruling classes to vent this aggression. A case of you can only be violent if we want you to and it suits our needs, otherwise be passive and put up with being downtrodden. Aggression usually stems from a person’s way of life and upbringing. It is the effect of a cause. If the government creates an underclass of people with low-paid jobs and no self-respect, then places them in cheap housing, it is obvious that the youth of these areas will revolt.

The violence on the terraces spiralled across the country following the riots in most cities in 1981. The country’s youth felt isolated and disenfranchised. The incidents of the eighties were widespread and frequent, with the violence of the era getting intense and out of hand. The numbers seemed to increase with every game and the authorities knew something had to be done to combat it. They had mistakenly thought that the 6.57 Crew had become organised, as rival mobs fought out battles dressed in fashionable sportswear and expensive clothing with pinpoint timing and military-style precision. As usual, they were way off the mark. The 6.57 Crew was about as organised as the proverbial brewery piss-up. The closest we got to organisation in the early days was ‘see you in Punch and Judy’s after the game’ or ‘meet you at Portsmouth and Southsea at half-six Saturday morning’.

Portsmouth is not a place of many shootings or organised crime. It is very contained and rather small for the number of people who live in it. The police were on top of most of the illegal activities that went on but football was one boil they just could not lance. And it really grated on them. The Old Bill like to drum up sinister and budget-justifying reasons to target certain groups and they used the 6.57 as a scapegoat for every fight in and around Portsmouth for years. Some justified. Some not. The 6.57 were even accused of having ranks and generals and soldiers. Absolute nonsense. Every group of human beings has people that take control and that the others listen to: born leaders who led from the front. But there were no ranks. The police spotters loved the name 6.57, from the days of King and Hiscock right up to the budget-wasting overkill of HOOF. The media love a sensation and cover soccer violence thoroughly. It makes good press to have these almost mythical type gangs with sinister overtones roaming our vulnerable streets picking off innocent football fans. As every thug across the country knows, this rarely happens. Like-minded people met like-minded people to have a fight. That’s all.

The 6.57am train to Waterloo is the earliest train you can catch to the capital and gives you the flexibility to be almost anywhere in the country by no later than one o’clock. This was great for us as it got us into enemy territory as early as possible and we could set about causing maximum mayhem. It has to be said, though, at the time when casual dressing and weekly rumbles were at their most active we did not really call ourselves any name. At the time, we just thought ourselves game fellas up for a row.

The name 6.57 has been slowly accepted and has gone into folklore status subconsciously and was never more prominent than when Docker Hughes was running for Parliament and the crew got national coverage. The branding of our gang was an eighties thing. It was all the rage in that decade to have a name and most of the top firms went by some moniker. But that is taking nothing away from the achievements around England of the original Pompey Skins and seventies-style boot boys. This book deals predominantly with the Air Balloon crew, one of the many and probably the largest firms in the city. They were into everything: football, fighting, the casual movement, thieving and drugs. All round anarchy. And all this at 100 miles an hour. Also the Eastney lot are covered. They were a more serious-minded crew but really tough with it and would always stand their ground. The boys from Somers Town and Paulsgrove and many others integrated well and could be usually found on a Friday night drinking in the Air Balloon with the Stamshaw boys.

The people who are categorised as the 6.57 are mainly town boys, but there are some from outside the city limits who ran with the top firm. But they were just as active. Some of their escapades are unbelievable. A book could be written about their exploits alone and it would make a cracking read. It was always a good blend of people and the amount of nutters on the firm were too numerous to mention. Solo attacks have been frequent. In one famous incident one of the chaps jumped into an end full of Boro on his own after scaling a huge fence, which they still talk about up there to this day. Another windmilled into a side full of Cardiff and two well-known faces were dragged out of the Leeds end before they were torn apart. We at Pompey have the same legendary moments to share that every major firm in the country has.

The times we had together and the feeling of camaraderie and unity are unparalleled by anything else those involved have ever felt. If you were a hardcore member of your particular firm you will know what I mean. To be in battle with your pals can be an uplifting thrill and highly addictive. The aftermath and buzz of a major punch-up was hard to beat as everyone swapped stories still rushing on the high. Feeling danger with someone else and knowing that you could count on their support should events go wrong forges strong and unbreakable bonds. Though obviously not at the same level, those involved in the violence can relate to the old war chums who still meet up every year and shed a tear for fallen comrades.

You will read about the country’s major firms, also a few surprises will be thrown into the mix. We have played in all the divisions in the last 30 years and would pull 30,000 crowds in the old fourth division. But make no mistake about it we are THE football fans of the South. If you believe what you read on the internet you would think that the idiots up the road used to trade blows toe to toe with us, sometimes coming on top, sometimes not. It is pure fantasy. We do not respect them at all, and have never really had it properly with them. We would have loved to have had a major crew just up the road. We were hell bent on violence in those days and a Millwall or Cardiff, 16 miles away would have been heaven. This so-called rivalry is pure geography. If Bournemouth were closer they would be the team vilified. If Southampton had a major crew as active as ours then there should be countless stories of battles between us. There are none. They are not in our league as a football firm and everyone knows it. They never get mentioned in any book about football violence and they only get a mention in this one so we can put the record straight in print once and for all.

However, there is plenty of stuff to read on the top crews we have encountered, and also the nutty little firms at the likes of Lincoln and Hartlepool. We have been just about everywhere and had mixed results in battle, but it is from the lower divisions that some of the best memories come. The reader of this book will be taken on a rollercoaster ride of violence, adrenalin, laughter and excitement, with humour unearthed at the most unexpected of times.

Follow the journey through the golden era of the Original Skins of the Golden Bell Pub, where heady nights on Dexy’s and mandrix were followed on by the next day’s outing on the terraces. Then the crazy lawless days of the seventies and taking the opposition’s end on match days decked out in three-star jumpers, Anco Skinners and knee-high Docs are covered in detail. Also the times when the Bovver and boot boys ran riot all over the country. Classic encounters like the storming of the Grange at Ninian Park in 1973, right through to Pompey Animals at Reading in ’77 and then to the heady days of the 6.57 in the early eighties. There is also an in-depth chapter on how drugs invaded the top firms in the country, doing what no police tactic could do – quell the violence.

Forget all your current so-called firms, this is when it really went off and violence was proper. There were no surveillance cameras or technology dedicated to stopping it, the fighting was long and fierce and reputations were earned the hard way.

The first-hand accounts which follow are given by Pompey boys from all eras. You know who you are and which are your stories. Thanks for sharing them with me. For clarity, the fans’ first-hand accounts are in italics.

This book is dedicated to all our boys, past, present and future. To the best days of our lives. Play Up Pompey.

Rob Silvester