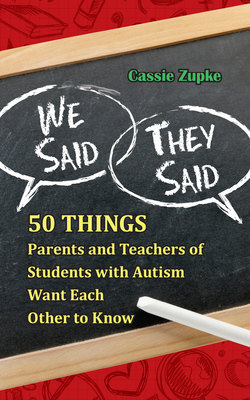

Читать книгу We Said, They Said - Cassie Zupke - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавление

In my role as the founder and director of a nonprofit organization that provides education and support for students with mild autism, as well as their parents and educators, I've talked to a lot of people. I've been a mentor and a trainer. I've attended meetings, given presentations, reassured parents and teachers, advocated for children, helped to dry tears, and offered more advice than was probably wanted. I've initiated programs and later thrown some of them out to build better ones. Over the years, I've worked with hundreds of families and educators. This book represents the summation of what they've talked to me about—their fears, their concerns, and their passions—the things that drive them when they sit down at the meeting table and decide how they're going to help a child.

These are the things they argue about.

Often, these issues are not mentioned in meetings. They are feelings that are discussed only among other parents or only between teachers. Some of the feelings are private. We would never admit them out loud for fear of the judgments that would come down on us. Some of them are buried so deep within us that we don't even know we have them, even though they show in our actions and in the stories we tell.

This book is not a manual about how parents and teachers should be. It's about how we are—our faults and frailties, along with our strengths and passions. Should we feel the way we sometimes feel? No, but we do anyway. It's human nature. The sooner we learn to accept the way we are, the sooner we can get past our conflicts to help our children.

In this book, I assume that everyone involved—parents, teachers, and administrators—are compassionate, skilled, and rational people who are working for the benefit of the child. You and I know that's not always the case. Most people are wonderful and dedicated to helping the children in their care, but there are a handful of folks out there who aren't really up to the job. They may not have good coping skills, they may not care about children, they may be downright mean, or they may have challenges of their own. These people are rare, but they're around.

All the books in the world won't change that, and, unfortunately, mine won't either. But, this book does explain why many people do what they do when they're put in the situation of having to raise or teach a child with special needs. I hope it provides the information you need the next time you're looking for a way to help a child you care about.

Since this book is a distillation of what hundreds of parents and teachers have discussed with me, it describes emotions that most of us feel at one time or another. None of us feels all of these things all the time. I don't know how we'd make it if we did. Each of us has faced and overcome some of these issues, and circumstances may force us to face them again. The best thing we can do is to hold hands and help each other through the hard times.

The people I've worked with care for children with autism, but their stories are common to most special-needs families and their teachers. Raising and teaching kids with special needs can be difficult. It can be stressful, frustrating, and very isolating. It feels like there is never enough information or support. The fact that we care so much for our children makes our struggles more profound, but when we succeed, it makes our children's victories so much sweeter. Our kids are worth it.

If you are reading this book and you have autism, please know that children do not cause the feelings parents and teachers express here. As parents and educators, we care about our kids. It's what we do. We especially want to help our children with anything that makes their lives more difficult. If it's something we can “fix,” okay. If it feels like we can't fix it, we don't like it. The bigger the problems, the more we want to be able to fix them.

We don't dislike autism, and we don't dislike our children because they have autism. We are concerned for our children's futures and how autism will affect their lives. If we knew today that they would be able to overcome the challenges that autism brings, we would accept autism as easily as we accept our child's hair color. But right now, we don't know that. So we worry, and we feel guilty because we can't make the difficulties go away. That's just the way we are.

Autism is a spectrum disorder, meaning it affects different people to different degrees. Medical and mental health professionals have divided the diagnosis of autism into several “subtypes,” such as high-functioning autism, Rett syndrome, pervasive developmental disorder—not otherwise specified, childhood disintegrative disorder, and classic autism, which is sometimes further subdivided into mild, moderate, or severe categories. Being able to group folks with autism according to the type and severity of their symptoms is helpful to professionals but can sometimes leave parents steaming. Parents may feel that the labels given to their child gloss over their child's unique qualities and could lead educators and medical professionals to treat the label and not the child.

Some people also think that parents who use the term high-functioning autism are saying that their children are “better” than children who are more severely affected by autism. However, that's generally not the case. Parents say their child has high-functioning autism because this term best describes the particular set of difficulties their child has. Severe autism, moderate autism, mild autism, and high-functioning autism may be broad, poorly defined terms, but they give everyone who is familiar with autism a quick snapshot of the types of difficulties and needs that affect the person they describe.

In this book, I use the term autism broadly, but I am very selective in my choice of pronouns. Here, I refer to kids as “he” and teachers as “she,” and the parents I talk about are typically moms. I did this for the sake of simplicity and clarity. It just gets too confusing to have too many pronouns floating around. I know there are many girls with autism. Autism in girls often goes undiagnosed or is underdiagnosed because girls are better than boys at mimicking social interaction. As our knowledge about autism increases, hopefully we'll learn more about how to identify the needs of our girls and how to best help them, too. Also, I know there are many wonderful male teachers out there and a whole lot of very involved dads. Good for you. You're just as important in our children's lives as their female role models. I'm not trying to ignore you or imply that you are less important in any way. I'm just attempting to make this book easier to read.

There are going to be some parents who strongly disagree with some of the things I've written from the teacher's point of view. While most parents of kids with special needs have been treated fairly by the personnel at their school, frankly, there are some who haven't. Those parents tend to have an unfavorable view of teachers and school districts. I can't blame them. I also can't blame teachers who have been verbally or physically assaulted by parents, if they're a little skeptical of what I've written from the parent's viewpoint. That's okay. Everyone has had his or her own experiences, and I'm not doubting any of them.

What I've written here reflects the views and attitudes of the majority of parents and teachers I have dealt with. No matter what you hear in the school's parking lot or lunchroom, remember that unhappy people tend to talk the loudest, and happy people tend to stay quiet. The people you hear from are the ones with complaints. The opinions of people who are content often go unheard until you ask.

It took me several years to gather the information necessary to write this book—and a while longer to figure out how to present it so that it is useful. I hope I've succeeded, and I hope you find something here that makes your next parent-teacher conference go more smoothly.