Читать книгу The Well - Catherine Chanter - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

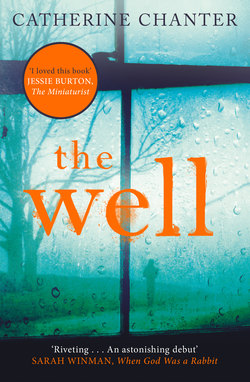

ОглавлениеThe Well has won me back. Tonight will be my first night under house arrest. First of how many? I scarcely dared hope they would allow me to return, yet when it came to the last night in the unit, I clung to the comfort blanket of my sleeping pills and section order, desperate to stay. Security. National security. Secure accommodation. An insecure conviction. It may keep me in, but all the security in the world will not keep the ghosts out; if I am home, they will be also.

In between the nightmares I have been daydreaming my way through three months of enforced idleness: picturing myself escorted from a prison van into the house; running my fingers through the dust on the half-moon table we were given for a wedding present; picking up the photo of the three of us, taken the first day we ever saw the place, me crumbling the damp earth between my fingers and laughing. I thought I might throw open the bedroom windows, listen to the insistent buzzard, stare out over the cracked hills and wonder how it came to this. I thought I would turn on the taps and watch the water stream down the drain, like liquid silver, lost. Things I knew I would not do: pray, write, work the land.

I do not follow that script. In the end, something rather bustling and pragmatic takes over. Maybe it is nerves. I am conscious from the moment that we pull out of the gates that my mouth is dry and I am picking at the sides of my fingernails as I used to when I was a child. I can’t see of course; the windows are blacked out. I wonder if there is a sack under my bench seat, ready to pull over my greying hair and gaunt eyes, just as you see with rapists and paedophiles, when the absence of a face makes them more, not less terrifying, only the hands that strangled the child or the legs that ran down the alley visible to the waiting press.

Are these the palms of a saint or a sinner? I scratch my hands over and over again, hoping they will wake up and tell me.

Even the ruling that I am to be sent back is to be kept sub judice, as they say. I like that phrase. Underneath the justice. If you can only limbo long enough, then the law is upheld and everyone is happy.

‘If we’re prepared to act within the Rapid Processing Regulations, they’ll reach a settlement. All we have to do is withdraw our intent to sue the government for illegal occupation, and then they’ll let you serve out your sentence under house arrest. Deal done.’ That’s what my lawyer told me. I asked him what was in it for the state and he talked about overflowing prisons and adverse publicity, drought and scientific research. I interrupted him, asked what was in it for me. It sounded so simple, his answer.

‘You get to go home to The Well,’ he said.

The first part of the journey from the women’s wing seems slow and takes place against a soundtrack of sirens. Petrol rationing has solved the capital’s traffic problems, but no one seems to have told the traffic lights. Then the feel of the journey changes to the relentless flat, forward impetus of the motorway heading north. I know that route so well and once we exchange the straight line for the swerves and lurches which take you over the hills and down into the valley, my breathing slows and I feel the saliva run again against my sandpaper tongue. Fifteen minutes for the long slow climb past Little Lennisford church; twenty-five minutes before meeting the stretch of flat, straight road beside the poles of the hop fields (the last chance to overtake, as we used to say); forty minutes and the sharp right-hand turn past Martin’s farm, grinding up through the hairpin bends, through the gears, through the clouds as often as not, to the brow of the hill, to the top of the world. Then at last, the swing to the left down the quarter mile of unfenced, rough track which leads through my fields to The Well.

‘Nearly there now.’

The guard’s words are unnecessary.

The van is going too fast for the potholes. Surprising they haven’t done anything about them, but then again, we never got round to it either. It takes the wearing down of water to grind holes in stone and The Well wore her puddles like a badge of honour. We are stopping. The grille is pulled back.

‘We’ll just be a couple of minutes while we check everything. You OK back there?’

It is kind of them to ask, but not clear to me how I am meant to answer. That I am totally at ease with being brought back to my own notorious paradise in a prison van?

‘I’m fine. Thank you.’

I sit very still. Part of me doesn’t trust the ruling even now. Bizarre ideas from old war films tug at the rubber mat under my manacled feet and I see myself taken from the van, led to my dear oak tree and shot there, falling in a crumpled heap among last year’s desiccated acorns and the sheep shit. The soldiers are getting out now, slamming the doors behind them.

‘It’s unbelievable, isn’t it?’ That is the woman with the Birmingham accent. ‘It’s just like they said, just like on the webpage.’

‘What is?’ The driver. I could tell from his choice of music on the journey that he had no insight.

‘This is. It’s like going back three years. Green fields. When did you last see grass like that?’

So, my fields are still green.

New voices. Greetings. Slightly formal. Then a younger man talking.

‘You should talk to the locals. They say it’s true what it said in the papers. When she was here, it rained; when they arrested her, it stopped.’

‘Where did it happen then?’ asks the driver.

‘Down in the woods.’

‘I’m with those who think the old bag’s a witch not a saviour.’

‘Quite a sexy old witch, all the same.’

They must be moving towards the house because I can’t catch the rest of their conversation. The knowledge of the space outside is somehow suffocating me inside and I feel nauseous. Not now, I think. No more of these visions, no more drownings. Sweat breaks out on my forehead; I try to raise my hand to wipe it away, forgetting the weight of the handcuffs. I too am being pulled under the surface. I am not mad. I put my head down between my knees to stop myself fainting and the darkness of the van slowly steadies itself, the thick water recedes and I become myself again, just as the footsteps grow louder on the gravel and the back doors of the van are opened.

‘Home at last!’ she says. ‘Out you get!’

There is no blinding flash of sunlight, rather the washed-out blue of an early April afternoon merges with the bleak interior of the van in the way that paints on a palette mix in water and reach a grey compromise. I try with some difficulty to get out, stooping under the low roof of the van, holding my handcuffed wrists in front of me like some bizarre posture of prayer.

‘Tell you what,’ says Birmingham woman, ‘sit on the edge here and I’ll take those off you. Home sweet home! Hope someone’s done the washing up. That’s all I ever want when I get back in the evening.’ She punches various codes into the keypads attached to my limbs.

The driver has joined us now. ‘Bet you don’t get your lily-white hands all damp and dirty in the sink.’

‘Tell you something, have to now. The dishwasher used to cost a fortune on the water meter. Still, every cloud has a silver lining, as they say, washing up’s about the nearest I get to a bath nowadays.’ She fiddles with my unattractive ankle bracelet. ‘This one stays on, it’s what we call the home tag.’

I am sitting on the edge of the back of the van, childlike, my legs not quite touching the ground, and when I am free, I feel each of my wrists in turn and then stand uncertainly and take a few steps away from the guards. In front of me, the stone front of the house stands even and steady; it is my spirit level. I turn, and then I am facing my fields which rise up and fall away before me, their hedges like ley lines, feeling the contours, the forests like velvet folded into the valleys. A hand takes my elbow. I shake it off, but follow the guard to the front door all the same. We don’t use this door, I am about to say. We use the back door, kicked off our mud-clodded boots on the tiled floor there, once; hung the fishing rods on the hooks above the raincoats there, once. We. Me and Mark. Me and my ex. Front door. Back door. River. Ex. Words.

‘This is as far as it goes for us,’ says the driver. ‘Job done. I expect your new friends will introduce themselves once we’ve signed everything,’ and he waves towards three armed young men in uniform who have appeared at the fence between the house and the orchard and are standing with their backs to us, pointing towards Wales. That was one of the reasons they agreed to house arrest, apparently, the fact that there were government soldiers here already, keeping watch over their crops by night.

‘It must be good to be home,’ comments the guard and I nod because I am trying hard to be human, just as she is. She waits until her companion strolls over to the soldiers before continuing in a quieter voice, ‘I’ve never seen anything so beautiful. You are a special woman for it to have happened like this.’

I mutter something like maybe or I don’t know. I have long ago ceased to trust people who seem to worship me.

She says, ‘I’m sorry about the van and the handcuffs and all that. About the whole thing. None of it should ever have happened. I hope you’ll be happy now you’re back and . . .’

‘And?’

‘And I hope it rains again, here, I really do and . . .’

‘And?’

‘And, if you still pray, pray for me.’

She tries to grasp my hand. I see she is crying. The tears and the prayers at The Well have been out of balance; there will rightly be more crying than praying from now on. I pull away and for a brief moment she is left staring at her own empty palms, then she turns abruptly and strides back to the van. She gets in, slams the door, leans over and blasts the horn. At the fence, the driver punches something into his phone and half-heartedly salutes the soldiers. Just as he is about to get back into the van, he bends down as if he has dropped something and scoops up a handful of earth to examine like a gardener. He looks up, sees the soldiers watching him and chucks it into the hedge, laughing out loud, then dusts his hands down on his khaki trousers, climbs in and starts the engine. The prison van beeps as he reverses towards the oak tree and he yells out of the window. ‘Don’t worry, lads! We’ll pray for you on your frontline duties!’

The guard sits in the passenger seat, staring straight ahead at the track which will take her away. The driver turns up the music and they are gone and then there is nothing except silence, three soldiers and me. They kick the fence with their heavy boots, one lights a cigarette and suddenly I think of a picture of Russia I saw once, taken during the Second World War: young men silhouetted against a barren landscape, staring at the horizon, waiting for relief. We face a different onslaught. I stand, halfway in and halfway out of the house, my legs shaking with exhaustion.

‘Shall I go in?’ I call and immediately regret my weakness. ‘I mean, are there any other formalities to be completed?’

All three turn, as if mildly surprised that I can speak. A sudden officiousness seems to come over the short one, as it does for all people newly appointed to small amounts of power. He marches over; the other two hang back slightly.

‘There are a number of regulations and procedures we need to go through with you. I therefore suggest that we meet . . . er . . .’ He has a tight voice.

‘Around the kitchen table?’ I suggest.

‘That would be satisfactory, yes – there, in one hour.’

‘You may have to knock and remind me.’

‘We don’t need to knock,’ he replies.

The thinner of the other two tries to make some joke about drinks at six. I don’t quite catch it, but try to smile all the same. Pour encourager les autres.

What do I do now? I try to summon old habits. Like a frightened bride, I force myself over the threshold and then kick off my shoes and go into the kitchen. It is a sparse version of its former self, being robbed of its clutter and wiped down. I run the cold tap just to make sure and then fill the kettle. While it is boiling, I take down my favourite mug and trace the delicate painting of the grayling, trout and perch which swim the porcelain river and wind themselves around the handle, wipe the dust from the rim with the tip of my finger. Instinctively, I go to the fridge, which is working normally. There has been no shortage of wind in the last few years. For us, if our turbine is working, the pump is working and if the pump is working, we will have water from The Well. Water, but no milk. I loathe the powder substitute, it tastes of the city, but the drought has forced a lot of substitution one way or another: no rain, no grass, no grass, no cows, no cows, no milk. We were going to have a cow in Year Three of the dream, but we never got that far.

Most of what Mother Hubbard had in her cupboard is gone, but there is a half-empty box of teabags on the counter, so I use one of those. Sitting at the empty kitchen table, I trace the grain of the wood. Such silence. I shiver; the Rayburn is not lit. That would help, I think, I could warm the place up a bit, but the matches have deserted their home in the top left-hand drawer of the dresser and I don’t know where they have gone. Easily defeated, I wander into the sitting room where the curtains are drawn, my hand hesitates at the window, but even tweaking them opens the way for a javelin of daylight and I leave them closed, for the time being. Moving to the stairs, I put one foot on the bottom step, but make the mistake of looking up. That is too high a mountain to climb now.

The sofa feels damp. Yesterday’s newspaper lies on the table, with the ring of a coffee mug over the face of a topless model. ‘Dress for drought!’ A pale, hollow-cheeked woman in the photo on the opposite page reminds me of Angie, although my daughter would not thank me for the comparison. Flicking through the pages, it is as though I am in a waiting room, regretting not having brought a friend with me to soften the blow.

My name is called, but I am slow to respond. For a few moments, I can’t remember who they are, these men I can see sprawling against the sink and spilling all over the kitchen as I sit obediently, rigid, feeling the wood of the kitchen chair hard against my fatless thighs. Have these men come because of the investigation? No, that was a long time ago and that was the police, not these oversized boy soldiers.

A ringless hand, cuffed in khaki, places a brown file with my name on it in front of me, then opens a laptop and hammers in a password. A voice says the purpose of the meeting is to remind me of my legal status, the reasons for that status, the nature of that status and my rights whilst subject to that status.

Ruth Ardingly is subject to house arrest under the terms of the Drought Emergency Regulations Act, section 3, restriction and detention of persons known to, or suspected of, or deemed likely to act in a way liable to: (i) Disrupt, interfere with or in any way seek to manipulate the supply of essential goods or services, in particular any service relating to the provision of water for drinking, irrigation, manufacturing processes or commerce not covered by exemption clauses outlined in the Drought Emergency Regulations Act, section 4.

I find this funny, being the only subject in Her Majesty’s kingdom who appears to have unlimited access to water and who has no need to siphon it off for my own purposes. The judge and jury in front of me don’t seem to have a sense of humour. What is less amusing is that the period of detention is described as ‘indefinite but subject to judicial review at periodic intervals’ and my questions about what that means in practice are unanswered.

Ruth Ardingly has also been subject to the following Finding of Fact judgments, as used under the Emergency Drought Protection Order Regulations for the Rapid Processing of Justice:

| (i) | that Ruth Ardingly started a series of fires with intent to cause grievous bodily harm or death; |

| (ii) | that Ruth Ardingly was derelict in her duty towards a minor, resulting in death. |

I put my hands over my ears. I will not listen to that. I will not have that said.

The small man drones on.

Under the civil jurisdiction of the Emergency Drought Protection Orders, it is confirmed that the property known as The Well shall remain the principal domiciliary residence for Ruth Ardingly, but that under the terms of the Occupation Order 70/651, Ruth Ardingly agrees for the said property to be temporarily used for the purposes of research and development, including, but not limited to: soil sampling; the planting, management and harvesting of crops; the drilling and sampling of, but not extraction of, bedrock water as defined under the Extraction for Use Act (amended); the collection, sampling and testing (but no distribution of) rainwater run-off.

Despite the small print of my Faustian pact, they don’t own The Well – I won that much. It is still mine; underneath the wire and the helicopters and the men in brown, The Well is still mine. Half mine. It is not clear to me what has happened to Mark’s share.

‘That’s the legal status. Have you got any questions?’ he asks.

Sinking a little, I shrug. He hands over the file to the fat, anonymous man who is apparently going to deal with the ‘nitty-gritty’ of house imprisonment. He reads haltingly, finding it hard to make sense of the interminable regulations. It is as if I am listening to a foreign language, but the broad message is clear. They are my guards. This is my home. Words slide across the paperwork and set off randomly around the room, sliding down the sink, fluttering up the cold chimney, trying to crawl their way out like wasps from a jam jar. The photo we took of Heligan Gardens in the spring and hung to the side of the kitchen window is tilted and this makes it look as if the lake is flowing over the banks and about to trickle down the cream walls and onto the vegetable rack, empty except for the brittle brown flakes of the outer layer of an onion.

Curfew

Bread

Electronic

Rights

Request

Exercise

A sort of Kim’s Game, by which a large number of disparate things are being laid out before me and named in expectation that when they take the tray away, I will remember them.

‘No need to worry about all of this tonight.’ That is the first time the thin one with glasses has spoken since we sat down. He is also the only one who has looked me in the eye.

‘I won’t,’ I reply.

‘Goodnight then,’ he says, for apparently it is bedtime.

‘Goodnight,’ I reply.

I stare after them. ‘I’m sorry, where did you say you were sleeping?’ I ask.

The small one stops at the door. ‘We didn’t,’ he says and he and Mr Anonymous leave.

The thinner, short-sighted one lingers for a couple of seconds. ‘We’re in the barn,’ he says. ‘Not far away.’ He is just a boy. I shall call him Boy.

Little did I know when we ploughed our time and money into renovating the barn that we were building a barracks for my own guards. They’re not the first to move in there and try to control me; they are following in Mark’s footsteps and his footsteps went out of the gate and straight on till morning and I haven’t seen him since. I doubt the guards will forget me so easily.

These guards of mine, what will they do all day? What do they eat? What do I eat? Now their commands have receded, questions appear in their place: thousands of questions about blankets and the internet and food and telephones and children and tomato plants and sheep and baths and books and cutting the grass and, oh my God, everything. I am a toddler again. I want to run after them and hold onto their legs and ask them why, when, how, who. I am in my own house, but I have no idea how I am going to live.

Bedtime. It seems I am going to have to force myself to go upstairs. My fingers remember where the light switches are, but I prefer the dark. I find my way to my bed and, still fully dressed, slide stiffly between the sheets and the duvet which do not smell of prison, but do not smell of home either. Even though it is cold, I leave the shutters open just so I can see the moon over Montford Forest. I will lie here and ask The Well what it thinks of the day just gone and we will reach our conclusions. I will count the sheep I have lost as a way of avoiding sleep, because sleep avoids me. I will compose letters to the ones who are no longer here, because they are no longer here. They no longer hear. I like that pun. I will allow myself the pleasure of the occasional pun. Mark, for instance. I say his name very loudly to confirm his absence. Mark my words. Marking time. And despite the silence, despite the fact that only a wall separates me from the fathomless emptiness of a dead child’s bedroom, I am suddenly knocked sideways with happiness because I am back.

I wonder if it will rain.