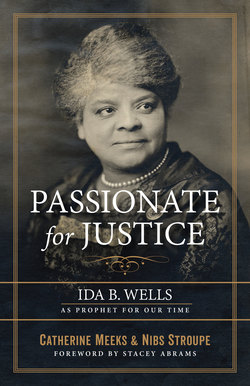

Читать книгу Passionate for Justice - Catherine Meeks - Страница 8

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеCHAPTER 1

“To the Seeker of Truth”

Why Ida B. Wells? Because she did the work no one else would do. She kept showing up where she wasn’t wanted. She worked with people who would work with her. She worked with people she didn’t agree with and with whom she fought constantly. She worked for the betterment of a country that saw her doubly, as a black woman and as a second-class citizen. She lived through some of the darkest times in American history and did not live to see the biggest advancements that her daily work yielded in later decades. Yet she believed in herself, and in her ability to get things done, not just for herself, but for her fellow citizens.

Born in 1862 in Holly Springs, Mississippi, on the land owned by the man who “owned” her father and mother, Jim and Elizabeth Wells, Ida was born just before General Grant’s troops captured Holly Springs in the Civil War. It would be a few more months before Union control of Holly Springs was solidified, but Ida Wells lived the early years of her life in slavery, yet under the oversight of the Union army. On the land where she was born, there now stands not the house of her former owner but rather a museum in her honor and memory.

And remembered she should be! Though born into slavery, she came to consciousness in the time of the Emancipation Proclamation and the defeat of the Confederacy in the Civil War. Thus, her primary definition was not “slave,” not “property of white people”; her primary definition was daughter of God, woman held in slavery by those who professed the idea that all people are created equal. She never allowed that oppression narrative of slavery to enter her heart and consciousness and to become internalized. She never accepted the idea that she and her family were slaves because they were supposed to be slaves. She understood from the earliest stages that she was held as a slave because of the oppressive nature of the masters, and this consciousness made a huge difference in her life and in her imagination.

To gain deeper insight into the dilemma that confronted Wells and continues to serve as the foundation for white supremacy in the twenty-first century, we must travel through several treacherous paths in a short amount of time. This will include race and the naming of the races, as well as the perpetual crushing of people by pushing them to the margins. The modern system of race was not developed as a way to classify the different branches of the human family, but rather as a way of dominating the different branches of the human family. When it developed in the 1600s, as the Enlightenment and science began to grab hold of the European consciousness, it was rooted in the colonizing of the world. The purpose of the system of race was domination, not classification of the great diversity of the human family. If the dignity of the individual is essential in the Enlightenment age, how can we justify the exploitation of other humans from the colonies, if those individual humans have dignity too? The answer was to create a great gulf between those from Europe and those from other lands.

The answer became the system of race, as we currently know it. From the earliest systems of race, this purpose of domination seems evident. One of the greatest scientists of the Western world was Carolus Linnaeus, who developed the basic way of categorizing all living things. He emphasized the diversity of life and yet the commonality of life, and we still use his system today. He was also one of the early developers of the system of race. In 1738, he indicated four racial groups of humanity, and it is revealing to briefly review those categories:

Homo Europaeus—light, lively, inventive; ruled by rites

Homo Americanus—tenacious, contented, free; ruled by custom

Homo Asiaticus—stern, haughty, stingy; ruled by opinion

Homo Afer—cunning, slow, negligent; ruled by caprice.1

Here we see the beginnings of the system of race as we know it today—it is not meant to classify people in different branches of the human family. It is rather meant to indicate who should dominate and who should be dominated. We need a classification system that chronicles and notes the branches and the diversity of the human family, but the system of race is not that system.2 This system works so that people classified as “white,” especially white men, will internalize its approach and believe that we are superior. It also works so that all others will tend to internalize inferiority and believe that white males control almost all the power because they were ordained by God or by biology to do so. There are no significant biological or genetic differences between human beings; the system of race was developed to signify that there are such vast differences between human beings that those classified as “white” should be in power.

Ida Wells lived in the tensions and demonic powers of this system, but she was soaked in a spark of divinity that allowed her to see herself as God’s child. She refused to abide by the attempts to strip her dignity in the post-Reconstruction days that reestablished slavery under the name of “neo-slavery,” or “Jim Crow.” She lived in the tension between equality and slavery in American history. No white person personifies this tension better than Thomas Jefferson. Fifty years after Linnaeus created his formula for the hierarchy of racial classifications, Jefferson gave his thoughts in 1785 in “Notes on Virginia.”3 In his earlier prose, Jefferson had helped to define the American identity: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all {men} are created equal.” This radical idea of equality has been the driving force behind many of the justice movements in our country’s history, including those who have insisted that women are included in this idea of self-evident equality. This powerful idea continues to motivate people of all classes and groups. Writing in 1785, however, Jefferson doesn’t express the certainty of that idea of equality that fired the Declaration of Independence in 1776.

Jefferson waffles on equality because he wants to hold people as slaves while still professing belief in the revolutionary idea of equality. In “Notes on Virginia,” he begins to see a hierarchy in this circle of equality, predating George Orwell’s satirical concept that while all humans are created equal, some humans are more equal than others.4 In his scientific analysis, Jefferson puts the “Homo sapiens Europaeus” on top of the racial ladder, with “the Indian” next and “blacks” on the bottom. While hoping to be objective and scientific, Jefferson admits that much more study is needed. Yet he must add this conclusion: “I advance it, therefore, as a suspicion only, that the blacks, whether originally a distinct race, or made distinct by time and circumstances, are inferior to the whites in the endowments both of body and mind.”5

Although Jefferson later expresses misgivings about his dismissal of the equality of black people, his ruminations reflect the difficulty of all those who are classified as white in our society, whether in 1785 or 1985 or 2019. While committed to the idea of equality, there are also distinct economic privileges to the inequality inherent in the system of race that places white folks on top of the ladder. For all of his misgivings about slavery, Jefferson benefitted immensely from it. At his death, his will freed only five of his slaves, all from the family conceived through his relationship with his slave Sally Hemmings.

While many who are classified as “white” would disavow the power of race and racism in our lives, the benefits cannot be denied. Jefferson shared this struggle, even as he quoted “scientific” evidence that seemed to verify that Africans were less equal than Europeans. If Africans were less than Europeans, then the “self-evident” clause of equality might not apply to them, and maybe, just maybe, holding them in bondage might be justified. In one form or another, throughout our history, “white” folk have gone through the same process as Jefferson did in order to justify the many privileges that come to those classified as “white” under the system of race. It was certainly true in the days of Ida Wells.

In 1875 in its last significant law for civil rights until 1957, the US Congress passed an act that forbade segregation on public accommodations. In 1883, the United States Supreme Court ruled the Civil Rights Act of 1875 unconstitutional, and the floodgates of segregation and reenslavement were open fully. In the spring of 1884, Ida Wells followed her usual pattern of purchasing a seat in the ladies’ car on the train on a trip out of Memphis. After the train had pulled out, the conductor came to collect the tickets and then informed her that she would have to move to the car reserved for black people. Seventy-one years before Rosa Parks, she refused to give up her seat, and when he grabbed her and tried to pull her up from her seat, she bit his hand and braced herself not to move—no nonviolent resistance for her. He went to get male reinforcements, and it took three men to throw her off the train.

Undeterred, she took the railroad to court under Tennessee law, and the white judge who heard the case was a former Union soldier. He ruled in her favor and awarded her $500 in damages. She was thrilled with the victory, but it was short-lived. The railroad appealed to the Tennessee Supreme Court, and in 1887, they overturned the verdict. Ida Wells was crestfallen and wrote in her diary on April 11: “I had hoped for such great things from my suit for my people generally. I have firmly believed all along that the law was on our side and would, when we appealed to it, give us justice. I feel shorn of that belief and utterly discouraged, and just now if it were possible would gather my race in my arms and fly far away with them.”6

Wells was beginning to learn that the power of racism was deep and wide in those classified as “white,” and she would later lift up a phrase that Ronald Reagan would use as one of his hallmark phrases: “Eternal vigilance is the price of liberty.” Wells meant it in the sense that we know it today: racism is deeply embedded and intertwined in our American consciousness, and we must always be working to mitigate its loathsome power.

Though some marked the Obama presidency as the death knell of the power of racism, many in the South did not. We were astonished at this turn of events that led to his election, but as native Southerners, raised in the power of white supremacy, we knew that the hold of racism remained mighty in our hearts and in our structures and institutions. The racism that undergirded slavery and neo-slavery is both resistant and resilient, and much work needs to be done to dislodge its power from our individual and collective hearts. We wished that the election of Barack Obama as president could have changed that, but we also knew that it could not and did not.

In regards to race in America, there are at least three passages that we have all traveled. The first was the European landings and settlement, when cheap labor was needed to work the land and grow the economy. Indentured servants and slaves were brought to do this work. During this time, the idea of race and slavery were married, and the idea developed that people of African descent were meant, by God and by biological destiny, to be slaves forever. This marriage was debated fiercely at the adoption of the Constitution: does the idea of “all {men} created equal” in the Declaration of Independence apply to those people held as slaves? The slaveholders won the battle at the constitutional convention, and indeed people held as slaves (and native Americans) were deemed to be 60 percent human beings.7

The second passage occurred at the Civil War, Reconstruction, and its aftermath. Through the dedication of many abolitionists and soldiers and the deaths of almost 700,000 in the Civil War, some progress was made to seek to establish the humanity and citizenship of those designated as “black.” In a speech given in 1965, James Baldwin describes the situation, “So where we are now is that a whole country of people believe I’m a ‘nigger,’ and I don’t, and the battle’s on! Because if I am not what I’ve been told I am, then it means that you’re not what you thought you were either. And that is the crisis.”8 The idea of “niggers,” an idea at the heart of white supremacy, dwells deeply in the American psyche, however, and it did not take long for the slaveholders to use violence, racism, and legislation to reestablish what Doug Blackmon calls “neo-slavery.”9 By the decade of the 1890s, white supremacy was in full bloom in the South and in other places. The 1896 Supreme Court ruling in Plessy v. Ferguson reinforced and codified this idea that Baldwin illuminated, that we as a country believed that we needed our “n-words.” Neo-slavery was firmly reestablished, and it would last until 1965.

Fortunately for us all, there were people classified as “black” (and a few classified as “white”) who were determined to fight for the idea of equality and the recognition of the humanity of black people. All through those years, there were strong voices such as Ida Wells, who fought for a different point of view, a view more closely aligned with the idea that all people are created equal. This led to the third passage, which caught fire in the 1950s, with the Supreme Court decision of Brown v. Board of Education in 1954, the Montgomery bus boycott of 1955–56, and the lynching of Emmett Till in 1955. These and many other actions would lead to the passage of the Civil Rights Act in 1964 and the Voting Rights Act in 1965, which offered the promise of ending neo-slavery. As before in the other two passages, white supremacy roared again. We are not sure how the transition for this third passage on race and white supremacy will end in our country.

Nibs remembers his sense of hope on a cold, dark January morning as he arrived at the Silver Springs Metro Station to get on the train about 6 a.m. In spite of the cold and early hour, there was a festive atmosphere, as more and more people boarded the train as it made stops on the way to Union Station in DC. We were celebrating a moment that we had thought we would never see—the inauguration of the first black man ever elected president of the United States. We passed through the security checkpoints near the Capitol, and then found our seats. There were over one million people in the National Mall that day, and as far as I could tell, we were all celebrating this remarkable achievement and this remarkable person.

And now, as we write this, we see the answer of white people to the Obama presidency: we are in the third year of the presidency of Donald Trump. He was elected by white people, with the majority of white people of both genders voting for him. We should not be surprised at this turn of events. With a few notable exceptions, the idea that white men are superior has been a staple of the American scene since the European beginnings. The idea that “all men are created equal” was originally intended to mean white men, but fortunately others have heard that it applies to them! Many of us were surprised that Donald Trump was elected president of the United States, yet history reminds us that whenever there is some advance toward racial or gender justice, there is a backlash and a regathering of white male power.

The election of 2020 will tell us much about our future, but for now we must seek the wisdom and justice that we can. This is a crucial time in our history, and another time of great danger, as reactionary forces seek to turn back the small tides of progress that has been made. Though it feels brand new and unique, our time bears many similarities to the years after Reconstruction, when hard-won rights for African Americans were stripped away by the resurgence of the power of white supremacy. Thus, it is fitting to turn to our elders and witnesses, as we are doing in this book.

Ida Wells was born in slavery, grew and matured during Reconstruction, and fought fiercely for the freedom that she found in the Reconstruction time. She did this while it was being stripped away in a tidal wave of racism and white supremacy. Her life and witness offer hope and possibility for us.

Though American history is rather pessimistic on this level, we choose to be inspired by Ida Wells whose life was dedicated to the idea of equity and justice for all. Her life and witness remind us of the fierceness and dedication needed to be a voice for justice, touching so many points of “intersectionality”: categories such as race, gender, class that overlap one another and are in conversation—and often in tension—with one another. And we are focusing on her because her witness has been greatly undervalued in American history. In these challenging times, we must be guided by her life and witness—though she did not win as many victories as one wishes she had, she was never defeated.

1. Jacques Barzun, Race: A Study in Superstition (New York: Harper and Row, 1965), 35.

2. For fuller discussion of this development, see Nell Painter, The History of White People (New York: W. W. Norton and Company, 2010).

3. Thomas Jefferson, “Notes on the State of Virginia,” in Documents of American Prejudice, ed. S. T. Joshi (New York: Basic Books, 1999), 11.

4. George Orwell, Animal Farm (New York: Harcourt, Brace and World, 1954).

5. Jefferson, “Notes on the State of Virginia,” 11.

6. Miriam Decosta-Willis, ed., The Memphis Diary of Ida B. Wells (Boston: Beacon Press, 1995), 140–41.

7. Laurence Goldstone, Dark Bargain (New York: Walker and Company, 2005), 104–7.

8. James Baldwin, Price of the Ticket (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1985), 325–32.

9. Douglas A. Blackmon, Slavery by Another Name (New York: Doubleday, 2010), 402.