Читать книгу Attack of the 50 Ft. Women: How Gender Equality Can Save The World! - Catherine Mayer - Страница 9

ОглавлениеIntroduction: The Shoulders of Giants

A COLOSSAL ZOMBIE Scarlett Johansson commandeered London’s red buses a few years ago. She sprawled across the upper deck of a fleet of vehicles, face slack with simulated desire, mouth gaping wide enough to swallow a small terrier, breasts threatening to smother passengers seated in the lower tier.

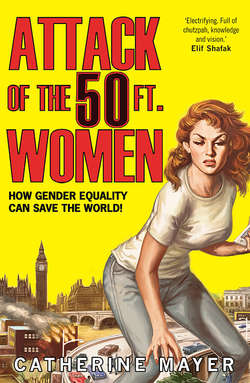

Dolce & Gabbana’s advertising campaign intended to evoke Marilyn Monroe’s heyday, and it succeeded. The apparition recalled Nancy, the title character of a 1958 film, Attack of the 50 Ft. Woman. Nancy’s encounter with a space alien transforms her into a giant (‘Incredibly Huge, with Incredible Desires for Love and Vengeance’). The patriarchal authorities – doctors, police, spouse – chain her, but she breaks free and, naked but for an arrangement of bed sheets, embarks on a murderous rampage. Behold the dreadful power of woman unleashed (‘The Most Grotesque Monstrosity of All’)!

Zombie Johansson captured the inadvertent humour of the B-movie, but she was properly scary too. In her human incarnation she is the only woman to break through Hollywood’s diamond ceiling to claim a place among the ten top-grossing actors of all time. She chooses intelligent roles and has more than once pushed back against the chauvinism of Hollywood and its media ecosystems. Her dead-eyed alter ego belonged to the monstrous regiment of billboard women in perpetual march across the world. Nancy gained agency as she grew. Today’s 50-footers, hypersexualised and supine, promote a retrograde ideology alongside brands and products.

We’re so marinated in this imagery that we seldom stand back to parse its meaning and impact. It is all-pervasive, not just on hoardings and print and broadcast but metastasised into myriad digital forms. The underlying messaging is little different to the drumbeat that helped return women to pliant domesticity after World War II. From earliest childhood, girls are taught to value themselves for their abilities: desirability, marriageability, tractability.

There are, of course, other role models, women of stature and astonishing achievement, but still they break through against the odds. Globally women own less and earn less than men, often in the worst and worst regulated jobs, undertake the lionesses’ share of caregiving and unpaid domestic labour, and are subject to discrimination, harassment and sexual violence.

Every woman navigates a world fashioned by and for men. Some pharmaceuticals fail us because they are tested on male animals to avoid having to account for hormonal cycles. We shiver at our workplaces because thermostats are set to temperatures that suit male metabolisms.

We’re left in the cold in other ways too. On February 6, 1918, the Representation of the People Act gained royal assent, for the first time giving the vote to UK women, if only to those 40 per cent of UK women aged over 30 who met additional criteria such as property ownership. The Parliament (Qualification of Women) Act, a piece of legislation that came into force in November of the same year, meant these 8.4 million voters were not only able to exercise their new right at the December general elections, but in 17 constituencies could vote for Westminster’s first female candidates – returning to office the first female MP, Constance Markievicz. Yet the centenary of these momentous events opened not just with a popping of corks for the progress they enabled, but with a flatulence of punctured hopes. In 2018, the total number of female MPs ever elected surpasses the number of male MPs in the current parliament by only two, and that parliament presides over a country in which to be born female is still a lifelong disadvantage. The Organisation for European Economic Co-operation (OECD) logs the gap between women’s earnings and men’s at 17.48 per cent in the UK, and this pattern is echoed across the world, with a gap of 17.91 per cent in the US and 18 per cent in Australia. Women have long been blamed for this gap. We don’t ask for raises often enough or we don’t ask right. Studies identify the real culprits: job segregation and discrimination.

Jobs traditionally performed by men attract higher wages than those held by women. The paradigm of the husband as the head of the household remains firmly lodged in the public imagination. One reason some employers pay men better may be that they think the men have greater need of the money. In the US, men in nursing are vastly outnumbered by their female colleagues, by nine to one, yet earn $5,100 more on average per year than female nurses. These disparities are echoed across the world.

Every woman lives with the constant tinnitus hum of low-level sexism. Most of us have been leered at or leched over and told we should be flattered by the attention. Almost a fifth of US women will be raped in their lifetimes, with close to half reporting other forms of sexual violence. One in three women worldwide will be subjected to violent sexual attack. The response to this epidemic is muted and muddled.

US prosecutors ask a judge to send a college athlete to prison for six years for sexually assaulting an unconscious woman; the judge decides on six months, concerned a longer period of incarceration will have a ‘severe impact’ on the perpetrator, who is then freed halfway through his sentence. In India, a woman is gang-raped to death; one of her rapists says: ‘A decent girl won’t roam around at nine o’clock at night. A girl is far more responsible for rape than a boy.’ In Russia, where domestic abuse is thought to kill one woman every 40 minutes, legislators find a way to reduce criminal cases of domestic violence – by decriminalising ‘moderate’ violence and reserving criminal penalties for cases where beatings result in broken bones. The majority of the 276 schoolgirls kidnapped by terrorists in northern Nigeria are still missing; those who escape bearing tales of mass rape and slavery find themselves social outcasts. Egyptian lawmakers finally approve a draft bill that would dole out five-to seven-year jail terms for people carrying out female genital mutilation (FGM), an operation to remove part or all of the clitoris. The procedure – often called circumcision by those trying to minimise its brutality – has been inflicted on more than 90 per cent of the country’s women and girls. ‘We are a population whose men suffer from sexual weakness, which is evident because Egypt is among the biggest consumers of sexual stimulants,’ an MP protests. ‘If we stopped circumcising we will need strong men, and we don’t have those.’ Up to 1,000 women are sexually assaulted on the streets of the German cathedral city of Cologne on New Year’s Eve 2015; the attacks trigger condemnation not of women’s oppression but of migration, reinforcing the false narrative that sexual violence is imported, rather than native to white European society. In October 2017, the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences votes to expel producer Harvey Weinstein amid allegations by dozens of women of harassment, assault and rape. As details emerge, more women come forward, with stories not only about Weinstein but the entire film industry and then about other industries and, of course, about politics. A UK government minister, Mark Garnier, admits calling his female aide ‘Sugar Tits’ and does not deny sending her to buy sex toys, but blusters that this ‘absolutely does not constitute harassment’. Michael Fallon, Secretary of State for Defence, resigns after admitting he touched a journalist’s knee. Another journalist says he lunged at her. More Conservatives are accused of pawing and worse, but so too are MPs from other parties. Bex Bailey, a Labour activist, reveals that when she told a party official she’d been raped by a senior colleague, the official advised her that to report the assault would ‘damage’ her. This ‘is a problem in every party at every level,’ says Bailey.

Across the world, similar stories come to light. During a debate in the EU Parliament, several female members hold up handwritten signs that say ‘#MeToo’. The backlash starts quickly. This is, powerful men complain, a ‘witch-hunt’, yet the flood of stories shared on Twitter using the #MeToo hashtag are only revealing what women already knew, that sexual violence, threatened or actual, is part of our everyday experience. When the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences proclaims an end to ‘the era of wilful ignorance and shameful complicity in sexually predatory behaviour and workplace harassment’, we shake our heads in disbelief. When the President of the United States muses that ‘women are very special. I think it’s a very special time. A lot of things are coming out and I think that’s very, very good for women, and I’m happy a lot of these things are coming out. I’m very happy it’s being exposed’, our jaws hit our chests. Because this is patently untrue.

The previous November, US voters have chosen Donald Trump despite hearing a recording of him boasting of assaulting women. ‘Grab them by the pussy. You can do anything,’ he said. The recording prompted ten women to come forward to accuse him of assault, often in workplace settings. He insisted that they were lying. After all, two of them were too ugly to grope.

Many other aspects of his candidacy should also have repelled any voter who values equality. The candidate appeared to believe only in himself, but pandered to Christian social conservatives by promising to roll back women’s reproductive rights. He pledged to ban Muslims from the country and force Mexico to build a wall to keep its own citizens from crossing the border into the US. He refused to condemn his supporters for racist violence. He publicly invited the Russian secret service to hack US government emails to damage his opponent and announced he would unpick years of international negotiations to limit climate change – which he called a ‘hoax’.

He was, without a shred of doubt, the worst would-be President we had seen in our lifetimes or read about in history books – dangerous, incoherent and vain.

And yet to a significant slice of America, he appeared a better bet than his female challenger.

A majority of men voted for him, by 53 per cent to 41 per cent.

A majority of white people voted for him, by 58 per cent to 37 per cent.

Eighty-one per cent of white evangelicals and born-again Christians voted for him.

Women voted against him, by 54 per cent to 42 per cent. Yet a majority of white women supported him: 53 per cent.

A dual US and UK national, I cast a ballot in my home state of Wisconsin. I am not one of the white women who helped Donald Trump into the White House, but like all white American women, I am implicated. Through researching this book, I also understand the mechanisms that encourage turkeys to vote for Christmas.

This book aims to set out those insights and to make something else abundantly clear. The skewed status quo serves almost nobody – certainly not most men.

The world is full of decent men who strive to be allies to women. It’s a safe bet that most men who are engaged enough in these issues to read these pages fall into this category, though you may not always be sure how best to support us. Many of you want change, for women and girls and for yourselves, but you don’t always understand that ‘women’s issues’ are your issues. You observe your own sex suffering within patriarchal cultures and structures but don’t always join the dots. Because of these structures, boys struggle at school; suicide rates are highest among young males, who are also more likely to murder and more likely to be murdered; and men drink more heavily and more frequently end up in prison. Fathers yearn to be with their children, but the enduring pay gap means they cannot afford to stay home, while social norms sometimes deter them from pushing for change. Businesses, institutions and economies underperform.

The twenty-first century wasn’t supposed to be like this.

Late boomers like me grew up believing history was going our way. We assumed progress to be linear, counting ourselves lucky to be born to an era that had all but vanquished the great scourges of humanity. Racism and homophobia proved susceptible to education and so would wither. Wars were still prosecuted, but at a distance. Hunger, too, seemed confined to far-away lands, and technology must surely deliver fixes, just as it would soon banish cancer, ageing, death and clothes moths. As for women’s rights, the heavy lifting had been done by the women, and their male allies, who came before us. A liberal consensus held sway and growing up in comfort, largely surrounded by the white middle classes, I had no idea of the limits or vulnerabilities of our progress.

After a peripatetic early childhood, I attended a girls’ school in Northern England that proudly counted among its alumnae all three daughters of the magnificent, if flawed, Emmeline Pankhurst. We learned that in 1918, as Europe made its fragile peace, Suffragettes and the more peaceable Suffragists, led by Millicent Fawcett, hailed the beginning of the end of the gender wars as women for the first time voted and ran for parliament. A decade later, all adult females got the vote. New Zealand had led the way in 1893. The US followed suit in 1920. When I was seven and still living in the US, the doughty women of Ford Dagenham fought and won the battle for equal pay. Women’s libbers and the Pill were finishing the job. As teenagers my contemporaries and I saw shimmering on the near horizon a fully gender-equal society in which every inhabitant could stand as tall as the next person.

I named this place ‘Equalia’, and like a querulous child on a family outing, I’ve spent much of my life asking ‘When will we get there?’ There’s always someone prepared to claim we’ve already arrived. Such people rarely describe themselves as feminists because they misunderstand the term as a doctrine of suppression.

The media maintains lists of pundits who can be relied on to declare that Western women already have enough equality. After all, most Western countries have legislated for equal pay, even if the legislation hasn’t achieved the desired result. The laws and their application cannot be faulty; women must be choosing their lower status. Sex discrimination and sexual harassment are outlawed, so women must deserve this treatment. We never had it so good. We should stop whingeing and worry about Saudi Arabia. (It is axiomatic among these useful idiots that you cannot advocate for the rights of women in your own country and in Saudi Arabia.) Feminism can go home and put its feet up.

Broadcasters are particularly fond of pitting women against women. The anti-feminist female is as persistent a breed as the clothes moth. Typically white and middle class, she either doesn’t believe in gender equality or else she doesn’t believe in gender inequality – because she’s too cocooned and myopic to see it. She routinely seeks to strengthen her case by co-opting a tenet of feminism: that the personal is political. She feels no kinship with younger and less privileged women still fighting the old battles while simultaneously picking their way through new and dangerous territories. She declares that she has never experienced sexism or discriminatory behaviour she couldn’t handle. She is thriving.

Let us celebrate the advances that enable her complacency even as we sometimes doubt her sincerity. Her protests are too vigorous, her unease in her own skin too obvious. Her mind has hardened with habit into narrow pathways and she cannot conceive how her own discomfort might relate to a wider pattern. The men around her give succour to her views.

‘The war has been won,’ one such tells me. ‘It’s just a mopping up operation now. You can’t even kick your dog now much less your wife.’ Yet, make no mistake, we haven’t reached Equalia. The Most Grotesque Monstrosity of All? We’re still a long, long way from Equalia.

We live, wherever we live, under a patriarchy, a system that excludes women. Not a single country anywhere on the planet has attained parity. The Nordic quartet of Iceland, Norway, Finland and Sweden tops the rankings of the best places to be female. Even in these countries, though, girls start life as second-class citizens and will be demoted further down the unnatural order with every year beyond their socially determined prime, or if poor or non-white or disabled or daring to combine any of these factors.

There is increasing awareness that gender is not binary but a spectrum, yet this awareness has neither diminished gender conflict nor created acceptance for people transitioning along the spectrum or sitting at junctions that challenge bureaucratic or social labels. Groups that are themselves disadvantaged unconsciously incorporate patriarchal pecking orders. Gay men have a habit of crowding out the other letters in the LGBTQ movement. Civil rights activists have form too. In 1964, Stokely Carmichael, a leader of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, batted away a question about women volunteers. ‘The position for women in SNCC is prone,’ he said. It was, he later explained, a joke, but one that closely matched the experience of women in progressive movements. Black Lives Matter, founded by three women: Patrice Cullors, Alicia Garza and Opal Tometi, to illuminate the high – and under-reported – toll of racially motivated killings of black Americans by whites, focuses increasingly on the killings of black males by law enforcement officers. This is hugely important but killings of black women get less attention, prompting a separate movement to take up the cause, #SayHerName.

The elites that might be expected to forge solutions are themselves part of the problem. There is a startling lack of any kind of diversity in politics, and the gender imbalance is stark. Westminster isn’t the only legislature where men dominate, and all political cultures struggle with, and usually succumb to, misogyny. America blew its chance to finally elect a woman to the White House amid barbs about blow jobs. ‘Hillary sucks, but not like Monica’ read T-shirts and badges flaunted by Trump supporters. Bill Clinton, at 49 and President of the United States, did have sexual relations with 22-year old White House intern Monica Lewinsky. Hillary Clinton, like Lewinsky, continues to be vilified for his actions. Sexism and misogyny were by no means the only drivers of her defeat, but they certainly played a part. Still, women had cause to celebrate the elections according to the US media outlets that trumpeted ‘the highest number of women of colour on record’ to win seats in the Senate. That record-breaking grand total equals just four: Catherine Cortez Masto, Tammy Duckworth, Kamala Harris and Mazie Hirono. The number of female representatives in both houses remained static at 104, a mere 19.4 per cent.

Business is just as bad. Among CEOs of the biggest companies in the UK and the US there are more men called John than women of any name. Financial institutions in both countries are overwhelmingly white, male and middle class. Other key institutions – the judiciary, the police, the media – share the same weaknesses.

Here’s something else they share: most of them claim, institutionally and individually, to support gender equality. The liberal consensus is still alive but it is under concerted attack from different expressions of political and religious extremism. The forces ranged against it aim not only to destroy it, but to dismantle its legacy of rights and protections. Progress is not, after all, linear, and it is far too easily reversed.

We would not have so much to lose if not for the achievements of feminism. Its Western incarnation loosely divides into four eras, or waves. The first, in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, coalesced around the battle for votes for women. The second kindled in the 1960s, and asserted reproductive rights as a tool of liberation that would enable women to define their own being and sexuality and participate alongside men outside the home. It often rejected the possibility of equality within existing systems and structures. A third iteration in the 1990s grappled with the movement’s own failings to address systemic inequalities in its own ranks, while another strand attempted to seize ownership of male ideals of womanhood and recast them as female empowerment. The 1993 remake of Attack of the 50 Ft. Woman, starring Daryl Hannah, becomes a parable of emotional as well as physical growth, and gets a happy ending.

We’re now well into a fourth era, more of a torrent than a wave thanks to the proliferation of digital media, and too fast-flowing to analyse easily. It doesn’t help clarity that so many people lay claim to be part of that flow. Business leaders insist that finding and retaining female talent is essential to success. Economists hail increasing gender balance in the labour force as the key to growth. One recent report estimates a boost to global GDP of £8.3 trillion by 2025 simply by making faster progress towards narrowing the gender gap. Two large-scale pieces of research by Credit Suisse suggest that companies with significant numbers of women in decision-making roles are more profitable. Multiple studies also show that giving women a greater say – and a greater stake – in the planet is essential to building a healthier planet. Trump rushed to withdraw the US from the Paris accord, continuing to voice doubts about the reality of climate change. Among the rural poor, women don’t have the luxury of such doubts. They are at its sharp end, because females are most often tasked with sourcing water, food and energy for their families and communities. In 25 sub-Saharan countries, 71 per cent of the water collectors are women and girls who every day spend an estimated 16 million hours fetching water, compared to six million hours spent by men. The worse the drought, the longer the journeys and the greater the vulnerability of those women and girls. In India, 75 per cent of rural women work in agriculture but own only nine per cent of arable land. Bina Agarwal, Professor of Development Economics and Environment at the University of Manchester, posits that increased female participation in business decision-making improves environmental outcomes.

Agarwal rejects the romantic idea that this is because women are in some way closer to nature than men, but much of the current orthodoxy identifies women as a corrective to testosterone-driven cultures. The Credit Suisse studies find companies steered by women take fewer risks. ‘Where women account for the majority in the top management, the businesses show superior sales growth, high cash-flow returns on investments and lower leverage,’ says the 2016 report.

Politicians of many stripes laud women and profess to fight for us. Congresswoman Ann Wagner went so far during the US election campaign as to call on her own party’s nominee to stand aside because of his misogyny. ‘As a strong and vocal advocate for victims of sex trafficking and assault, I must be true to those survivors and myself and condemn the predatory and reprehensible comments of Donald Trump,’ Wagner said in an October 2016 statement. Less than a week before polling day, she urged voters to back Trump, and has subsequently become an enthusiastic cheerleader for his dismantling of the Affordable Care Act, better known as Obamacare. Thirteen male Senators drafted Trump’s first attempt at a replacement bill, which restricted funding for Planned Parenthood and access to abortion insurance, and would have allowed companies providing healthcare insurance to charge women more for ‘pre-existing conditions’. That might sound reasonable until you consider the conditions – pregnancy, Caesarian sections, post-natal depression, domestic violence, sexual assault and rape.

Wagner has been unlucky in one respect. Political commitment to gender equality is often little more than skin deep, but a great many politicians get away without their commitment being so publicly tested and found wanting. This is not to paint all politicians as hypocrites. Many of them believe in women. It’s just that when push comes to shove, they believe in other things more – and they also make the mistake I once did, of assuming that gender equality is already well on its way, without any extra help from them.

If there is a sliver of a silver lining to Trump’s victory, it is that it dented this myth. It did not destroy it. Clinton’s defeat seemed to contrast a regressive US with feminising cultures elsewhere. Patricia Scotland had recently taken office as the Commonwealth’s first female Secretary-General. Estonia had its first female president. Rome and Tokyo for the first time had elected female mayors. After a campaign dominated by male voices tore up the UK’s membership of the European Union and Prime Minister David Cameron stepped down, Britons wondered if women might save the day. Some looked with envy at Germany and its unflappable Chancellor Angela Merkel. More than a few English voters discovered a new reason to beg Scotland not to secede; they wanted the country’s clever First Minister Nicola Sturgeon to be Prime Minister of England too. Britain’s two biggest parties, the governing Conservatives and Labour opposition, turned hopeful eyes to senior women in their ranks. There was, after all, precedent. In 1979, the British economy seemed locked into a downward spiral of a weakening currency and blooming inflation, amid industrial unrest that saw even gravediggers down tools. Then a general election returned Margaret Thatcher to Downing Street, the first female Prime Minister not only of the UK but of any major industrial democracy. Within a few years, her economic policies had laid waste whole communities and sectors but galvanised others and, more than that, revived a sense of potential that had long been missing.

She set a template for the female leader who sweeps in to sort out the mess created by men. Cometh the hour, cometh the woman. The press dubbed Merkel Germany’s Margaret Thatcher. Inevitably Sturgeon became Scotland’s Margaret Thatcher and Theresa May transmogrified into Margaret Thatcher in kitten heels or, when that comparison wore thin, Britain’s Merkel. ‘Women are such rare creatures that they can only be understood through the prism of one another, like unicorns or sporting triumphs by the England football team,’ observed the journalist Hadley Freeman.

This barb held true after May entered Downing Street as Britain’s second female Prime Minister, called a June 2017 snap election aiming to increase her mandate to negotiate Brexit and instead lost the Conservatives their parliamentary majority. This left her government dependent on the backing of the Northern Irish Democratic Unionist Party (DUP), a party led by another woman of tarnished reputation, Arlene Foster. Northern Ireland’s delicate power-sharing agreement had foundered over Foster’s role in a scandal involving an overgenerous incentive scheme to boost renewable energy that handed taxpayers a hefty bill. May and Foster display many weaknesses as politicians. Their critics attack them as female politicians. The journalist and broadcaster Janet Street-Porter typified this approach, writing a piece entitled ‘Theresa May’s incompetence has set women in politics back decades.’

Women aren’t immune to making sweeping assumptions about women, about female difference – whether that difference is female failure or, just as often, female superiority. ‘If Lehman Brothers had been Lehman Sisters, today’s economic crisis clearly would look quite different,’ IMF chief Christine Lagarde told an interviewer in 2008.

The idea of women as the antidote to male leadership is a familiar discourse in public life. Whenever economies falter or politics stutters, the refrain starts again. Men plunder the environment; women manage it. Men start wars; women make peace. We need more women in high and influential positions. We need more women to tower. Bring on the new breed of 50-foot women!

With so many people apparently inclined to this argument, not just rebels and advocates of social justice, but great swathes of the political classes, pillars of the establishment, corporate bigwigs and analysts focusing so hard on the bottom line that they walk into lampposts, surely we must be able to make substantial progress towards gender equality? With the dangers of failure laid bare in countries that are shredding hard-won rights, surely we have no choice but to redouble our efforts? Where are the traps and barricades obstructing the road to Equalia? Does anyone even know the way? And will it take 50-foot women to get us there?

In 2015, I kicked off a process that would provide fascinating and unexpected answers to those questions.

I accidentally started a political party.

Westminster’s first-past-the-post voting system reliably delivered single-party victories until a Conservative–Liberal Democrat government emerged from the 2010 elections. Five years later, as fresh elections hove into view, the coalition partners sought to win voters’ favour by vilifying not only the Labour opposition but each other.

For that reason alone, the political debate I attended at London’s Southbank Centre on 2 March 2015 felt excitingly unorthodox. As part of the Women of the World (WOW) Festival, the Conservatives’ Margot James, the Lib Dems’ Jo Swinson and Labour’s Stella Creasy described overlapping experiences and ambitions. They debated companionably, listening intently, nodding appreciatively and applauding each other’s points.

This should have been thrilling. Instead it was dispiriting. In 66 days we faced a choice not between these vibrant women but their parties.

Lehman Brothers’ collapse in 2008 had ushered in an age of deficit-cutting measures that often hit the poorest hardest, and that meant a disproportionate impact on women. In the UK, as in most other countries, the male-dominated mainstream that steered towards the crisis also took the wheel to direct the recovery.

There were significant dividing lines, of course. Tories, Lib Dems and Labour disagreed over the degree, speed and targets of proposed cuts, but not one of them made serious efforts to apply a gender lens to the discussion. They needed only to look over to tiny Iceland to see the difference that could make. Prime Minister Jóhanna Sigurðardóttir did attract international attention – she wasn’t just Iceland’s first female Prime Minister, she was the world’s first openly lesbian premier. Less noted, and at least as noteworthy, her coalition took a consciously gender-aware approach to the economic crisis. The country’s three largest banks had failed, its currency collapsed, the stock market plummeted and interest on loans soared. As businesses bankrupted, jobs vanished. Cuts in state spending were inevitable, but in planning them, Jóhanna’s coalition tried to diminish the pain by spreading it thinner. Where other nations slashed state sector jobs and prioritised capital investment, effectively supporting male employment at the expense of sectors employing and serving women, Iceland took a different tack. It asked a simple question: why build a hospital, but cut nursing staff?

‘The typical reaction of a state to a crisis is to cut services because they’re seen as expenses,’ says Halla Gunnarsdóttir, who served as a special adviser in the Icelandic coalition. ‘The state puts money into construction because it’s seen as investment. So basically it cuts jobs for women, and also takes away services and replaces them with women’s unpaid labour: care for the elderly, care for the disabled, caring for children and those who are ill. Then it creates jobs for men so that they can continue working.’ This is often done through public–private partnerships in which the state takes the risk but the private sector benefits. Women’s unemployment goes up as the state focuses on preserving jobs for men.

Such perspectives – and women themselves – were conspicuous by their absence in Britain’s 2015 election and the broader landscape looked bleak. Of 650 electoral constituencies, 356 had never elected female MPs. Labour did better on getting women into Parliament, but the Tories remained the only major party to have chosen a female leader, and that had been 40 years earlier.

Labour women did try to elbow their way into the front line of the campaign. Harriet Harman, the party’s deputy leader, long saddled with the nickname ‘Harperson’ by sections of the press hostile to her feminist politics, commissioned research that revealed that 9.1 million women had chosen not to exercise their votes at the previous election. ‘Politics is every bit as important and relevant to the lives of women as it is to men. Labour has set itself the challenge to make this case to the missing millions of women voters,’ she said.

In truth, Labour had done no such thing. Harman couldn’t get her male colleagues to treat gender as a core issue, and ended up scrambling together a separate campaign. Her party had a proud heritage on women’s equality: it appointed the first ever female cabinet minister (Margaret Bondfield in 1929), pioneered equal pay legislation, made strides on early years provision for children, and in introducing all-women shortlists in 1997 engineered the biggest single increase in female representation in the Commons. Of the intake of 418 Labour MPs elected in Tony Blair’s first landslide victory, 101 were women. The total number of female MPs in the previous parliament across all parties had been just 60.

Yet these achievements sit alongside more problematic strains, a culture descended from a struggle for the rights of the working man that often viewed female workers not as part of that struggle but as competition, and an ideological underpinning that in seeing gender inequality as fixable only by fixing all power imbalances too often sends women to the back of the queue to wait their turn. In every vote for the Labour leadership involving women, female candidates have come last. In 2016 MP Angela Eagle withdrew her bid to replace Jeremy Corbyn after a male MP put himself forward, in a brain-twisting piece of logic, as an alternative unity candidate. ‘If Labour had an all-women leadership race, a man would still win,’ tweeted the journalist Stephen Daisley.

Harman had climbed higher in Labour than any other woman, elected the party’s Deputy Leader when Gordon Brown succeeded Tony Blair in Downing Street. Her predecessor as Deputy Leader, John Prescott, had also served as Deputy Prime Minister. She never got that status and further slights followed. ‘Imagine the consternation in my office when we discovered that my involvement in the London G20 summit was inclusion at the No. 10 dinner for the G20 leaders’ wives,’ Harman said later. Heading into the 2015 election, now deputy to Ed Miliband, Harman found herself sidelined by male advisers, consultants and politicians. Her riposte trundled into view in February of that year, apparently blushing with shame that such a stunt should be necessary.

‘That pink bus! Oh my god, the pink bus!’ Sitting in a café in the Southbank Centre, I listened to a table of women holding their own debate ahead of WOW’s. They, like me, found the political choices on offer to voters about as exciting as a limp egg-and-cress sandwich. They, too, cringed to see Harman’s pink bus touring constituencies with its cargo of female MPs. For all its noble intent – and its effectiveness; the negative publicity generated what spin doctors call ‘cut through’, drawing voters who might otherwise not have engaged – it was tough to get past that pinkness.

The women at the Southbank Centre were weighing exactly the response Harman’s pink bus was supposed to head off. They were considering not voting at all. ‘There’s nobody to vote for,’ said one of them.

A tube train rumbled beneath us, or perhaps it was Emmeline Pankhurst spinning through the soil of Brompton Cemetery. Then again, Pankhurst overestimated the transformative power of suffrage. ‘It is perfectly evident to any logical mind that when you have got the vote, by the proper use of the vote in sufficient numbers, by combination, you can get out of any legislature whatever you want, or, if you cannot get it, you can send them about their business and choose other people who will be more attentive to your demands,’ she declared in 1913. Yet here we were, gearing up to mark the centenary of the Representation of the People Act and 86 years after full enfranchisement, still waiting to be fully enfranchised.

This proved to be the inescapable subtext of the whole evening. For all that James and Swinson and Creasy had won admission to the House of Commons, they had not thrived as their talent suggested they should. Swinson was a junior minister, Creasy held the equivalent position on the opposition benches. James served as a Parliamentary Private Secretary, two rungs below a junior minister.

If Westminster didn’t value them enough to put them at its top tables, the media helped to reinforce that view. I understood the reasons for this. After 30 years as a journalist, latterly a decade at TIME magazine, I was well aware that media companies – like political parties – were still far from closing the gender gap. Male cultures inevitably produce distorted and inadequate coverage of women. For female journalists, sexual harassment by colleagues or interviewees is an occupational hazard as routine and inescapable as a stiff neck from too much time at the computer. Pay and promotional structures value male staff over their female colleagues and, in admitting too few women to decision-making, maintain a male sensibility about which stories should be covered and how. This can be insidious – women receive less coverage than men and what they do often appears labelled ‘lifestyle’ – or it may express itself in hostility and mockery. Swinson gave an example of the latter during the WOW discussion: her observation during a parliamentary debate that boys might want to play with dolls mutated in the Sun’s reporting into a proposal to mandate boys to play with Barbies. New media also meant new challenges. Creasy had become the target of virulent Twitter trolls spewing rape and death threats, simply by virtue of being female.

The trio set out the problems of women in politics compellingly. They had some answers. Yet it was equally evident that they had little power to make change and little prospect of more power. So when Jude Kelly, the artistic director of the Southbank Centre and moderator of the event, invited the audience to volunteer proposals to speed gender equality, I found myself clutching the microphone.

I explained that when Jude conceived of WOW in 2009, she had recruited me to the founding committee. I talked about the sense of female community and commonality the festival always generates, and congratulated the MPs on demonstrating their spirit despite party political differences.

I continued: ‘I, like many other people, come to this election knowing that whatever the outcome, it will be disappointing. It would be so much more exciting – we would be spoiled for choice – if the three of you were the leaders of the parties.’

The audience whooped in agreement.

‘The questions you’ve all been asking this evening are about not only how we make progress but how we hold onto progress. So what I would like to do is invite anybody who wants to come to the bar afterwards or interact with me on Twitter to consider whether one way of doing this might be to actually found a women’s equality party, one that works with women in the mainstream parties that are doing the good things, and indeed with men in those mainstream parties who are doing the things that need to be done, but works rather in the way of some fringe parties that we’ve seen coming up to push [gender equality] so that it finally really is front and centre of the agendas of mainstream parties. At which point we’d happily dissolve our party, go away and leave the mainstream parties to what they should be doing.’

‘So that is my question. I will be at the bar afterwards.’

‘Are you buying, Catherine?’ asked Creasy.

I could have reduced that whole rambling, unplanned intervention to two observations: old politics was failing and its failure was creating room for change; mainstream parties had lost their core identities and were therefore primed to copy anything that looked like it might be a vote winner. If you build it, they will come.

The growth of the Green Party had provided mulch for green shoots in other parties. When the United Kingdom Independence Party started winning serious support, the other parties gave up challenging its anti-immigration rhetoric and started contorting themselves into UKIP-shaped positions. It wouldn’t be until the results of the EU Referendum the following year that we would begin to see the full consequences of the copycat syndrome, but it was already clear that UKIP didn’t need to be in government to transform Britain. The threat to women posed by a surging UKIP and the success of similar parties in other countries was also becoming evident. They represented a backlash against a whole range of values, including gender equality. ‘The European Parliament, in their foolishness, have voted for increased maternity pay,’ then UKIP leader Nigel Farage tweeted in 2010. ‘I’m off for a drink.’ Why couldn’t a women’s equality party steal from their political playbook to assert the opposite view? Why couldn’t a women’s equality party trigger copycat impulses in the established parties and finally push the interests of the oppressed majority to the top of the political agenda?

People enthused about the idea the moment the words came out of my mouth. They also assumed, to my alarm, that I was proposing to do something to make it a reality. Some followed me to the bar and yet more joined the discussion in the perpetual pub of social media. I returned home to an empty house and an empty fridge and before going to sleep left a message on Facebook to amuse friends who knew of my musician husband’s dedication to eating well. ‘Andy’s only been on tour for 24 hours and I’ve already had a sandwich for dinner. And started a women’s equality party.’ I added: ‘Want to join? Non-partisan and open to men and women.’

‘I’m in!’ replied the writer Stella Duffy almost instantaneously. ‘Me too,’ declared Sophie Walker, a Reuters journalist who could not anticipate just how deeply in she would soon find herself. By the next morning, the thread had lengthened considerably and all the responses were similar.

I called Sandi Toksvig, broadcaster, writer, comedian, and, in the pungent prose of a Daily Mail columnist, ‘a vertically challenged and openly lesbian mother’. She too was on the WOW founding committee and two weeks earlier we had talked at a committee dinner about how to channel the energy the festival always generated into transformative politics. We hadn’t discussed specific mechanisms, so I thought she might be interested to hear about my spontaneous proposal at the Women and Politics event. Her response wasn’t quite as anticipated.

‘But that’s my idea,’ she said. Each year she concocted a show called Mirth Control as a finale for WOW and for 2015 was planning to bring onto the stage cabinet ministers from an imaginary women’s equality party. She’d been on the point of ringing me with a proposition. ‘Darling,’ she said. ‘Do you want to be foreign secretary?’

The idea of someone with no Cabinet experience and a habit of making off-colour jokes becoming the UK’s premier advocate abroad made me laugh, but that was before Theresa May appointed Boris Johnson to the role. However both Sandi and I aspired to see more female secretaries of state.

Days after WOW’s glorious finale, we sat down together and lightly took decisions over a few beers that would disrupt our lives and many others. We decided to give it a go, try to start a party. We swiftly concluded we weren’t the right people to lead it. Sandi is the funniest woman in the world but her wit is a shield that conceals an enduring shyness. She would never have willingly put into the public domain details about her private life – she came out in an interview with the Sunday Times in 1994 – had she not faced twin pressures. Tabloids threatened to reveal her ‘secret’, and she felt compelled to campaign for lesbian and gay rights and equal marriage. Her revelation earned death threats that sent her into hiding with her young children. The last thing she wanted was more disruption. ‘Can we go home yet?’ she asks me, often and plaintively. It’s a joke but there’s always truth to Sandi’s humour.

We also feared we were too metropolitan, too media, to rally the inclusive movement we envisaged. For the party to be effective, it had to be as big and diverse a force as possible. That meant getting away from the assumption that the left had sole ownership of the fight for gender equality. It meant a commitment to a collaborative politics dedicated to identifying and expanding common ground, and that in turn demanded a serious effort to build in diversity from the start. That diversity had to include a wide range of political affiliations and leanings.

Sandi also realised she’d have to give up her job as host of the BBC’s satirical current affairs show, The News Quiz. It was a move her fans didn’t easily forgive. After the announcement, the ranks of my regular trolls swelled with angry Radio Four listeners venting their displeasure.

Even before Sandi’s public involvement, our meetings, advertised only on Facebook and by word of mouth, drew hundreds. From the first such gathering, on 28 March 2015, came confirmation of the party’s name. Some participants argued for ‘Equality Party’, but that risked diffusing the message while potentially reinventing the Labour Party. Others favoured Gender Equality Party as an easier sell to male and gender non-binary voters, but that had the ring of a student society in a comedic campus novel. Sandi has little patience for the discussion, which has continued to flare. ‘We just thought we’d be clear,’ she says. ‘We’re busy women and we didn’t really want our agenda to be a secret.’ ‘Women’s Equality Party’ is direct, unambiguous and produces the acronym WE, pleasingly inclusive if apt to spark toilet humour. Politics, as we would learn at first hand, involves compromise.

Speakers at that first meeting included Sophie Walker, later elected WE’s first leader by the steering committee that also emerged from that meeting. At the second meeting on 18 April we signed off on six core objectives: equal representation, equal pay, an education system that creates opportunities for all children, shared responsibilities in parenting and caregiving, equal treatment by and in the media, and an end to violence against women and girls. In June, our first fundraiser at Conway Hall in London sold out within hours. In July 2015, WE registered as an official party. October saw the launch of our first substantial policy document, compiled in close consultation with experts, campaigning organisations and grassroots support that already amounted to tens of thousands of members and activists. WE raised over half a million pounds by the year end. In May 2016 we secured more than 350,000 votes at our first elections for London Mayor, the London Assembly, the Welsh Assembly and the Scottish Parliament.

A month later, I encountered Boris Johnson’s father, Stanley, a former Member of the European Parliament, at the birthday gathering of another politician. ‘Catherine,’ he shouted across the room. ‘I heard some terrible news about you!’ The room fell silent, heads swivelled. ‘I heard you’d become a feminist!’ Later that evening I talked to a Labour peer who berated me for splitting his party. This was a feat Labour was managing without external help. At the same event, prominent members of Labour and the Conservatives confessed they’d voted for us. Westminster was no longer patronising and dismissing us, but it wasn’t yet sure what to make of us either.

WE’s second year was more eventful still. Our first party conference in Manchester in November 2016, attended by 1,600 delegates, adopted a raft of new policies including a seventh core objective, equal health, and ratified an internal party democracy devised to give branch activists a guaranteed presence on decision-making bodies and ensure real diversity on those bodies. We ran campaigns that had significant impact such as #WECount – mapping sexual harassment, assault and verbal abuse directed against women. Tabitha Morton ran for WE in the first race to be Metro Mayor of the Liverpool’s city region, spurred to do so because the region had no strategy for combating violence against women and girls, despite having the UK’s highest reported rates of domestic violence. After the election she was asked by the winner, Labour’s Steve Rotheram, to help him to implement the strategy she made central to her campaign.

We began detailed work with other parties too. The Liberal Democrats asked for help in drafting legislation to combat revenge porn – the disclosure of intimate images without consent. Several parties and politicians opened conversations with us about much closer cooperation, including the possibility of alliances and joint candidacies.

We didn’t expect to road-test these ideas before the general election scheduled for 2020. Our plan was to build up our war chest ahead of that deadline and gain experience and exposure by participating in the May 2017 local council elections and the contest for the newly created post of the mayor of the Liverpool region. Then, while those races were still under way, May called her snap election.

We fielded five candidates in England and one apiece in Scotland and Wales, on a radical and innovative platform that understood social care not as an unfortunate expense but the potential motor of the economy, and proposed fully costed universal childcare. Large chunks of our original policy document resurfaced in the manifestos of other parties. In the Yorkshire constituency of Shipley, Sophie Walker stood with the backing of the Green Party, in a progressive alliance. The joint WE–Green target was the Conservative incumbent, Philip Davies, a prominent antifeminist. We hoped Labour might join us – they had largely abandoned hope of the seat after serial defeats – but instead they chose to run and directed more of their energy against us than Davies. This reflected both Labour’s belief that it owns feminism and an overheated partisan culture that rejected all opportunities for electoral pacts across the UK.

Labour, like the Conservatives, continues to back the first-past-the-post electoral system even though it has been shown globally to exclude women and minority perspectives. Both Labour and Tories presented the election as a binary contest. Our candidates heard the same message from the left and the right: stand aside, women. In the final days of the campaign, our offices received hundreds of abusive phone calls and a death threat to Nimco Ali, our candidate in the London constituency of Hornsey and Wood Green. The letter, scrawled in capital letters and larded with Islamophobia, was signed ‘Jo Cox’. During Jo’s first and only year serving as a Labour MP, she had made a significant impact not least in advocacy for women before her brutal murder in June 2016. Nimco knew her as did I. This wasn’t the first time someone had tried to silence Nimco, who arrived in the UK as a child refugee from Somalia, survived FGM and co-founded Daughters of Eve, a non-profit organisation campaigning against it. The next day she and I went out canvassing together. I watched her, decked out in WE colours, utterly recognisable, meeting as many people as possible. She and our other candidates didn’t win seats, but they were all winners.

This book isn’t intended as a history of the party. These are still early days for us – and could be the end of days too. The challenges to the survival of our upstart initiative remain acute in a political system designed, like zombie Johansson’s breasts, to smother movement in the lower tiers. These challenges are also shifting and shape-changing with unprecedented speed since the UK began disentangling itself from the European Union and tangling instead with the demons the process is unleashing. The Referendum was conceived to reconcile internal strains within the Conservative Party, but did no such thing. Labour’s fault lines are at least as deep; things fell apart, the centrists could not hold on. As Labour’s left, resurgent under Jeremy Corbyn, battled for control of the party, fugitives sought a haven in the Women’s Equality Party. Some of them dreamed of repositioning us. ‘What I’d like is for the Women’s Equality Party to remake itself as the Equality Party,’ wrote the novelist Jeanette Winterson in the Guardian. ‘It’s a relevant name, a powerful name, and naming matters. I’d like to drop Labour and New Labour as words that don’t mean anything anymore. If you still needed proof of that after the last election, Brexit just gave it to you.’

We did consider changing the name but most of us opposed the idea of dropping ‘women’ from our brand – that would mean becoming like all other parties and relegating women’s interests. And Brexit posed a danger to women as the process of decoupling raised questions over rights and protections anchored in Europe and guaranteed by Europe. When Parliament began considering legislation to trigger the Brexit process, an amendment we devised with the Greens drew the widest cross-party support of all such initiatives. Our vision was more relevant than ever. Whenever we shared it, we won new support, new members. Our first problem was, and remains, how to get our message out on meagre resources, in a media culture pre-programmed to diminish the importance of that message. The second problem is how to raise the money to keep going.

So a monograph on the Women’s Equality Party would be premature. I will, however, share insights from the process of starting the party. Journalists often suffer from the delusion of being intimately acquainted with the world. Work had taken me to six continents, war zones and pleasure domes, to interviews with dictators and democrats. It’s quite a lot like being married to a rock musician. You enjoy Access All Areas: ringside seats, freedom to roam backstage. These experiences foster understanding, but they don’t make you part of the band. As a journalist, I imagined I understood politics. As a journalist-politician-whatever, I now understand how imperfect that understanding was.

But my primary aim in writing Attack of the 50 Ft. Women is not just to mine lessons from the recent past and present, but to think about Equalia. What can today’s world tell us about the way to this promised land and what we might find when we get there?

In The Female Eunuch, the text that woke me and many others to feminism, Germaine Greer quoted Juliet Mitchell’s 1966 essay, Women – the Longest Revolution: ‘Circumstantial accounts of the future are idealistic and, worse, static.’ This is both right and wrong.

No such account makes sufficient allowance for the impact of quakes, natural or of human origin, or the intended consequences that flow even from planned events. Technology is shaking up our lives in ways no seer foresaw (though science fiction writers came close to predicting whole chunks of it). How, for example, can we talk about gender in the future workplace if the workplace – if work itself – might disappear?

The answer cannot be to avoid such discussions, but to recognise the limits of our knowledge and imaginations and to try to expand both. Politics is all about shaping the future, yet political movements succumb too easily to the Happily Ever After syndrome. Gender equality advocates are no exception, focusing on the big, fat, equal wedding of genders, the moment equality is reached, and not what lies beyond. Confetti drifts and then the picture fades.

Knocking on doors for the Women’s Equality Party has proved revealing on that issue and, on occasion, literally. A resident of a Southwark tower block responded cautiously to my knock: ‘Who is it?’ ‘I’m here about the elections.’ ‘Electricity?’ In evident alarm, perhaps fearing I had come to cut his energy supply, he threw open the door, naked.

Campaigning also uncovered a generational split in male attitudes. Men in their fifties, finding WE canvassers on the doorstep, often respond ‘I’ll fetch the wife’. Younger men engage directly. We don’t need to explain this is a party for them, pushing a platform that will also benefit them.

That is encouraging; so too is the enthusiasm we encountered. People have told us they had literally danced when they heard about WE. But from the start they also asked difficult questions that we were already grappling with, both personally and as a party. Would gender equality encourage other kinds of equality? Did we want an improved version of our current society – gender equality within existing structures – or something more radical? How much change might be achieved through nudging? In what circumstances might prohibition or coercive legislation be necessary?

You can see why people would shy away from Equalia if they imagine it to be a brave new world that, like Aldous Huxley’s addled dystopia, requires a sublimation of the individual to a supposed greater good. You can see why they might lack enthusiasm for building Equalia if they sense that it will simply enshrine old injustices within a new pecking order. Would the new race of 50-foot women create a fairer system or form a new elite?

If only we could poke around Equalian homes and businesses, check what’s on the telly and in the news, find out how people are having sex and if anyone is selling it, taste the air to verify that it’s cleaner, and confirm that the shadows of conflict have receded. If only we could find out who does the dishes or the low-paid work in Equalia and whether such work is more highly valued. Will a society that allows everyone to take up as much space as they like produce giants, or might the absence of adversity diminish creativity, or obviate the need for ingenuity? We don’t even know what gender would mean in a society freed from gender programming. So how do we begin to answer questions so fundamental, not just to the Women’s Equality Party, but to everyone affected by the global imbalance between the sexes? And that’s all of us.

The ambition of this book is just that – not to answer these fundamental questions but to begin to answer them. There are clear limits to how definitive any such inquiry can be, not only because of the paucity of hard information, but because of the confines of my own experience. I am a product of my own background and socialisation, of a particular confluence of genes and influences, of luck – or privilege – and half a century of racketing about the planet. For this book I travelled as far as time and resources permitted, interviewed as widely as possible, read and kept reading, thought and kept thinking. I needed to learn in order to find out how much I didn’t know. The Equalia I describe, and the pathways I discovered, are located in the cultures that produced me. It may well be that the routes and outcomes look different in other hemispheres.

My quest took me to Iceland, the nation that comes closest to Equalia, and to countries and continents that have made less progress on gender equality, to ascertain the factors and people promoting or retarding change. Under Angela Merkel’s Chancellorship, Germany has become a better place for women – yes, even for the women of Cologne. Is she the kind of giantess we need, a 15-Meter Frau, or is she to blame for Germany’s current political turbulence? For now it’s May every month in Downing Street but this looks less like a sea change than proof of the so-called glass cliff, the phenomenon first identified by researchers at the University of Exeter that sees leadership opportunities open up to women at times of crisis when the odds against successful leadership peak. If Merkel and May are still in office by the time you start this book, they might not be by the time you finish it, though Merkel is a great survivor. And what should we make of Hillary Clinton’s fate and the rise of Trumpism and related strains of populism in Europe? These signal fresh challenges for women and minorities and to any consensus on gender equality. In France this movement is led by a woman, Marine Le Pen, who in May 2017 made it through to the second round of the country’s presidential elections. Yet the first day of Trump’s presidency also triggered the biggest women-led marches in history, with 3.5m protesters on US streets and millions more in 20 other countries determined to resist the rising world order.

We will survey the predictable changes heralded by science and technology, and by global shifts in power and population. China’s growth is endangered by the legacy of a one-child policy within a Confucian culture that values boys more than girls and, in acting out these preferences, has ended up with a surplus of discontented single men. India has 43 million more men than women. Rwanda’s population tilts in the other direction because genocide killed off scores of men. It now ranks higher than Iceland, indeed highest in the world, on female representation in politics. So, is it a paragon of gender equality?

We’ll examine the media, its power and potential. We’ll go to Hollywood and Facebook. We’ll visit citadels of privilege and ghettos of oppression. We’ll talk to experts, leaders, people in public life and in their most private pursuits. The personal is political and for that reason let us start this journey in that most personal of spaces, at home.

Please join me at my kitchen table.