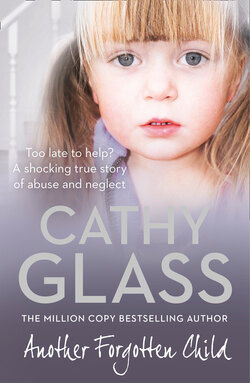

Читать книгу Another Forgotten Child - Cathy Glass, Cathy Glass - Страница 9

ОглавлениеChapter Five

Severe Neglect

‘You’ll like the water here,’ Lucy said, continuing with her philosophy that things were different and better in foster care.

‘No, I won’t,’ Aimee said, folding her arms and sulking.

‘I’m going to do my homework,’ Paula said, and escaped to her bedroom.

‘Come on, I’ll show you the new tiles I put in our bathroom,’ I said to Aimee with excitement out of all proportion to my first attempt at tiling.

Sufficiently intrigued, she finally slid from her chair at the dining table and followed me upstairs and to the bathroom, where I pointed out the blue and white tiles around the bath. ‘They’re nice,’ she said, with genuine admiration.

‘Thank you,’ I said.

‘We have tiles in my bathroom,’ Aimee said, ‘but they’re dirty and have green stuff growing on them,’ which I assumed to be mould.

‘Well, as you can see ours are all new,’ I said. ‘No nasty green stuff here. Now, would you like a bath or a shower? What did you have at home?’

‘Nothing,’ Aimee said, her face setting again. ‘I don’t have anything.’

I thought she must have had some sort of wash sometimes, so relying on the closed choice I said again: ‘Bath or shower? You choose.’

She didn’t answer but refolded her arms more tightly across her chest like a grumpy old woman. ‘OK, I’ll decide for you, then,’ I said. ‘I’ll run you a nice warm bath.’

Aimee said: ‘I want a shower.’

‘Fine. You can have a shower,’ I said. ‘Undress while I set the shower to the right temperature.’ Aimee was not old enough to be left alone to adjust a shower she’d never used before, so, turning my back on her to give her some privacy, I switched on the shower to a medium temperature.

As soon as the water began spurting from the showerhead Aimee squealed from behind me. ‘I ain’t having that on me!’

I switched off the shower and turned to face her. So far she’d only taken off her navy jumper, which was filthy, to reveal an equally filthy T-shirt. ‘Aimee,’ I said carefully, ‘you need to have a shower or a bath tonight. Then once you’re clean you’ll be able to watch some television. It would be a great pity if you lost television time on your first night, wouldn’t it?’ This may have seemed harsh but Aimee was used to having her own way and I could see how determined she could be. For hygiene’s sake alone she needed to have a bath or shower; her skin and clothes were filthy and she smelt. Also if I didn’t start to put in place a routine and boundaries now it would become more difficult the longer I left it.

‘Can I watch me telly in bed?’ Aimee asked.

‘Once you’ve had your bath, yes,’ I said. Not blackmail but positive reward.

‘I’ll have your bath, then,’ Aimee said, scowling.

‘Good girl.’ I turned to the bath and switched on the taps, adjusting the temperature as the water ran. But by the time the bath was ready Aimee still hadn’t undressed and seemed to be waiting for me to do it for her. ‘Take off your T-shirt,’ I encouraged.

‘Can’t,’ Aimee said, not attempting the task. ‘You do it.’

‘Aimee, you are eight years old, love. I’m sure a big girl like you can undress herself.’ Children are usually taught self-care skills by the time they’re five and go to school, but Aimee shook her head.

‘I’ll help you,’ I said. ‘But I would like you to learn how to dress and undress yourself. How did you manage to change for PE and swimming at school?’ For I knew the teachers wouldn’t have undressed her.

‘Didn’t do them,’ Aimee said.

‘What, you never did PE or swimming?’

‘No.’

I was sure Aimee must be wrong – physical exercise is an essential part of every school curriculum – but I’d mention it the following day when I took Aimee to school. Now I began easing up her T-shirt and showing her how to undress. ‘Like this,’ I said. Aimee raised her arms cooperatively but had no idea what to do next.

‘Who dressed you at home?’ I asked.

‘Mum.’

Underneath the T-shirt was an equally dirty and torn vest. ‘You like your layers,’ I smiled. ‘Aren’t you hot with all this on?’ The rest of us wore one layer in our centrally heated house.

‘It’s cold at home,’ Aimee said. ‘What makes your house hot?’

I didn’t answer, for having taken off Aimee’s vest I was now staring at the small bruises dotted all over her chest. I stepped around her so I could see her back and that too was covered in the same small bruises, as were her arms and neck. The bruises were all roughly the same size, small and round, about the size of a small coin. They were in various stages of healing: some were old and faded while others looked new.

‘How did you get all these bruises?’ I asked carefully, pointing to the ones she could see on her arms and chest.

‘I fell,’ Aimee said. ‘I keep tripping over things.’

It was possible the bruises were a result of falling, I supposed. Some children are accident prone, and it’s often the overweight children who aren’t used to physical activity and have never developed good coordination and balance as more active children do. It was possible, yet there was something about the size and shape of the bruises that I couldn’t identify and unsettled me. The bruises didn’t require medical attention, but I’d obviously make a note of what I’d found in my fostering log and then tell Jill and Kristen the following day.

‘Sit on the floor and take off your socks now, good girl,’ I said to Aimee, sure she could do this simple task without help. She did as I asked and sat down, and then very clumsily managed to pull off both her filthy and holed socks. ‘Now step out of your joggers,’ I said, testing the bath water with my hand. ‘They’re easy to take off. You just pull them down.’

Aimee yanked down her joggers and stepped out of them, to reveal more bruises running down both legs, from her thighs to her ankles – there were even some bruises on her feet. Most of the bruises were the same size and shape as those on her body and arms – round and small – although there were some larger ones on her knees and shins, consistent with falling over.

‘How did you get all these?’ I asked.

‘I fell over.’

She stepped out of her pants to reveal more small round bruises on her buttocks. ‘And the ones on your bottom?’ I asked. ‘How did you get those?’

‘Same,’ Aimee said, tossing her pants on top of the pile of smelly rags that were her clothes. She stood at the side of the bath, making no attempt to get in.

‘Get into the bath while the water is nice and warm,’ I said.

She reached out to my hand for me to help her and I steadied her while she climbed into the bath. Then she stood looking at me.

‘Sit down,’ I said.

‘What, in the water?’ Aimee asked.

‘Yes.’

‘Why?’

‘So you can have a bath and wash all over.’

Very gingerly and slowly Aimee began to lower herself into the bath, and as the warm water lapped against her skin she gave a little sigh of pleasure. ‘This is nice,’ she said.

‘Good,’ I said, relieved. I passed her a new sponge and fresh bar of soap. ‘Now rub the soap on to the sponge and then all over your body.’

But she just sat there with a smile on her face, enjoying the feel of the warm water without actually washing, despite my further encouragement.

‘This is nice,’ she said again. ‘I like the warm water.’

‘Aimee,’ I said suspiciously, ‘have you ever had a bath before?’

‘No.’ She grinned sheepishly.

‘So did you usually have a shower at home?’

‘No. All the water was cold and I don’t like cold water.’

‘Wasn’t there any hot water in your flat at all?’ I asked, aware that this was not as uncommon in poor homes as one might think.

‘No,’ Aimee said, shaking her head.

‘So you never had a hot shower or bath?’

‘Never. I stood in the kitchen and Mum used one of those.’ Aimee pointed to the face flannel draped on the rail at the side of the bath. ‘But the water was cold, so I didn’t like it.’ From which I deduced that Aimee had been given a stand-up wash in cold water and had never had a bath or shower in her life.

‘Did your social worker, Kristen, know there was no hot water in your flat?’ I now asked.

‘Of course not!’ Aimee said, surprised at my ignorance. ‘Me and Mum told her the meter had just run out and we were going to get some more tokens, but we never had the money.’ She giggled at the deceit she and her mother had perpetrated on the social worker, and not for the first time since I’d begun fostering I was shocked by the ease with which a social worker had been duped.

‘Why didn’t you tell Kristen there was no money for hot water?’ I asked. ‘She could have helped you.’

Aimee looked at me, confused, and I guessed it was because she wasn’t used to hearing that a social worker could help. So often parents view social workers as the enemy.

‘Mum said if we told Kristen I would be taken away and put in care like my brothers and sisters,’ Aimee said. ‘Mum said I wasn’t to tell her about the water. There were lots of things I couldn’t tell Kristen.’ She suddenly stopped.

‘Like what?’ I asked gently, lathering the soap on to the sponge for her.

‘Nothing,’ Aimee said. ‘They’re secrets and I’ll get shouted at if I tell.’

‘Who will shout at you?’ I asked.

‘No one,’ Aimee said, clamming up.

‘All right. But sometimes it helps to tell a secret. Bad secrets can be very worrying, not like the surprises we have on our birthdays. When you feel ready to tell me I will listen carefully and try to help,’ I said, although I knew it could be months, possibly years, before Aimee trusted me enough to tell me. I also knew that ‘secrets’ when the child had been threatened into not telling always involved abuse.

The bath water turned grey as Aimee washed; indeed the water was so dirty that I drained the bath and refilled it with fresh water. I explained to Aimee that I would just comb her hair before bed and then wash it in the morning after the lotion had done its job properly. I helped her out of the bath, wrapped her in a towel and left her to dry herself while I went to the ottoman in my bedroom for some clean pyjamas that would fit her. When I returned she was still standing with the towel around her, having made no attempt to dry herself.

‘Come on, dry yourself,’ I encouraged.

‘No, you do it,’ she said.

‘I’ll help you. But you need to learn to dry yourself at your age.’ I showed her what to do – how to pat and rub the towel over her skin – but I didn’t do it for her. I guessed that the reason Aimee didn’t know how to towel dry herself was that, never having had a shower or bath, she’d never had to do it. This level of neglect – of even the most basic requirements – is a form of child abuse.

After about ten minutes, and with a lot of encouragement, Aimee had dried herself. ‘These should fit,’ I said, and held out the nearly new clean pyjamas I kept as spares for such an emergency.

‘Not wearing them!’ Aimee sneered, pulling a face and shrinking from the pyjamas I held. ‘They’re not mine.’

‘They’re yours for now,’ I said. ‘Then we’ll buy you some new ones after school tomorrow.’

‘Ain’t wearing them,’ Aimee said again, her face setting. ‘I want me own.’

‘You haven’t brought any with you,’ I reminded her gently.

‘Yes I have!’ Aimee snapped, jutting out her chin. ‘They’re in me bag downstairs.’ I now remembered the threadbare and filthy pyjama top Aimee had tipped on to the dining table when she’d been looking for her biscuits.

‘There was only the top, love, no bottoms, and it needs washing.’

‘I want me top,’ Aimee demanded rudely. ‘I’ll wear me knickers with it, like I do at home.’ She made a move to retrieve her knickers from the pile of filthy clothes she’d taken off before her bath.

‘No,’ I said firmly. ‘You can’t wear those pants. You are nice and clean now. If you put on those you’ll be dirty again. Wear these pyjamas for now and I’ll wash your clothes tonight, and then you can have them in the morning.’ I knew children were often attached to their own clothes and felt secure wearing them when they first came into care, and I always tried to use them whenever possible. But I was also aware that dirty clothes can harbour and transmit parasitic diseases such as scabies and ringworm; not only to Aimee but to the bed linen and anyone else who came in contact with the infected clothes. ‘Put on these,’ I said firmly, placing the pyjamas into her arms. ‘You dress while I put your things in the washing machine.’

Before she had a chance to refuse I’d scooped up the ragged clothes and was hurrying downstairs and into the kitchen, where I threw the clothes in the washing machine. I took the pyjama top and knickers from the plastic carrier bag and put those in too. Then I added a generous measure of detergent and set the machine on a hot wash. I would have liked to have washed Aimee’s teddy bear, which was in the plastic carrier bag, but I knew Aimee would need that tonight for security. I thoroughly washed my hands and then returned to the bathroom, where Aimee had made a good attempt to dress herself. The pyjama top was on back to front but that didn’t matter.

‘Well done. Good girl.’ I smiled, and instinctively went to hug her, but she drew back.

‘Don’t you like hugs?’ I asked.

‘Not from you,’ she said defiantly. ‘You ain’t me mum.’

‘I understand. Let me know when you’d like a hug.’

‘Never!’ Aimee scowled.

Mindful that the evening was quickly passing and I would need to get Aimee up early for school the following morning, I continued with the bedtime routine. Now she was clean and in her pyjamas I gave her a new toothbrush and tube of toothpaste and told her to squeeze a little paste on to her brush and clean her teeth well. It soon became obvious that Aimee didn’t know how to take the top off the toothpaste, let alone squirt some paste on to the brush, so I did it, showing her what to do so that she’d know for next time. ‘Now give your teeth a very good clean,’ I said, handing her the toothbrush.

She put the toothbrush into her mouth, sucked off the paste and swallowed it. ‘Ahhh!’ she cried, spitting the rest into the bowl. ‘You’re trying to kill me!’

‘Aimee, love,’ I said stifling a smile, ‘you’re not supposed to eat it. Just brush it over your teeth and then spit it out. Didn’t you have toothpaste at home?’

Aimee shook her head.

‘Didn’t your mum and dad brush their teeth?’

‘Mum ain’t got many teeth,’ Aimee said. ‘And Dad takes his out and puts them in a jar.’ From which I gathered that both her parents had lost most of their teeth and her father had false teeth. Her parents were only in their mid-forties but one of the side effects of years of drug abuse is gum disease and tooth loss.

‘Do you know how to brush your teeth?’ I asked Aimee. ‘Did you brush them at home?’

Aimee shook her head.

Horrified that a child could reach the age of eight without regularly brushing their teeth, I took the toothbrush and said, ‘Open your mouth, good girl, and I’ll show you what to do.’

There was a moment’s hesitation when Aimee kept her mouth firmly and defiantly closed; then, thinking better of it – perhaps remembering her parents’ lack of teeth – she opened her mouth wide. ‘Good girl,’ I said, and I began gently brushing. Many of her back teeth were in advanced states of decay or missing. As I gently brushed Aimee’s remaining teeth, showing her how to brush, her gums bled – a sign of gum disease.

‘Did you ever see a dentist?’ I asked as I finished brushing and Aimee rinsed and then spat out.

‘Yeah. And I ain’t going back. He put a needle in me mouth so he could pull me teeth out. I’ll end up like me mum if he keeps that up.’ So that I thought at least some of Aimee’s missing teeth had been extracted by the dentist because of advanced tooth decay. The poor kid had really suffered and my anger flared at parents who could so badly neglect their daughter; but then drug-addicted parents would be more concerned with obtaining their next fix than making sure their daughter brushed her teeth.

Before we left the bathroom I told Aimee I wanted to fine-tooth comb her hair and I asked her to lean over the sink while I did it. She didn’t object and ten minutes later the white porcelain basin was covered with hundreds of dead head lice. The lotion would stay on overnight so that it could complete its job and I would wash it off in the morning. When we’d finished I praised Aimee for keeping still.

‘Will I have friends at school now?’ Aimee asked.

‘I’m sure you will. Why? Has there been a problem with your friends?’

‘I ain’t got none,’ Aimee said bluntly. ‘The other kids call me “nit head” and “smelly pants”. When I try and play with them they run away.’

‘Well, not any more,’ I said, my heart going out to her. ‘Now you’re in foster care you will always be clean and have lots of friends.’

‘Promise?’

‘Yes.’

‘And you never break a promise?’

‘Never.’

‘Cor, I’m looking forward to going to school.’