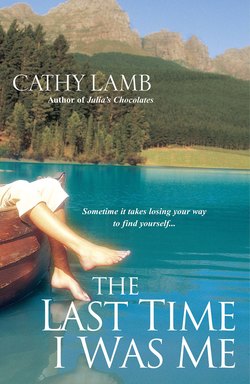

Читать книгу The Last Time I Was Me - Cathy Lamb - Страница 11

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

CHAPTER 5

ОглавлениеAnger management class is located in Portland, so I had to drive about fifty minutes west to get there. I go from towering fir trees, homes scattered along a river, and a main street that moves about as fast as melted taffy, to a city filled with rushing people, darting cars, skyscrapers, and a bunch of preposterously high and mind-numbingly scary bridges spanning the Willamette River.

I cried my way into the city, because I felt like it, shoulders shaking, sounding quite like a dying warthog. How I am relishing my nervous breakdown!

I slowed way down when I went over a bridge. The car behind me honked and the driver flipped me the finger, but I ignored him, eyes straight ahead, not looking down, down, down into that river below filled with who knew what kind of eight-headed human-eater or monster shark. (I do not like heights or bridges.)

By the time I reached the Diamond District my face was red and blotchy and pale, my lipstick smeared. My mascara had trickled across my face and it looked as if dead ants had been buried in shallow graves across my cheekbones. I am a multicolored freak, I told myself, looking in the car mirror, a multicolored freak.

I cleaned up as best as a crybaby can, running my fingers through my gold curls and adjusting my clothes. I was wearing jeans, a purple, lace-lined camisole, a lavender-colored silk blouse, some cool gold hoop earrings, and about three inches of bracelets. I also wore black heels with a strip of lavender on the toe that exactly matched the camisole. They are completely cool.

Anger management class was located in a building that used to be a warehouse. In fact, this whole area of town, dubbed the Diamond District, used to be an industrial wasteland, according to Rosvita. Lots of rundown factories, warehouses, old stuff. But the location was too cool-close to the river, to downtown, to shopping and work-to stay that way.

So one by one the factories were either bulldozed or converted and glass-walled buildings shot up. But the Diamond District had not yet been perfected, which probably lent to its appeal. Streets weren’t always paved right, tired factory buildings butted up to new, sleek structures, and there was a bit of a rough edge to it. I found parking near the address, crossed one street with potholes the size of Denver, and dodged a huge dump truck and an earth-mover.

I looked at the address in my hand again. The anger management woman had told me that when I could smell beer, I was there. I could smell the beer. In fact, as I circled the building, I knew I was looking at, and smelling, a brewery.

The temptation was almost too much for me. Beer and me have a long and golden and messy history and to slug one down right at that moment, or three or four, had vast appeal. I had heard that Oregon was home to a bunch of brothers who knew their beer, and I was anxious to taste the products of those bros.

Two things held me back: One, I had been told to be prompt or else. Two, I was driving home. I have often been drunk in the last twelve years of my life, but I have never, ever driven after drinking.

It’s like my other rule: I have been a bit slutty at different times in my life, and the sex left me colder and lonelier and more withered inside than I was before, but I don’t mess with anyone else’s man.

Those are about the only two hard and fast rules I have, but they’ve worked for me thus far.

I circled the building, trying to banish the thought of pouring gold beer down my throat, and looked for the double doors. Finally, I saw them. Painted green with a gold sign to the left that said, EMMALINE HALLWYLER, COUNSELOR.

The entry was dark when I stepped in, but I saw stairs to my right and started to climb. The building, by my deductions, was probably one hundred plus years old with dust the same age, and dark as a caveman’s cave.

I reached one landing and saw another gold sign that said EMMALINE HALLWYLER, COUNSELOR, and pointed up. This led to a hallway painted bright white. The white paint was thick, like frosted icing. At the end of the hallway, there were black and white photographs on both sides. All featured close-ups of people in the throes of one acute emotion or another: Joy. Surprise. Grief. Despair. Exhaustion. Depression. Panic. There must have been thirty pictures, all framed in black.

The sign above the photographs said, PHOTOS TAKEN BY EMMALINE HALLWYLER. Super. She could photograph me when I was screaming, my face puffed like a red marshmallow, my mouth twisted like a red snake. I glanced at my watch. It was exactly 12:00.

I was prompt. I looked like hell, but I was prompt and had not succumbed to golden beer, and guzzling.

I turned one more corner and faced about twenty stairs.

When I reached the top of the stairs, I had to blink. Light shone from all corners of the huge room from a multitude of windows. The floor and the walls were bright white, too. In one corner of the room, there were five red boxing bags suspended from the ceiling.

In another corner, there looked to be a craft area. It was filled with glue and ribbons and tape and Styrofoam and wood. Scraps of metal, cardboard, egg cartons, and piles of stuff that looked like it came straight from the dump.

In the third corner there was a number of huge pillows. A large sign above the pillows labeled it as the SCREAMING CORNER.

In the fourth corner was a piano, a set of drums, guitars, and other musical instruments. I saw a violin. My heart squeezed real tight over that violin.

In the middle of the room were seven beanbags. They looked like a rainbow-purple, blue, green, yellow, orange, red. In the center of the beanbags was a bigger-sized black beanbag and in the center of the black beanbag sat a woman.

Now, I was expecting Emmaline Hallwyler to be about as wide as the Amazon jungle, with perhaps a black panther curling behind her and a venomous snake wrapped around her neck.

There was no black panther, no venomous snake, and Emmaline Hallwyler was positively tiny. I could tell because when I looked in her direction she stood up.

She was dressed all in white. White pants, white blouse, white high heels. It would have looked ridiculous on anyone else. Me, I would have looked like a gawky, temperamental angel who had had her wings taken away for punishment for some lousy offense.

Emmaline, with her brown bob of hair and huge brown eyes and finely cut features, looked positively elegant. I would later learn that under the fragile elegance was a she-demon quite capable of knocking heads together and ripping people down to the size of pesky mice.

“Do not move.” She said this with great authority.

I hate when people order me about, but I obeyed. This class was court-ordered, after all, and with a good report maybe I could keep from getting too screwed with the judge.

I didn’t move.

She stared at me. I stared back. When you are used to working with male, egotistical advertising pricks who believe the earth was made for the pleasure of them and their dicks and everyone else is squash vermin, you get in the habit of not being intimidated.

“I can feel your anger,” she told me, her voice ringing off the walls.

“Gee, what are you, psychic or something?”

“Stuff it, Jeanne. Your hostility is like burning hot rocks.”

“Gee again. That’s why I’m here. Anger and hostility. Can I move now?”

“No.”

I waited. Perhaps she was taking time to feel my hostilic anger.

“You’re barely hanging on.”

“No shit.”

“No, there is no shit,” she snapped. “None at all. You’re a repressed chick. You’ve dug yourself into a psychological cave by not allowing your emotions out. It’s all your fault.”

I paused at that one. My fault?

“Your pain and anguish have shaken you like an internal earthquake and you’ve grabbed hold of your loss in a deathlike grip. Fury is the emotion that comes out when people are scared. You let your problems run your life by packing them away in your anger. They stay because you won’t examine them and throw them out. When the problems grew and grew to unimaginable heights, like a mountain range, you hid from them, convincing yourself you could handle life, no problemo. But you hit a crisis valley and you were shoved right off a cliff and your life exploded.”

Well, she certainly boiled things down quickly, didn’t she? And in such geographical terms, too! “You’re a genius,” I told her. “Brilliant. May I come in now? That purple beanbag is looking pretty good to me.”

I started to walk toward her.

“Stop.”

I stopped. Sighed. This was a bad day.

“Hit,” she said.

“I’m sorry?”

“Hit.”

“Should I hit you?” I asked. “How hard?”

She glared and pointed at the punching bags hanging from the ceiling like giant bloodred splotches.

“Hit the bags until your anger is gone.”

I dropped my purse on the ground.

“That would take days. No, it would take months. No, it would take years. Will I be charged by the hour? And, if you go home to go to bed while I’m still hitting, do I still get charged?”

She crossed her arms across her chest. “Start. Hit. Now.”

I shrugged. I would pretend it was Slick Dick’s face. I really missed my mountain bike.

“Stop.”

I eyed the she-demon. “Whatever could it be now?”

“Take off your shoes. Shoes carry bad energy with them. All of our anger and frustration rolls right down our bodies to our feet and our feet expel that impotence and blackness like an upside-down volcano into our shoes. Leave the shoes, leave the lava and flying rocks of your past behind.”

I glanced down at my black and lavender heels.

I have a tragic relationship with my vast shoe collection, this I know. My shoe obsession started after I lost Johnny and Ally. Before that, Johnny and I had worn tennis shoes, hiking boots, or flip-flops, spending as little as possible because we were broke college students. Those shoes were, and always will be in my mind, the best.

But when I started a new job at an advertising agency about six months after they died, still believing that the pain of my overwhelming grief could stop my heart from beating at any second, I bought a pair of new black heels. The heels distracted me when I got stressed, so I bought a pair of red heels, next a taupe pair, and soon I got daring and slightly hysterical and bought four-inch-high pink heels with little red daisies on the sides.

The heels distracted me when I thought of Johnny and Ally. I know that sounds bizarrely shallow, but I had nothing to hold onto. I would think, “I want to die I want to die I want to die,” and I’d peek down at my bright red or striped or polka-dot heels and I’d start thinking of which pair of shoes I wanted to be buried in and for some reason, that shook me out of my severe and pervasive depression a bit.

At least enough to go on living through the next hour or until I could get to a mall and distract myself again.

“Take off the volcanoes of anger, Jeanne,” Emmaline ordered. “Get away from the hot lava flow of frustration.”

I swallowed hard and started feeling hot and very insecure at the same time, but I flicked off the heels. I stood flat-footed and felt more and more vulnerable by the second, a whole bunch of emotions I didn’t want to have to deal with running into my head at breakneck speed.

I did nothing in front of the red blob, for long minutes, but the blob morphed into everything I was mad about. I whacked that thing and darn near broke my wrist.

“Don’t be a wimp.” I had not realized Emmaline was right in back of me. “Hit it again.”

I hit it again.

“Again.”

This was not too bad. I hit it again and again, like a boxer, using both hands.

“Use your feet,” Emmaline ordered.

I kicked it with my feet.

“Kick the negatives out of your soul,” she insisted. “Kick those soul-crushing negatives from your kidneys and liver and pancreas and prostate, and let it flow from your feet.”

I stopped at that. “I don’t have a prostate.”

“Whatever,” she boomed. “Kick the prostate you don’t have outside of your body.”

I focused on the bag again, then kicked the negatives out of the prostate that I didn’t have.

“Use your butt.”

I was sweating now but feeling better. I dropped my purple silk blouse to the floor, and charged backward into the bag. It swung back and almost knocked me over. I hit it again, it swung back and into me, back and forth we went. It became my red-blob enemy.

“With your elbows,” Emmaline called out, her voice strident now. “Again with your fists.” I swung and swung. Sweat dripped off my forehead. This went on for way too long. Hit, hit, hit. Sweat.

“Stop.”

I sank to the floor, panting. I wondered if she had decided if she liked me or not. I decided I didn’t care. Slick Dick’s face had been beaten to a mangy pulp and that’s all I cared about.

“Come to the center of the room, the center of peace.”

I struggled to my feet, followed obediently behind her, much like a wussy dog.

“Sit in the purple beanbag.” I was too wiped out to argue. I sat.

She settled in the black one.

“Let’s get rid of the black mold over your heart,” she said, her eyes narrowing. “It’s destroying you.”

Mold over my heart. A sumptuous thought. I needed a beer. I needed many beers. Maybe after this little session I would drop into the brewery and drink straight from a keg lying on my back.

She reached out and ran a finger across my forehead and studied my sweat. For fun, I ran a finger across my forehead and studied my sweat, too. Clear. I was somewhat surprised. I half expected it to be black. Maybe with a little mold.

Emmaline studied my sweat on her tiny little finger as if it might hold the answer to eliminating menopause. She held it up to the beams of light glancing through the windows, then held it about five inches from her eyes. Next she smelled it.

“I bet that smells yummy,” I told her.

“No, not at all,” she said, her voice accusing. “It smells like fear.”

“Fear?”

“Yes. Fear. Truckloads of it. So, let’s start with that. What are you fearful of?” She wiped my sweat on her pant leg, and fixed those sharp, brown eyes on mine like lasers.

“I’m not afraid of anything,” I told her. I sat up straighter in my beanbag, glad that the rest of my sweat was drying. I am a firm believer that sweat washes away all the bacteria infesting our bodies-the germy yuck that runs through our veins (Rosvita would be proud of my antigerm inner rhetoric), although I would rather not be wearing a silk shirt when punching a bag.

No, I wasn’t afraid of anything, but it’s not what you think. I wasn’t afraid of anything because I didn’t care anymore. Not at all. I was done. I wasn’t sure I cared to live anymore. The analytical part of me knew it was a dangerous place to be.

“Yes, you are.” She whacked the side of the beanbag. “Fear is lacing your life. It’s behind all of your problems. It’s behind your anger. And your impotence.”

At the word impotence, I thought of Slick Dick’s little dickie. He obviously had enough kick in his dick to get it up for his girlfriends-as well as for me. I had heard from my doctor. I had insisted on being tested for every STD under the sun. All tests were negative and I was healthy. Good news, but it did not diminish my need to jab needles into his butt.

“You’re getting angry,” Emmaline told me, spreading her arms out wide. “I’m going to catch your anger for you.”

“Spread your arms out wider, Emmaline. I’ve got a heck of a lot more anger than that. Here it comes, one roll of fury after another,” I said, noting the bitter, mean tone. “Perhaps I’ll send you that tad bit of anger I felt when I realized that my career was pointless.” There was that word again. Pointless. I’m pointless.

“Send it over,” she instructed, arms waving.

“Or maybe you would like the anger I felt when I realized that I have hooked up with one loser after another. Let’s see, there was Devon who talked incessantly about himself and only needed a board with eyes painted on it and inflatable boobs to be happy. There was Carl who wanted sex and nothing else, and when I tried to talk to him about anything he pulled a pillow over his head-and for some reason I felt compelled to stay in that relationship for six months. There was Andy who was in love with his mother and wanted me to mother him and left when I wouldn’t fold his socks a certain way.”

I tilted my head at her. “You get the picture.”

“No, I don’t,” Emmaline said. “There’s more. So much more. Tell me.”

“No. No, that’s it.” I crossed my arms. No more.

“Yes. You’re raging. I want you to heal. Tell me.”

“I’m healed.”

“You’re not, Jeanne. You’re raw. You’re hurting.” She leaned toward me, took both my hands. She lowered her voice. “I’m here to help you. I want your anger. I want you to get rid of it. Keep talking, Jeanne.”

I thought about it. Why the heck not. “I’m so angry. I hate myself.”

“I know that. Kick that hate out, don’t be pathetic, don’t be weak. Kick the burning anger out.”

I don’t know why but I felt the tears form in my eyes again. “Okay, well if you can take real burning anger I think I’ll send you the anger from my mother’s death. She was my only friend and now I don’t have any friends besides my brother who I rarely see because I can’t stand to look in the eyes of his children. Perhaps I’ll send you the fury I felt watching cancer eat her alive. Why couldn’t the cancer have landed in the body of a criminal or a creep? Why her? And why do so many people I know who do nothing but pollute the earth with their venom and hate and perversity get to live and she doesn’t?”

“Keep it coming, Jeanne. All of it. There’s more, I can feel it.”

I tried to pull my hands away, but she wouldn’t let me.

Oh, yeah, there was more and I felt that anger ripping through me like a chain saw, noisy and relentless.

“Well,” I tried to sound nonchalant but my voice caught on a sob. “There was Johnny Stewart. We met when I was in graduate school and he was in medical school. We were twenty-five.” I started to shake. Surely I was over this, almost twelve years later?

“I’m feeling your fear again, Jeanne. This is the worst of it. Your negatives are radiating. Don’t be a wuss here. Get it out.”

“Johnny always liked to sing.” I wiped tears off my face because my cracking heart was making me cry. “We would sing together all the time. He played the guitar; I played the violin. We decided we were going to get married and live in the country and have five kids and a farm.” I wrenched my hands away from Emmaline’s, then got up and slammed both hands into the punching bag, not bothering to wipe my tears. “He was going to be a doctor and I was going to raise the kids. We would go camping in the summer and I would volunteer in their classrooms and take care of the cows and chickens and horses. We would go to church on Sundays and have a bunch of friends. Did I mention the five children? We had even picked out names we liked.”

“Hit it out, Jeanne. Rip it out and let’s deal with it. Be strong enough to deal with it.” She flapped again. “Speak of it. Get it out in the open, out of your heart.”

“It’s never leaving my heart,” I told her, pummeling my hands into the bag. My body shook again, like a leaf would shake if you grabbed it by its stem and held it up in a tropical windstorm.

“Tell me.”

“Well, there was the little matter of my being pregnant. When I was twenty-five, during my last year of graduate school.” I smiled. My smile wobbled. Salty tears flowed into my mouth. “We planned on getting married after we graduated and having kids. But he was so happy that I was pregnant and I was so happy and we both cried. He always put his head on my stomach and talked to the baby.

“Before the ultrasound told us we were having a girl, Johnny would tell the baby he loved her, that her mother loved her. He would talk to the other side of my stomach and tell the baby that he loved him, that his mother loved him.”

I shuddered, smacked both fists into the bag.

“We would name it Grayson if the baby was a boy, after my father, and Ally, after my mother, if the baby was a girl.”

I felt ill. I hadn’t even spoken about this in twelve years. I had only talked about it with my mother who rocked me back and forth, in and out of my hysterics. I felt like it was yesterday and felt the full force of my grief. I could still smell it.

“Tell me, Jeanne.”

“No, I can’t.”

“You can, I’m listening. Let it out.”

Let it out? Let it out so it could eat me alive once again? So it could drive me to my knees? How fun. This counselor knew how to make a client have a good time. “Two weeks after I found out I was pregnant we got married in the church chapel with his family and mine and about fifty friends and professors from school. I wore my mother’s white lace wedding dress and the veil that she wore and her mother before her and her mother before her. And flip-flops. No heels for me. We were so happy together. We always had pancakes on Saturday mornings and Wednesday nights for dinner.”

I remembered those evenings. We were students. We were broke and we bought pancake mix in bulk. We’d smother the pancakes in syrup and butter and eat naked by our fireplace and laugh. Afterward, Johnny would play his guitar, I’d play my violin. Naked.

“Months later a drunk driver decided that it would be best if he sped down the highway and crashed his car into ours head on.”

I heard Emmaline make a strangled sound in her throat. She wrapped her arms around me. “I’ll take the anger, Jeanne,” she yelled. “Give it to me! Give it to me!”

“Johnny lost his head.” When I said this, I heard my own tone. So nonchalant, so casual, so dismissive of the horror, and yet I saw it as if it were yesterday, as if I were up in a tree watching a shameful tragedy unfold. “I tried to help him, but I couldn’t move. My legs were broken in six different places. My stomach felt like it had exploded. Ally died. She died. Our baby died.”

I tried to pull away from Emmaline, but she wouldn’t let me. I finally leaned against her, my body shaking like that leaf, the leaf breaking off, piece by piece, ripped and shredded by that windstorm.

“The drunk got out of his car and managed to call an ambulance before he passed out.”

I could feel the cool of that night around me. Feel the heat of my blood. Of Ally’s blood and mine mixed together, outside of my body not inside where it was supposed to be. I was six months pregnant. I saw Johnny’s headless body in the dark and then everything slipped into oblivion. It was like my mind shut down and I closed my eyes and I shut down and out.

I woke up alive and without Ally in my stomach in the cold sterility of the hospital. I woke up knowing Johnny was long gone. I woke up screaming and had to be sedated. I remember the nurses and my mother holding me, hugging me, loving me in Spanish and in English as I screamed.

Emmaline rocked me, my hands at my side. I thought I would throw up. My eyes moved to the craft corner. Could I not have simply made a craft today? Could I not have simply headed straight to the screaming corner? Could I not have simply died that night?

“Like we planned, she was named Ally after my mother with the middle name of Johnna after Johnny.” My voice cracked and the windstorm met with a tornado and the tornado swept that leaf away and soon that tiny little fragile leaf broke apart piece by piece. Emmaline rocked me back and forth, back and forth as I dropped to the floor and slipped into what would politely be called hysteria. “That’s why I stopped playing my violin. That’s why I didn’t eat pancakes for twelve years. I couldn’t. There were no more pancakes in my life. No more music. None. That was the last time I was me.”

My dry, hacking sobs came up from my soul, ragged and razor sharp. “I miss Johnny. I miss Ally Johnna. God, I miss them. I miss them, I miss them, God, I miss them.”

Before I left Emmaline’s, I slipped into her shower. It was tiny but perfectly clean. First I burned my skin and face with steamy hot water, then I cooled off in freezing cold water. I dried, dressed, cleaned up after myself (I like things tidy) and left the bathroom.

Emmaline was waiting for me. She held up her hands above her head. “Put your fingertips to mine.”

I did so.

“I sense no more anger in you right now, Jeanne, not right now. You must kick the crap out of your anger, your pain. It’s controlled you for too long.”

I bent my head again, and glared at the floor between us.

She put both hands on my stomach, massaged it gently. “You will have more babies, Jeanne, you will.”

She bent onto her heels and wrapped her hands around my knees. “You will heal.”

Frankly, I would be grateful if my healing involved leaving this building and being smashed by a bunch of suicidal pigeons. Dying by suicidal pigeons is not an idle wish. Would I ask the pigeons to dive-bomb me into oblivion? Maybe not, but if they did, I would be okay with that. And that’s a sorry place to be.

“I can’t do it.” No, I could not do it. “I can’t even begin to heal because I would have to think about it. And I can’t. I can’t go through it again.”

“You can,” she told me. She wrapped her fingers around mine, hugged me close and rocked me back and forth, back and forth. “You can. You can. You will.”

I slipped my feet into my heels, left her office, pulled my chin up and, like a drunk homing pigeon, found my way straight to the brewery. To hell with my good intentions of not getting blitzed.

The memories Emmaline had stirred up were raw and crashing down on my head, one after the other. Each horrific moment.

The doctors and nurses had told me at length that I had not sustained any permanent injuries and would be able to have children again, that my bones would heal, the scars would fade. Their earnest reassurances and worried looks meant nothing to me, their voices coming at me as if from disembodied floating heads.

When I still had my legs in slings, dried blood on my face, and an empty, lonely womb, I decided that I would never fall in love with any man again-so in my throbbing, damaged, completely mentally unsound mind, that precluded children. Of course, the screaming would begin again and those same doctors and nurses with the worried looks would sprint over and give me a shot that would put me back to sleep for a little while and out of my misery.

Johnny and I rarely drank alcohol. But two weeks after they died, at my mother’s house, I reached for a glass of wine. Then two. It was the first night I’d slept more than a few hours without waking up screaming, the flashbacks intense, vivid, and terrifying. That was the start of my downward slide. I started drinking more, drinking harder.

My drinking fairly soon got out of my control. My mother and Roy and Charlie all stepped in to help me, but I didn’t want their help. I wanted their love, but not their help. Alcohol fuzzed over my life, and that’s what I really wanted-the fuzziness. I did not want clarity, did not want to work through the past, did not want any more mind-screaming agony.

I wanted the fuzz. And I wanted not to think. So I got a job at an ad agency and I worked. All the time. I was a wunderkind. An unsmiling wunderkind that could somehow put together television ads that brought tears to people’s eyes, laughter to their hearts, and tubloads of money to my bosses.

Two years after the accident my legs and pelvic area didn’t hurt much anymore, probably because I was young and continued running (almost obsessively, I ran) and physical therapy, but my heart felt like it was being pinched by a vise, so I kept drinking.

In fact, I thought to myself in a sudden flash of predrunken clarity, believing I would never let myself fall in love again, hence no pregnancies, might explain the motivation behind my long list of bad men: Choose dickless men, don’t fall in love, use all protections and hence, no pregnancies and no heartbreak.

I headed to the brewery around the corner from Emmaline’s. A young man with a goatee, a big grin, and a hooped earring in his eyebrow helped me pick out a six-pack and a little scotch. He made reservations for me at a nearby bed-and-breakfast when I asked for recommendations. “My mom and dad always stay there when they want to get away from us kids,” he told me, dialing. “Can’t blame ’em. There are nine of us.”

Well, wasn’t that what I needed to hear at that moment? I hated his mother instantly. Nine kids.

Nine.

She had nine and I had nothing.

Gall.

I drove my car up to the bed-and-breakfast, greeted the two friendly male proprietors, one short and one tall, and entered my room. I had a view of Mount Hood. I vaguely thought of calling Rosvita and telling her where I was, but decided I would do it after my beer.

I drank one beer in the soaking tub in my room and a little scotch. I had another beer out on my deck in the dark and a wee bit of scotch. I had one more beer while I watched a movie and a tad more scotch. One more after I sat out on my deck again and cried into my scotch. I passed out in bed, visions of Johnny’s smile and my darling, dead baby dancing through my head.

My mother was there, too. She smiled at me.