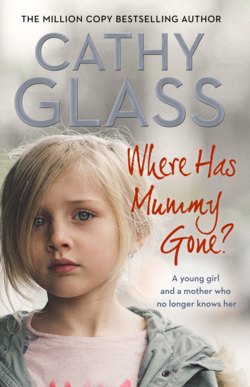

Читать книгу Where Has Mummy Gone?: A young girl and a mother who no longer knows her - Cathy Glass, Cathy Glass - Страница 14

Amanda

ОглавлениеI drove straight from Melody’s school into town, where I bought her a set of casual clothes, underwear, tights, socks, pyjamas, some posters for her bedroom and a pair of school shoes. The shoes size was a guesstimate; I knew the size of her trainers and went up one size. I could change them if necessary. If by Saturday none of Melody’s belongings had arrived from home, I’d take her shopping to choose more clothes, including a warm winter coat – she was wearing one from my spares today. It’s preferable for a child in care to have at least some of their clothes from home, as they are comfortingly familiar, but from what her social worker Neave had said it wasn’t likely, so we couldn’t wait for them indefinitely.

When I arrived home there was a message from Jill on my answerphone asking how Melody had been on her first night. I returned her call and updated her, including that Melody was missing her mother, but had slept well, had eaten a good dinner and breakfast and was now in school. Jill said she’d let Neave know and to phone her if there were any problems. I had a late lunch, filled the washing machine, cleared up the kitchen, which I hadn’t had time to do after breakfast, then Blu-Tacked Melody’s posters to her bedroom wall. Downstairs again, I made a cottage pie for dinner and then it was time to collect Melody from school. I placed a note prominently on the side in the kitchen:

Dear Adrian, Lucy and Paula, hope you’ve had a good day. Would someone please put the cottage pie that is in the fridge in the oven at 5 p.m. at 180°C and keep an eye on it? I should be back from contact at 6 p.m. See you later. Love Mum xx.

I had told them at breakfast I was going to contact, but I was pretty certain no one had been awake enough to hear me.

The bag containing Melody’s shoes was ready in the hall to take with me. She would try them on in the car and, if they fitted, wear them for contact so she looked smart. I liked the children I fostered to look well turned out when they saw their parents, as it was a special occasion, just like when we visited my parents. I then remembered the stay-fresh plastic box containing the rice pudding in the fridge. I hesitated. Melody hadn’t mentioned it again and it seemed rather an odd thing to take to contact, but on the other hand she had wanted to give it to her mother, so I took it with me.

I drove to the school and parked in the same side road I had that morning and then waited in the playground with the other parents and carers for school to end. It was a cold, bright day with the low, wintry sun giving little warmth, but it was a pleasant change from the previous days of overcast grey skies. The bell rang from inside the building, signalling the end of school, and a few minutes later the classes began to file out one at a time, led by their teacher. I looked at the sea of faces – I hadn’t met Melody’s teacher yet so didn’t know who I was looking for. Melody must have spotted me, because suddenly through the milling crowd of children she appeared, coming towards me with her teacher.

‘Hello, I’m Miss Langford, Melody’s class teacher,’ she said with a warm smile.

‘Cathy Glass, Melody’s foster carer.’

‘The Deputy said you’d be here to collect her. So pleased to meet you. Our class’s teaching assistant, Miss May, has been working with Melody today. She’s done some nice work and there is a reading book and some literacy homework in Melody’s book bag. We like the children to read a little every evening. Miss May had to leave early today but is looking forward to meeting you tomorrow.’

‘Thank you.’

Young and fashionably dressed, Miss Langford came across as a very enthusiastic teacher.

‘Please let me know if there is anything I can do to help Melody,’ she said. ‘She’s a lovely child. A delight to teach.’

‘Excellent,’ I said, although I was pretty certain she said this about all the children she taught.

I usually ask to meet privately with the teacher of a new child I’m fostering to learn more about how they are doing in school, but as Melody hadn’t been in school long and I’d had a good chat with the Deputy this morning, I didn’t think I could learn much more.

‘They have swimming on Monday afternoons,’ she added. ‘One-piece swimming costume, please, black or navy, and a regulation white swimming hat.’

‘OK,’ I said. ‘I’ll make sure she has it.’ I made a mental note to buy those too on Saturday.

‘So have a good evening then,’ Miss Langford said. ‘Melody tells me she is seeing her mother.’

‘Yes, that’s right. We’re going there now.’

‘Did you remember the rice pudding?’ Melody now asked.

‘Yes, I did,’ I said, pleased I’d included it. Miss Langford looked at me, puzzled. ‘I made rice pudding yesterday evening,’ I explained. ‘Melody said her mother would like some.’

‘Mmm, that sounds nice,’ she enthused with a big smile and smacking her lips. ‘I love homemade rice pudding.’

‘Well, the next time I make it I’ll bring some in for you too,’ I joked.

She laughed and we said goodbye.

I opened Melody’s car door, gave her the new shoes and then waited on the pavement as she tried them on. They fitted, just. ‘Can’t I have trainers?’ she asked.

‘Not for school, but we can buy you some for casual wear at the weekend.’

‘OK. They’re nice,’ she said. ‘What shall I do with my old trainers?’

‘Put them in the bag your shoes were in for now.’ As worn out as they were, I’d be keeping them, together with the clothes Melody had been wearing when she’d arrived. They were the property of her mother and would be offered back to her. If she told her social worker she didn’t want them then I could dispose of them, but not until then. Sometimes all parents have left of their children are photographs, their old clothes and toys, and faded memories.

I checked Melody’s seatbelt was fastened and gave her the box of rice pudding to hold. Then, with her looking very smart in her new school uniform, shoes and coat from my spares, I began the drive to the Family Centre, chatting to her as we went.

‘How was school?’ I asked. ‘Miss Langford said you’d done some nice work today.’

‘I played with someone in the playground.’

‘Great. You’ll soon make friends.’

‘That’s what Miss May said.’

‘You like Miss May?’

‘Yes. She helps me with my work. There’s me and two boys sit with her and she helps us do what the teacher says. Cathy, why don’t I know as much as the kids on the other tables? You know, the ones that don’t sit with Miss May.’

I glanced at her in the rear-view mirror. Children intuit that they are behind their peers. ‘Because you haven’t been in school much,’ I replied honestly.

‘Is that why kids go to school? So they know lots of stuff and are clever?’ Her question was another indication of just how little schooling she’d had; children of her age usually know why they go to school.

‘Yes, and also to make friends and join in activities.’

‘I guess I should have gone to school more, but my mum needed me at home.’

I didn’t want to demonize her mother, but she had a lot to answer for. ‘Your mum is doing fine, so don’t worry,’ I reassured her. ‘I’m sure you’ll soon catch up with your schoolwork, and I’ll help you at home.’

‘I hope my mum is OK,’ she said, fretting again. ‘I kept thinking about her at school and I told Miss May. She said my mummy was grown up and would know how to look after herself and I shouldn’t worry.’ Thank you, Miss May, I thought.

‘That’s right. I’ll be meeting Miss May tomorrow,’ I said. ‘What else did you do at school?’ But Melody didn’t answer and was clearly worrying about her mother again. ‘We’ll soon be at the Family Centre,’ I told her. There was no reply.

Five minutes later I parked in one of the bays outside the Family Centre and cut the engine. I’d already explained to Melody what to expect: that there were six rooms in the centre, so other children in care would be seeing their parents too, and a lady called a contact supervisor would be in the room with them making notes. The parent(s) often find this more intrusive than the child(ren), for they know why the contact supervisor is there: to observe them with their child and write a report on each session. These reports go to the social worker and ultimately form part of the judge’s decision on whether their child will be allowed home. I sympathize. I think it’s an awful position for a parent to be in, but there is little alternative if contact needs to be supervised. Some contact supervisors handle it better than others and are able to do their job while putting the family at ease.

‘Is Mummy here?’ Melody asked anxiously as I opened her car door to let her out.

‘Hopefully,’ I said. It was exactly four o’clock and parents usually arrived early.

She clambered out, clutching the box of rice pudding, and we went up the path to the security-locked main door where I pressed the buzzer. The closed-circuit television camera overhead allowed anyone in the office to see who was at the door. After a few moments the door clicked open and we went in. I said hello to the receptionist sitting at her computer behind a low security screen on our right. I knew her from previous visits with other children I’d fostered. I gave Melody’s name. ‘Is her mother, Amanda, here yet?’ I asked.

She glanced at her list. ‘No, not yet.’

‘Mummy’s not here!’ Melody cried.

‘I am sure she will be soon,’ I said. ‘I’ll sign us in and then we can sit in the waiting room – there are toys and books in there.’

‘Why isn’t she here?’ Melody lamented as I entered our names in the Visitors’ Book.

‘I don’t know, love. Come on through here.’

‘I bet she got lost. Mum often gets lost when we have to go somewhere new. She needs me to show her.’

‘Your social worker will have told her how to get here,’ I said. ‘Try not to worry.’ The waiting room was empty and we sat on the cushioned bench.

‘What if Mum hasn’t got the money to come here on the bus?’ Melody asked.

‘Neave, your social worker, will have checked she has enough money.’ Parents of children in care are given all the help they need to get to contact, including bus or taxi fares when appropriate.

‘Mum’s not good without me,’ Melody said again.

I thought she was worrying about her mother far more than most children I’d fostered, and I was hoping that when she saw her she would be reassured that she was coping. I was also hoping Amanda wouldn’t be much longer. Her lateness, which was making Melody even more anxious, would be noted by the contact supervisor, who would now be waiting in the allocated room. I knew from experience that we wouldn’t be allowed to wait indefinitely and at some point the manager of the Family Centre would make the decision to cancel the contact and I would return home with Melody. It’s devastating for the child, but not as bad as waiting until the bitter end and having to accept the parent hasn’t come to see them. The child’s feelings of rejection at not being able to live with their parents are compounded and they feel even more unloved. Parents of children in care have to make contact a priority, which I’d have thought was obvious, but isn’t always, especially if the parents are struggling with drink and drug misuse or have mental health issues.

The minutes ticked by. I tried to distract Melody with books and games, but she just sat there clutching the box of rice pudding, listening for any sign of her mother, and asking me every few minutes what time it was. We heard the security buzzer on the main door go a few times, but it wasn’t her mother. Melody wrung her hands and worried something bad had happened to her. Then at 4.30 p.m. the centre’s manager came in and said that they’d tried to phone Amanda but there was no reply, and they’d give her until 4.45 and then they’d cancel it, unless she phoned to say she was on her way. This was more generous than usual and it was because it was the first contact. Usually if a parent doesn’t phone to say they’ve been delayed then only thirty minutes are allowed.

‘Where’s my mum got to?’ Melody asked me again after the manger had left. ‘Something really, really bad must have happened to her, I know. She needs me, it’s my fault.’ Her bottom lip trembled and her eyes filled.

‘It’s not your fault, love,’ I said, putting my arm around her shoulders. I wondered if Amanda had any idea of the pain she was causing her child.

Five minutes later we heard the security buzzer sound again and the main door open and close, followed by a thick, chesty cough.

‘That’s my mum!’ Melody cried, jumping up from her seat. ‘She’s here. Mummy!’ She ran out of the waiting room. I quickly followed her down the short corridor and into reception, where a woman I assumed to be Amanda was giving her name to the receptionist. ‘Mummy! Mummy!’ Melody cried and rushed to her.

Amanda turned and for a second seemed to look confused, as if she wasn’t sure where she was and who was calling her, then, recognizing her daughter, she opened her arms to receive her.

‘Mummy, where’ve you been? You’re late. I was going to have to go home without seeing you!’ Melody cried.

‘Over my dead body!’ Amanda snapped in a threatening tone.

Deathly pale, with a heavily lined face and sunken cheeks, Amanda was stick thin and her jeans and jumper hung on her skeletal frame. Her hair was falling out and her scalp was visible in round bald patches. She looked haggard and aged well beyond her forty-two years. If ever there was an advertisement to deter people from drink and drug abuse, it was her. I’d seen it before in the parents of children I’d fostered and would sadly see it again. She lisped as she spoke and as I went closer I saw her two front teeth were missing.

‘Hello Amanda, I’m Cathy, Melody’s foster carer,’ I said positively. ‘Pleased to meet you.’

She’d let go of her daughter and was now trying to understand what the receptionist was telling her, which was to sign the Visitors’ Book.

‘The Visitors’ Book is here,’ I said, trying to be helpful and pointing to it.

‘Come on, Mummy, you have to write your name,’ Melody said. Taking her hand, she led her mother to the book and then gave her the pen beside it to sign. I exchanged a glance with the receptionist, who was looking at her, concerned. Amanda wouldn’t be the first parent to arrive at contact under the influence of drink or drugs, although I couldn’t smell alcohol and she seemed confused rather than high or drunk. I watched as she made an illegible scrawl in the book, then, setting down the pen, she turned to her daughter.

‘Where do we go?’ she asked her.

‘You’re in Yellow Room,’ the receptionist said. ‘The manager is coming now to show you.’ It’s usual on the parent’s first visit for the manager to show the parent and child around so they know where the toilets, kitchen and rooms are. Six rooms lead off a central play area where the larger toys are kept, and each room takes its name from the colour it is painted.

‘How are you?’ I asked Amanda, trying to strike up conversation. It’s important for the child so see their carer and parent(s) getting along. Amanda looked at me, puzzled, as if she’d forgotten who I was, and I was about to remind her when the manager appeared. It was now time for me to go, as contact had started and this was Amanda’s time with her daughter.

‘When will contact end?’ I asked the manager, as we were starting late

‘Five forty-five,’ she said.

‘See you later then,’ I said to Amanda and Melody. There was no reply. I signed out, and as I left they were following the manager down the corridor and into the hub of the building.

It was dark outside now in winter, and cold. I pulled my coat closer around me and returned to my car. I usually try to put the time when a child is with their parent(s) to good use, either by doing some essential grocery shopping or by catching up on some paperwork in a local café, but now I sat in the car thinking about Amanda. I was starting to see why Melody was so worried about her. She appeared incredibly fragile and vulnerable and clearly needed Melody’s help – as she’d been telling me. The social services had been aware of the family for a while and support had been put in, so I assumed Neave knew of Amanda’s dependency on Melody. But now, having met Amanda, I wondered how the two of them had coped at all. Far from fearing Amanda at that point, I felt sorry for her. No one starts their life wanting to make a complete mess of it and lose their children and die prematurely, which surely must be Amanda’s fate.