Читать книгу The Barefoot Child - Cathy Sharp, Cathy Sharp - Страница 5

CHAPTER 1

ОглавлениеIt was bitterly cold that February morning in the year of Our Lord 1882 and the girl shivered as she shopped in the market, looking for the best bargains to take home for her mother. She’d been given two shillings and for that she must buy a nourishing meal for them all; a meal that would last for several days. Ma had asked Lucy to bring a piece of best mutton and vegetables so that she could make a stew that would be recooked for at least three or four days, ending up as little more than a thin soup, but it was all they could afford.

‘Josh hates mutton stew,’ Lucy had protested. ‘We have it all the time and he says it makes him feel sick.’

‘Please don’t argue with me,’ Lucy’s mother said. ‘My head aches so and I must bake the bread. If you can find another meat as cheap then bring it, but don’t worry me with your brother’s complaints – and Kitty needs new shoes again for her others are falling to pieces.’

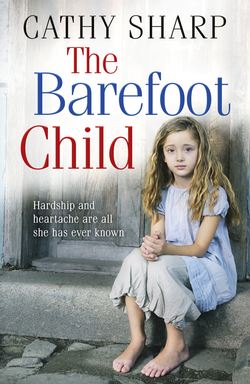

It was true, Kitty’s shoes had holes in the toes to allow for growth and Lucy’s sister had been in tears over it the previous day. She’d told her that she must wear them a little longer or go barefooted. Kitty had flounced off to bed, saying she would rather go barefoot than wear them. As usual, these days, Lucy’s mother had blamed her for her sister’s lack of shoes. Lucy knew it was hard for Ma now that Pa was lost, together with all the money he’d invested in his cargo. Life had never been easy but since he was lost, Ma had become bitter and harsh.

Lucy blinked away the foolish tears. She was fifteen, her sixteenth birthday looming in early March, and the burden of looking after her brother and sister had fallen on her shoulders since Ma’s illness the previous winter.

Lucy didn’t mind scrubbing the kitchen floor for her mother before she left for work in the nail factory, nor did she mind preparing her siblings’ tea at night, though she was often so tired she could barely stand. She didn’t even mind that she had to go shopping on her afternoon off, but it hurt that Ma was always sharp with her, always complaining that she was lazy and that she neglected Kitty and Josh when it wasn’t true.

It had never been like this when Pa was alive. Lucy blinked rapidly to keep her tears away. Pa was a big, golden-haired man who seemed to fill the room with his booming voice when he was home from the sea, but he was dead, lost to them all. The sea he’d made his living from had swallowed him up in a big storm and for months they’d known nothing, but then the news had arrived of Storm Diver’s sinking and Lucy had wept bitter tears into her pillow night after night – and her mother had changed from a happy and loving wife to a bitter woman who never smiled.

‘Dreamin’ again?’ Lucy’s thoughts were hastily ended as she found herself confronted by one of the barrow boys who plied their trade in the busy market at the heart of Spitalfields. ‘Dreamin’ of me, I’ll swear – of the day I put me ring on yer finger …’ He was always teasing her, always pretending that he was going to marry her.

Lucy’s cheeks fired as her gaze avoided Eric Boyser’s wicked grin. A thin lanky lad, he wore a rusty black jacket, a threadbare cap, and baggy trousers he kept up with a piece of parcel string. Eric’s jacket was patched and patched again by his widowed mother for whom he worked. Mrs Boyser owned the stalls Eric ran and paid him only a few coins a week – and she didn’t like Lucy’s mother so there was no possibility that she would allow a marriage even if Lucy wanted it, which she didn’t. She was much too young for such things and if she did ever marry she wanted a man like her golden father – not a thin, dark, gangly boy with a long nose who thought it was funny to tease her.

‘I’m not dreamin’ I’m thinkin’,’ Lucy defended herself. ‘I need something to make a good meal that can be reheated for three days – but not mutton. Josh does hate mutton so …’

‘Don’t blame him. I don’t like it much either,’ Eric said. ‘Why not make chicken and vegetable pot in the oven? You can add everythin’ same as a mutton stew and it lasts as long – unless yer eat it all quick ’cos it’s too delicious!’

‘I haven’t got much money,’ Lucy whispered, ashamed. ‘I don’t earn much at the factory and Josh gets less than I do – and Ma’s not been well enough to work since last winter when she had that terrible chill.’

‘Show me,’ Eric demanded and she opened her hand to show him the pennies and sixpences. ‘Two shillings – that’s enough. Todd will have some leftover chicken joints by now and I’ve plenty of veg you can have cheap, lass.’

Lucy curled her fingers over the money. ‘I don’t want charity …’

‘Nay, Lucy, don’t get miffed.’ Eric grinned. ‘Todd alus grumbles as folk don’t want the back and leg joints. He sells the breasts and has to take all the leftover bits for his missus – and his missus Sal won’t use ’em; she wants whole ones to roast so he gives the bits to the stray dogs. He’ll sell you a good big parcel for a bob and you can have sixpence worth of veg from me – last you most of the week, that will.’

Lucy hesitated, nodding shyly, forcing herself not to let pride get in her way. ‘Thank you,’ she said. ‘Chicken would be a lovely change for Josh and Kitty.’

‘I’d do anythin’ fer yer.’ Eric gave her a look that made the colour rush up her pale neck and into her cheeks. ‘Nay, I never wanted to upset yer, lass – but I like yer, see, and one day … well …’ He left the rest unsaid and Lucy warmed to him.

‘Show me where to go,’ she said. ‘I’ll buy the chicken I can afford and come back for the veg.’

‘I’ll come wiv yer, ’cos Todd can be a surly bugger, but he likes me!’ He signalled to one of the other barrow boys to keep an eye on his stall and joined her.

‘Thank you,’ Lucy said, because she hated asking stallholders for their bargains. Some of them just told her to clear off, others made her uncomfortable by hinting that they’d be more than willing to help her if she obliged them – and, understanding what they meant, Lucy always backed away, shaking her head.

She was innocent; and yet, brought up in the rough streets that surrounded the East India Docks, she could not be unaware of the realities of life, of the whores who paraded up and down outside the taverns on a Friday and Saturday night, flaunting their almost naked breasts, hoping to relieve the men of a few shillings from their pay before it all went on drink.

Lucy was a pretty, delicate girl with a pale complexion and fair hair, her eyes more green than blue, and in the summer she got little brown freckles over her nose and cheeks, which she hated. She’d been propositioned more than once when fetching two pennyworth of gin for her mother’s cough of an evening. Mary Soames knew well enough that the gin did nothing for her cough, but it relieved her misery a little and Lucy never refused to do her mother’s bidding, though had Pa been home he would not have approved.

Now, she walked beside Eric to the stall where the big, red-faced butcher was busily chopping up a chicken for a customer. Very few of the women who bought from him could ever afford to buy a whole one for roasting. However, the large boiling fowls that made up the biggest part of his stock were always available and Todd obliged his customers by dividing them into segments. Eric hadn’t quite told Lucy the truth when he said Todd had to take the worst cuts home at the end of the day, because there was always someone willing to pay a few coppers for a parcel of bits and pieces.

‘What do yer want then, little toad?’ Todd asked Eric but the insult was more a caress, because the two were good friends.

‘My friend Lucy wants chicken she can make into pot meals for her family,’ Eric said and gave him a wink. ‘What ’ave yer got fer a bob?’

Todd stared at Lucy for a long moment and then nodded. ‘I’ve got half a dozen backbones ’ere, lass, three thighs, four drumsticks and half a dozen wings. My missus won’t use ’em and I’ll be packin’ up in ten minutes. I reckon yer can ’ave the lot.’

‘Thank you!’ Lucy smiled. ‘Are you sure I can have all that for one shillin’?’

‘Aye, lass, yer can,’ the butcher said. ‘There be some giblets an’ all; they make good tasty gravy or soup and I’ll chuck them in fer nothin’.’

Lucy wondered at his generosity, but the offer was so tempting that she couldn’t refuse, because with the shilling left to her she could buy a small heel of cheese, eggs as well as veg from Eric. Josh did so love cheese, though it was a treat he didn’t often get.

‘You’re very kind, sir,’ she said but the big man shook his head.

‘I reckon you be Matthew Soames’ girl,’ he told her. ‘I remembers him – a good man what did me more than one favour. You come to me every week you fancy chicken and I’ll save me bits fer yer.’

Lucy thanked him, took her parcel wrapped in newspaper, and walked away with Eric, who’d left his stall to the care of one of the other barrow boys. Neither of them noticed the man staring at her from across the road, a gentleman, by his appearance, but with a sour, angry expression that made him look ugly. Lucy paused to buy a small segment of cheese and four eggs from the stall next to Eric’s and by the time she turned back to him, he had a large packet of veg ready for her. He took her sixpence and grinned.

‘I hope Josh enjoys his dinner,’ Eric said. ‘I’m always ’ere, Lucy, lass. If yer ever need ’elp, you come to me.’ The look in his eyes made her blush, but she knew he meant no harm.

Lucy turned for home, her large rush basket heavy over her arm. She had a long walk ahead and it was bitterly cold, but there was a warm glow inside her as she thought of what she could make with her purchases. In her hurry to get home, she did not notice that she was followed. One of her neighbours met her and walked the rest of the way with her. Neither saw the scowling face of the man who turned away, thwarted of his prey.

‘Where did you get all this lot?’ Lucy mother asked as she unpacked her basket, revealing the onions, a stick of aromatic celery, carrots, parsnips, a turnip, a large winter cabbage and three oranges that were in Eric’s parcel. ‘I told you to spend no more than two shillin’s. I need the rest of your wages for the rent or the landlord will put us out on the street.’

‘I spent what you told me,’ Lucy replied, flinching as she received a slap on her ear. She pressed a hand to her ear, looking at Mary indignantly. ‘What was that for, Ma?’

‘You’re lyin’ to me or you’ve been doin’ somethin’ you shouldn’t,’ her mother said harshly. Her thin face was pale and her mouth was pursed in a bitter line. ‘I’ve told you not to ask for charity.’

‘I didn’t!’ Lucy protested, though she knew the butcher had been generous, partly because of her father and partly because Eric had told him she was his friend. ‘The butcher couldn’t sell these bits and he was packin’ up; they wouldn’t keep until Monday.’

‘I’m ill, not a fool,’ her mother said. ‘There’s plenty would buy these leg joints from him – but if he was packin’ up mebbe …’ She frowned. ‘That still doesn’t explain all these veg – and them oranges! It must have cost a shillin’ at least.’

Lucy knew Eric had been too generous, but he liked her and he’d wanted to show it; however, she couldn’t tell her mother that, because she would immediately think that Lucy had let him touch her. Lucy knew it happened. She’d seen it often enough, a giggling girl and her chap in the shadows, and her mother was bound to think the worst, because she’d lectured Lucy about the dangers of letting men touch her, from the day she was ten.

‘I swear I didn’t do anything you wouldn’t like.’ Lucy crossed her fingers behind her back. ‘I swear it on Pa’s memory.’

Her mother’s eyes snapped at her angrily but she said nothing, just turned to take the bread she’d baked from the cupboard in the corner. It was a handsome mahogany piece and Lucy had noticed their neighbour look covetously at it when he’d first seen it. Lucy’s father had brought it home from one of his voyages abroad and she thought it must be worth a few pounds, but Ma would never sell it. They managed to pay the rent for their cottage and live on the money that she and Josh earned, though it was little enough, and none of them had had new clothes or shoes since Pa was lost.

‘You can start on the casserole,’ Mary Soames said, intimating that the discussion was over. ‘We’ll all have a piece of bread toasted with cheese when Josh gets back. It’s a treat and I haven’t tasted cheese in months!’

Lucy turned away with a sigh. She’d hoped to make Josh cheese and pickles in bread for three days out of that cheese, and now it would be gone in one go. It wasn’t fair, because Josh had to work so hard and he brought every penny home. He didn’t like the penny dripping that Lucy bought from the butcher in Commercial Road, so often took just bread for his midday meal. Most men and boys spent at least half their wages on themselves, often on drink. Josh wasn’t old enough to go drinking after work and that cheese was meant to be his treat, but Lucy couldn’t defy her mother. Tears stung her eyes; she understood her mother was ill, but she longed for a warm smile or a loving touch.

‘I won’t wear them anymore,’ Kitty cried throwing the offending shoes at her sister later that evening. ‘They make blisters on my heels and they let water in!’

Lucy saw the shoes were beyond repair. ‘I can’t afford to buy you a pair this week, Kitty,’ she said. ‘Will you not wear them until I have saved enough?’

‘Why should I?’ Kitty demanded, her mouth wobbling. ‘Pa would never have let me wear them knowing they hurt my feet.’

Lucy knew her father would have sold something of his own to buy new shoes for his daughter. Lucy wracked her brain, but there was nothing she owned of any value. There was nothing she could do but sell her Sunday shoes to buy her sister a decent pair of boots. It would leave Lucy with just her working boots, which were stout and well-protected, with iron studs in the soles and heels, but she had saved her pennies for months to buy her Sunday shoes – yet she had no alternative for her mother said it was up to her as the wage earner to provide shoes for Kitty.

Lucy took her shoes to the market in the fifteen minutes she was given for her lunch break the next day. She looked at the shoes on offer and saw a pair in red leather that were just Kitty’s size and red was Kitty’s favourite colour.

‘How much for those?’ she asked, pointing to the red shoes.

‘They’re fine shoes for a young lass,’ the man said eyeing her eagerly. ‘Hardly worn, they be, miss – and cheap at seven shillings the pair.’

Lucy held her breath because it was so much money and she wasn’t sure he would give her as much for her own shoes. Yet perhaps he would hold them for her and Lucy could pay a few pennies a week until she had enough.

Taking her own Sunday shoes from under her shawl, she showed them to the stallholder. ‘What will you give me for these?’ she asked. She had bought them six months earlier for five shillings from another stall and had had them repaired once.

‘Three and sixpence,’ the man said. ‘It’s a fair price. I doubt you’ll get more.’

‘I wanted to exchange them for the red ones – for my sister …’

He laughed mockingly. ‘Think I’m a fool do yer – clear orf and don’t bother me until you can pay!’

Lucy turned away, feeling the despair wash over her. Why did life have to be so hard?

‘Wait up!’ the man called after her and Lucy hesitated, turning back in dread for she feared what he might say. ‘I’ll take them shoes and the boots on yer feet – and you can have the shoes for another sixpence …’

About to shake her head, Lucy remembered that there was a spare pair of her father’s working boots in the cupboard under the stairs. They would be miles too big for her, but she could stuff the toes with newspaper and they would do. She would not be the only girl at the factory to wear her father’s old boots.

She bent down and unlaced her boots, handed them, her best shoes and the last sixpence from her purse, and took the red shoes, wrapping them in her shawl as she walked away. The cobbles were hard beneath her feet and small stones pricked at her, making her wince. She began to run home, knowing that she must find her father’s boots before she could return to work, because it would be too dangerous on the floor of the nail factory with bare feet.

‘Oh Lucy!’ Kitty swooped on her and kissed her when Lucy returned from work that night. ‘My shoes are lovely. They fit me perfectly, with a little room to grow in the toes.’

‘Good, I’m glad.’ Lucy sat down wearily. Her own feet hurt, because her toes had pressed against the newspaper all day and it was harder to work in the heavy boots that had once been her father’s. They were stout and protected Lucy’s feet from the discarded and broken metal on the floor of the nail factory, but the paper chaffed and her big toe was bloody under the nail. She would need to wear a pair of Pa’s old socks over her own in future to protect her feet.

‘Lucy, what’s for supper?’ her brother asked. ‘I’m hungry.’

‘It’s on the stove,’ Lucy’s mother said and looked at Lucy’s feet, shaking her head. ‘Where did you get those, Lucy?’

‘They were under the stairs,’ Lucy told her and wriggled her toes as she took them off. She would rather be barefooted than wear them except when she had to and as soon as she could she would buy some boots that fit her properly, but it would take her months to save for them.

‘Lucy – did you sell your boots to buy my shoes?’ Kitty’s eyes widened in surprise and she looked a little ashamed.

‘And my Sunday shoes,’ Lucy said. ‘Make sure you take care of those, for it will be a long time before I can buy new again …’

‘Oh, Lucy,’ her mother said and shook her head, ‘why did you not ask me? I have a spare pair of boots in my cupboard. You might have sold those instead.’

Lucy said nothing for she knew that had she asked her mother would have refused. ‘Pa’s old boots will do for work,’ she said. ‘I shall save up until I can buy some new ones.’

‘Well, I think you are very foolish,’ her mother said. ‘Return to the stall tomorrow and see if he will change your boots for your father’s.’

Lucy nodded, acknowledging the sense of her mother’s words. She would pop back to the stall in her lunch break again and ask if he would exchange them for her.

Lucy stared at the stallholder in dismay. He had sold her working boots almost as soon as she’d left the stall the previous day, he said.

‘I’d buy those boots,’ he told her pointing to her father’s boots. ‘I’ll give you five shillings for them – if there’s anythin’ on the stall you want.’

Lucy looked but there was nothing to fit her save her Sunday best shoes, which were now priced at seven shillings and beyond her.

‘I’ll leave it for now, thank you,’ she said, ‘but when I’ve saved a bit I’ll come back and exchange my boots for something that fits me better.’

Turning away in disappointment, Lucy knew her boots hardly showed beneath her long skirts, but they felt uncomfortable and she would rather be barefooted, but if she injured herself at the factory her family would starve. For the moment she would just have to put up with the discomfort and take them off when she got home.

‘Here, have these instead,’ Lucy’s mother said, handing Lucy a pair of her own boots; they were scuffed and worn but almost fitted Lucy. ‘They are still too big for you but better than your father’s old boots.’

‘The stallholder said he would give me five shillings for Pa’s boots,’ Lucy said and saw her mother’s eyes light up.

‘Then wear mine, sell your father’s boots – and give me the money.’

Lucy hesitated. Her mother’s boots were almost worn through at the soles, but if she stuffed layers of paper into them they would last for a while and fit better. If she could keep the money for Pa’s boots she could have them repaired – but she could not refuse to give her mother the five shillings.

‘Thank you,’ she said. ‘That was a kind thought, Ma.’

‘You shame me going about in a man’s boots,’ her mother said harshly. ‘Besides, I could do with that five shillings …’

Lucy turned away biting her lip. She’d thought her mother’s concern was for her but it was merely for appearances.