Читать книгу The Boy with the Latch Key - Cathy Sharp, Cathy Sharp - Страница 6

CHAPTER 2

Оглавление‘Angela, how lovely to see you,’ Sister Beatrice said, welcoming the woman who had been their Administrator at St Saviour’s for several years, and whom she sadly missed. ‘It seems ages since you visited us …’

‘Not for want of trying,’ Angela Adderbury said and smiled. ‘The twins had whooping cough last month, and then I had to pop down and see my father. I told you he hadn’t been well, didn’t I?’ Sister Beatrice nodded. ‘He had a few days in the nursing home and seems much better – and the lady he intends to marry had just taken him in a lovely bowl of fruit.’

‘Your father is getting married again?’

‘Yes, at last. He and Margaret have been friends for years. After my mother divorced him, he waited for a while before asking her, but I think his illness made his mind up for him. It’s happening next month …’

‘Spring is a lovely time for weddings,’ Sister Beatrice said. ‘Are the twins quite well now?’

‘Yes, and into everything,’ Angela said. ‘One day I’m going to get time to organise some more fundraising events for you, but at the moment my hands are full. Mark is always offering to help, but although he plays with them in the garden, he’s not good when they’re screaming and acting up. He lectures them about proper behaviour when all they need is a smack on the bottom and they behave. His intentions are good, but he isn’t really into childcare.’

‘Mark is a busy man, and children need a lot of patience,’ Sister Beatrice said. ‘I do miss your exciting projects, Angela, but I know Mark and your sons must come first.’

‘Things have changed a great deal since we worked together, Sister.’

‘Yes, and I’m not convinced they are entirely for the better. I’m sure the government’s intentions were good when they brought us all under the state umbrella, but an institution is only as good as those that run it.’ She paused for thought, and then, ‘It sometimes seems to me that all they’ve given us is miles of red tape. Naturally, we must abide by the government’s new rules, but St Saviour’s was always run with the same principles of love and care as the law provides. We have never given our children cold showers or sent them to bed hungry night after night, or treated them as if they were prisoners in a place of correction. I know that in the past many orphanages did these things, but I should never have been a party to such practices …’

‘Nor I,’ Angela agreed, ‘but St Saviour’s was always the gold-standard and the government needed to protect children from the harsh acts of those less caring than you and your staff, Sister Beatrice.’

‘Perhaps they ought to remember that when they descend on us for an inspection with scarcely an hour’s warning. So far we’ve had nothing but praise for our care, though they criticise the state of the toilets sometimes, because we’ve had a leak no one seems to be able to fix. They warned us last time that water on cloakroom floors can make them slippery. As if we needed to be told! I have no patience with all this mealy-mouthed nonsense!’

Her disapproval when speaking of the state supervision was obvious, but since the Children’s Act some years earlier the Children’s Department was taking over more and more and dictated a great many rules and regulations, against which Sister Beatrice had railed bitterly for some time. She, like everyone else, had grown used to the fact that they had to defer to the Children’s Department, who had taken over the new wing for their own purposes, and although Sister Beatrice was given a free hand with the day-to-day running she now had to report anything of importance to the Superintendent next door – a young, and in her oft-spoken opinion, pert woman who was far too inexperienced for the post.

‘Well, I’ll find time to organise a dance this summer, I promise – and one day soon the twins will be back at school. Mark says he doesn’t mind looking after them sometimes, but he’s so busy and … actually, I find I enjoy looking after them myself. I suppose we could employ someone to help but just for a while I want to be a full-time mother and wife. I have left them with a friend today; Janni is fond of them and always enjoys having them for a few hours, but I’ll go back on the evening train, because I hate leaving them for too long.’

‘I think you’re entirely right,’ Sister Beatrice said. ‘Nothing is more important in my opinion. Have you seen Nan at all?’

‘Not since her wedding to Eddie I’m ashamed to say,’ Angela admitted. ‘I sent her a birthday card and we always exchange Christmas cards, but I must try and see her while I’m in town for a couple of days.’

‘I know she would be delighted to see you,’ Sister Beatrice said. ‘Nan visits me every week, to have a chat and a cup of tea. I’m partial to her cakes and she is very good to me.’

‘You’ve been friends for such a long time,’ Angela said. ‘You must miss her terribly?’

‘I was always confident that St Saviour’s was in good hands when Nan and you were here,’ Beatrice confided. ‘I still have good people here but it isn’t the same next door – especially in certain regards …’

‘Do you have trouble from the girls?’ Angela frowned, because it had caused great controversy when the Children’s Welfare Department had taken over part of St Saviour’s for their disturbed girls. Beatrice herself had resisted the change, but the Board had been told it was necessary to use all facilities to the full and forced to agree.

‘I was against it from the start,’ Beatrice said, looking over the gold-rimmed glasses she’d recently started to wear more often. ‘I cannot say that I like this new woman they’ve put in charge either. Her predecessor seemed a sensible woman but this girl is too full of herself …’

‘She respects you, doesn’t she?’ Angela looked con-cerned. ‘You are in charge here, Sister Beatrice. Miss Saunders runs her department but in day-to-day matters, you are still responsible for our children. Although under the supervision of the state, we are still an independently run charity. Of course as an employee of the Children’s Welfare Department Miss Saunders does have the authority to override us if she thinks we’re doing something wrong …’

‘She would like to take charge of the whole place if she could,’ Beatrice sniffed. ‘She is a very modern young woman, Angela. Not your sort at all, brash and abrasive in my opinion. She may keep good discipline with her girls, and I dare say they need it – but I do not care for all the things she says. She came from a working-class background, as I did myself – but I never was radical in my ideas. Compassion mixed with sense, and morality, is my motto, as you know.’

‘Yes, I do,’ Angela agreed and Beatrice laughed as she recalled their disagreement over using the cane on children. Angela had been totally against it and Beatrice had come round to her way of thinking.

‘You taught me a lot, my dear, and perhaps I shall learn from Ruby Saunders, but at this moment I do not think it.’

Angela drank her tea and looked thoughtful. ‘If you are really uneasy about her I could have a word with Mark? The Board has some influence with the Welfare Department. It is still early days for them in all honesty. It would be impossible for them to take over every orphanage in the country and run them. They are overwhelmed by sheer numbers and rely on private institutions like ours and Barnardo’s to take some of the strain … and therefore open to a little gentle persuasion now and then.’

‘Say nothing at this stage; Miss Saunders has only been in the job a few weeks and I don’t want to undermine her position. I dare say we shall get used to one another in time.’

‘I’m sure you will,’ Angela agreed. ‘I bumped into Wendy on my way up. She seems happy here?’

‘Yes, she is my only staff nurse at present and a good one. I thought she might marry but when Andre died she seemed to accept that her life was here and, although she has friends, I do not think she will marry.’ Beatrice paused. ‘You must see Muriel while you’re here, Angela. She is always asking after you. I fear she may retire after Christmas so you should take the opportunity to see her.’

‘You’ll be sorry to lose her, and the children enjoy her cooking,’ Angela said. ‘You’ve kept several of the staff, haven’t you? Once upon a time we were always having them leave us, but Tilly and Kelly are still here, although I understand Tilly got married last year and works just three days a week?’

‘Yes, but that is sufficient most of the time. Nurse Michelle still does a shift two mornings a week, and Nurse Paula comes in as relief when Wendy has her holiday. I’m trying to secure the services of another nurse full-time, but it isn’t easy. You did know that Wendy’s friend in France died of his war wounds in 1950?’

‘It was just about five years ago, before I left to have the twins, so yes, I did know,’ Angela said. ‘I think she lost two men to the war and is now a dedicated career nurse.’

‘Wendy is my rock,’ Beatrice confirmed. ‘She takes a month’s holiday in France once a year to visit the May twins and her friends there, but the rest of her time is devoted to St Saviour’s so we are very lucky.’

‘Extremely,’ Angela agreed. ‘Well, I think I’ve taken up enough of your time, Sister Beatrice. I’ll go and see Muriel and then I’m meeting Mark for lunch.’

‘Give him my best regards,’ Beatrice said.

She took her glasses off and rubbed the bridge of her nose as Angela went out. It was good to talk with old friends and she didn’t see enough of either Angela or Mark, because they lived in the country and were more closely involved with Halfpenny House, which was nearer for Angela to pop in when she had an hour to spare.

Glancing at the paperwork in front of her, Beatrice sighed. Reports had never been her strong point and Angela had helped her so much with that kind of thing, but life moved on and the years seemed to fly by. However, she had a part-time secretary who came in once a week to keep the accounts straight. She was efficient, and would type up the report that Beatrice had written out, but she just wasn’t Angela. Oh, well, there was no point in trying to hold on to the past.

‘Sister Beatrice, may I have a word?’ Sergeant Sallis tapped the door as he put his head round. ‘I just passed Mrs Adderbury on the stairs. She said she thought you might have time to speak to me?’

‘Certainly,’ Beatrice said. She’d known him from the time he’d first joined the force and he was still as helpful and polite as he’d been as a constable. ‘What can I do for you, Sergeant?’

‘More of the usual,’ he said ruefully. ‘A couple of children in trouble, I’m afraid. The mother is in our cells awaiting trial for embezzling from her firm. She seems a decent woman and I can’t believe she did it, but the evidence is damning and that means the kids are on their own. I spoke to the Children’s Department and they advised bringing them here until something can be sorted out, otherwise they’ll have to leave London. All their resources are stretched to the limit …’

‘You want to know if we have a place for the children?’

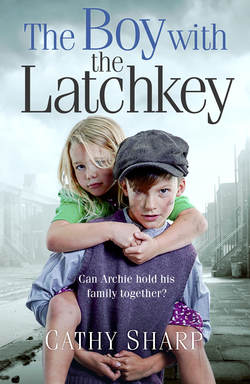

‘Yes, I’m afraid I do,’ he said regretfully. ‘I know you’re full to bursting – but the boy is rebellious and if we don’t keep them together I think he will get into serious mischief. He went round to the factory where his mother worked in the office and when they told him she’d been arrested he lost his temper. Threw things about and yelled at the manager – called him a liar. Mind you, I don’t like that Reg Prentice myself.’

‘Oh dear, the rebellious ones usually end up next door, at least, if they’re girls.’

‘Archie is a decent lad. His neighbours all say he’s done his best to help his mother since his father died, but she was having a hard time of it … They live in a row of slum houses that are hardly fit for habitation, but she kept hers like a new pin inside.’

‘Do you think she took the money out of desperation?’

‘I’ve spoken to her and I believe she’s innocent, but she’s been committed for trial. The evidence seems to prove her guilt, and money has definitely been taken from the firm – stolen cheques as well as cash from the safe …’

‘What will happen to her if she’s convicted?’

‘She is previously of good character and if we can get someone to speak up for her, she might get off lightly – but it depends who is taking the case.’

‘So the children have no home …’

‘Literally,’ Sergeant Sallis agreed. ‘Their house was in any case on the list for demolition and now that the rent hasn’t been paid for a couple of weeks, the landlord intends to board it up ready for the bulldozers.’

‘In that case they must come here,’ Beatrice said. ‘You know we are mostly a halfway house these days. The majority of our children are passed on to Halfpenny House in Essex. The Board think the air is better there for them and I dare say they’re right – though we’ve had two or three run away from the home there. Some London kids just can’t settle anywhere else.’

‘I’m a Londoner myself,’ Sergeant Sallis said and nodded. ‘Right then, I’ll bring them round later. I thought I’d better ask first, because I know you don’t always have room these days. I hoped when they opened that new wing our worries were over, Sister.’

‘Yes, so did I, and for a while we managed well,’ Beatrice agreed with a wry smile. ‘However, the local authority needed somewhere to put their disturbed girls and they decided to take over that wing of St Saviour’s, leaving us to carry on here as best we can. I think they should have taken them elsewhere, but the Children’s Department have the power to do as they want these days.’

‘You don’t get any trouble from them, do you?’

‘From the girls you mean? They can be a bit cheeky, but we haven’t had any real upsets. I think they must be disciplined before they get here. I’m not happy about them being there, because I need the rooms for my orphans, but I was not given an option.’

‘I dare say they thought this side of the home was enough for you to manage …’

‘I may not be a young woman, Sergeant, but I’m not old,’ Beatrice fixed him with a hard stare. ‘I’ve hardly had a day’s illness for years …’ It wasn’t quite true, but she didn’t like it to be thought that she was too old to do her duty. She had no intention of being retired to the convent while she had breath in her body.

‘No, Sister, not at all,’ he said apologetically. ‘I don’t think it would be the same here without you …’

‘Well, I have things to do,’ Beatrice said. ‘Bring the children when you’re ready.’

‘Yes, I shall – and thank you for your help as always …’

Beatrice sighed as the door closed behind him. Her visitors had put her off her stride. She would leave the report for later. It was time for her to check on the sick wards and talk to Wendy about the cases of tummy bug they currently had on their hands.

‘Well, Billy,’ Staff Nurse Wendy said to the tall, well-built young man who had just fixed her medicine trolley for her. ‘You certainly know what you’re doing with machinery. That wheel has been wonky for weeks. Mr Morris said it was past fixing, but it looks sturdy enough now.’

‘I’ve put a steel pin right through and fixed it with a bolt,’ Billy Baggins said and grinned at her. The evidence of his work was spread on the floor, metal shavings, tools and drill, and in his greasy hands, which he was wiping on a much-used cloth. ‘You only have to ask, Nurse, and I’ll see you right. ’Sides, the caretaker has more than enough to do. They make a lot of work next door …’ He jerked his head at the wing used for disturbed girls. ‘He told me he’s had to mend the window at the back three times this month. I reckon they deliberately break the lock so they can get in later at night …’

‘And to think you were the rebel of St Saviour’s,’ Wendy said and smiled at him approvingly, as he cleared the mess and packed his tools away in the battered old bag he kept them in. ‘Always running everywhere and getting into trouble with Sister Beatrice.’

‘Me and her are mates now,’ Billy said cheekily, ‘at least, most of the time. I doubt she’d feel like taking a cane to me now, even if I upset her – and I shan’t do that. She’s all right, she is …’

‘She’s one in a million and don’t you forget it, Billy. No one else would let a great hulking lad like you have the run of the place at your age …’

‘I’m looking for a room I can afford,’ Billy said ruefully. ‘You don’t earn much as an apprentice mechanic, you know. I’m saving up for driving lessons, and to get married as well …’

‘You’re still set on Mary Ellen then?’ Wendy twinkled at him. ‘I remember seeing you at the Christmas party last year … under the mistletoe …’

‘Yeah.’ Billy’s cheeks were slightly pink. ‘We’re promised to each other, but Mary Ellen’s sister won’t let her marry me until I’m doing a proper job – and it will be years before I’m through my apprenticeship.’

‘Well, you’re too young to marry yet, either of you,’ Wendy said. ‘I haven’t seen Mary Ellen for a long time. Is she still working at Parker’s clothing factory in Stepney? I was surprised when she went there; I thought she was set on being a teacher.’

‘Rose made her leave school and be apprenticed in the rag trade,’ Billy said. ‘When she took her to live with her in that posh council flat … Gone up in the world now she’s Sister O’Hanran, has our Rose …’ His eyes flashed with mischief.

‘Well, that is something to be proud of,’ Wendy said. ‘Rose worked very hard, and she always promised that she would have Mary Ellen to live with her when she could afford her own place.’

‘Mary Ellen wanted to stay here with me.’

‘It’s only because Sister Beatrice likes you that you can stay,’ Wendy reminded him. ‘Most of the boys leave at fifteen and you’re eighteen now.’

‘Yeah and I ought to be earning more money,’ Billy grumbled. ‘Well, I’ll get out of your way then …’

Wendy smiled as the good-looking lad left the ward. Billy was like one of her family now. She’d come to the home a year or so after he did and she’d stopped on, just as Billy had. He was a part of the place and helped out with little jobs that needed doing. Mr Morris was the caretaker, but in an ancient building like this there was always something that needed doing: washers on taps, cracked basins, stained ceilings when there was a leak in the bathroom, which Billy had found and fixed without them needing to call in a plumber. Sister Beatrice said Billy was useful, and as he had no family around she’d let him stay on, even though he was working. Wendy suspected the stern nun had a soft spot for the rebellious boy who’d done so well since he joined them at St Saviour’s. He ate sandwiches at work during the day but had his breakfast and supper with the older boys at the home, many of whom still looked up to him. Billy had gained quite a reputation for winning cups for running and football, and he still acted as a monitor at times, keeping some of the wilder ones in order and taking them to football practice in a battered old shooting brake he and a friend borrowed sometimes. Once he’d passed his driving test and could drive without supervision, he hoped to get a small van of his own. It would help with the football team he’d organised for the local youth club, to which most of the lads belonged.

Sister Beatrice had been given the discretion to choose when her children were ready to move on. It was the one clause she’d stipulated when the contracts had been drawn up and the local authority moved in.

‘I must be allowed to decide when my children are sufficiently settled to move on,’ she’d said, fighting tooth and nail for the principles she believed in. ‘Moving a disturbed or vulnerable child out to a place where he or she feels isolated or uneasy can set them back years. While I agree that the fresh air and better facilities at Halfpenny House are so much better for them, their mental state and ability to accept that move is paramount. If everything is to be done in a matter of days I am not the person for the job.’

Mark and Angela had done battle on her behalf, both with the Board of St Saviour’s charity, and the local authorities, who had wanted to impose their own ideas. However, such was the esteem she was held in by the local police, community bigwigs and general population, that her terms were accepted, and even Miss Ruth Sampson, who was still in overall charge of the local Children’s Department, had agreed that they needed Sister Beatrice if the swell of public feeling was to be appeased. Over the years of hardship she’d become firmly entrenched in the hearts and minds of the people of the area and was known as the Angel of ’Alfpenny Street to everyone. Women who slammed their doors in the faces of the council busybodies opened them to Sister Beatrice with a smile and the offer of a cup of tea.

St Saviour’s wasn’t quite the same as it had been in Angela’s time. She’d started up all kinds of schemes to keep the children busy and formed a team spirit amongst the orphans, most of whom had known poverty and tragedy. These days the children were brought here for a while to get over their bereavement and to learn to cope with life again without the parents they’d lost, but then most were moved out to Halfpenny House in Essex, unless they were considered to need a more specialised home. Billy was different. He would never have settled anywhere but the East End of London, and because she knew that, Sister Beatrice had provided him with a home until he could find his own.

Wendy knew how difficult it was to find somewhere decent to live. She’d stayed on in the nurses’ home for a while and taken her time before getting herself a nice little maisonette in one of the renovated buildings within walking distance of St Saviour’s, but she hadn’t done that until after she knew St Saviour’s was going to be her life. At one time she’d hoped that she might marry Andre and live in France, but the shrapnel in his head had moved sharply and entered his brain. Wendy had been horrified when she’d received the telephone call asking her to come at once. It had been too late when she got there. Mercifully, Andre had felt little pain, because it had happened so quickly. Wendy had understood that he’d been badly wounded in the war, but he’d seemed to be well and the shock of his death had devastated her, destroying her last hopes of marriage and a family.

If it hadn’t been for the twins, Sarah and Samantha May, who had some years previously come to them near to starving after their father abandoned them, she wasn’t sure what she would’ve done. Wendy had been instrumental in rescuing them when their uncaring aunt had tried to separate them and she’d accompanied them to their new home in France when their mother’s sister had claimed them, seeing them settled and happy before returning to London. When a couple of years or so later, Andre died and Wendy had wept bitter tears, Sarah had wound loving arms about her and sung her a lullaby in French, and, in remembering all the young girl had suffered, loving her and promising her that she wouldn’t be sad and she would always be her friend, Wendy had found solace.

Eventually, she’d made a nice home for herself above a sweet shop just off Commercial Road, but she knew Billy wouldn’t be able to afford anything like her flat on his wages; it was hard for youngsters with no family to find anywhere decent to live, even though a lot of new building had been going on since the war. If you didn’t dwell on the loss of life, Hitler had done them a favour really, bombing the slums, because there were better homes to be had now; flats and council houses further out in the suburbs. Yet Wendy hated the war and everything to do with it; she’d lost two men she loved to that awful war, and she knew she would never risk her heart again.

She was a nurse and that would be her life, just as it had been Sister Beatrice’s, even though she wasn’t thinking of becoming a nun. Wendy sensed that something terrible had happened to Sister Beatrice when she was a young woman. It wasn’t just that she’d lost a man she loved – no, it was more than that, because it had gone too deep for her ever to recover. Sister never spoke of her past and Wendy wouldn’t dream of asking her. They were friends and relied on one another in their work, but it didn’t go further than that … she couldn’t ask personal details.

Wendy was thoughtful as she started writing up her report for the day. Nurse Paula would be coming to take over in another twenty minutes. Wendy was visiting Nan and Eddie that evening; they’d asked her to supper to celebrate Eddie’s birthday. He was seventy-two and as forgetful as ever, but he and Nan were like family to Wendy. Alice and her husband Bob would be there too; they had three children now and Alice had given up her part-time work as a carer at St Saviour’s. She didn’t need to work now that her husband had a nice little business of his own. He was in partnership with Alice’s cousin Eric, and was married to Michelle, who had worked with Wendy as a nurse when she first arrived. Michelle had one child but had confided to Wendy that she was expecting her second, and so would be leaving, because with two children she wouldn’t be able to manage to work, at least until they started school – and that meant they would be short-staffed again. They had temporary nurses in to cover holidays, and Paula helped out when she could, but they really did need another full-time nurse.

Wendy had just finished her report when Paula came in. She looked cold and was rubbing her hands.

‘The wind is bitter this evening,’ she told Wendy. ‘You want to wrap up well because you’ll feel it when you get out.’

‘It’s supposed to be spring,’ Wendy said and pulled a wry face. ‘Billy came and fixed the trolley for us. He’s very good at it but he wants a better job so he can get married.’

‘He’s far too young to think about it yet,’ Paula said and shook her head. ‘I’m sure Mary Ellen will tell him she’s not ready to marry yet anyway.’

‘Have you seen her recently?’

‘Yes. I met her in the market just this morning. She was on a break from her job at that factory. She’d popped out to do some shopping for her boss. Apparently, he’s a widower and lives alone now that his kids are grown up …’

Paula broke off as they heard a commotion and then someone burst into the ward. The boy was angry and looked as if he’d been fighting the harassed police sergeant who followed him.

‘Get off me,’ the lad said. ‘I ain’t going to let her wash me. I can look after myself.’

‘I’m sorry, Staff Nurse,’ Sergeant Sallis said. ‘Your carer was just trying to tell them they needed to be bathed and looked at and he broke away from her … Come on, Archie lad, let the young lady look after you. She’s only doing her job.’

‘I’ve told you, we can wash ourselves. We’re not dirty and we’ve not got nits or fleas. Mum kept us proper and I’ve made sure June washes every morning and night. If you’d left us alone, we could’ve looked after ourselves at home …’

‘How were you goin’ to do that, lad?’ Sergeant Sallis asked mildly. ‘You’re still at school. You couldn’t earn enough to feed yourselves, let alone pay the rent and the gas. Besides, the landlord wanted you out of the house, because it’s coming down. Sister Beatrice says you can stay here until we sort your mum out …’

‘She didn’t do it,’ Archie said, glaring at him and then at the nurses. ‘Mum ain’t a thief. She’d belt me round the ear if I pinched anything. I know she didn’t do what they say she did …’

‘I believe you, lad,’ Sergeant Sallis said, ‘but there’s evidence that says she did …’

‘It’s false,’ Archie said and looked angry. ‘She told me someone had set her up, made it look as if she was guilty, but I know Mum wouldn’t do anything like that. She just wouldn’t, however hard-up she was …’

‘We’ll get to the bottom of it,’ Sergeant Sallis promised, but looking at his face Wendy could tell he was worried. ‘Do you know anyone who has it in for your mother, lad? Give me a hint and I’ll do what I can, I give you my word.’

‘She didn’t tell me, but I know she was bothered about something,’ Archie said. ‘She wouldn’t let on, because she wouldn’t want to upset us – and we don’t need to be taken into care. Mum will be home soon and she’ll look after us.’

‘Well, until she is, you’re lucky to be brought here,’ Wendy told him. ‘Look, I’ll tell Tilly that you can wash yourselves – but I need to examine you to make sure you don’t have anything infectious, measles or something like that, all right?’

Archie thought for a moment and then inclined his head reluctantly. ‘As long as you don’t start washing our hair with that horrible stuff like the school nurse does to the kids with nits.’

‘I promise,’ Wendy said, smiled at Archie and went out into the hall with him. ‘You don’t need to stop any longer, Sergeant. Archie is going to be sensible now. We have to look after June, don’t we?’ She looked at the truculent lad and saw him nod. ‘At least here you will have decent food and you don’t have to worry about the rent until your mother comes back.’

‘What will happen to all our things? The landlord says we have to get out and they’re going to pull our row down – but I don’t know what to do with our things.’

‘I’ll talk to Sister Beatrice. She’s the Warden here. I can’t promise anything, but someone ought to be responsible. Perhaps we can find storage for you. Sister knows lots of people and she may be able to arrange it.’

Wendy was thinking it was a job for Angela Adderbury. If she’d been here she would have known someone who could store the family’s possessions, but all Wendy could do was ask Sister for advice.

‘All right …’ Archie said grudgingly. ‘But we shan’t be here long. Mum will be home soon and she’ll find us somewhere to live. I know she didn’t take that money and they can’t keep her in jail if she’s innocent, can they?’

Wendy murmured something appropriate, but she knew life wasn’t that simple or that fair. It wouldn’t be the first time an innocent woman, or man, come to that, had been jailed for a crime they didn’t commit. If life turned out the way it should, Wendy would have a husband and children, but she hadn’t and wouldn’t, and she’d had to learn to accept that – as Archie would accept this in time.

She felt for his bewilderment and his hurt, but for the moment there was nothing she could do to help him, except ensure that he was warm, comfortable and safe.

‘Are you hungry?’ she asked.

Archie hesitated and then inclined his head. ‘We had a sandwich at the police station, but that was ages ago.’

‘As soon as you’ve bathed, changed into our clothes and I’ve made sure you’re healthy, which won’t take a minute, because I can see you’re fine, you can have your supper. I’ll ask Cook to make you some eggs on toast – how about that?’

‘I’d rather have beans,’ Archie said. ‘June likes scrambled eggs though.’

‘One beans on toast, one scrambled eggs,’ Wendy said. ‘Tell you what, I’ll make them myself and have my supper with you in the dining room – what do you think?’

‘Yeah, all right,’ Archie said and grinned at her.

Wendy blinked, because the change in him was amazing. This one was a real charmer, she thought and laughed inside, because there was something infectious about that grin. She found herself drawn to the young lad; he’d been like a tiger in defence of his mother’s honesty and she liked that – found it admirable.

Wendy would talk to Nan and Eddie about the family’s possessions that evening, she decided. Eddie was an old soldier and resourceful. He might know somewhere they could store Mrs Miller’s things so that they wouldn’t be looted or destroyed when the demolition people moved in – and if Eddie could help she would oversee the move herself that weekend …