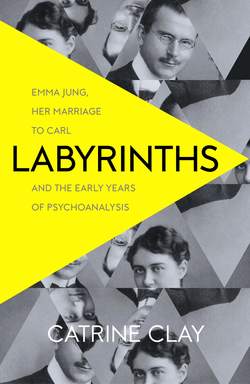

Читать книгу Labyrinths: Emma Jung, Her Marriage to Carl and the Early Years of Psychoanalysis - Catrine Clay, Catrine Clay - Страница 12

A Secret Betrothal

ОглавлениеEmma and Carl were betrothed on 6 October 1901, in secret, at the family’s Ölberg estate in Schaffhausen. The only other guests apart from Emma’s mother and sister were Carl’s mother and sister and the only record of the event are a few out-of-focus snapshots, probably taken by Marguerite, in the garden, where the couple appear to be walking away from the camera as often as towards it, as though trying to avoid it. By the time of the betrothal they had been courting for eighteen months and Emma was nineteen. She looks younger, almost a schoolgirl, and Carl still has the look of the Steam-Roller about him, not yet the confident man of the world he would become. They agreed to wait until Emma was twenty-one before getting married.

Jung had been assistant physician at the Burghölzli asylum for almost a year by then, having moved to Zürich straight after his medical examinations, taking a temporary job in a doctor’s practice to fill in time before starting at the Burghölzli in December 1900. The move puzzled his colleagues and upset his mother. Why would anyone want to leave cosmopolitan Basel for dull, commercial Zürich, and how could he abandon his impoverished mother and sister like that? Part of the reason was that Carl had fallen foul of Herr Professor Wille, the first in a long line of senior men Jung would quarrel with in his working life. Ludwig Wille was the new professor of psychiatry at the University of Basel, the discipline of psychiatry itself dating no further back than the 1880s. In deciding to specialise in it, Jung embarked on the least fashionable and least remunerated branch of the medical profession, seen as another odd decision by his colleagues, given he was one of their best with the brightest of futures. They could not know that psychiatry spoke deeply to the ‘other’ Carl who had had, ever since he could remember, the kind of dreams and visions some people might deem insane. When he read Krafft-Ebing’s 1890 work on ‘diseases of the personality’ in the Lehrbuch der Psychiatrie, he recognised it immediately. ‘My heart suddenly began to pound. I had to stand up and draw a deep breath. My excitement was intense . . . Here was the empirical field common to biological and spiritual facts, which I had everywhere sought and nowhere found.’ Professor Wille, however, was firmly of the old school, seeing all mental illness as the result of a physical deterioration of the brain. Sooner or later Jung was bound to take issue with that, the net result being that he decided to present his doctoral dissertation to the medical faculty of the University of Zürich, not Basel. The city had the added advantage of being closer than Basel to Schaffhausen and Emma.

There were around 400 patients at the Burghölzli asylum when Jung arrived to take up his position, but apart from Bleuler there was only one other qualified doctor, Ludwig von Muralt, the day-to-day care being carried out by unqualified helpers, male and female. This meant an extremely heavy workload for Carl, who also lived on the premises. The only time he had off was Sundays, when he was able to visit Emma, first walking fifteen minutes down the hill to the tram station which in those days did not reach as far as the Burghölzli, then taking the recently electrified tram to Zürich’s Central Station, then the steam train to Schaffhausen, speeding northwards leaving lake and alps behind and into a landscape of farmland, meadows and scattered villages, past the crashing Rhine Falls, finally pulling in to Schaffhausen railway station where he was met by coachman Braun in the green Rauschenbach carriage and conveyed up the hill to the Ölberg estate – thereby travelling from the lowest to the highest niveau of Swiss society all in the course of two hours, a journey which never failed to delight.

And there in the grand front hall waiting expectantly for him was Emma, eager to listen, eager to learn, eager to help. She had started taking Latin lessons in order to read Carl’s medical texts, and maths lessons to discipline her mind, and she was practising her handwriting to help Carl with the daily reports which Bleuler was most particular about, regardless of how many hours it took to write them up. Boring for Carl, but thrilling for Emma. As to her general knowledge: as with Carl, the natural sciences were her enthusiasm; so too her interest in the Legend of the Holy Grail, which had likewise been Carl’s for many years. Emma meant to help Carl with his work, if only in small ways, and Carl was only too happy to oblige.

In many ways Emma was preparing to be ‘the good wife’ in similar vein to those recommended to young ladies by the weekly magazines. ‘The ideal wife,’ wrote Rudolf von Tavel in the monthly Wissen und Leben, ‘should live and act entirely in her husband’s spirit. She must support him in his task, softening him, warming him, and praising him in golden terms, convincing her children of the same, so that the way of life in the family is the right one, fostering the right social attitudes for the upholding of the Vaterland.’ Rosa Dahinden-Pfyl agreed, writing in Die Kunst mit Männern Glücklich zu Sein (The Art of Being Happy with a Man): ‘The happiness and lasting power of married love relies largely on the good and clever ways of the woman.’ She should never complain about the husband’s coldness towards her, whether real or imagined. She should take a gentle interest in everything which concerns him, always showing her appreciation, and make his home comfortable, never tiring him with needless chatter. She should avoid becoming bitter about his weaknesses, and never meddle in his business affairs. To remain attractive to him she should always be sweet-tempered, dress nicely and with good taste; in fact, always take care of her appearance but also her health, her character and her soul. ‘Should her physical charms fade, she should retain her husband’s interest by her sympathy, her learning, her heart and spirit, but never by showing a knowledge greater than his.’

Had Emma married her haut-bourgeois beau this would surely have been her whole life, and nothing more. But not with Carl. His own childhood had nothing bourgeois about it and his own character was not suited to fitting in with convention. His requirements of Emma would be infinitely more complex and challenging than any handbook on marriage could encompass. But all that came later. For the time being it was simply exhilarating for Emma to be with someone who brought her books and scientific articles to read and was happy to discuss his plans and ideas with her.

Carl and Emma easily fell into the roles of teacher and student. Carl had already completed five years of medical studies and embarked on the work and profession that would occupy him for the rest of his life. At this time he was working on his doctoral dissertation, ‘On the Psychology and Pathology of So-called Occult Phenomena’, investigating the uncharted world of the unconscious through the evidence he had gathered during Helly’s seances at Bottminger Mill. Herr Professor Freud in Vienna had just published a book called The Interpretation of Dreams, which investigated the unconscious from a different angle, the hidden meaning of dreams, which had often filled the pages of literature but had never yet been scientifically investigated, and Carl had been deputed by Bleuler to read it and present his findings to the Burghölzli staff at one of their evening meetings. As if he didn’t already have enough paperwork to do. But this was different. This was the new world, just waiting to be discovered.

To Emma, Carl was worldly and sophisticated and, as his friend Albert Oeri described, he was a mesmerising talker. So Emma might have been surprised to discover that her fiancé had absolutely no experience of women. ‘He didn’t think much of fraternity dances, romancing the housemaids, and similar gallantries,’ recalled Oeri, making Carl sound like a bit of a prig. He did bring Luggi, Helly’s older sister, to some dances, but Oeri only remembered one occasion when Carl was really smitten, at another fraternity dance, with a young woman from French-speaking Switzerland, at which point he began to behave very oddly indeed. In fact, if Oeri had not been such a reliable witness, one would wonder at the veracity of the story. ‘One morning soon after,’ Oeri wrote, ‘he entered a shop, asked for and received two wedding rings, put twenty centimes on the counter, and started for the door.’ Presumably the twenty centimes were by way of a deposit. When the owner objected, Carl gave back the rings, took his money and left the shop ‘cursing the owner, who, just because Carl happened to possess absolutely nothing but twenty centimes, dared to interfere with his engagement’.

With anyone else you might think this was some kind of student prank, but not with Carl, hovering precariously between two personalities and having no idea how to handle such a situation. Afterwards ‘Carl was very depressed,’ said Oeri. ‘He never tackled the matter again, and so the Steam-Roller remained unaffianced for quite a number of years.’ Until he met Emma, in fact, and persuaded her to marry him.

But Emma had a secret of her own. When she was twelve her father started to lose his sight. Soon he could no longer read for himself, and Emma, the studious one, was deputed to sit and read out loud to him: newspapers, magazines, books, business matters brought over from the factory and foundry nearby, so she became quite knowledgeable in financial matters and the handling of accounts. Later, as his condition worsened, plans for the redevelopment of the Ölberg estate were made for him in Braille. It was hard for Emma, not least because her father was a difficult, sarcastic man – a trait which got worse with age and the advance of his illness. Harder still was the fact that the cause of his blindness had to be kept secret, such was the shame and stigma attached to it: Herr Rauschenbach had syphilis. According to the family, he had caught the disease after a business trip to Budapest, presumably from a prostitute. Bertha had decided not to go with him on that occasion because she felt the two little girls were too young to be left alone with the children’s maid. Had she gone, everything might have been different. It was a tragedy for the family, and photographs of Emma during her teens show a shy, round-faced, podgy girl, surely feeling the stress of the family secret. She was trying her best to help her mother with this awful burden as her father became more and more bitter and desperate, shut away from the world in his room upstairs. It robbed Emma of her sunny nature, making her too serious for her age.

Albert Oeri remembered visiting the Jung household not long before Pastor Jung died and described how Carl, aged twenty, carried his father ‘who had once been so strong and erect’ around from room to room ‘like a heap of bones in an anatomy class’. Emma sat at her father’s side reading to him as he went blind, bitter and half mad. There was not much to choose between them.

By the end of the nineteenth century doctors were finally on the verge of finding a cure for syphilis, but not soon enough for Herr Rauschenbach. By 1905 Fritz Schaudinn and Erich Hoffmann in Berlin had identified the causative organism, the microbe Treponema pallidum, and by 1910 Dr Paul Ehrlich, director of the Royal Prussian Institute of Experimental Therapy in Frankfurt, developed the first modestly effective treatment, Salvarsan, though it was not until the discovery of penicillin in the 1940s that a cure was certain. In the 1890s the treatment still relied on the use of mercury, which could alleviate the condition if caught early enough though the side effects were extremely unpleasant, and it was not a cure. Syphilis, highly infectious and primarily transmitted through sexual contact, had stalked Europe for centuries, causing fear and dread and giving rise to a great deal of moralising about the virtues of marriage. The symptoms were horrible, the first signs being rashes and pustules over the body and face, then open suppurating lesions in the skin, disfiguring tumours and terrible pain, only alleviated by regular doses of morphine. Some of the most tragic cases were those of unsuspecting wives infected by their husbands, in turn infecting the unborn child. Wet nurses were vulnerable, either catching it from the child, or, already infected themselves, passing it on to the child instead. To make matters worse for families like the Rauschenbachs, society was hypocritical about syphilis. Everyone knew about the disease but it was not talked about, except in the medical pamphlets read in the privacy of a doctor’s surgery: ‘The woman must submit to her husband – consequently, whereas he catches it when he wants, she also catches it when he wants! The woman is ignorant . . . particularly in matters of this sort. So she is generally unaware of where and how she might catch it, and when she has caught it she is for a long time unaware of what she has got.’ Another pamphlet concentrated on women of the lower classes, unwittingly revealing a further hypocrisy of the times: whilst the bourgeois woman was seen as the victim, the working-class woman, not her seducer, or client if she was a prostitute, was to blame: ‘The woman must be told . . . Every factory girl, peasant and maid must be told that if she abandons herself to the seducer then not only does she run the risk of having to bring up the child which might result from her transgression, but also that of catching the disease whose consequences can make her suffer for the rest of her life.’

In Vienna, Sigmund Freud was investigating the psychological effects of syphilis on the next generation, finding that many of his cases of hysteria and obsessional neurosis, such as his patients ‘Dora’ and ‘Rat Man’, had fathers who had been treated for syphilis in their youth. It is possible that Bertha Rauschenbach was keen on Carl Jung as a suitor for Emma not only because she could see how well suited they were, but because Carl had just completed his medical studies and could help with the treatment of her husband’s illness, in secret, in the privacy of their own home. And she was no doubt relieved to realise how little experience her future son-in-law had had with women.

Meanwhile Carl was working at the Burghölzli, putting his father, who had died ‘just in time’ as his mother said, behind him. But he could not leave Personality No. 2 behind. Years later his friend and colleague Ludwig von Muralt, the other doctor at the Burghölzli when Carl arrived, told him that the way he behaved during those first months was so odd people thought he might be ‘psychologically abnormal’. Jung himself described experiencing feelings of such inferiority and tension at the time that it was only by ‘the utmost concentration on the essential’ that he managed not to ‘explode’. The problem was partly that Bleuler and Von Muralt seemed to be so confident in their roles, whereas he was completely at sea in this strange new world of the institution, and partly because he felt deeply humiliated by his poverty. He had only one pair of trousers and two shirts to his name and he had to send all his meagre wages back to his mother and sister, still living on charity at the Bottminger Mill. The humiliation was accompanied by a general feeling of social inferiority, heightened by the fact that Von Muralt came from one of the oldest and wealthiest families of Zürich.

They were the same feelings which had often plagued Carl in the past and his solution was the same: to withdraw into himself and become what he called a ‘hermit’, locking himself away from the world. When he was not working, he read all fifty volumes of the journal Allgemeine Zeitschrift für Psychiatrie, cover to cover. He said he wanted to know ‘how the human mind reacted to the sight of its own destruction’. He might have used his own father as an illustration. Or himself during those first months of 1901 after Emma had refused his hand in marriage, perhaps the real reason why he was so distressed, when his confident Personality No. 1 disappeared into thin air along with all his hopes and dreams, and he was close to a mental and emotional breakdown, as he had been in the past and would be again in the future.

The crisis was extreme. But then, quite suddenly, at the end of six months, he recovered. In fact, he swung completely the other way, the inferior wretch replaced almost overnight by the loud, opinionated, energetic Steam-Roller of old. Once betrothed and sure of Emma’s love, Carl was able to take life at the Burghölzli at full tilt, with the kind of energy which left others breathless. No one could fail to notice it, but no one knew the reason why, because no one knew where he went every Sunday on his day off.

Not knowing of Carl’s extreme crisis of confidence, Emma remained dazzled by his love, hardly able to believe it was true. She worried that she was a boring companion as she recounted small details about her mundane week – the riding, the walks by the Rhine, the family visits, her father’s deteriorating health, the musical evenings which her mother liked to host at Ölberg. The best moments were when they discussed the books she’d been reading, which gave her week its shape and purpose, enabling her to be ‘herself’ in a way which would otherwise have eluded her. To her joy Carl was delighted by her progress, always encouraging her to do more. And to her relief she soon discovered he was not in the least interested in having a bourgeois wife who thought of nothing but home and children and life within the narrow confines of Swiss society. Every day she waited for the postman, struggling up the hill to Ölberg on his bicycle, bearing another letter from Carl addressed to ‘Mein liebster Schatz!’ – my darling treasure – long letters, filled with Burghölzli news, ideas and suggestions for further reading, and telling her how much he loved her. And every Sunday, as Carl got to know Emma better, he found that beneath the shyness and seriousness there hid another Emma: one with a lively sense of humour, who could laugh and laugh. And who better to make her laugh than Carl?

The Burghölzli at the turn of the twentieth century under the directorship of Bleuler was a remarkable institution rapidly gaining an international reputation. At a time when most asylums simply removed the insane from society, locking them up, often for whole lifetimes, the Burghölzli offered treatment of various kinds and tried, as far as possible, to show the patients consideration and respect. Jung himself describes the situation:

In the medical world at the time psychiatry was quite generally held in contempt. No one really knew anything about it, and there was no psychology which regarded man as a whole and included his pathological variations in the total picture. The Director was locked up in the same institution with his patients, and the institution was equally cut off, isolated on the outskirts of the city like an ancient lazaretto with its lepers. No one liked looking in that direction. The doctors knew almost as little as the layman and therefore shared his feelings. Mental disease was a hopeless and fatal affair which cast its shadow over psychiatry as well . . .

Soon after Jung joined the staff numbers increased to five doctors, and as far as Bleuler was concerned five was a luxury; before he took the job of director of the Burghölzli in 1898 he had spent thirteen years as director of the lunatic asylum on the island of Reichenau, where there were over 500 inmates with only one trained medical assistant.

Eugen Bleuler was a remarkable man. Coming from Swiss peasant stock, he was the first of his family to attend university, and, much like Jung, he was drawn to this new branch of medicine because he had experience of mental illness in his own family. His sister, Pauline, was a catatonic schizophrenic and after Bleuler married in 1901 she lived with him, his wife and their eventual five children in a large apartment on the first floor of the Burghölzli. Bleuler had trained with some of the most progressive practitioners of the age, including Dr Jean-Martin Charcot at the Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris, where Sigmund Freud also spent time. Charcot was first and foremost a neurologist concerned with the functions and malfunctions of the brain, demonstrated with a showman’s flair to the hundreds of students who flocked to his lectures from England, Germany, Austria and America. He followed his patients’ progress throughout their lives and when they died he examined their brains under the microscope, making early diagnoses of Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis, motor neurone disease and Tourette’s. But it was his patients suffering from hysteria who interested him most and brought him his greatest fame. The fashionable ‘treatments’ at the time for hysteria were ‘animal magnetism’ and hypnotism, each requiring a doctor with special ‘intuition’. In animal magnetism the doctor passed his hands over the patient to release the vital fluid or energy which had supposedly become blocked. In hypnotism the doctor took control of the mind, providing the most dramatic demonstrations as patients fell into trances and spoke in strange voices. When Eugen Bleuler continued his training under Auguste Forel at the Burghölzli in the early 1880s, hypnotism was one of the main treatments and Forel had his own ‘Hypnosestab’, a wand with a silver tip which he used with some success on obsessives and neurotics as well as hysterics. But his greatest success was with alcoholics. The Burghölzli was then, and remained when Bleuler took over from Forel, an institution which held strictly to the virtues of abstinence. Drink was one of the worst afflictions of the age and asylums were full of chronic cases who were contained whilst ‘inside’, but, without a vow of abstinence, soon reverted to old habits once they left.

All this Carl explained to Emma in his letters, or on their Sundays in the drawing room at Ölberg, or on their afternoon walks high up in the meadows above the house, up to ‘their’ bench by the edge of the forest beyond. Later Emma confessed she only understood half of it at the time. Apparently Bleuler was continuing the progressive methods he had started to develop at Reichenau: staff lived amongst the inmates, eating with them at the same tables and socialising with them in their spare time. His theory of affektiver Rapport, listening with empathy, was the guiding principle. There was also a great emphasis put on cleanliness. Inmates were helped to wash thoroughly, in spite of a shortage of baths and bathrooms, and to keep their clothes in good order; likewise their beds, a dozen on each side of a ward, which were kept neat, the heavy feather covers hung out of the windows every morning to air and the mattresses regularly turned. The patients were kept occupied, Herr Direktor Bleuler believing that physical activity was good for the distraught mind. The kitchen gardens lay beyond the walls of the asylum extending down the slopes and provided all their vegetables and fruit, which were brought fresh to the kitchens every day. The dairy produced the milk and cheese. Hens provided the eggs. The laundry kept inmates busy washing and starching and ironing. The Hausordnung kept the building spick and span, smelling of floor polish and soap. There were workshops: woodwork and wood-chopping for the tiled stoves in winter, sack-making, silk-plucking, sewing, mending, knitting. The place was to all intents and purposes self-sufficient and the food, for an institution, was good: always a soup for the midday meal followed by meat and vegetables, with soup and bread again for the evening meal along with a piece of cheese or sausage. The patients were divided into three categories and while third-class patients did not eat as well as the first-class (private) ones, it was still a better standard than at most asylums. In the evenings there were card games, reading, concerts; sometimes the patients produced an entertainment, sometimes lectures were put on, and at the weekends there were occasional fetes and dances for those willing and able. Jung was put in charge of social events as soon as he arrived. He hated it.

To keep things going day to day there were seventy Wärters, male and female helpers in long white aprons and starched white collars, the men in trousers, shirt and tie, the women in long dark skirts and starched white caps. Like the doctors they lived on the premises, but unlike the doctors they had no quarters of their own. They slept on the wards or in the corridors, on wooden camp beds put up for the night, the women in the women’s section, the men in the men’s. The only exception was the Wärters in charge of the ‘first-class’ patients, who would sleep in the patient’s private room. This was a great privilege because not only was there some peace and quiet but the private patient was allowed candles in the room at night, or even an oil lamp if their behaviour was good enough and they were no danger to themselves or others. It was an eighty-hour week and the pay was low: 600 Swiss francs per annum for the male Wärters, a hundred francs less for the women. But board and lodging was all found, so the rest could be saved.

Carl’s day started at 6 a.m. and rarely finished before 8 p.m., after which he would go up to his room to write his daily reports, work on his dissertation, and compose his daily letter to Emma. There was a staff meeting every morning, after a breakfast of bread and a bowl of coffee, ward rounds morning and evening, an additional general meeting three times a week to consider every aspect of the running of the institution, and at least once a week a discussion evening, which, by the time Carl joined, was already well versed in the writings of Freud. Once into his stride there was no stopping Herr Doktor Jung, and his sheer brilliance soon singled him out. Bleuler’s affektiver Rapport was exactly the kind of treatment he himself believed in: listening acutely and with empathy to the apparent babblings of inmates with dementia praecox, or the outbursts of hysterics and the circular repetitions of obsessive neurotics. Carl was fascinated by the chronic catatonics who had been at the Burghölzli for as long as anyone could remember, including the old women incarcerated since they were young girls for having illegitimate children, who no longer knew who they’d once been.

Carl could listen to his patients for hours, taking notes, catching clues, watching how the mind worked. The Burghölzli was known for its progressive research, and inmates demonstrating interesting symptoms were the willing, and unwilling, guinea pigs – ushered into the room or lecture theatre for the doctor to examine, question and offer a diagnosis. It was a fine apprenticeship for Carl, as he himself admitted. He had little interest in the patients who were there with TB or typhus, and he could not bear the routine work, the meetings and the administration, to which he rarely gave any proper attention. But the old lady who stood by the window all day waiting for her long-lost lover, or the schizophrenic who talked crazily about God – that was a different matter altogether. Here his Personality No. 2 came into its own, working hand in hand with No. 1. ‘It was as though two rivers had united and in one grand torrent were bearing me inexorably towards distant goals,’ he later wrote. Bleuler soon saw that Herr Doktor Jung, with his fine intuition on the one hand and his brilliant mind on the other, understood the inmates like no one else.

Carl’s listening was made more effective by Bleuler’s insistence that everything be conducted in Swiss dialect, not the High German which doctors normally used, and which effectively meant no communication since most inmates could not understand High German, and even if they could, it caused such a social gulf between doctor and patient that the patient felt browbeaten. When speaking High German, Carl retained his broad Basel accent, something which had humiliated him at grammar school, but no longer. Now he learnt all the other regional Swiss dialects as well because at the Burghölzli it was expected that the doctor should adapt to the patient, not the other way round, an idea generally held as odd and even dangerous by the vast majority of the medical profession. Besides, without it Jung could do no useful research.

On Sundays he retold the patients’ stories to Emma, shocking her, entertaining her, keeping her spellbound. Stories about women in the asylum held a special fascination for her, such as the woman in Carl’s section who had been diagnosed with schizophrenia. Jung disagreed with the diagnosis, thinking it was more like ordinary depression, so he started, à la Freud, to ask the woman about her dreams, probing her unconscious. It turned out that when she was a young girl she had fallen in love with ‘Mr X’, the son of a wealthy industrialist. She hoped they would marry, but he did not appear to care for her, so in time she wed someone else and had two children. Five years later a friend visited and told her that her marriage had come as quite a shock to Mr X. ‘That was the moment!’ as Jung wrote in his account of it. The woman became deeply depressed and one day, bathing her two small children, she let them drink the contaminated river water. Spring water was used only for drinking, not bathing, in those days. Shortly afterwards her little girl came down with typhoid fever and died. The woman’s depression became acute and finally she was sent to the Burghölzli asylum. Jung knew the narcotics for her dementia praecox were doing her no good. Should he tell her the truth or not? He pondered for days, worried that it might tip her further into madness. Then he made his decision: to confront her, telling no one else. ‘To accuse a person point-blank of murder is no small matter,’ he wrote later. ‘And it was tragic for the patient to have to listen to it and accept it. But the result was that in two weeks it proved possible to discharge her, and she was never again institutionalised.’

Love, murder, guilt, madness. Emma had never heard stories like it. Nor had she ever considered the powerful workings of the ‘unconscious’. But she was intelligent and well read. She knew all about Faust’s pact with Mephistopheles, Lady Macbeth’s guilty sleepwalking, and Siegfried, the mythical hero. Now she was beginning to realise that this ‘unconscious’ was the key to the hidden workings of the mind and could be accessed in various ways, then used as a tool to cure the patient. By the time of their secret betrothal Emma was helping to write up Carl’s daily reports, learning all the time. If these years were the beginning of Carl Jung’s career, they were the beginning of something for Emma too.

Meanwhile Jung was trying, between his eighty-hour week and his social duties, to finish his dissertation on the ‘So-called Occult Phenomena’. There had been a revival of interest in the occult at the end of the nineteenth century, people using Ouija boards and horoscopes, having seances, delving into magic and the ancient arts, and reporting strange paranormal occurrences. Carl was used to such things from his mother’s ‘seer’ side of the family, like the time when a knife in the drawer of their kitchen cupboard unaccountably split in two, or the times when his mother spoke with a strange, prophetic voice. But what interested Jung the doctor was the way the occult provided another route to the hidden world of the unconscious, more psychological than spiritual. Cousin Helly was probably a hysteric, he now concluded, a young girl falling into trances to get attention. In fact Helly’s mother had become so worried about the way the trances and the voices were dominating her life that she had packed her off to Marseilles to study dress-making, at which point Helly’s trances stopped, and she became a fine seamstress.

Jung presented his dissertation to the faculty of medicine at the University of Zürich in 1901 and it was published the following year. The Preiswerk family, reading it on publication, were distressed. After a general introduction about current research on the subject, Jung concentrated on one case history: Helly Preiswerk and her seances at Bottminger Mill, referring to her, by way of thin disguise, as Miss S. W., a medium, fifteen and a half years old, Protestant – that is, instantly recognisable by anyone who knew the family. She was described as ‘a girl with poor inheritance’ and ‘of mediocre intelligence, with no special gifts, neither musical nor fond of books’. She had a second personality called Ivenes. One sister was a hysteric, the other had ‘nervous heart attacks’. The family were described as ‘people with very limited interests’ – and this of a family who had come to the rescue of his impoverished mother and sister. It showed a side of Carl which Emma would have to deal with often in the future: a callous insensitivity, driven perhaps by what he himself admitted was his ‘vaulting ambition’. But as far as the faculty of medicine at the University of Zürich was concerned, it was a perfectly good piece of research, fulfilling the aims Jung expressed in his clever conclusion: that it would contribute to ‘the progressive elucidation and assimilation of the as yet extremely controversial psychology of the unconscious’.

The most telling thing about the dissertation is the dedication on the title page. It reads: ‘to his wife Emma Jung-Rauschenbach’. Given the dissertation was completed in 1901 and published in 1902, the dedication precedes the event of the marriage by a good year. Whatever was Carl thinking? What is the difference between ‘my wife’, which Emma was not, and ‘my betrothed’, which she was. It suggests Carl was desperate to claim Emma for himself, fully and legally, a situation which mere betrothal could not achieve. Emma was the answer to all Carl’s problems: financial – certainly – but equally his emotional and psychological ones. He needed Emma for his stability in every sense, and he knew it.

Carl and Emma’s wedding was set for 14 February 1903, St Valentine’s Day. Buoyed up and boisterous, Carl became increasingly impatient and intolerant of the ‘unending desert of routine’ at the Burghölzli. Now he saw it as ‘a submission to the vow to believe only in what was probable, average, commonplace, barren of meaning, to renounce everything strange and significant, and reduce anything extraordinary to the banal’. Given Bleuler’s achievements at the asylum this was high-handed Carl at his worst. The fact is, he was fed up. He wanted to take a sabbatical, to travel, to do things he had never been able to do before. And he wanted to do it before he married Emma. Because he had no money of his own, his future mother-in-law happily offered to fund it. In July 1902 Jung submitted his resignation to Bleuler and the Zürich authorities, and by the beginning of October he was off, first to Paris, then London, for a four-month pre-wedding jaunt. Bleuler, knowing nothing of Jung’s secret betrothal to Fräulein Rauschenbach, must have been angry and non-plussed. How would Herr Doktor Jung afford it? How could he manage without a salary? And what about his poor mother and sister?

Emma and her mother meanwhile started the lengthy process of preparing for the wedding – the dress itself, the veil, shoes, bouquet, trousseau, church service, flowers, guest list, menu for the wedding banquet, and the travel arrangements for the couple’s honeymoon. Emma’s father’s health must have caused some heartache: already parlous, it had taken a turn for the worse. He knew about his daughter’s betrothal to Carl now, but what to do about the wedding? It was a terrible dilemma for Emma who had, over the years, watched her father’s decline in horror and shame, and now he would not be able to attend the ceremony, or walk her up the aisle, or give her away.

Before leaving the country Carl had to complete his Swiss army military service, an annual duty for all Swiss males between the ages of twenty and fifty, in his case as a lieutenant in the medical corps. But then he was off, first paying a visit to his mother and sister in Basel on his way to France. From Paris he wrote daily letters to Emma, and separately to her mother too, giving them all the news: he lived cheaply in a hotel for one franc a day and worked in Pierre Janet’s laboratory at the Salpêtrière, attending all the eminent psychologist’s lectures. He had enrolled at the Berlitz School to improve his English and started reading English newspapers, a habit he retained all his life. He went to the Louvre most days, fell in love with Holbein, the Dutch Masters and the Mona Lisa, and spent hours watching the copyists make their living selling their work to tourists like himself. He walked everywhere, through Les Halles, the Jardin du Luxembourg and the Bois de Boulogne, sitting in cafés and bistros watching the world, rich and poor, go by, and in the evenings he read French and English novels, the classic ones, never the modern. He also saw Helly and her sister Vally, both now working as seamstresses for a Paris fashion house, and he was grateful for their company, not only because he knew no one else in Paris, but because Helly was generous enough to forgive him his past sins. When the weather turned cold Bertha Rauschenbach posted off a winter coat to keep him warm. It wasn’t the only thing she sent him: when he expressed a longing to commission a copy of a Frans Hals painting of a mother and her children, the money was quickly dispatched.

By January Carl was in London, visiting the sights and the museums and taking more English lessons. It must have been his English tutor, recently down from Oxford, who delighted Carl by taking him back to dine at his college high table with the dons in their academic gowns – a fine dinner, as he wrote to Emma, followed by cigars, liqueurs and snuff. The conversation was ‘in the style of the 18th century’ – and men only, ‘because we wanted to talk exclusively at an intellectual level’. In 1903 it was still common for men to be seen as more intellectual than women, and there were no women at high table to disagree. It was Jung’s first brush with the English ‘gentleman’ and he never forgot it, the word often appearing in his letters as a mark of the highest praise.

In Schaffhausen, Emma received a present. It was a painting. In between all his other activities Carl took the time in Paris to travel out into the flat countryside with his easel and paints. He had always loved painting, even as a child, and in future it would go hand in hand with his writing, offering a poetic and spiritual dimension to his words. He found a spot on a far bank of the River Seine, looking across at a hamlet of pitched-roof houses, a church with a high spire, and trees all along. But the real subject of the painting was the clouds, which took up three-quarters of the canvas: light and shining below, dark and dramatic above. The inscription read: ‘Seine landscape with clouds, for my dearest fiancée at Christmas, 1902. Paris, December 1902. Painted by C. G. Jung.’

It might have been a premonition of their marriage.

The painting Carl sent Emma for Christmas 1902.