Читать книгу One Big Self - C.D. Wright - Страница 7

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Stripe for Stripe

ОглавлениеDriving through this part of Louisiana you can pass four prisons in less than an hour. “The spirit of every age,” writes Eric Schlosser, “is manifest in its public works.” So this is who we are, the jailers, the jailed. This is the spirit of our age.

“You won’t be back, will you?” asked the inmate who told me he wanted to be a success.

Try to remember it the way it was. Try to remember what I wore when I visited the prisons. Trying to remember how tall was my boy then. What books was I teaching. Trying to remember how I hoped to add one true and lonely word to the host of texts that bear upon incarceration.

Something about the extra-realism of that peculiar institution caused me to balk, also the resistance of poetry to the conventions of evidentiary writing, notwithstanding top-notch examples to the contrary: Mandelstam, Akhmatova, Wilde, Valéry, Celan, Desnos, et al. After all, I am not them. She asked me to come down, my friend the photographer, and I went, and then I wanted to see if my art could handle that hoe.

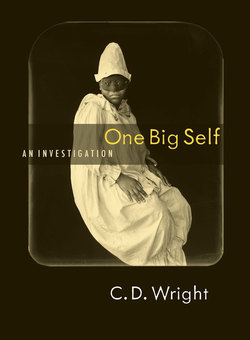

Trying to remember how my skin felt when I opened an envelope of proofs of Deborah Luster’s intimate aluminum portraits of the inmates at Transylvania (the site of East Carroll Parish Prison Farm, a minimum-security male prison, now closed); then Angola (the site of Louisiana State Penitentiary, maximum security); then St. Gabriel (the site of the Louisiana Correctional Institution for Women, the LCIW). I was electrified by the first face—a young, handsome man blowing smoke out of his nose. Behind every anonymous number, a very specific face.

On the phone my friend described to me the rich Delta grounds of Angola, 18,000 acres. Angola, where the topsoil is measured not in inches but feet. The former sugarcane plantation lies at the confluence of rivers and borderland of the unruly Tunica Hills. Grey pelicans nest on the two prison lakes, alongside the airstrip, the grading sheds, the endless fields of okra and corn. Then there’s the prison museum, the prison radio station, the prison magazine; the tracking horses and tracking dogs trained by inmates… and the tree-lined neighborhood of free-world residents, their children bused outside the fence to school. Then the immaculate cinder-block buildings that house the inmates, the administration building, and the death house; the greenhouse and extensive flower beds—take away the fencing and it resembles nothing so much as a college campus. The men in maximum number more than the men who lived in my hometown. Then there’s the geriatric unit, the award-winning hospice program; the caisson the inmates built to bear the men in the hand-built coffins to one of the two graveyards inside the prison. In the old burial ground most graves are not identified by name. The caisson is pulled by draft horses, French Quarter style. When the champion of the prison rodeo had a heart attack in the fields, a riderless horse led the final procession. The celebrated inmate’s uniform was “retired” to the prison museum.

Everything about Louisiana seems to constitute itself differently from everywhere else in the Union: the food, the idiom, the stuff in the trees, the critters in the water, and the laws, Napoleonic, not mother-country common law. The prisons inevitably mirror differences found in the free world. Where they came up with their mirrors is another mystery. (In maximum, they are made of metal.) The definition of the face is a memory.

Vivid to me is Debbie saying that at the trial of her mother’s murderer, she looked around and saw the people sitting on separate sides of the courtroom, the way they do at a wedding, the bride’s people, the groom’s people, and she tried to take in the damage radiating through the distinct lines—the perpetrator’s side, the victim’s side.

Vivid to me is leaving Angola after the first visit and Debbie asking what I thought, and I said (too fast) I thought those were the nicest people I had ever met, and the ironic laughter it provoked in us both, the car yawing. The obvious truth, people are people. Equally, the damage is never limited to perpetrator and victim. Also, that the crimes are not the sum of the criminal any more than anyone is entirely separable from their acts.

I remember an afternoon at the iron pile at Transylvania watching the men plait each other’s hair between sets at the weight bench. When I asked about a man whose face was severely scarred, a very specific face, with large, direct aquamarine eyes, a guard told me that the man’s brother had thrown a tire over his head and set it on fire. This I did not know how to absorb. It was a steaming day; the men were lifting weights and plaiting their hair.

I remember Easter weekend at the women’s prison. The day before, a long line formed outside the prison-run beauty shop. Inside, the women having their hair fixed were talking back to the soap operas on the small snowy screen. By visiting day the inner courtyard had been transformed into a theme park for the children. A trampoline had been rented, a cottoncandy machine; someone dressed in a bunny suit was organizing an egg hunt. The little girls wore starched, flouncy dresses, and the boys white jackets and black, clip-on bow ties. The women were dressed up, too, even the ones shackled at the ankle and waist. Deborah photographed all day, nonstop. Identifiable pictures of children would have to be excluded from publication, but people wanted a keepsake. We left before visiting hours ended. It wasn’t our place to be there. It wasn’t really in us to be there.

Remember sitting in the frigid Holiday Inn bar near St. Gabriel, at the end of one visit to the women’s prison, staring at the aquarium, not talking.

I talked to a man who told me he has done a lot of time. Lot of time. He should write a book, he said. He wants to be a success. “Hollywood, huh, here I come.”

I talked to a woman who said the one time her dad visited her from the Midwest, she asked him to look at her eyes. There was a look she didn’t want to get, a faraway look. Her father pretended to examine her eyes, then told her they looked like the same old peepers to him. She passed her time reading. Same way she passed her childhood. She thought she was going to be an astronomer when she grew up. Not a felon.

Both parents are dead now. Of her three sons, one disappeared, one died of suicide, and the third severed contact.

One of the inmates at St. Gabriel informed me she wouldn’t be around for visiting hours tomorrow because she was on the drill team. Also, her ex-husband would not be bringing her little boy to see her. Not tomorrow, not ever.

The grease burns, I am told by another inmate, are courtesy of her sister.

DON’T WALK ON THE GRASS, says the sign posted in the inner yard.

The coffin builder (now deceased) in the prison was so devoted to his catahoula he overfed her to the point that she could only walk side to side. She wore a red halter he fashioned for her. Sissy was the dog’s name. His name was Redwine.

The inmate who fishes one of the stocked lakes for the warden admitted that his son was in prison, too, in another state. He saw him once when he was a baby. And then, once, between sentences.

A guard pointed out a woman whose father, mother, uncle, brother, sister were all locked up, two were at Hunt, two here, and one at Big Gola. Her sister was her fall partner. It made you wonder who was left to look after the dog.

That day Debbie was photographing mothers and daughters, and twins.

Another guard told me he had made the mistake he had most dreaded making, delivering the execution letter, setting the date and the time, to the wrong man on death row.

In some prisons, you can’t have a last cigarette, but Valium is permitted.

I heard about a petition in a town out West to take back the night sky. The locals thought they were getting a second minimum-security prison, an economic pick-me-up. Instead, a supermax sprang up, that perverse marriage of mind and technology. Lights from the new institution burn so intensely the stars have gone dark on them.

Then there’s the bus that leaves from Monroe taking visitors to one of four neighboring pens, Al Derry’s Prison Transport and Popcorn Balls. Evidently, the popcorn balls make it the competitive ride. Only in Louisiana.

After a time. A lot of time. They stop coming. The free-worlders. They are too poor or too busy working or are already looking after others on the outside or their car is broken or they are too worn down or they move too far off or they get old, sick, and die. So the inmates wait for their turn.

They aren’t going anywhere. They have all the time there is.

“The only continuity of our lives,” wrote Malcolm Braly, American writer, American lifer, “was that we had none.”

“Waiting,” goes the motto at St. Gabriel, “it’s the LCIW way.”

I wrote a woman and asked if she ever had any pets. She wrote back: Bandit, Baby, Snobby, Elsie, Bear (those were the dogs). Tiger and Fuzzball (the cats), Jill, Ben, and Junior (the coons). “And a lot of unnamed fish, hamsters, rabbits, chickens, ducks, geese, guinea pigs, and a deer, not really a pet but I finally coaxed to the point she would eat out of my hand.”

Not to idealize, not to judge, not to exonerate, not to aestheticize immeasurable levels of pain. Not to demonize, not anathematize. What I wanted was to unequivocally lay out the real feel of hard time. I wanted it given to understand that when you pass four prisons in less than an hour, the countryside’s apparent emptiness is more legible. It is an open, running comment when the only spike in employment statistics is being created by the supply of people crossing the line.

I wanted the banter, the idiom, the soft-spoken cadence of Louisiana speech to cut through the mass-media myopia. I wanted the heat, the humidity, the fecundity of Louisiana to travel right up the body. What I wanted was to convey the sense of normalcy for which humans strive under conditions that are anything but what we in the free world call normal, no matter what we may have done for which we were never charged.

The world of the prison system springs up adjacent to the free world. As the towns decline, the prisons grow. As industries disappear, prisons proliferate, state-funded prison-building surges are complemented by private-investment promising “to be an integral component of your corrections strategy,” according to an industry founder. The interrelation of poverty, illiteracy, substance and physical abuse, mental illness, race, and gender to the prison population is blaring to the naked eye and borne out in the statistics. Of the developed nations, only Russia approaches our rate of incarceration. And the Big Bear is a distant second. Ladies and Gentlemen of the Jury, the warp in the mirror is of our making.

The popular perception is that art is apart. I insist it is a part of. Something not in dispute is that people in prison are apart from. If you can accept—whatever level of discipline and punishment you adhere to momentarily aside—that the ultimate goal should be to reunite the separated with the larger human enterprise, it might behoove us to see prisoners, among others, as they elect to be seen, in their larger selves. If we go there, if not with our bodies then at least our minds, we are more likely to register the implications.

I am going to prison.

I am going to visit three prisons in Louisiana.

I am going on the heels of my longtime friend Deborah Luster, a photographer.

It is a summons.

All roads are turning into prison roads.

I already feel guilty.

I haven’t done anything.

But I allow the mental pull in both directions.

I am going to prison in order to write about it. Like a nineteenth-century traveler.

Kafka put it this way, “Guilt is never to be doubted.”

Also: behind every anonymous number, a very specific face.

Also: there are more than two million individuals, in this country, whose sentences have rendered them more or less invisible. Many of them permanently.

First to Transylvania. Then Angola. Then St. Gabriel. These are their place-names.

Over the next year and a half Deborah Luster will photograph upwards of 1,500 inmates.

I will make three trips.

It is an almost imperceptible gesture, a flick of the conscience, to go, to see, but I will be wakeful.

It is a summons.

C.D. Wright