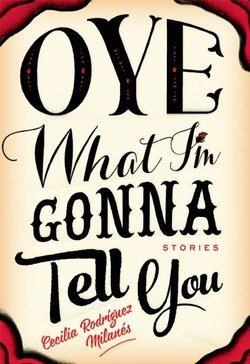

Читать книгу Oye What I'm Gonna Tell You - Cecilia Rodríguez Milanés - Страница 10

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

ОглавлениеENOUGH OF ANYTHING

Alma grew up around whores and homosexuals. Because her mother was dead, she, along with her younger brother, Ricardo, lived in a boarding house run by their great aunt Lázara in a poor barrio in the east of Havana. Lala—as Lázara was known to all—was less indiscriminate than she was disinterested in the quality of the roomers who lived in the four single room apartments on the second floor, furnished with beds, hot plates and a shared toilet. Alma and Ricardo lived downstairs with tía Lala. They had three rooms—a big bedroom they all shared, a rarely-used sitting room, and a long, narrow kitchen with a back door leading to the toilet and a small yard.

In the front of the house was a half-enclosed balcony facing the street. Here, Lala spent her days smoking puros and drinking café she warmed on an ancient burner that worked better than the new ones the roomers had. From her perch, she kept track of the comings and goings of the tenants. Lala genuinely liked her tenants, as long as they kept out of trouble and paid their rent, that is. The longest staying roomer was Rosalinda, who Lala called “la pobre Rosalinda who is neither pretty nor smells like a rose” but never to her face.

Alma liked it when the roomers washed up and came downstairs with their wet hair still grooved with wide comb marks, shirts or shifts clinging to their bodies and always sweetly crisp-smelling. Sometimes, Rosalinda would give her three pennies to braid her long black hair in a neat plait that almost reached her tailbone. On Fridays, Marco, the most recent roomer whose blond hair was always perfectly coifed, sent Alma to the bodega for rolling papers and let her keep the whole five cents change; errands were a way tenants could tip the children and show Lala their appreciation. Lala permitted the roomers’ affection toward the siblings because she was stingy with hers. She didn’t like anyone touching her, though on occasion she allowed Alma to rub her plump little feet and sausage-like toes.

Sometimes one or two of the roomers would come downstairs to gossip, sitting or standing on the steps next to the balcony. They would call their landlord Doña Lala and tell dirty jokes or stories that Alma and her brother were warned by their aunt never to repeat at school. By the time she was nine years old, Alma understood all the components of sex, though she couldn’t fathom how people could enjoy such acts, especially the kind requiring the unusual use of one’s hindquarters. This knowledge gained Alma a measure of popularity at school when it was evident that no one else knew as much as she did. Even the older girls who had boyfriends named her la profesora of sexual studies.

“Oye, niña, what have you learned from your scandalous neighbors recently?” Three upper grade girls formed a circle around her.

Alma smiled broadly and, pointing to each girl at a time, said, “That your father likes to take it up the ass. That your father likes to put it there. And that your father likes to watch.”

The girls erupted in howling laughter and curses.

“You shameless . . .”

“You sucia . . .”

“Hija de puta!” That was the one that stopped Alma in her tracks. Everyone knew where the line was. Her mother was not a whore. She was dead.

“I’m so sorry, I’m sorry.” Micaela’s hand shot up to her red painted lips as she stepped away. “I didn’t mean it.” The girl’s friends moved to push her further back. They nodded to Alma, signaling that they would attend to Micaela’s transgression, who continued apologizing even after Alma was out of earshot.

Alma and Riqui (a nickname her brother gave himself after eschewing the perennial Ricardito) attended a local public school in one of the suburbs of Havana with a mix of mid and lower working class folks. While they had the same full lips and wispy dark hair, they did not look like siblings, and the lighter-skinned Riqui liked to point out that he was the more guapo. Alma secretly agreed while protesting that his shapely legs were “such a waste on a boy.”

Their aunt praised their “equal beauty” and made sure their uniforms were clean and starched stiff, always checked their head for lice, and fed them sufficiently, including a weekly swill of cod liver oil. Lala never let them walk around barefoot, declaring loudly she would not tolerate “worm-infested brats in her house” and forbade pets for the same reason. Alma could not conceive of how worms could get inside her body from her feet or a puppy, but she was an obedient girl who never questioned her aunt’s authority. Riqui, a contrary boy famous for his on-call farts, wasn’t ever spanked, only mildly scolded.

Their Mamá had been tía Lala’s and tía Orfa’s beloved and beautiful only grandniece Gladys. Tía Lala and tía Orfa used to live upstairs before there were any boarders and before Mamá was abandoned by her own mother. Alma knew only two things about her grandmother, who Lala derisively called “la estrella”: that she worked in a casino and would wake them all up in the middle of the night so they could eat the food she’d brought home while it was still warm; and that she ran away with an americano to el norte to make movies. As for tía Orfa (who died of being old), Alma remembered very little, only that she had a broad dark stain that covered her right eye and cheek, like she had splashed that part of her face with reddish brown paint. Alma was still an only child when Orfa died, but old enough to fear kissing the birthmark. And Mamá, well, she remembered some things but more often she felt her as a persistent, sad ghost pressing on her absurdly flat chest.

Lala had helped tía Orfa, a respected yerbera, with Alma’s birth, a five pound runt of a baby, but by the time the nine-pound beast Riqui was kicking his way out of Mamá, Lala was alone. She knew some herbs could ease the labor, but concentrated hours massaging Mamá’s belly for the baby to turn around. After much struggle and screaming, Lala successfully helped Mamá bring Riqui to light but, what with all the difficulty of the labor and the size of the purple baby boy whose piercing cries could summon the dead, she forgot everything else that had to be done after cutting the umbilical cord so that some of the placenta stayed inside and there was a fatal infection.

In their bedroom was a big photo of Mamá in a tin cut frame next to an even bigger one of Our Lady of Regla. Lala made them pray to both every night, even though Riqui usually fell asleep before the second Hail Mary and Lala was snoring by the first Our Father. The blessed mother of the oceans’ face smiled serenely in her blue gown, hands out at her sides, light rays shining all around, the sea sparkling behind her. She looked like a loving mother who would enfold you and grant any little thing you asked for, if what you wanted was pure.

Her mother’s portrait lit by candles was a stark contrast. Alma would study her face; she had the same delicate curls and almond eyes but couldn’t tell from the black and white photo what color they were. There seemed to be a melancholic expression at the corners of her closed mouth, and Alma wondered whether she knew she was going to die so young. Alma couldn’t help blaming Riqui a little, though mostly she was jealous of the tenderness with which tía Lala occasionally treated him. But then again, Riqui couldn’t remember what it was to smell Mamá’s sweet neck or feel her soft fingertips circling her back as Alma did when they had nestled together every night.

Their father was even more of a ghost, an itinerant brush salesman who visited occasionally, then never returned, not even once to see his motherless baby boy; the only thing he left them was his last name, Delgado, which Lala regularly cursed. Alma couldn’t remember what he looked like and there were no photos of him anywhere, though given Lala’s influence she imagined him with horns and a forked tongue.

“Lala, why didn’t you have children?” Alma asked one day after her best friend Loly started menstruating, claiming that she was now capable of bearing children, something Alma seriously doubted since her breasts were even flatter than hers. Alma was fifteen but hadn’t yet started and probably wouldn’t for a long time because she was so skinny. Jorgina, one of her classmates, thought she was being instructive when she showed a clutch of girls in the bathroom what the little towels looked like. Alma had already seen some used ones Rosalinda or Consuelo had discarded on the trash heap in the yard before Lala told them to be more discreet after Riqui brought one to the front porch to inspect.

“Pelucita, hija, el señor blessed me with the burden of raising my sainted niece and then her children,” she said, then gestured for the girl’s hand. “You will have your own children someday but not for a long . . .” She stopped short, biting her lip till teeth marks showed and Alma wondered if a burden could also be a blessing.

In tenth grade, Alma fell in love with Eduardo Domínguez, a poor classmate from around the way who knew how to do many of the acts Alma only knew how to describe, even some requiring the unusual use of one’s hindquarters.

“Pelucita, meet me at the midday break,” Eduardo whispered from behind her as they switched classes one morning. A chill shot down her spine as she nodded. His large-lidded eyes were wider today, she noticed. She bit her lip in anticipation of his fondling and it was difficult to sit still in the last class of the morning.

Alma found him near the walking ficus trees; he liked to pretend he was in jail behind the vines that had fastened to the ground. His crooked smile looked especially handsome to her; Loly didn’t think he was, pointing to the missing canine and bowed legs but these things endeared him all the more to Alma.

“Mi amor,” he reached to pull her behind the widest trunk, his big hands already moving over her.

“We only have a few minutes,” Alma’s smile tilted up just as her shoulder did.

“I know, I know. But we’ll leave the loving for later.” He kissed her forehead. “I have something to propose to you.”

Alma’s thin eyebrows arched.

“Here, let’s sit down. Let me tell you what I have been thinking about.” Eduardo’s face was seized by excitement. “Querida, what would you say if I asked to you go with me to Oriente? Wait!” He held his hand up before Alma could interject. “I want us to be together all the time. It’s impossible for me to concentrate on school when all I think about is being with you, holding you, playing with you until you scream with pleasure.”

Alma had surprised herself with the first yelp that had escaped her lips when his suckled her. It was now his goal to elicit all matter of cries from her during their encounters. She bit her lip and let him continue.

“We could leave this place and become free! New people!”

Was it possible to become a new person in a new place, she wondered?

“No one to tell us what to do. I could work for us, for you! I’ll do anything, cut caña, shine shoes even if I have to but it won’t be like that. I promise, mi vida. It will be wonderful, an adventure. Imagine it, Alma mia!” He explained how they would make their escape, hopping aboard the westbound freight train that left before dawn from the yards nearby, riding in front of the sun and towards their destiny. He told her about the famous days-long carnavales that wound through the streets of Santiago de Cuba. He pointed out that the most important musicians came from that end of the island. She mentioned money; he said he had some, not a lot but enough. She asked when and he said, “Whenever you are ready.”

“My love, with you, always but . . . give me a few days to earn some more pennies to add to yours.” She kissed his hands that firmly grasped hers.

“As you say.”

They parted and didn’t even exchange glances in their only class together. Alma’s blood raced and she felt warmth throughout her limbs while her heart thumped steadily with the promise of a different life.

Alma had every intention of dropping out of school. She could happily see herself running off with Eduardo to Santiago where, he reminded her, the music and dancing was the best on the island. However, a frantic Loly told on her to all the teachers. Señorita Álvarez, one of the more concerned ones, unafraid of their dicey neighborhood, went to talk to Lala, who started cursing as soon as she saw the teacher coming up the street.

She called Alma out to the porch. “What is the meaning of this, niña?” she said through teeth locked on a cigar butt.

“I don’t know, tía Lala,” Alma had already hidden a little piece of cloth in the back of the armoire, wrapping her only blouse and skirt without faded patches or stains, her sandals, some barrettes and Mamá’s comb.

“If you have done anything!” Lala raised her hand high, threatening the violence Alma had personally never experienced but had witnessed, having seen tía thrash half-dressed men who mistreated her roomers going down the stairs out into the street where everyone taunted the fleeing “degenerates.” Shouts of “maricón” or “animal” would follow the singled-out man until he turned the corner and was out of the neighbors’ view.

Lala hiked up her prodigious breasts and slowly made her way down the stairs to the street. She had no intention of letting the teacher in the house without a good reason.

“What is it that you want?”

“Buenas tardes, señora. I come about the girl. Is it possible to speak inside?”

Lala wagged her finger from side to side, then gestured for Alma, already shaking with hot tears slipping down her cheeks, to go inside. Alms considered grabbing her bundle and running out through the rear of the house, though that would require climbing over the fence into the mechanic’s yard where a big German Shepard growled menacingly whenever anyone was near. Instead, she stood behind the door frame to hear what she could as Lala would never kill her but the hulking black and gray demon dog surely would. The teacher told Lala everything.

After she left, Lala came into the hot, narrow kitchen where Alma was pretending to stir the frijoles. She approached without a word and slapped Alma across the face. That afternoon, Eduardo’s family pulled him out of school and sent him to work on his abuelo’s finca in Las Villas. Alma made a deal with the Virgin; if the sainted mother would see to it that she’d be reunited with Eduardo, she promised to say seven extra Hail Marys every night and name her first daughter Reglita, dedicating her to Yemayá.

To bring in some extra money, Alma took to mending things for the roomers. Sometimes, while she was fixing something or sewing on a button, Lala would tell her stories from the past.

“Can you even imagine how poor we were when all the men died?” Tía’s grandfather, father and uncles, including Mamá’s father, had all died in the last revolution, when Cuba was liberated from España. “Your aunt Orfa was a lot older than me . . . She and I were little girls and our mamá was alone so she asked all three sisters-in-law to come stay here. Our house was brand new then, the only one on this hill,” Lala gestured to the left, to the right, then left again. “There was nothing here, can you imagine it? Abuelo had come to live here after Abuelita Victorina died. Papá provided, thanks to God and our virgencita de Regla.” Alma knew that he had worked at the port, though she wasn’t sure exactly what he did but that it was a job with enough income for a house full of females after the war, when there wasn’t anyone else to provide enough of anything.

“Porbrecita Mima, she tried her best to feed us all but after the men were dead and buried, the sisters-in-law returned to their own families. We never heard from them up to this day.” Lala didn’t dwell on the betrayal her mother felt in favor of drawing out the description of their poverty. “Do you know what piltrafa is?” Lala widened her bloodshot eyes as she asked.

“I can’t remember, tía.” Alma said, feigning ignorance, hoping for new details. “Something like a soup?”

“Ha! If only it were even half of a soup like you know today.” Lala scratched her double chin. “As much as Mima insisted it was soup, I never thought it was because I remembered the tremendous soups she used to make before with lots of meat chunks in it and special thin noodles. For the piltrafa, Mima would walk all the way to the mercado over by the big traffic circle, where la Virgen of the Way’s statue sits, us girls walking alongside her. Niña, you know how far that is, right?”

Alma nodded in silence, her eyes focused on a button hole she was meticulously repairing.

“Mima would go to the meat market twice a week. Ay, Orfa and I hated the smell and all the flies but there wasn’t a living soul who Mima trusted with ‘confianza’ to watch us, especially the roomers she had started to take in. Why, they looked as poor as we were! So off we went every few days—with no icebox, what more could you expect? Mima would ask the butcher for the scraps left over from the beef cuts. Only a few people could afford beefsteak then, even worse than now. Do you know what I’m talking about, niña?”

Alma wasn’t sure if she meant the scraps or the people who brought steak. Before she could ask, Lala continued.

“The white strips of tendon and muscle. That’s piltrafa and it was usually for the rich people’s dogs or poor people like us. Mima would get the little piece of pork she could afford and there was one butcher who knew she was a widow alone with two niñitas so he’d save her some scraps that still had a little meat for her. Do you believe it?”

Alma didn’t have to answer because Lala had closed her eyes, signaling the end of the storytelling. Alma could fill in the rest, how the scraps would be put into a big pot of boiling water to get the flavor of meat so that any viands they had would taste more than the tasteless, starchy tubers they were; how that was what sustained them. That and their prayers to Our Lady, of course.

Her little mending jobs gave Alma some extra money to buy discounted material to sew herself a new dress from time to time. No longer flat-chested, her brown nipples were the yokes of what Lala called “two fried eggs.” Eduardo would have liked to have tasted these, Alma thought, remembering the latest letter he’d sent. Alma had started receiving the crumpled letters that his older sister Olga handed to her in grammar class at the Escuela Superior.

That first letter began with “If this letter reaches you, mi querida, know that I love you and only want to be with you day and night, especially in the night.” This line made Alma tremble in a way only Eduardo’s touch had previously accomplished. He told her about the countryside near Camajuaní, how there were royal palms everywhere, how rich the soil and green the plants were. He said that there were so many birds he never knew existed and they sang songs every morning and even in the night that made his head spin but that nothing, darling Alma, was “as beautiful as the look you give just before a kiss.”

His abuelo, he wrote, like most guarijos, left the bohio early each day for the cane fields and returned after dusk. He didn’t want this for his grandson, so he had made a plot of tobacco Eduardo’s responsibility. In large loopy script, Eduardo described how much trouble it took to get the seedlings to grow into long luscious leaves ready for the drying shed. He said the leaves smelled sweet and that they were just as good as those grown in Pinar del Río where everyone said most of the island’s best tabaco was cultivated. His abuelo rolled his own cigars and sold the rest of the crop for cheap to neighbors or friends in the nearby pueblos like Taguayabón and as far as the small city of Remedios where he learned that they had the best Christmas carnavales. With pride, Eduardo told Alma that he got to keep a percentage of the tobacco profits and that he was saving money to come get her.

Alma considered a sacrifice to Yemayá, in order to prove her dedication to Eduardo. A whole watermelon, the goddess’ favorite fruit, to pray over and drop into the high tide at the malecón. She took to carrying seven copper coins in her pocket, using them as a rosary for Our Lady, passing each from pocket to pocket once the Hail Mary was completed.

One day, tía Lala said she needed to speak with her on a serious matter and led her into the sitting room. It felt strange to Alma being there because she couldn’t remember the last time they’d used the room.

Lala arranged her large loose hips in a finely carved armchair she said had been her grandmother’s and asked loudly why Alma’s hand in marriage hadn’t been promised by now.

“Hurry up and find a man, Pelucita. But a good, honorable man. I don’t want any no-count machos around here, especially the kinds that would have you run away from her family. A decent, hardworking man is what I want for you, Pelucita.”

Alma wondered if tía would ever give Eduardo the chance to prove himself. She looked above and beyond Lala’s agitated head to the framed saints in the bedroom.

“First thing I will do is send everyone . . .” this she said more quietly as she pointed upstairs, “packing! Solavaya todo el mundo! You and your husband would have the whole upstairs so you could make lots of children to fill those rooms.” She laughed a little, then looked away. “You know, niña, I’m not getting any younger.”

Alma saw the vision Lala had for her: selfless caretaker cleaning up after her aged great aunt and attending to the anticipated brood for the rest of her life, nothing but the same, cruel routine of old lady sicknesses or baby diarrhea, never seeing anything beyond the outskirts of Havana. (Lala wasn’t expecting Ricardo to take care of her; he’d joined the navy as soon as he could and was now sending home giddy postcards from New Orleans or Alabama and recently Key West where he was stuck for months awaiting his ship’s repair but never once, ever, did he send any money.) Alma’s throat constricted and her chest followed suit. It was as if her blood had slowed to molasses.