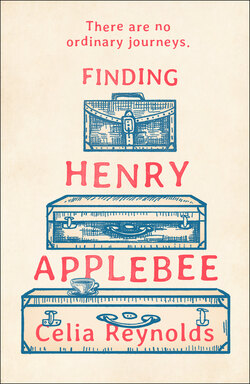

Читать книгу Finding Henry Applebee - Celia Reynolds - Страница 9

Оглавление1

The Notebook

KENTISH TOWN, LONDON, DECEMBER 5: JOURNEY EVE

Henry

My name is Henry Arthur Applebee. I’m eighty-five and counting, with an arthritic knee, a healthy head of hair and all my faculties, though not all my own teeth. I’ve had a pretty good life, but I’d be lying if I said I didn’t have any regrets. Anyone who gets to my age and says they have no regrets is either deluded, or senile, or both. When all’s said and done, the facts remain as follows:

I may be old, but it doesn’t mean I don’t still have any dreams.

Who’s to say there’s an expiry date on achieving your goals?

Is it ever too late to right a wrong?

Now that Devlin’s gone, I’ve learned that establishing a focused and precise daily mantra can be a very effective way of ensuring your marbles are still intact. ‘Stay engaged in life!’ – that’s what they say when you retire. Then, as time hurtles by and everyone you know starts dropping around you like flies, it’s: ‘Keep your mind active. Cultivate a hobby. Join a community group!’

But for me, it all comes down to my notebook. The Revealer of Secrets. The Holder of Truths. The place where those I’ve loved reach out – right from between these very pages – and, grinning, take me by the hand and say, ‘Come in! Don’t be shy. You want us to show you something marvellous?’

It began, somewhat prosaically, with Adam Donnelly, a young man from Wyedean who called in to see me at the start of July. Banjo and I had been managing just fine on our own up until then. But visitors have an annoying knack of stirring things up; of reminding you there’s a whole sprawling world beyond the confines of the one you’ve learned to inhabit by yourself.

‘We’d like you to write an article for the Wyedean quarterly magazine,’ Adam D. said. ‘It’s for a retrospective we’re running on former members of the teaching faculty, and as our most senior contributor, we’ll be featuring you in our cover story. You’ll be the poster boy for excellence! For a life well and truly lived.’

A small weight snowballed inside me. ‘Will anyone still be interested?’ I asked. This was not false modesty; on the contrary, I was positively taken aback. The corners of Adam D.’s mouth veered upwards. ‘You’re one of Wyedean’s most esteemed former language teachers, Mr Applebee. The board thinks a self-penned profile will be illuminating not just for the current staff and pupils, but also for your peers.’ ‘Oh,’ I said, ‘I see. Are any of them still alive?’

I hadn’t heard from Wyedean in a long while and the request puzzled me. ‘What kind of illuminations are you looking for?’ I asked. ‘Anything uplifting,’ he replied. ‘Anecdotes, observations, greatest achievements. That kind of thing. It’s a tough world our pupils are facing. Hugely competitive. Our aim is to buoy them up with as much support and inspiration as we can.’ Adam Doolally drummed his fingers on the arm of my wing-back chair and smiled encouragingly once again.

Doubtful as to my ability to either illuminate or inspire, I nodded. Signed on the dotted line, as they say. It was only after he’d gone that the full magnitude of the task hit me: academic career aside, I couldn’t think of a single event in my life which might reasonably qualify as a ‘greatest achievement’. Nothing worthy of the inspiration-hungry readers of the Wyedean quarterly magazine, at any rate.

How in the name of all that’s holy does a senior citizen, occasional UFO spotter and Francophile reduce eight-and-a-half decades (and counting) of life to a fifteen-hundred-word article? It felt remarkably as though I were being called to account. ‘Impress us!’ Wyedean seemed to be saying. ‘Tell us what you know. What you’ve learned. Show us who you are.’

Bells of panic filled my chest. (Never a good sign at my age.) What Wyedean wanted was insights, the Happy Ever After. But what about the areas of my life where I’d failed so spectacularly? What on earth was I supposed to say about those?

I decided to narrow my focus and stick to the long, seamlessly interchangeable years spent teaching hormonally fuelled adolescents to conjugate French verbs. It was quite staggering, when I came to think about it. Entire decades had slipped by. Decades filled with page after page of Verlaine, Gide, Maupassant, Baudelaire. It was extraordinary, the degree to which I’d buried myself in those pages. Revelled in their majesty. Wallowed – privately – in their pain.

To Wyedean, I was still Mr Applebee: devoted (and, it would seem, fondly remembered!) former Head of French; but to me I was just Henry, the gauche, skinny teenager running around the streets of Chalk Farm with Devlin, yet to put on the uniform, yet to meet the girl.

When the article was finished, I dropped it, shamefaced, into the post box and tried desperately not to think of it as a lie. An evasion, maybe, but then how could they know it was the things I didn’t put in – the personal things, the things buried at the bottom of a dusty suitcase – which had defined me?

Changi… Sunburn so bad the skin peeled away from my chest in sheets. Everyone told me to keep quiet about that. It was a punishable offence. The officers would scrub the blisters with salt water if they got wind of it. I grew up so fast, I barely recognised myself when I arrived back home.

And then, when I did so, I climbed a staircase and there she was. The very last thing I was ever expecting to happen to me, Fra–

Henry’s hand jerked abruptly from the page. A noise (a grunt? A cough? A chuckle?) filtered through the wall from the spare room.

‘Devlin?’ he whispered. ‘Devlin, is that you?’

Henry cocked his good ear to one side, but all he could make out was the steady ticktock ticktock of the carriage clock on the mantelpiece. He held his breath, the curvature of his spine straightening by degrees until finally, he felt it: his brother’s voice, brushing like dew against his skin.

Evening, Henry. How’re things?

Henry wiggled his finger in his ear. Devlin. Where does one begin to capture the essence of a man whose character had been so large, so utterly irrepressible that even in death his exuberance couldn’t be contained?

Don’t keep me guessing, Devlin continued. How’s tricks? What’s going on?

Henry settled back into his chair and attuned himself to the frequency, as though he’d stumbled across some strange, transcontinental broadcast on the radio. ‘I’m fine,’ he replied to the room at large. ‘Fine, that is, aside from the fact I’m sitting here, in my living room, talking to you.’

He stared into the flat, empty space ahead of him and beamed.

Following up his Wyedean article with a notebook of ‘recollections’ (memoirs seemed too worthy a concept, too weighty, too proud) had been the result of an overwhelming urge to continue writing, only this time Henry was determined to do it for himself alone – no expectations, no limitations, no holds barred. What he hadn’t bargained on was the way the focused bursts of concentrated silence gave rise to many strange and wonderful occurrences, not least of all these fleeting, otherworldly conversations with Devlin, two years gone.

Occasionally, like today, Henry answered him out loud, but he didn’t like to make a habit of it in case he forgot himself and did it in public. Next thing you knew, if anyone saw him chuckling or talking to his dead brother while he was queuing for his pension at the post office, they’d be carting him off to the funny farm.

‘I’m going away,’ Henry ventured with a faint whiff of heroism. ‘And the truth is, I don’t think I’ve ever felt so simultaneously terrified and exhilarated at the prospect of anything in my entire life. I leave for Scotland tomorrow morning on the nine o’clock train.’

He lowered his gaze. Deep inside his chest, his heart began to quiver.

Away? Devlin’s voice, bolder now, slipped a little further beneath Henry’s skin. It’s her, isn’t it? The girl? Don’t tell me you’ve actually gone and found her after all this time?

Henry bristled. ‘She has a name, Devlin. And as to finding her, yes, it would seem to be the case.’

There was a momentary pause.

Hellfire. So what’s the problem?

Henry shifted in his seat. ‘Well – if you must know – I’ve had a premonition. But I won’t be stopped,’ he added in a tremulous voice. ‘Not by you. Not by anyone.’

Have you finally gone loco? Devlin shot back. When have I ever discouraged you from doing anything? The way I remember it, it was always you who’d be running after me! Ah Jesus, Hen, what’s with the premonition, anyway? I leave you alone for two minutes and you’re moonlighting as some kind of oracle? Sounds to me like someone’s got way too much free time on their hands!

There was another brief pause. Well go on. Let’s have it then.

Just the tiniest bit miffed, Henry cleared his throat. ‘That despite all my hopes and prayers for the contrary, nothing at all is going to go to plan.’

He sucked in his cheeks and waited for Devlin’s disembodied response. When it didn’t come he shook his head, waited, shook it again, but the signal – for want of a better word – was gone.

Alone once again, Henry slipped off his tortoiseshell glasses, rubbed his eyes with the heels of his hands and rose stiffly from his chair. He carried his notebook into his bedroom and placed it next to a jar of Vicks VapoRub on the bedside table. Banjo, his Parson Russell Terrier, padded into the room behind him and hovered at his side, his ears drawn back, his face full of mistrust.

‘Banjo, come on now, get out from under my feet,’ Henry said gently.

On the eiderdown, his small brown suitcase lay open and ready, the air around it lightly tinged with must. A faint tremor rippled upwards from Henry’s fingertips as he stepped towards it, and with painstaking care and attention proceeded to remove a series of bundles from the elasticated pocket running along its side:

1 1. a silver hair-slide, a pearl and diamanté butterfly perched on its tip, wings spread;

2 2. a uniform cap, field service, blue-grey;

3 3. a paper napkin the colour of turned cream, bearing the faintest imprint of coral lipstick;

4 4. a picture postcard, the back of which was filled with a seemingly random miscellany of words and phrases, each forward-sloping letter jostling against its neighbour like links in a tightly woven chain;

5 5. a jagged strip of dark red velour.

Henry unwrapped each item individually and turned it over in his hand. Raising his gaze, he cast a surreptitious glance at the alarm clock by his bed.

Twelve hours exactly to departure.

One memory at a time, Henry placed his past back in his case. His preparations complete, he made his way back to the living room and lowered himself into his wing-back chair with a cup of Ceylon Orange Pekoe and three custard creams.

‘Amended Mantra of the Day,’ he said, turning to Banjo’s upturned face. ‘No matter what age we reach, or however much our lives may settle beneath the inevitable cloak of familiarity, it is never, ever too late to be amazed.’

Henry wondered what the people from Wyedean would say if they knew the context behind his words. That he was a fool, probably. That after a lifetime of so-called academic excellence, how banal, how unoriginal of him to admit that what mattered to him most now was love.

He shifted his gaze to the antiquated furniture and mountains of yellowing books as though viewing everything for the first, or last, time. He would not return. The world could mock him all it liked, he wouldn’t give up until he’d said the words he needed to say to the only person alive who mattered to him now.

Henry’s hand drifted to an envelope peeking out from his cardigan pocket. Inside it: pre-purchased train tickets for Edinburgh. First Class. Two.

‘Perhaps it’ll be fine after all,’ he said, his spirits revived by a resurgent ray of optimism. He leaned over and rubbed the back of Banjo’s head. ‘And if it’s not fine, then stone me, at least it’ll be illuminating…’