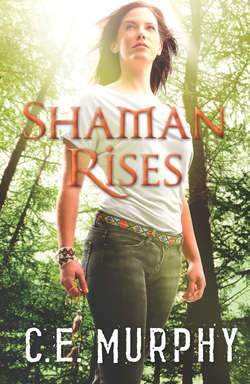

Читать книгу Shaman Rises - C.E. Murphy - Страница 9

ОглавлениеChapter One

Friday, March 31, 11:29 p.m.

Annie Marie Muldoon was supposed to be dead.

She had been dead the whole fifteen months I’d known her husband, and she’d been dead the three years previous to that, too. That had been pretty much literally the first thing I’d learned about Gary Muldoon: his wife had died of emphysema on their forty-eighth wedding anniversary, so no, he didn’t have a cigarette for me to bum. He’d told me a lot about her in the past year and some: how she’d been a nurse, how she had been the breadwinner in their home for much of their marriage, how they’d traveled the world and how she had been a bright and gentle spirit. Everything he’d said had made me wish I could have met her.

Nothing he’d said had prepared me for the possibility I might. Not even the shamanic magic I’d finally mastered led me to believe it was possible. I did not, as a rule, see ghosts or talk to dead people.

I was, however, perfectly capable of seeing and talking to people lying in hospital beds, which is where Annie Muldoon was, and where, according to her records, she had been for the past four days. The doctors were embarrassed about that, because according to their other records, she was dead, and somebody had clearly made a horrible mistake. Doctors weren’t renowned for their apologies, but every time I’d spoken to one in the past couple hours, he or she had apologized to me, and I wasn’t even technically a family member.

Gary, though, had made it pretty damned clear to them that they not only could, but should, be talking to me. He’d accepted every strange leap and twist of my life with equanimity, but this one had taken him in the teeth. He sat hunched and haggard at Annie’s bedside, looking every one of his seventy-four years for the first time since I’d known him. He’d gotten up to hug me when I’d arrived. Other than that, he’d been sitting with Annie, holding her hand and watching her breathe.

She was a tiny woman, made smaller by sickness. The apologetic doctors had already told me six or eight times that she had emphysema, just like the older records showed, and...and then they faltered into silence. None of them had an explanation for her recorded death. None of them had any idea where she’d been in the intervening four and a half years. None of them were in fact entirely clear on how she’d shown up not just at the hospital, but in a bed, in a private room, and they sure as hell didn’t understand how a dead woman’s insurance policy was still active. That, of all things, was going to be the most trouble later. I didn’t want Gary getting in trouble for insurance fraud.

The rest of it, I could explain.

Friday, March 31, 8:30 a.m.

“Jo,” Gary had said on the phone, “I’m in Seattle. It’s my wife, Joanie. It’s Annie. She’s alive.” And my appetite vanished.

It should have vanished, of course, because I’d just eaten about eleven metric tons of food at Lenny’s, the diner in Cherokee Town, North Carolina, that I’d loved as a teen and still thought highly of as an adult. But this was the bad kind of vanishing appetite. It wasn’t sated. It was sick, my stomach suddenly in a hurry to reject every bite I’d just indulged in. I said, “But you were in Ireland,” through a rushing sound in my ears, and only half heard Gary saying something about the hospital having called him two days ago and now he was home and Annie was alive.

I got up from the table, leaving my breakfast date, Captain Michael Morrison of the Seattle Police Department, to either pay the bill or skip out on the check. It wasn’t that I didn’t plan to pay. I just wasn’t thinking that clearly as I went out into the cool Appalachian morning. “Gary. Gary, start again. Say that again. Annie—Annie...”

I didn’t want to disbelieve him. I didn’t want to say the words out loud: Annie died five years ago, Gary. My life was too damned weird to brush him off entirely, but coming back from the dead five years later was way beyond my ordinary level of weird.

Gary’s voice shook. “Jo, I ain’t told you the half of what happened with me when I went riding with Cernunnos.”

“...tell me.” I got myself across the diner’s parking lot and sat on the hood of the Chevy Impala I’d rented to drive around Cherokee in. I pulled my knees up, wrapped an arm around them and put my head against them, like I could protect myself from all hell breaking loose if I curled into a small enough ball. “Okay, Gary, tell me what’s going on.”

“I went ridin’ off with Horns to fight in Brigid’s war, and—” My old buddy caught his breath and I could all but hear him editing the story down to the bare bones. “An’ I caught the Master’s attention, Jo. The rest of it don’t matter right now, but he saw me. He looked right inta me, Joanie, an’ he promised he was gonna take away everything I loved. He promised he was gonna take Annie away, Jo.”

I closed my eyes hard. Gary and I had gone to Ireland together so I could hunt down the source of visions I’d been having, but a funny thing had happened on the way to the forum. My magic had thrown us into Ireland’s distant past, where I’d had to prove myself as a shaman by summoning a god. I’d called on Cernunnos, god of the Wild Hunt, who was itching for a fight with our common enemy, a death magic we called the Master. I’d had other things to deal with just then, and Gary had volunteered to join Cernunnos in that battle. I hadn’t seen him again until he rode up and stuffed a sword through the banshee queen who was trying to kill me.

I’d thought that was it. He hadn’t suggested there was anything else to the story. Of course, in the twelve or fifteen hours immediately after our Irish adventures had ended, I’d been alternating between sleeping, eating and trying to help my cousin Caitríona get her feet under herself as the new Irish Mage. Then a friend had called me from North Carolina and told me my father was missing, and I’d been on the next plane to America. There had not, frankly, been much time for catching up.

Apparently I’d missed a lot. I caught pieces of the story now, stitching Gary’s fear and confusion into something coherent only because he repeated bits often enough that I was able to build a time line. He had asked, no, demanded that Cernunnos take him into his own past so he could protect Annie from the Master’s meddling. But we’d all learned the hard way that time travel didn’t work that smoothly. The time line wanted to stay the way it was, without interference. One change in an era meant nothing else could be changed. Cernunnos had warned Gary not to make a move until the last possible minute. So he hadn’t, and somewhere along the way he’d forgotten things, forgotten about killing the demon in Korea, forgotten about—

“Wait, wait, what? You killed a demon in Korea, Gary? What the hell, that was fifty years ago and you, dude, Gary, you didn’t know anything about magic when I met you.”

“That’s what I’m tellin’ you, Jo, he took it away. This whole damned life I led, this life me an’ Annie led. I’m remembering it all now, like somebody’s scrubbin’ away the fog. He tried killin’ her half a dozen times in half a dozen ways, Joanie, an’ in the end he got a black magic inside her to eat up her lungs. You remember Hester Jones?”

I sat up straight, blood draining from my face. To my surprise, Morrison was a few feet away, leaning on a different car’s hood, arms folded across his chest as he waited to be there when I needed him. My chest filled with gratitude and I managed a wan smile, but I was mostly thinking about Hester Jones.

I’d never known her when she was alive. She was one of half a dozen Seattle shamans who had died a few days before my own power had awakened. She and they had pooled their resources so they could remain in the Dead Zone, a place of transition between life and death, long enough to set me on the path I needed to be on. Hester had had a sour-apples voice and a permanently pinched mouth. I remembered her very clearly, and nodded like Gary could see it.

“She tried helpin’ Annie, but it didn’t work. Not mostly. She found Annie a couple spirit animals, though—”

I was on my feet again somehow, looking past Morrison toward the blue mountains. “What animals? Morrison, can you go get my dad? Or Aidan? Both? Now?”

Morrison, bless him, pushed away from the car he’d been leaning on and headed into the diner without asking any questions. Gary was still saying, “A stag an’ a cheetah. She kept sayin’ how silly a cheetah was, like that was a young girl’s spirit animal, not an old lady’s,” when Aidan, the son I’d given up for adoption almost thirteen years earlier, came running out of the diner. His mother Ada followed him, and Morrison, now on his phone, came out after them.

Aidan skidded to a stop in front of me, cheeks flushed with excitement. He’d had a hell of a few days. His once-black hair was bone-white and even more shocking in sunlight than it had been in the diner. “What’s going on? What do you need? Are you okay?”

“Information on spirit animals. What do cheetahs and stags represent? What gifts do they offer the people they come to?”

“Stags are strength and virility—” He blushed saying the second word and cast a sideways glance back at his mom, who studiously didn’t notice. Still blushing, he shoved his hands in his pockets and mumbled, “Um, those are the ones I know about mostly. Cheetahs, I don’t know about cheetahs, they’re—”

“Time.” Morrison’s voice sounded unusually deep compared to Aidan’s boyish soprano. “Your dad’s saying that cheetahs offer gifts of speed and time. Not the way your walking stick spirit animals do, he says, but—” He broke off, tilted the phone away from his head to look at it slightly incredulously, then lifted his eyebrows and went on. “Did you know, he says, that cheetahs are one of a few cat breeds that can’t retract their claws, and can’t you see how that gives them the grip to pull someone—”

“—past when she died, Jo,” Gary was saying in my other ear. “She died at 11:53, seven minutes to midnight, doll, I know that right down in my bones, ’cept she didn’t. I’m rememberin’ it different now, rememberin’ how she held on, Jo. She held on until midnight, an’ Cernunnos... I dunno, Joanie. He came outta the light and she put her hands out to him and...an’ that was it. Next thing I knew I was back with the Hunt and I couldn’t remember my whole life right, and we were headin’ back for you. It all didn’t start comin’ back to me until the hospital called and said Annie was...there.”

“How is she?”

“Dying.”

The blunt word hit me like a red dodgeball, smack in the gut. Breath rushed out of me, though I should’ve known that “dying” was the only really possible answer. “How long does she have?”

“They got her on life support, Jo. She ain’t awake. They don’t know if she’s ever gonna wake up an’ they ain’t sure she should. Sounds like they think the only thing keepin’ her alive is that she’s sleepin’.”

“I’ll be there as soon as I can. Hang in there, Gary. I love you.”

There was a startled silence on the other end of the line before Gary’s voice came across one more time, gruff with worry and pleasure. “Love you, too, doll.”

We both hung up. Aidan peered between me, Morrison and my phone, which was fair enough. Five minutes earlier Morrison and I had been being, in Aidan’s assessment, mooshy and gross, and now I was saying “I love you” to men named Gary. I decided to let the kid work that one out on his own, and looked at Morrison.

He handed me his phone. I took it, catching the scent of Old Spice cologne clinging to it, and smiled as I said, “Yeah, Dad, thanks for the help. Um, look, I know I said I was going to hang around, but something’s come up. I gotta go back to Seattle, like now.”

Aidan said, “But—!” and his mother put her hand on his shoulder, which slumped. I made an apologetic face at him and spoke to him and my dad both. “It’s my best friend. His wife is...sick.” Back from the dead was more than I wanted to try explaining, since I barely comprehended that myself. “I’m not even sure I should waste the time driving home. I think I need to fly.”

“Are you willing to leave Petite behind?” Morrison asked.

I snorted, then realized he was serious. “No, what, are you kidding? I thought you’d—I mean, you drove her out here...”

“Walker, do you really think there’s any chance I’m letting you go back to Seattle to help Annie Muldoon without me at your side?”

A rush of embarrassed, delighted, teenage-intense emotion rushed through me and turned my face hot. I wasn’t used to the idea that somebody, anybody, much less a silvering fox like Morrison, wanted to be at my side. And now that he made me think of it, he was the only other person in the immediate vicinity who understood just how alarming it was that Gary’s wife was merely sick. “I guess, I mean, no, when you put it that way....”

“That’s what I thought. So either we’re both flying or we’re both driving.”

“I can’t...drive fast enough. I mean, the record for driving across the States is about thirty hours, and we’ve got most of that distance to cover.”

Morrison flicked an eyebrow again at the fact I knew what the cross-country driving record was, but he didn’t comment on that. He said something far more astonishing instead. “I can call in some favors and get the roads cleared, get us a police escort across the country. How fast can you do it then?”

My jaw dropped. I closed it again, wet my lips, and felt my jaw fall open again. “You have never been as sexy as you are right now.” Aidan, hearing that, looked mortified while I kept gazing in stunned lust at Morrison. “You would do that? What excuse would you use?”

“That I had a critical case and couldn’t fly, which happens to be true. How fast could you make the drive?”

“About...” I closed my eyes, envisioning the route, the roads, and Petite’s top speed before slumping. “Even if I could keep her pegged, which is unlikely, it’d take most of a day, and I haven’t slept since...” I didn’t know when. Drooping, I tried to rub a hand across my eyes. There was a phone in it, which made me realize I hadn’t actually ended the conversation with Dad. I put the phone back to my ear and said, “Did you go get Petite?” and got an affirmative grunt in response. “Okay. I need you to drive her to Seattle.”

Morrison’s eyebrows shot skyward while I tried not to think too hard about what I was asking. Dad had already driven my beloved 1969 Mustang down the mountain to his house, which under ordinary circumstances would be grounds for kneecapping. I did not let other people drive Petite. Except Morrison had driven her all the way from Seattle to bring her—and himself—to me in a moment of need, and now I was telling Dad to haul her big beautiful wide back end across the country again. I could take it as a sign of maturity and of letting go, but really it was more a sign of desperation.

“You, ah. What?” Dad sounded as shocked as Morrison looked, but possibly for different reasons. “You need me to what?”

“Drive my car to Seattle, Dad. You know the road.” A thread of humor washed through that. My father and I had driven all over the country in my childhood. The idea that he might not know the way—which was not at all why he was asking—amused me. Any port in a storm, I guessed.

Dad’s silence spoke volumes. Up until about twelve hours ago, we hadn’t talked to one another, much less seen each other, in years. My doing, because I’d been on a high horse it had eventually turned out I had no business on. We had only just barely buried the hatchet, though, and it was a big thing to ask. A three-thousand-mile thing to ask, in fact. I was trying to figure out another course of action when Dad cleared his throat. “How soon do you need her there?”

My knees went wobbly with relief. “As soon as possible.”

“I’ll pack a bag and leave from here.”

“Thank you. Thank you, Daddy.” I mashed my lips together. I hadn’t called my father “Daddy” in well over a decade. It was, in my estimation, kind of a low blow.

A breath rushed out of him loud enough to be heard over the phone, and I decided it wasn’t as low a blow as it would have been if I’d Daddy’d him in the asking. He said, “See you in Seattle, sweetheart,” and hung up.

I folded the phone closed and handed it back to Morrison. “I got the Impala at the Atlanta airport. We can drop it off when we—crap. My credit card is maxed out.” I shot a guilty glance into the Impala, where lay a gleaming new ankle-length white leather coat. “I have no money for a last-minute plane ticket. Maybe I better drive after all.” I reached for Morrison’s phone to call my father back, but he put it in his pocket.

“I got this one, Walker.”

Part of me wanted to protest. The much smarter part smiled gratefully and whispered, “Thanks.”

Morrison nodded while Aidan went to see what it was that had broken my credit card. He dragged the coat out and knocked my drum, which was under it, onto the floor of the car, which made him say a word I imagined his mother liked to pretend he didn’t know. After putting the drum back carefully, he held the coat up to me, then made me put it on over my protest of, “You’ve seen me in it already, Aidan....”

I received a glare worthy of the fiercest fashionista, even if he was a few weeks shy of thirteen years old. Still glaring he studied me, twirled a finger to make me spin and finally gave me a peculiarly familiar smile when I faced him again. “That’s an awesome coat. You look like an action hero.”

I struck the best heroic pose I could manage, chin up, arms akimbo, gaze bright on the horizon. Aidan laughed, but I’d bought the coat in part because it really did make me feel like a hero, like I was wearing a white hat that proclaimed me as one of the good guys. It was a nice feeling, and I wasn’t too concerned with the thought that it also made me a target. I’d done a fine job of becoming a target without the coat’s assistance, so I figured I might as well enjoy it if I could.

When I shook off my silly pose, Ada and Morrison had moved away, leaving Aidan still grinning at me without noticing we’d been given some space. I flicked a fingertip at his white hair. “If this stays like that, you won’t need a white coat to look like a good guy.”

He rolled his eyes scornfully. “You don’t watch enough movies. Anybody with totally white hair is always the bad guy.”

“Oh. Jeez, you’re right. Okay, you’re just going to have to buck the trend. Look, Aidan, I’m sorry I’ve got to go. I really did want to hang around a few days.”

His mouth twisted, disappointment not quite strong enough to make him defensive. We weren’t that close, which was okay, and besides, he got to the crux of the matter, focusing on what was important. “Is it a shaman thing? Is that why you’ve gotta go?”

“Yeah. My best friend’s wife is sick, really sick, and...” I swallowed, because I didn’t at all want to pursue my thoughts to their logical end. “And I have to try to help.”

“We can’t always.” The kid was solemn enough to be five times his actual age. “You know that, right? Not everything can be healed.”

“But sometimes they can be fought,” I said quietly. “Sometimes putting up the fight is what matters. But I guess you know that. Especially after the last couple days.”

Aidan shifted uncomfortably. “You did most of the fighting. I just...was awful.”

“You were possessed, and you didn’t give in to it, Aidan. That’s what matters. You held out so I could fight for you.”

“A lot of people still got hurt.”

“Yeah, and I know it’s not going to be easy for you to accept that none of that was your fault. You and I were both targets, and the thing that came after us loves collateral damage.”

“How’re we supposed to make that better?”

I looked west, like I could see all the way to Seattle. “That’s what I’m going home to do, kiddo. I’m gonna make it better. I’m going to finish it.”