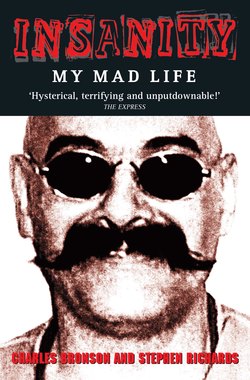

Читать книгу Insanity - My Mad Life - Charles Bronson - Страница 5

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

INTRODUCTION

ОглавлениеBY STEPHEN RICHARDS

Charles Bronson! Two words that conjure up conflicting thoughts: One — is he the great American Death Wish actor? Two — Oh, yeah, I know who he is, he’s that madman in prison who keeps taking hostages … I think. In this case, we’re talking about Charles Bronson, the man dubbed the UK’s hardest man, the man labelled the UK’s maddest and baddest hostage-taker, self-confessed ‘King of the Roofs’ and one of the kindest men you could ever meet!

There are three sides to this man Bronson — good, mad and bloody bad, the good side very rarely being revealed to the person who has experienced the mad and the bloody bad sides. The mad and bad parts of Bronson’s persona are usually held in reserve for those on the same side of the prison wall he’s behind, particularly paedophiles and bully screws.

The able and willing part of Bronson’s persona is generously bestowed upon those who have earned his kindness. As if some king giving his grateful subjects a royal wave, as if the Pope giving his papal blessing, as if a great wizard casting a lucky spell for his willing students, Bronson can equally give his heart and soul for those he believes in. But there is also a warning label attached to the Bronson kindness — ‘Handle with care, treat with respect or you’ll regret it!’

When you breed man-eating piranhas, they say you haven’t been a successful breeder until you’ve been bitten by one of the killer fish. Piranhas don’t actually bite as such — they scoop out the flesh of their victim, leaving a big messy hole! Once you’ve been blooded, then, and only then, have you received your rite of passage and you can declare yourself to be a successful breeder, displaying the healed wound as proudly as a newly promoted Hell’s Angel shows off his newly won patches.

Very few people are able to say they have endured the wrath of Bronson after a close friendship and then, afterwards, were able to start all over again with the man. I, Steve Richards, have had that dubious honour.

Charlie Bronson and I have fallen in and out of friendship more times than I care to remember. I’ve been blooded and obtained my patches the hard way — Charlie respects me for my stance. Once, writing to the big man, I mentioned a particular subject that I was disgruntled about: ‘I want you to bend over, 90 degrees, from the waist, take the document and ram it up your arse.’

Charlie sent the letter to one of his then close supporters and had written over the top of it, ‘He’s either mad or very brave!’

Our little fall-out lasted for quite a while. He’d write to me in a nasty and sarcastic, but funny, manner and I’d respond with an equally caustic reply — childish, really!

During the course of our love–hate relationship employing angry words, one thing became apparent — Charlie was able to express his anger by proxy. He wasn’t able to pin me down and punch my lights out; he had to express his anger by letter. He dared, I thought to myself, to cross swords with the Golden Pen, a name given to me by some of the criminal fraternity. The man I was fighting was able to give as good as he got; as a consequence, both of us suffered the damage of our ever more daring penmanship and, I can tell you, he gave a good fight and became a great, great friend of mine, a friendship that I would not wish to lose.

I am the sole survivor of similar disagreements that he has had with those who have supposed him to be unable to comprehend what goes on in the outside world. I believe this special bond I have with Charlie gives me the authority to be able to speak so expertly about him.

Not once did I blame Charlie for his actions; always, instead, I blamed the penal system for what they had done to him. After reading this book, I’m sure you, too, will also blame the system for its mismanagement of one of its most misunderstood inmates.

During the course of being honoured in assisting Charlie with his work, I banished myself into solitary in order to experience what he must feel like and to get a better understanding of how it can make or break you as a person. Obviously, I couldn’t endure the 24 years he’s suffered in such solitary conditions, but what I was able to do was divest myself of all the worldly goods we, outside solitary, take for granted.

First, it was away with my mobile phone, my precious cigars … oh, what the hell, they could go as well, as would my other daily luxuries. I even banished myself to a stark building with a steel door, locked from the outside, with no heating, no ventilation, no phones, no snacks, no newspapers … nothing! With just my pen and a notepad, I was beginning to know what solitary felt like.

I did, however, grant myself two luxuries: One — soft toilet roll; Two — cans of Pepsi-Max. The Pepsi would help take away my craving for nicotine and now the fight was on. One hour into the venture I felt great — yeah, I can do this, no problem.

After a sleepless night on wooden pallets, stacked four high to represent Charlie’s sleeping conditions, I was wondering if what I’d embarked on was, as Charlie would put it, a mission of madness. The following morning saw me standing by the steel door like an expectant dog waiting for its master to return home … the door opened … light, real light!

I decided to take an hour off, equivalent to the one-hour exercise Charlie is allowed. What would I do in this hour? Sneak off, look for a newsagent and buy a pack of cigars? After all, I still had money in my pocket. Yes, no, yes, no, yes … so the inner battle went on. I walked up to the shop, went in and bought a tray of Mr Kipling’s Apple Pies. Was I that mad after only one day! If I’d bought the cigars, I’d have let Charlie down. OK, he wouldn’t have known, but in our new-found closeness it meant a lot to me not to lie to him, to keep the faith, bro’.

In the early stages of my captivity, I was like a giggling schoolboy on a mystery school outing … this was going to be an adventure after all! Washed down with the Pepsi, the apple pies tasted good. I soon forgot about the cigars I had craved, and then I found myself looking at stark reality! The magical mystery tour had turned into a sudden realisation that this might be madness.

I was sitting looking at the bricked ceiling, the plain-bricked wall and a closed steel door. It dawned on me … what if something happened, like if I developed appendicitis or I was to have a heart-attack or something equally life-threatening? At least if this happened to Charlie he could bring this to the attention of prison officers by pressing a call button in his cell. Hmmm, I thought.

The following day, I was supplied, at my request, with a new cheap throwaway mobile phone. New because it meant no one would be ringing me; it had £10 worth of credit on it. Charlie is allowed to make phone calls, which to date he refuses to do because of his fight to have open visits with his wife, Saira. The prison authorities will not allow Charlie any contact with visitors and all visits have been ordered to take place with Charlie behind a steel cell door, so, consequently, as a protest Charlie now refuses to make phone calls. I took up my entitlement to use £5 worth of calls in a seven-day period and that way, if need be, I could phone for help.

I felt a lot safer with the mobile phone, but what it did make me aware of was all of the times Charlie needed help and how he was refused access to a doctor, when he was left lying in a stinking cell trussed up in a restraining belt two sizes too small for him and with only a few cockroaches for friends. Nah, I wasn’t prepared to go to those lengths to see what Charlie must have been feeling or thinking … I’d use my imagination and, besides, the supplies of apple pies were running low!

Dinner had arrived … mmmmmm, aaaaaaah … the smell of fish and chips nearly brought me to my knees in appreciation. Hey, this wasn’t too bad after all … wasn’t I doing well, my second day in solitary? No sweat.

I had to sort Charlie’s handwritten notes into order so that would help while away the hours. Most people cannot read Charlie’s scrawled handwriting … me, I’ve got no problem. If I could read Reggie Kray’s almost impossible, hieroglyphic-style handwriting, then Charlie’s presented no problems. (After all, my scrawl is just as bad.) Time was flying! This made me aware that so long as Charlie was kept busy, then time would fly equally fast for him. I mean, after all, at least he had his art and his many hundreds of letters from fans to reply to. Yes, I had decided, that was the key to it all … keep busy.

Charlie has had his art materials taken from him countless times by the prison authorities as a punishment for minor and major breaches of prison rules. Charlie even went on hunger strike at HMP Whitemoor for a 40-day period when the prison confiscated his art materials, but by doing this they were ‘taking away his soul’, his reason for living, and now, after only two days, I was beginning to understand what he meant!

Charlie once punished me by withdrawing all his art from me. He wrote, ‘I’m not sending you any more art until January 2002 because you don’t appreciate my art.’ My misdemeanour was not to have sent him photographs showing his pictures hanging on my office walls! That’s how much he values his art works. Charlie actually sent me more drawings before the period of withdrawal had expired … he’s such a softy!

Teatime had arrived! I stood by the door with baited breath … what goodies could I expect? Nothing! What … nothing? Yes, nothing. I was supposed to be brought a meal three times a day, but the person responsible for this had been called away on urgent family business and it was passed on to someone else. Now isn’t that typical of what happens in Charlie’s life? Others are delegated a job and that’s when things go wrong — talking but not communicating.

So there I was, standing by the door arguing! The only thing I was handed was a list of urgent phone calls that had been left at the office for me! I blew my top. ‘For fuck’s sake, what am I supposed to live on until tomorrow morning?’ I said with an aggression that surprised me.

‘Hang on a minute …’ the person responded but, before they could say anything else, I apologised and said I didn’t know what had come over me. I explained that I wouldn’t be getting anything else until breakfast and needed my tea. Ten minutes later, I was brought a bag of crisps, a Mars bar and two cheese pasties … oh well, better than nothing, I suppose.

Again, I was now made to think of the times Charlie had told me over the phone about his meals being messed up. He told me that if he was expecting a visit, when he was allowed open visits, he wouldn’t have dinner because his visitor would be able to buy goodies from a vending machine in the visits room. But if the visitor didn’t turn up, he would be starving by the time his last meal of the day was served. I was beginning to understand what this cock-up would mean to a solitary prisoner. I was beginning to understand why such a small thing as a missed meal could set him off.

The solitary conditions brought me even closer to Charlie and here I was reading his handwritten notes that were now very relevant to my own condition. I could also understand why actors have to become the person they are playing; they go and study the person in great depth.

I noted among the list of phone messages I’d been given some time earlier that one call in particular was from Charlie’s wife, Saira. What was I to do? Break my code of silence and return her call? Would it matter if I did … after all, it was Charlie’s wife calling me?

No! I had to see it through; unless it was a life or death situation I would remain in solitary. Hey, hang on a minute, I thought to myself, Charlie has a radio in his cell … I want one, too! I hadn’t realised what interesting programmes there are on the radio; a great lifeline in such conditions, that radio became my friend.

Breaking point, I must admit, was near. Without a cigar, I was nearly climbing the walls, although at this stage I wasn’t chewing my nails, but I noticed that I had developed the habit of playing about with my eyebrows. By doing so, I was making them look rather curly, and when the steel door opened I was greeted with laughter. Not knowing what it was about, I didn’t find it funny, until it was pointed out what was making them laugh — my ‘Dennis Healey’ eyebrows; I, too, eventually saw the funny side.

This really was becoming insanity at its best! I imagined Charlie twiddling with his moustache, making the ends curly, as I had done with my eyebrows. A cigar, I’d love a cigar, I thought to myself. Charlie surely craved things as well; maybe it would be apple pies instead of cigars.

I had to make a brave decision. Nicorette patches were called for, one for each arm, I thought. No, maybe more to help me through, but the instructions said not to overdose by applying too many patches, so it was only the one patch to get me through the night.

That night, even though the chilly winter was biting into my toes, I was sweating. I tore off the patch and eventually by breakfast time I had found a friend in sleep.

I called for Nicorette gum and, some hours later, along with my dinner and more lists of urgent telephone messages that needed answering, I chewed on my first piece of Nicorette gum … yuk! Fuck this for a lark! I thought in temper. Is this what Charlie really had to endure? Probably not half or even a quarter of it … at least he didn’t have to chew on Nicorette gum! No doubt about it — Charlie certainly didn’t have it as bad as I had! I mean, he only had to endure beatings and the liquid cosh, while I had to endure cravings for nicotine! There I was, contemplating taking a hostage or two just so I could get my hands on a juicy Cuban cigar.

A change of clothing was to make me feel refreshed; I washed using a basin, no shower! Then again, Charlie gives himself a body wash up to three times a day; of course, he also does up to 6,000 press-ups, which generates a lot of sweat! I quickly dispensed with the idea of pumping out a quick 6,000 and found another method of keeping warm — running on the spot, lifting my legs high, and before long I was in a sweat.

I knew why I was doing this; I had an aim, I was not going to let it beat me. Everything was going great until I had a piece of sad news relayed by a note along with another list of ‘urgent’ telephone calls. Before long, I found it playing on my mind … all day! The sad news was starting to consume me; my isolation had helped to magnify and enlarge this piece of news until it consumed my whole fucking mind!

Teatime arrived and, somehow, I had to break the solitary conditions I was enduring in order to attend to a very urgent matter.

Charlie, however, in such circumstances wouldn’t be able to do this. He couldn’t say, ‘Hey, let me out for a few hours, I need to sort this problem out.’ I had learned a valuable lesson from all of this and it brought it home to me how Charlie must have felt when he received a piece of bad news and was powerless to do anything about it. If only Jack Straw or David Blunkett could be put into isolation, then they’d understand how and why prisoners kick off.

I thought to myself that I had failed: failed myself and failed Charlie. The problem was of a delicate nature and involved another party; it wasn’t my problem, but what if it was my problem, though? I could see how it would crack Charlie up if he wasn’t able to help his friends and family.

Maybe in some way it had been a blessing in disguise. I was starting to experience all of the chains and shackles of solitary life. Solitary wasn’t just about being locked in a room for 23 hours out of a 24-hour day. Solitary was about living with yourself, tolerating the things you couldn’t change, being able to accept things going wrong, anticipating things going wrong, hoping they didn’t go wrong!

That night, after being freed to solve the problem, I was back on the wooden shipping pallets, and for the first time in a week I was experiencing sound sleep. I made a point of stacking the pallets four high, leaving plenty of ground space to avoid the little creepy crawlies of the night! I’d read about an earwig lodging itself in Charlie’s ear — fuck that!

What the hell was I doing here? How long would it last? What was the aim of being in solitary … I really didn’t know. What has come out of it, though, is a greater understanding of what has caused Charlie to display such a violent temperament and how it came about.

Some of the things I came across in Charlie’s writing made for harrowing reading. How could I compete with what he was writing about? It became a challenge. I thought of the TV show Survivor, based on people being stranded on a desert island, the last one winning £1 million. Charlie would have won hands down. I mean, what torture the poor contestants must have suffered having to endure the agony of being stranded on a sun-kissed desert island and having to eat a fish’s eyeball. I think Charlie deserves £1 million for each year of his life spent in solitary conditions. The pain of being branded a lunatic and enduring the ravages of Broadmoor, Ashworth and Rampton special secure hospitals couldn’t be reinvented. I mean, what could I possibly do to get near to that? I just couldn’t get to grips with what he’d gone through.

I was starting to feel angry at how he had been caged up like an animal; I was starting to blame everyone but Charlie. I began to have violent thoughts, such as, The system’s a fucking joke, run by lunatics … I caught myself mid-thought, realising that it would be easy to become extremely violent when put in isolation — but what about after 24 years of it?

I continued enduring the mock solitary conditions. How long before I would crack? Is this what happened to Charlie? I didn’t have the disadvantage of people winding me up; I didn’t have malicious prison officers tormenting me or the humiliation of losing my privacy; I didn’t suffer the embarrassment of having to sit on my hands while someone shaved me; I was play-acting, trying to find the beast within me! I eventually started talking to myself, but didn’t dare answer! They say when you answer yourself, it’s the first sign of being mad. I wondered if Charlie talked to and then answered himself, but in another voice. I could see where he had got all of his ideas from and how they manifested themselves.

I would suggest to any writer that if you write about any subject then you would be advised to immerse yourself in your subject matter — fact or fiction. It doesn’t bring a better understanding, it brings oneness, and until you achieve that oneness you cannot impart the subject matter to the reader with the artistic input and authority it deserves.

The first cigar, after it all ended … brilliant, fan-fucking-tastic? No! The Havana Special tasted like an old sock! I endured the dried seaweed taste until, after a short while, the cool flavours the Cuban cigar imparted to me the thoughts of how the leaf had been gently rolled, traditionally, on the thigh of a virgin, which made me think about the ‘S’ word. I didn’t get much sleep that night! Charlie Bronson deserves a medal as big as a house, and I hope that what I have been able to do to his handwritten manuscripts is enhanced by my own experiences of solitary.

Stephen Richards