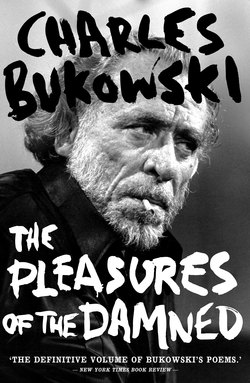

Читать книгу The Pleasures of the Damned - Charles Bukowski - Страница 27

На сайте Литреса книга снята с продажи.

Оглавлениеsomething for the touts, the nuns, the grocery clerks and you …

we have everything and we have nothing

and some men do it in churches

and some men do it by tearing butterflies

in half

and some men do it in Palm Springs

laying it into butterblondes

with Cadillac souls

Cadillacs and butterflies

nothing and everything,

the face melting down to the last puff

in a cellar in Corpus Christi.

there’s something for the touts, the nuns,

the grocery clerks and you …

something at 8 a.m., something in the library

something in the river,

everything and nothing.

in the slaughterhouse it comes running along

the ceiling on a hook, and you swing it—

one

two

three

and then you’ve got it, $200 worth of dead

meat, its bones against your bones

something and nothing.

it’s always early enough to die and

it’s always too late,

and the drill of blood in the basin white

it tells you nothing at all

and the gravediggers playing poker over

5 a.m. coffee, waiting for the grass

to dismiss the frost …

they tell you nothing at all.

we have everything and we have nothing—

days with glass edges and the impossible stink

of river moss—worse than shit;

checkerboard days of moves and countermoves,

fagged interest, with as much sense in defeat as

in victory; slow days like mules

humping it slagged and sullen and sun-glazed

up a road where a madman sits waiting among

blue jays and wrens netted in and sucked a flakey

gray.

good days too of wine and shouting, fights

in alleys, fat legs of women striving around

your bowels buried in moans,

the signs in bullrings like diamonds hollering

Mother Capri, violets coming out of the ground

telling you to forget the dead armies and the loves

that robbed you.

days when children say funny and brilliant things

like savages trying to send you a message through

their bodies while their bodies are still

alive enough to transmit and feel and run up

and down without locks and paychecks and

ideals and possessions and beetle-like

opinions.

days when you can cry all day long in

a green room with the door locked, days

when you can laugh at the breadman

because his legs are too long, days

of looking at hedges …

and nothing, and nothing. the days of

the bosses, yellow men

with bad breath and big feet, men

who look like frogs, hyenas, men who walk

as if melody had never been invented, men

who think it is intelligent to hire and fire and

profit, men with expensive wives they possess

like 60 acres of ground to be drilled

or shown off or to be walled away from

the incompetent, men who’d kill you

because they’re crazy and justify it because

it’s the law, men who stand in front of

windows 30 feet wide and see nothing,

men with luxury yachts who can sail around

the world and yet never get out of their vest

pockets, men like snails, men like eels, men

like slugs, and not as good …

and nothing. getting your last paycheck

at a harbor, at a factory, at a hospital, at an

aircraft plant, at a penny arcade, at a

barbershop, at a job you didn’t want

anyway.

income tax, sickness, servility, broken

arms, broken heads—all the stuffing

come out like an old pillow.

we have everything and we have nothing.

some do it well enough for a while and

then give way. fame gets them or disgust

or age or lack of proper diet or ink

across the eyes or children in college

or new cars or broken backs while skiing

in Switzerland or new politics or new wives

or just natural change and decay—

the man you knew yesterday hooking

for ten rounds or drinking for three days and

three nights by the Sawtooth mountains now

just something under a sheet or a cross

or a stone or under an easy delusion,

or packing a bible or a golf bag or a

briefcase: how they go, how they go!—all

the ones you thought would never go.

days like this. like your day today.

maybe the rain on the window trying to

get through to you. what do you see today?

what is it? where are you? the best

days are sometimes the first, sometimes

the middle and even sometimes the last.

the vacant lots are not bad, churches in

Eu rope on postcards are not bad. people in

wax museums frozen into their best sterility

are not bad, horrible but not bad. the

cannon, think of the cannon. and toast for

breakfast the coffee hot enough you

know your tongue is still there. three

geraniums outside a window, trying to be

red and trying to be pink and trying to be

geraniums. no wonder sometimes the women

cry, no wonder the mules don’t want

to go up the hill. are you in a hotel room

in Detroit looking for a cigarette? one more

good day. a little bit of it. and as

the nurses come out of the building after

their shift, having had enough, eight nurses

with different names and different places

to go—walking across the lawn, some of them

want cocoa and a paper, some of them want a

hot bath, some of them want a man, some

of them are hardly thinking at all. enough

and not enough. arcs and pilgrims, oranges,

gutters, ferns, antibodies, boxes of

tissue paper.

in the most decent sometimes sun

there is the softsmoke feeling from urns

and the canned sound of old battleplanes

and if you go inside and run your finger

along the window ledge you’ll find

dirt, maybe even earth.

and if you look out the window

there will be the day, and as you

get older you’ll keep looking

keep looking

sucking your tongue in a little

ah ah no no maybe

some do it naturally

some obscenely

everywhere.